Money, price and value in enterprise-architecture

To my mind, the way that most people seem to handle the relationships between money, price and value in enterprise-architecture and EA models is, frankly, an utter shambles. So let’s get a few things straight here:

- there are many other forms of value besides money

- in most aspects of enterprise-architecture, money is not the form of value that matters

- in many ways, this applies more to commercial organisations than to non-commercial ones

Yep: a lot of people are going to be pretty upset about those statements above – or, at the very least, would dismiss me as some kind of wildly-idealistic nutcase.

But they’d be wrong – dangerously wrong. So dangerously wrong, in fact, that they’re at real risk of developing architectures that will guarantee the failure of their respective businesses.

To be more precise, the core problem, and risk, is that if we over-focus on money, we destroy the real value – and thence usually the money as well. Not a good idea…

Yet since so many people do get this wrong, it’s something that really does need a solid explanation. So let’s go to it, yes?

For simplicity, I’ll use the core theme of Enterprise Canvas, that everything is or represents a service. This’ll allow us to describe things in a consistent way – if also somewhat abstract, so I’ll pepper the explanation with real-world examples where I can. Be warned, though, that this is gonna be a long one…

Organisation and enterprise

A couple of fundamentals first. When I talk about ‘enterprise-architecture’ here, I mean two distinct things:

- this is the architecture of the enterprise as a whole, not solely the enterprise-IT

- we develop an architecture for an organisation, about its enterprise

The crucial point here is that ‘organisation’ and ‘enterprise’ are not the same:

- the enterprise is a social structure, primarily emotive/aspirational in nature

— defined by vision, values and mutual commitments

— the enterprise is – it provides motivation, ‘why?‘ - the organisation is a legal structure, primarily conceptual/physical in nature

— defined by rules, roles and responsibilities

— the organisation does – it provides action, ‘how?‘

In essence, the enterprise is just an emotive idea – for example, the TED vision of ‘ideas worth spreading’. And in practice, an organisation will position itself in relation to an enterprise (or, in some contexts, any number of enterprises – though it’s simpler to understand in the single case).

An enterprise or an organisation can take on any scope, and some cases their scopes can coincide – in other words, where the organisation ‘is’ the enterprise. For most enterprise-architecture purposes, though, the scope-relationship we need is where the respective enterprise is some three steps larger than the scope of the organisation itself: first, the organisation’s supply-chain or direct value-network; then its overall market; and outward again to the broader social context in which that market exists.

In terms of mainstream economics, a commercial organisation needs to ‘make money’ in order to operate, and continue to operate, within its market. Yet the market and, in turn, the organisation, will operate in the context of the overall enterprise – and the enterprise determines what ‘value’ is within that context.

For example, the TED organisation ‘makes money’ by running conferences on the theme of ‘ideas worth spreading’. Yet although the TED organisation promotes specific ideas in its conferences, it is the overall shared-enterprise that determines whether those ideas are indeed worth spreading – and, hence, via a somewhat roundabout route, whether TED’s conferences are worth paying for. For a commercial organisation, no perceived-value ultimately equals no money: which is kinda important, yes?

To understand where the money comes from – and, equally, where it goes – we first need to understand value. For the business-aspects of an enterprise-architecture, money may well be where we want to end up: but it’s not where we start. Instead, always, we must start with value.

Value and values

In Enterprise Canvas, everything is described in terms of services. (In that sense, ‘products’ are actually ‘proto-services’ that enable self-delivery of some kind of service.)

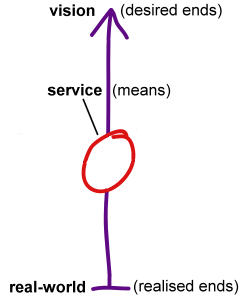

As the term suggests, each service serves. And ultimately what it serves is the aim or vision or ‘desired ends’ of the respective enterprise – for example, ‘the dissemination of ideas that are worth spreading’. Every service in the enterprise contributes in some way towards that overall aim. (If it doesn’t contribute towards that aim, it shouldn’t be there…) Every service is a means via which some aspect of the ends of the enterprise may be achieved.

And since the organisation exists within the context of an enterprise, every service within the organisation, by definition, would or should also contribute towards those desired-ends. The organisation itself is a means to achieve the enterprise’s aims.

Remember that the enterprise – and, more specifically, the enterprise-vision – will determine what value is within the context. This is usually expressed as values (plural, rather than singular) – for example, what determines ‘worth’, within that vision of ‘ideas worth spreading’. In turn, the values are usually expressed in more actionable form as rules and principles – guides to ensure alignment to the overall vision in sensemaking and decision-making, in design and in real-time action.

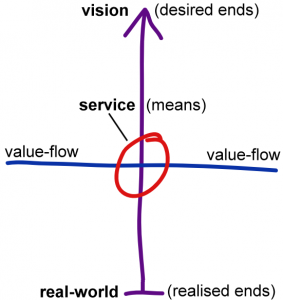

Most enterprises that we’d notice in real-world practice are social – in other words, not an ‘ends’ that an individual can achieve on their own. Organisations develop to coordinate people’s actions – services – towards the ‘ends’ of a shared-enterprise. And different people, and different organisations, tend to focus on different aspects of how to reach towards those ends – which is how and why we have transactions and interactions between services. So services serve and enact the values of the overall vision, and, usually, exchange various forms of value with other services. In Enterprise Canvas, we depict this as a vertical connection with enterprise-values, and a horizontal flow of value around the services of the enterprise.

Each service makes an offer – a value-proposition – which establishes what the service can provide that would be perceived as ‘of value’, in relation to the values of the enterprise. It’s that connection to enterprise-vision and enterprise-values, in fact, that makes the value-proposition ‘of value’ in the first place.

So an enterprise consists of all manner of services, each with their own value-propositions within the terms of the enterprise, all exchanging value in all manner of roles as ‘service-providers’ and ‘service-consumers’. Which, in turn, gives us the notion of the ‘supply-chain’:

And, also, the market, within which all of the more visible transactions take place, and which itself provides the rules and governance for those transactions.

But remember that all of this takes place within the broader context of the shared-enterprise. Which determines what ‘value’ is, for all the players in that enterprise and market.

So how does ‘price’ come into the picture? That’s where things get a bit more tricky… and where a lot of people in enterprise-architecture – and, especially, the business-architecture domains within EA – will often get it badly wrong.

Price and value

Most conventional business-models focus only on transactions, and on the monetary costs and monetary returns of those transactions.

What we term ‘price’ is actually a somewhat-arbitrary translation – a valuation – of the perceived-value of something, usually into the terms of a ‘fiat-currency‘ that provides a nominally-standardised means to exchange purported ‘rights’ to valued resources. (Interestingly, fiat-currency often also confers supposed ‘rights’ to not have to deal with items of ‘anti-value’, such as waste, pollution or uncomfortable or dangerous living-conditions. For enterprise-architectures – especially on a larger scale – there are often some huge unacknowledged and unaddressed issues there… but that’s another story for another time, I guess?)

Pricing dominates most views of business; there’s even an entire academic discipline – microeconomics – that revolves around concepts of pricing. Yet pricing is always a complex, non-linear transform – and most of those transforms are non-reversible, too, which means we usually can’t use money itself to define or even determine the totality of perceived-value. And all of this discussion of pricing is actually always, and only, about one specific approach to understanding value: there are many others – most of which don’t suffer from the surprisingly narrow constraints of what types of value can be described in monetary terms…

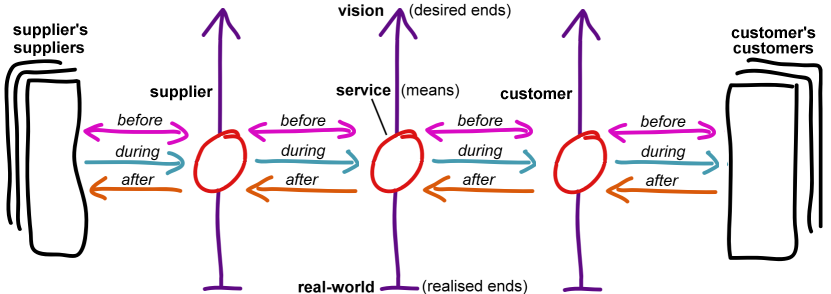

In reality, the transactional focus for most pricing, and most ‘valuation’, encompasses only a small part of what I often describe as the ‘market cycle’:

If we focus only on transactions, the money may well flow well, for a while: but if we do so, the market-cycle will eventually break, and with it the real connection to value – which in turn breaks the connection to value-flow, and thence to money. In short, losing the link to value equals losing any link to money. Which is a kinda important concern for a business-architecture?

If we map the market-cycle in terms of value-flow between services, we can split this architecturally in terms of what needs to happen before, during and after the nominal transactions between services:

Long before any transaction happens, there are all manner of other interactions between the service and other players in the shared-enterprise. For example, some of the first questions revolve around trust, or reputation as a kind of proxy for trust: the service makes its value-proposition promise, but will anyone trust in its ability – or intent – to deliver on that promise? And if it’s trusted to deliver at all, to what extent will it actually deliver? The organisation will need to acknowledge and find ways to resolve those uncertainties – not least because they have a deep impact on perceived-value, and hence the relation between between perceived-value and price relative to the organisation’s business-competitors.

Next, there are a whole stream of interactions around relationship-building. In service-provision, people connect to the enterprise-vision through the agency of the organisation and its services – and without that sense of relationship, there’d be little perceived reason to connect with the organisation itself. No relationship means no connection to value means no reason-to-transact means no transaction means no possibility of profit: it’s startling how few ‘marketers’ manage to connect all of the links in that chain…

Only once relationship and trust is there some possibility of conversation. And it’s in conversation that all the conditions and trade-offs of a potential transaction are worked out: in particular, the complex partly-rational, partly-emotional weighting and assessment through which perceived-value is derived, and thence, in a money-based transaction, the comparison between perceived-value and price. Or, more precisely, not just monetary price, but cost in every form of value relevant within the enterprise – another point that too many ‘marketers’ miss…

All of that happens before the transaction.

During the transaction – delivering on the service-offer, the value-proposition – there’ll usually be plenty of subsidiary interactions (is this the item specified? does it match the description? is it delivered ‘on time and on budget’, in appropriate condition?), all of which are extremely important in the detail of service-delivery, or product-delivery. But we can gloss over most of that for our purposes here. One key point, though, is that unless the the service-offer is about money itself, money isn’t much involved at this point: it’s still in the somewhat mythical realm of ‘price’.

It’s only after the transaction – and then usually only in a commercial context – that money comes directly into the picture. In a commercial context, the transaction isn’t complete until we’ve been paid… But again, it’s only one form of value, one form of cost – and there can well be many others, as per the enterprise vision and values.

The value-proposition, and the interactions that establish value, take place before the transaction. Perceived-valued is delivered during the transaction. And after the transaction, some aspects of value may be returned in some variant of monetary form. So money comes properly into the enterprise picture only very late in the game, after all of the business-critical activities – the actionable, changeable, designable activities – have already happened. In other words, if we focus only on money, we block the view to all of the things that make that money happen. Again, not a good idea…

Price is one specific view of the relationship between perceived-value and money; and in a money-based possession-economy – the kind of economic-model that most of us live in at present – money is the interchangeable token for access to items-of-value. In practice, and in business, we’ll usually see revenues and costs described solely in monetary terms. Yet other than in certain special-cases, money is not value itself: it’s only a proxy for value. And failure to grasp that perhaps-subtle yet extremely-important distinction leads to all manner of problems, in enterprise-architectures and elsewhere.

For many people in business, ‘making money’ may well be seen as the reason for doing the business. But other than in certain special cases, ‘making money’ is not what the enterprise is about – and the organisation does its business only in the context of that enterprise. So if, to use the TED example, the focus of the enterprise is ‘ideas worth spreading’, and the organisation is focussed only on ‘making money’, it’d literally not be in the same enterprise – and hence not likely to make much money.

In short, for a commercial organisation, the way to make money is to keep the focus on the shared-values of the enterprise – not on the money. Paradoxically, the way to make money is to focus on everything other than the money: we need to keep attention on the whole of the market-cycle, rather than solely on the ‘money-making’ transactions in that cycle. Which some business-folks do get: see Hagel Brown and Davison’s The Power of Pull, for example, or Tony Hsieh’s Delivering Happiness. But as yet most still don’t seem to get it – hence, for example, the old adage that “a fool knows the price of everything, but the value of nothing”. And then wonder why their businesses don’t work…

So for enterprise-architects and business-architects, the implication should be obvious: don’t allow price or money to distract us from value – because value, not money, is what underpins the entire enterprise.

Yet there’s also another, and often much more forceful, source of distraction: the investors. As enterprise-architects, we need to find some means to deal with this distraction if we’re ever to find our way out of the architectural ‘money-mess’.

Money, investment and ‘owners’

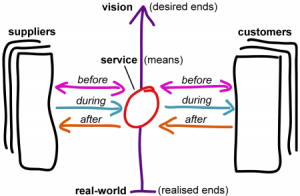

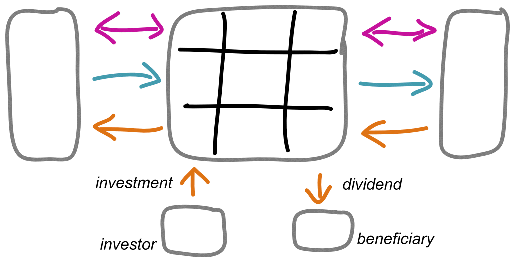

In a sense, investors are just another kind of service-provider, or, in the returns to investors as beneficiaries, just another kind of service-consumer. Yet in Enterprise Canvas, we’re careful to model them in roles that are separate and distinct from those of the mainstream providers and consumers:

One reason we model this differently is that value-flows from investors and to beneficiaries tend to go the opposite direction to those of their provider or consumer counterparts: the types of values provided or delivered – such as money – are those that tend to arise only in the backchannel, or what are usually the ‘after’-transaction flows, rather than those in the main transactions. For example, an investor provides money to a startup so that service-providers can be paid whilst saleable products or services are developed; and once products or services are sold, some of the revenue is diverted back to the investors as ‘beneficiaries’.

But there are several very important complications here – especially where there’s an over-focus on money, and even more so where financial-investors alone are described as ‘the owners’.

The first complication is that, in reality, there are many types of investors, who invest many types of value. For example, the parents may well support the young members of a startup, in many forms such as workspace, utilities, food and lodging, social-connections, business-credibility, credit-guarantees and much more: money is often part of the value-picture there, though rarely the only one. A community supports employment in its midst, providing the social fabric within which enterprises and organisations can do business. Once we take a true whole-of-enterprise view, it’s a much richer, much more complex picture than the ludicrously-limited money-only view – and we need that rich a view in order to make sense of what’s actually going on.

The next complication is that where investors do expect returns from their investment – which not all investors do – the forms of value in which they expect the returns may not be the same forms of value that they’d invested. For example, parents may invest money in that startup, but hope for returns more in the sense of familial satisfaction; a community invests space and social-sanction, but expect returns in the form of stability, certainty and social-support. Even where the investment has primarily a monetary focus, the return may not be directly monetary as such: for example, Apple has never yet paid a dividend on any of its public shares. Getting the balance right between all of these interchanges can be tricky indeed…

And that complication can be made a lot more difficult if we make the mistake of thinking that money is the only valid form of value. The classic example is where although the community and others may invest vast amounts of non-monetary value into an organisation’s business, the organisation focusses on converting as much value as possible to monetary form, to the financial-investors – who are then the only ones to whom the benefits are directed. In short, whether by intention or not, the organisation there acts as an institutionalised form of theft from the non-monetary investors. The result is that whilst the organisation may, for some while, seem highly profitable to the financial investors, at some point it will suddenly lose its societal ‘licence to operate‘ (to use business-commentator Charles Handy’s term) – and the profits will vanish overnight, to be replaced by a lot of social anger. Architecturally, this is a known anti-pattern that all but guarantees business-failure: it’s not a good idea to allow this mistake into our enterprise-architectures.

But perhaps the most serious complication, and the key reason why we model these relationships differently in Enterprise Canvas, is that, in effect, we have two fundamentally different types of investor/beneficiaries:

- those who invest as part of their commitment to the same enterprise – for example, they invest in the TED organisation because of their own belief in the importance of ‘ideas worth spreading’

- those who are not committed to the enterprise and its values, but seek returns in forms of value other than those of the enterprise – for example, someone who invests in the TED organisation solely for the expected financial-return, or for a ‘job’ or suchlike

(An individual investor may take both roles, of course, but it’s simpler to treat them separately here.)

For the first type, where the investment aligns with the enterprise, it’s essentially the same type of value-flow as in the main transactions: the main reason to model these relationships differently is that the value-flows go ‘backwards’, as described above.

For the second type, there is a huge danger of distraction. Their investment may be necessary, but their own focus is on a different enterprise – for example, ‘making money’, or making money for some other purpose entirely, rather than the TED enterprise of ‘ideas worth spreading’. If we allow these investors to distract us into paying too much attention the demands of their chosen enterprise, they will force us to lose focus on the enterprise that our organisation actually does it business in. Which, as we’ve seen above, is a guaranteed recipe for business failure.

And all of this is made a lot harder by the social-myth of financial-investors as ‘owners’ of the organisation, because, by custom, and often by law, their views supposedly take priority everyone else. If their enterprise does not align with the enterprise of the organisation (and for money-oriented investors via the stock-exchange or suchlike, it usually doesn’t), there’s then a very high risk that their enterprise will take priority over the actual enterprise of the organisation – leading directly to all of the problems described above. We’re also likely to see ‘owner’-investors installing executives who align with their enterprise, rather than the actual enterprise of the organisation: which, if their enterprise is ‘it’s all about making money for me’, means that those executives are likely to focus primarily on their own benefit, above all else – with the kind of disastrous results that we’ve seen for too many large businesses over the past few years.

(This isn’t just a modern problem, of course: the collapse of railway-investment bubble of the late 19th century is immortalised in the ironic remark in Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark that “they threatened its life with a railway share”…)

In short, paradoxically, the best way to make money for financial investors is to ignore the demands of the financial investors, and keep the focus of the organisation on the enterprise-values instead. Which, when those investors are deemed to be ‘the owners’ of the organisation, is definitely tricky… but that’s the kind of challenge we must face as enterprise-architects and business-architects whenever we deal with money, price and value in enterprise-architecture.

—

Many thanks to Pat Ferdinandi (@thoughttrans) for suggesting the topic for this post, in her comments to my previous post ‘The LEARN principle‘.

Leave a Reply