Yet more on ‘No jobs for generalists’ [3c]

Why is it so hard for enterprise-architects and other generalists to get employment as generalists – despite the evident very real need for such skills in the workplace? And what part do current business-paradigms play in this problem?

[[This post has been split into six parts, in line with the chapter-headings:

- Part 3a: ‘An incomplete science’ – about Taylorist notions of ‘scientific management’

- Part 3b: ‘Management as a service’ – a service-oriented view of the role of management

- Part 3c: The impact of the ‘owners’ ‘ – about how and where financial-investors come into the picture

- Part 3d: ‘A question of fitness’ – exploring the use of ‘fitness landscapes’ to guide selection of appropriate architectures

- Part 3e: ‘A question of value’ – how we could describe the business-value of generalists

- Part 3f: ‘No jobs for generalists?’ – a brief(ish) summary of the whole series

Previous: Part 3a: ‘Management as a service‘]]

The impact of the ‘owners’

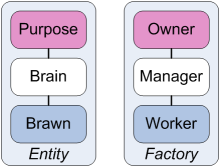

If we follow the Taylorist logic of organisation-as-machine, then not only does the mindless machine require a controller-manager to control it, but it also needs an owner to give that control its direction and purpose.

In the commercial context, the organisation is not just a machine, but a machine-for-making-money. That, we’re often told, is the sole purpose of any business.

Yet architecturally this makes very little sense: from what we know of the psychology of motivation and suchlike, money itself is one of the least-successful and least-reliable motivators for enterprise. (Interestingly, the motivators that do work well – autonomy, mastery, and purpose – are all explicitly blocked in Taylorism: autonomy is forbidden, skill (mastery) is designed-out wherever practicable, and purpose comes solely from the outside.) However, most current law and custom assumes that the financial-investors in an organisation are the ‘owners’ of that organisation, and thus have exclusive right to set the direction and purpose for that organisation. The owners are the controllers of the controllers.

[This is often viewed as a kind of feudal structure, but in fact it doesn’t even manage that. Feudalism is a hierarchy of Other-as-subject, and ultimately relies on two-way relationships of responsibility – as expressed in feudal concepts such as noblesse oblige. By contrast, the ‘possessionist’ ownership-model is a hierarchy of Other-as-object, where ‘lower’ has responsibility to ‘higher’, but not the other way round – as expressed in concepts such as the limited-liability corporation, and, in terms of responsibility-failure, the prioritisation of insubordination over insuperordination. In psychological terms, feudalism all too often devolves to a co-dependent ‘racket’ of mutual Other-blame; but the Taylorist-style ‘ownership’-model all too easily devolves to systematic life-theft – in effect forcing ‘inferiors’ to enslave themselves on behalf their supposed ‘superiors’. In terms of architecture – let alone ethics – it’s a really bad model, in fact almost the worst possible system we could devise – but we need to remember that it is the one we’re stuck with at present, and we need to architect with that reality in mind…]

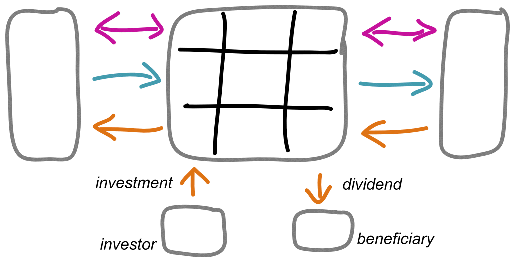

The predominant concept of ‘the market’ – as typified by the various stock-exchanges, and as regulated in corporate law and the like – assumes that all financial investors are the same. Anyone who invests money in a company – either directly, or indirectly via stocks and shares – is an ‘owner’ of that company, and hence has rights both to the financial returns from that company’s activities, and to the control of how that company attains those financial-returns. In Enterprise Canvas, though, we’re careful to separate out two distinct roles – Investor and Beneficiary – and the respective relationships of ‘investment’, from the Investor role, and ‘dividend’, to the Beneficiary role:

That separation of roles in Enterprise Canvas enables us to identify some key distinctions between at least five different types of financial-investors, each with their own fundamentally-different motivations for investment:

- symbiote (primary-investor) – committed to the aims of the enterprise

- parasite (beneficiary-investor) – interested primarily or solely in returns to self

- grazer (market-investor) – invests in the market, not the organisation

- predator (attack-investor) – invests for the purpose of gains from destruction

- scavenger (derivative-investor) – invests solely to ‘game’ disruption within the market

The symbiote is the only type of financial-investor who is committed to the enterprise itself. As a true risk-sharing investor, the support will usually be maintained ‘though thick and thin’ – through good-times and bad-times – and usually over the longer term. In essence, the financial investment is primarily to support the aims of the enterprise: there is a probable desire for financial-returns, but that’s often secondary to the focus on support. In Enterprise Canvas, the focus here is on the Investor role and and ‘invests’ relationship.

The parasite is similar in some ways to the symbiote, but the emphasis is more on what can be obtained from the organisation, rather than on what the enterprise itself might need. In Enterprise Canvas, the focus here is on the Beneficiary role and the ‘dividend’ relationship. To use a natural-world metaphor, it’s a leech, or tick – a parasite attached to its host. Pension-funds are probably the archetypal parasites in this sense: like the symbiote, the parasite will usually maintain its support over the longer-term, but in return will demand stability and predictability, and active minimisation of what it sees as any risks to its investment.

The grazer is another form of parasite, but one stage further removed: it has little to no interest in the underlying enterprise of the organisation, and its interest in the organisation is solely in in terms of what of value can be abstracted from it in the short-term, after which the grazer will move on. In effect, it’s a low-level predator, for which probably the natural-world metaphor is the vampire-bat – a self-mobile bloodsucker. In the business context, the grazer’s assertion of ‘anti-responsibility‘ towards its host is probably best typified by a financial-commentator’s response to the March 2011 Japanese tsunami, as reported by the lifestyle-magazine Vanity Fair:

In these tough economic times, isn’t it nice to know that calamitous natural disasters needn’t have an adverse affect on your investment portfolio? After the 8.9-magnitude earthquake in Japan failed to induce a market nosedive, CNBC’s Larry Kudlow expressed his relief in terms that seemed to appall even his fellow cheerleaders for capitalism: “The human toll here,” he declared, “looks to be much worse than the economic toll and we can be grateful for that.”

The predator takes this a step further, using some form of financial-investment to take control of the ownership of an organisation, and then tear it apart solely for personal gain, through often-illegal activities such as asset-stripping and ‘phoenixing’. The typical natural-world metaphor for this is the hyaena: a pack-hunter, pooling resources to take down larger but weaker prey. The enterprise of the organisation, or its viability beyond the immediate moment, are of no interest whatsoever to the predator.

The scavenger is a secondary predator that applies very little investment of its own, but relies on predators and other ‘market-forces’ to provide it with sources for financial-returns. The natural-world metaphor here is the vulture:

Vultures seldom attack healthy animals, but may kill the wounded or sick. When a carcass has too thick a hide for its beak to open, it waits for a larger scavenger to eat first.

Scavenger-investors thrive on disruption and instability – “vast numbers [of vultures] have been seen upon battlefields”, to quote Wikipedia – and will typically seek to create it via leverage of at-a-distance mechanisms such as derivatives-markets. As with the active predator, there is no actual interest in the enterprise of the organisation itself, but, like a parasite, may have some interest in the organisation’s viability, in order to maintain the ‘game’ for as long as possible. Financial-investment in the organisation is solely for the purpose of creating or leveraging price/value mismatch and other forms of instability, through mechanisms such as short-selling; the investment is typically very short-term – sometimes as little as milliseconds or less – and in certain cases, such as in naked short-selling, may not exist in fact at all.

As in a large-scale natural ecosystem, scavengers, predators, grazers and parasites do all have their part to play within the Schumpeterian ‘creative destruction‘ of the overall business-market. But from the perspective of the individual organisation within the shared-enterprise of that market, any type of investor other than a symbiote is likely to be bad news.

And since as enterprise-architects we’re employed by and on behalf of the organisation – not the market – then the needs of the organisation must come first. Which means that any structures we develop must prioritise and support the symbiote-investor relationship above all other types of investor. Which leads to a self-evident need for architectures – and in turn, recruitment-models – that support the needs of the symbiote-investor: resilient, responsive, self-adaptable, able to keep on track to purpose over the longer-term, and with good financial and other returns. And, if possible, predictable enough to keep the parasite-investors happy too.

Yet that’s exactly what Taylorism and similar linear-paradigm models do not give us. What they do give us, as we’ve seen above, is brittle, non-responsive, slow-to-change purposeless ‘machines’, inherently prone to failure-cycles caused by short-term and a built-in inability to ‘connect the dots’.

In short, not good for anyone in the enterprise, or any of its direct investors. But it is good for the grazers, because it does give good results in the short-term – for a short while, anyway. It is good for the predators, because it leaves so many organisations much weaker and less able to defend themselves than they would otherwise be. And it is good for the scavengers, because the lack of resilience leaves it wide open to the the kinds of disruption on which the scavengers thrive.

The reality is that much of what we have at present – in Taylorism, in the management-models that derive from it, and in the market-structures and corporate law – these current mechanisms prioritise the needs of the respective investor-types in the exact opposite order to what our organisations need: scavengers come first, symbiotes come last. Which is not wise from anyone’s perspective: in an ecosystem that’s that far out of balance, the predators become so ‘successful’ that in killing off all of the prey, they kill off themselves as well. The scavengers would last a little while longer, of course, but when there’s nothing left, they even they will die too. Eventually…

Not a good idea, really. Yet it is what we have – and hence it is what we have to design around. In our architectures, we can’t do anything about the politics or the law (other than keep documenting how and why it doesn’t work). We can’t do much about management-structures (other than keep documenting how and why they don’t work, too). We probably can’t do much about the linear-paradigm (other than describing its inherent flaws, and challenging its various manifestations such as IT-centric ‘process-reengineering’ and the like). What we can do, though, is make it clear why and where our architectures need their generalists – and help others describe what it is that those generalists need to do, so that our organisations’ recruiters can find the people that we need for those roles.

That’s what all of this long series of posts has been about: finding the right people to fit a very real yet all-too-often unacknowledged business-need. Market-misdesigns, management mis-structures, and Taylorism’s misunderstanding of ‘scientific management’, have all played their own significant parts in this mis-fit to business needs, as we’ve seen. Somehow we need to find a better fit, for everyone.

Yet behind that is the whole question of ‘fitness for purpose’: what do we mean by ‘fitness’ anyway?

[[Next: Part 3d: ‘A question of fitness’]]

You might also want to look at “The Economy of Discourses: a third order cybernetics?” by Vincent Kenny & Philip Boxer

http://www.oikos.org/discourses.htm

Richard – Many thanks for the pointer to ‘Economy of Discourses’ – duly bookmarked! 🙂