Using SCAN: some quick examples

Yeah, right. ‘SCAN’. Yet another pretty acronym. What’s the point? What’s the use? Gimme some real examples, huh?

This one’s a follow-up to the previous post “Let’s do a quick SCAN on this”, in which I introduced the SCAN frame for sensemaking at business-speed:

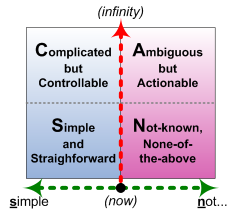

(The above is the updated core-graphic – see ‘SCAN – an Ambiguous correction‘.)

So: some real examples. Let’s get started.

Requirements definition

Let’s say we’re looking at requirements for a new IT-system, and we need to clarify the difference between ‘shall’ and ‘should’ in the requirements-specification.

As soon as we say it’s ‘new’, that tells us that there are unknowns. In SCAN terms, we start from Not-known. And we start pulling outward from Not-known, into the other spaces.

What is there that’s certain, that we know is Simple and straightforward? For example, what rules and regulations and standards must apply to this? In requirements terms, that’s mandatory: that’s going to be a ‘shall’. We can say that straight away: we don’t have to think about it.

What is there that, however Complicated it might be to do it, the system still has to deliver against that requirement? That’s probably going to be a ‘shall’ as well, because it’s over on the same side of the ‘controllable’ fence as the Simple. But we might have to spend a bit more time thinking about this.

What is there that’s a bit Ambiguous? – that we know is going to be a requirement of some kind, but it’s not particularly clear or definite as yet. That’s probably going to be a ‘should’ – desirable but not mandatory. But again, we might have to spend a bit more time thinking about it.

So we keep digging down into the ‘Not-known‘, pulling out requirement after requirement, stretching them out into one of the other three categories.

And note that there’s still uncertainty about both Complicated and Ambiguous: we’re going to have to spend more time on each requirements-item there, to determine whether they really are a ‘shall’ or a ‘should’.

Yet to quote a great comment by Cynthia Kurtz on the previous post:

Give me ten years and I can work my way into making just about anything work (if it doesn’t kill me first). Give me ten minutes and it had better be simple.

So if we don’t have the time to explore further, we treat each item just as they are: Complicated gets squeezed down into the enforced ‘shall’ of Simple, and Ambiguous gently drops back into the acceptance of a less-enforceable ‘should’, where it may still remain somewhat ‘Not-known’ right up until the last moment.

That’s how Agile-style requirements-processes work: just before the start of the sprint (or whatever the development-cycle is called), we compress everything down to Simple, or Not-until-next-iteration. At the end of the cycle, we allow ourselves the time to re-assess what we’ve done, and re-explore the requirements-space for items that we could do in the next cycle. We push the time-box back-and-forth: stretch to review the Complicated and the Ambiguous, the ‘shall’ and the ‘should’; pull some of the ambiguities across to ‘what we we think we can do’; and then compress it back down again to get the work done in the available time.

EA reference-framework

Reference-frameworks are a commonly-used tool for governance in enterprise-architectures. In effect, they’re another type of requirements-specification, but one that straddles across a whole suite of projects, programmes or portfolios, and often aim to apply for several years across the whole of that space. It’s a tool to manage risk, opportunity and cost over the longer term.

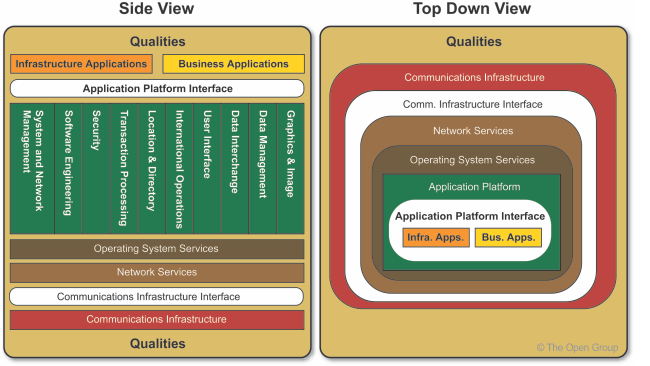

TOGAF TRM Orientation Views ((c) The Open Group)

TOGAF TRM Orientation Views ((c) The Open Group)

(The example above is the raw ‘unpopulated’ shell for the TOGAF 9 ‘Technical Reference Model’. For real-world use, specific technologies would be defined for each of the cells in this framework, as the standard reference-framework for the organisation’s IT technology-architecture.)

A reference-framework is typically used to specify particular technologies for use in particular contexts, in IT and beyond. As with the requirements, there’s a balance between ‘shall’ and ‘should’ and the real-world: the reference-framework says what we want to happen, the real-world tells us what we have, and there’s then the governance-negotiation that goes on between the two. Hence TOGAF Phase G, for example, and the delicate diplomacy needed around architecture-dispensations or waivers and the like. We then also use the reference-framework later on, when reviewing previous dispensations, to see what we should have done ‘in a perfect world’, and explore possibilities to bring whatever-it-is back into line with the intended architecture.

The catch is that most reference-frameworks take a Simple view: everything is portrayed as an ‘is-a’, a ‘shall’, a ‘must-be’. Which tends to bring on a lot of fights, and denigration about ‘the dreaded architecture-police’, because the real-world just isn’t that simple… And this tension is only going to get worse as the business-space becomes further fragmented with outsourcing, cloud, ‘bring-your-own-technology’ and more. We need a better, more flexible way to define and use reference-frameworks.

To reduce the fights, we can use a SCAN to help us identify where we must stand our ground, architecturally speaking, and where it’s safe to back off and let people ‘do their own thing’.

That time-axis in SCAN is important. If we know we don’t have time, we’re forced into a straightforward split between the Simple – what we know we can do, what we know we can support – and the ‘Not-known’ – otherwise described as either “you ain’t havin’ it” or “you’re on your own, bud, we ain’t touchin’ it”. Which, yes, sometimes that’s the only choice we have. And in that case, the reference-framework would describe what’s supported, and what isn’t: which also means that there needs to be the governance to support those constraints in real-world practice – and the clout to back it up without brooking any argument.

Yet most real-world contexts demand a bit more flexibility – which also means that we need the time to support that flexibility, and the governance to support that flexibility, too. Given that stretching of time, we can give a somewhat more sophisticated assessment that covers the full SCAN.

In effect, we extend the simple ‘true/false’ – it is or it isn’t, ‘we can’ versus ‘we can’t’ – to a more modal logic of possibility and necessity:

- is-a (Simple) – “we’re a Microsoft house” (that’s what we do, so don’t expect it to be cheap or certain or even doable with anything else)

- is-sometimes-a (Complicated) – “we prefer Windows, and we do that best, but we can also support Microsoft packages on Mac, UNIX and Red-Hat Linux” (it’ll cost extra time and money, but we know it’ll work)

- is-believed-to-work (Ambiguous) – “there are [these listed] equivalent packages on Windows and on [these listed] other operating-systems: we’ve been told they work, but we haven’t yet tested them ourselves” (and if you want us to test them, it’ll cost both time and money, and may not work anyway)

- none-of-the-above (Not-known)- “sure there’s plenty else out there, but we don’t know much of anything about it” (we have no idea what it’ll cost even to find out more about it, and no idea if it’ll work at all with what we have)

A practical catch here is that most current EA toolsets don’t support this kind of modal-logic in reference-frameworks (or anything else, for that matter). Usually the nearest we have for this are composition- or aggregation-relationships: they’re sort-of-usable as a workaround for this, but they’re not quite the same, and can be misleading if we’re not careful.

Anyway, much the same happens with reference-frameworks as in Agile-development: over time, there’s a steady migration of some (but not all) from Complicated to Simple, and some (but not all) Ambiguous to Complicated. Yet some will always remain Complicated; some will always remain Ambiguous; and even more, there will always be some that’s Not-known. A repeated, recursive SCAN helps to clarify what will move between those ‘domains’, and when.

Leave a Reply