Requisite-fuzziness

How should we respond to inherent-uncertainty in qualitative-requirements, for enterprise-architecture and the like? Yes, we can reduce every qualitative-requirement to some sort of metric, but is that always a wise thing to do? And if not, how can we tell whether it is or isn’t an appropriate answer? – and what to do if it isn’t?

This is a follow-on to the previous post, about ‘Metrics for qualitative requirements‘, and in response to some of the issues that came up in the comments there.

What I’m looking for, I guess, is a different kind of metric that (in homage to Ashby’s ‘Requisite Variety‘ and Ivo Velitchkov‘s concept of ‘Requisite Inefficiency‘) I’d probably describe as requisite-fuzziness.

It’s sort-of related to probability, or uncertainty, but it’s not quite the same: more an indicator of how much we need to take that uncertainty into account in system-designs and system-governance. If there’s low requisite-fuzziness in the context, we can use simple metrics and true/false rules to guide decision-making for that context; but if there’s high requisite-fuzziness, any metrics must be interpreted solely as guidance, not as mandatory ‘rules’.

(Note also that ‘fuzziness’ and requisite-fuzziness is dependent in part on the ‘variety-weather’ or variety of the variety itself in each context – see the post ‘Requisite-variety and stormy weather‘.)

Requisite-fuzziness thus describes and determines the amount of leeway and allowance-for-uncertainty that must be built into the system – and hence also the extent of requirements for ‘manual override’ for automated systems that are only able to follow ‘the rules’. One of the huge challenges for real-world system-design is that computer-based IT and other automation tends to have a very low natural-tolerance for ‘fuzziness’ – far lower than the requisite-fuzziness in that context: hence whenever we get IT-centrism, or any other variant of people becoming over-enamoured with ‘deus-ex-machina’ technology-based ‘solutions’, we’re likely to get serious failures around inability to cope with requisite-fuzziness.

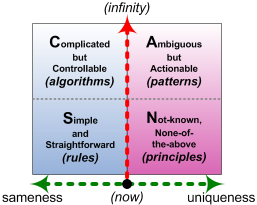

From an enterprise-architecture perspective it’s probably easiest to describe this in terms of the SCAN framework. But first, let’s illustrate this with a more concrete and prosaic example of a quantitative-metric applied ‘as’ a qualitative-requirement: speed-limits.

The purpose of speed-limits is to provide a meaningful and useful guideline to support safe driving and safe road-use. All fair enough. And the provision of an identifiable measure of ‘probable safe speed’ does help in this – but not if the metric itself is used as a substitute for personal-judgement and personal-responsibility for safe driving. Which happens a lot…

To illustrate the point, here’s a real example where predefined speed-limits make almost no sense:

It’s on a twisting narrow country lane, weaving its way around steep banks and deep gravel-pits, often very slippery in the wet, and almost no place to pass: definitely not a place to drive fast. And frankly, given that that road is also popular with dog-walkers and weekend-cyclists, it’s unsafe for a car at almost anything above a slow walking-pace…

The ’30mph’ limit-sign is what’s known as a ‘repeater’, indicating the continuation of a speed-limit – in this case because it’s quite a way out of the village, where the usual relaxation of the speed-limit would apply. Yet many people would take the 30-limit there as a permitted or even recommended speed – which, legally, they’re permitted to do, despite the ’20mph’ advisory-sign above. In other words, the metric is less of a help than a hindrance in encouraging safe-driving in often highly-variable conditions: it doesn’t adequately describe or support the requisite fuzziness of measure for the variability of the context.

The reality is that whilst vehicle-speed can be measured quite easily, often to a high degree of precision, ‘safe speed’ is highly-variable and highly-contextual. For example:

- road-conditions – dry, wet, icy, gravel-strewn etc

- condition of the vehicle – brakes, tyres, quality or reliability of controls etc

- state of the driver – mental state, emotional state, medical conditions, affected by digestion-in-progress etc

- awareness of the driver – hazard-awareness, familiarity with the vehicle (e.g. rental-car), distraction (phone, radio, sat-nav, children fighting in the back…)

- competence and experience of the driver – years of driving, familiarity with the locale etc

- interactions with other drivers – too slow, too fast, tailgating, lane-jumping, horns blaring, emergency-vehicles pushing through

- condition of other drivers’ vehicles – brakes, tyres, acceleration etc

- interactions with other road-users – cyclists, pedestrians, motorcyclists, schoolchildren, crowds

Yet when the speed-limit is interpreted as an absolute-proxy for ‘safe-speed’, we get all manner of behaviours that are definitely not safe at all:

- drivers claiming that they have a ‘right’ to travel at the speed-limit, regardless of the conditions

- ‘bunching’ on motorways/freeways and highways because everyone is driving at the same ‘maximum’ speed, with no legally-permitted option for a quick burst of speed to overtake

- drivers attempting to drive at the (dry-conditions) speed-limit on wet or icy roads

- drivers tailgating and pushing at others who are driving below the speed-limit because the conditions are not safe for the specified-limit speed

- drivers going past schools or other ‘child-at-risk’ areas at full limit speed

In SCAN terms, what we have with a speed-limit is a Simple rule being used as a proxy for the whole-context, overriding the necessary roles of algorithms (for Complicated by calculable contexts), patterns (for more-Ambiguous contexts) and principles (for Not-known contexts):

Which means, in practice, that the Simple rule is then taken as the primary test for safe versus not-safe driving. Which lays the whole space wide open to all manner of absurdities and abuses – such as the spurious accuracy of tools such as speed-cameras, which give very high-precision in a context which is very blurry indeed. Which, in turn, incites many definitely-not-safe tendencies amongst drivers, including:

- focussing on the speedometer more than on the road

- searching for speed-cameras rather than road-hazards

- attempting to ‘game’ the system by attempting to ‘get away with’ higher speeds than the road-conditions would actually permit, solely because a speed-camera is not present

- again, asserting a ‘right’ to drive at the maximum listed speed-limit, regardless of road-conditions

And then, from the other side, we have the classic ‘rule-follower’ and ‘target-orientation’ dysfunctions:

- speed-cameras issuing non-repudiatable speed-tickets, regardless of context, to emergency-vehicles or other drivers who may need to travel above the speed-limit (e.g. taking someone to Emergency unit or Obstetric-Delivery unit at hospital)

- speed-cameras set at a higher precision than speedometers actually tolerate (e.g. in Victoria, Australia, speed-cameras are set to trigger nominal at <3kmh above speed-limit, whereas most speedometers are still designed only to 10% accuracy (6kmh in most urban areas) and recorded-speed displayed on speedometer versus actual speed-on-road varies with temperature, tyre-pressure etc; also speed-camera precision is affected by placement, vehicle-shape etc)

- zero-tolerance for road-topology issues such as natural speed-up on descent of a slope

- police-officers who are low on ‘target quota’ for charges/arrests may search for excuses to use speed-limit issues as an ‘easy’ mark or metric for their own ‘performance’-activity

Throughout all of this, the problem is that there is a fundamental disconnect between the ‘how’ (the speed-limit) and the ‘why’ (safe-driving). The pseudo-precise rule (the numeric metric for the speed-limit, in this case) is used as a proxy for what is actually needed (in this case, safe road-usage according to variable context). The rule’s preset metric may well be too low, or, in many circumstances, too high, for the conditions that apply at that moment.

The rule has insufficient fuzziness for the actual needs of the context. Or, to put it the other way round, the requisite-fuzziness of the context is greater than the fuzziness or uncertainty allowed-for by the rule. In exactly the same sense that a control-system that manages less variety than the requisite-variety of the context cannot actually ‘control’ the behaviour within the context, a rule (or algorithm, or pattern, or principle) that allows for less variance than the requisite-fuzziness of the context has a high risk of being more of a hindrance than a help in many of the circumstances that can occur within that context.

Remember, though, that speed-limits and suchlike are just one example of spurious-precision and inadequate-fuzziness. It’s not just that there’s ‘many examples’, either: they’re everywhere – especially within business-organisations. (Probably the classic business-example? – “Our strategy is last year plus 10%”…)

So for enterprise-architects and others, whenever you see a rule that’s based on a preset metric, always ask:

- where did this metric come from?

- does it actually indicate what it claims to do – i.e. a true trigger-condition?

- does it encourage awareness of and alignment with the real aim behind the rule and metric – or distract from that aim?

- does it support awareness of the real requisite-fuzziness in that type of context – or distract from that awareness?

Makes sense, I hope? Over to you for comment, anyway.

This and the qualitative metrics conversation raise some important questions about what for lack of a better term I will call “mindset”. The sidebar discussion on the distinction between art, craft, science and engineering is also relevant, as science and engineering are about objectively measurable things, while art and craft are not.

I like the idea of “requisite fuzziness”. I have often said that architects rarely say anything that doesn’t start with “Yes, but …” or “It depends.” (An architecture team that I led at Digital many years ago gave me just such a pair of rubber stamps.)

In the qualitative metrics discussion, Alan Kelly mentioned Goodhart’s Law. There’s another similar “law”, though I don’t know if it has a name, which is that a focus on measurable things tends to suppress attention to unmeasurable things, and in the worst case, incentivizes behavior that achieves measurable things at the expense of unmeasurable things. This can have adverse consequences; I’m sure we can all tell stories of projects that “made the numbers” but failed to deliver the desired value. Your four questions above imply but don’t specifically ask what I think is the most important question — does the metric measure something that accurately proxies for the desired value (or as I usually express it, fitness for purpose)?

Another consequence of the inappropriate pursuit of quantifiable results is the idea that architecture is about optimization. I hear over and over again that enterprise architecture is about optimizing the business. I think part of this is just sloppy (i.e., colloquial) use of the word “optimize” to mean “improve”, but behind it lurks the idea that enterprise architecture is, or can be, a scientific or engineering discipline. Every enterprise architect ought to instead be conversant wioth Simon’s idea of satisficing.

Alan Hakimi alludes to this problem in a recent blog post of his, “Addressing the Multi-Dimensionality Challenge on Thinking of The Enterprise as a System” (http://blogs.msdn.com/b/zen/archive/2013/02/02/addressing-the-multi-dimensionality-challenge-on-thinking-of-the-enterprise-as-a-system.aspx). Elsewhere I have argued that of course an enterprise is a system, but it’s a people-intensive system, and people and their behavior in the enterprise context are particularly difficult to model and characterize with quantitative metrics.

This leads to my final observation that most of the EA community identifies EA with modeling, and neglects the role of principles in expressing architectures. Again, I think this is due to the prevailing mindset that enterprise architecture either is or ought to be a “hard” discipline. The boxes and lines of even the most abstract models (ignoring the fact that there are many more representations of models than boxes and lines/arrows) lend a comforting feeling of mastery and understanding of the “system”, and wash away all the ambiguity that people bring to the party.

len.

@Len – thanks for solid good sense throughout, as usual! 🙂 A few points to highlight:

“a focus on measurable things tends to suppress attention to unmeasurable things, and in the worst case, incentivizes behavior that achieves measurable things at the expense of unmeasurable things”

Yes, this is a huge source of problems in all manner of areas – the UK National Health Service (NHS) being one of the more egregious political-footballs of this kind at present. (John Seddon has a lot to say about this; also see Ian Gilson’s excellent post ‘What Poses More Danger To The NHS; Dirty Data Or Dumb Leadership?‘)

“Your four questions above imply but don’t specifically ask what I think is the most important question — does the metric measure something that accurately proxies for the desired value”

Again, very good point: I need to be more careful to get closer to the target-issue rather than ‘beating-about-the-bush’ with possibly-extraneous questions.

“Another consequence of the inappropriate pursuit of quantifiable results is the idea that architecture is about optimization.”

Agreed, another huge problem: optimization is a relevant goal for some specific aspects or phases of EA, but should never be described as ‘the’ overall goal for all EA work. (Also note Gene Hughson’s wry aside in his comment to the metrics post, that “Premature quantification is as evil as premature optimization.”)

“most of the EA community identifies EA with modeling, and neglects the role of principles in expressing architectures. Again, I think this is due to the prevailing mindset that enterprise architecture either is or ought to be a ‘hard’ discipline.”

As you may have seen in my recent post on the BPM Portugal conference, this is exactly my objection to modelling-paradigms such as DEMO and its over-‘precise’ ‘enterprise ontology’ or ‘enterprise engineering’ metaphor. (Likewise John Zachman’s beloved metaphor of ‘engineering the enterprise’, which makes no sense once we acknowledge ‘enterprise’ as essentially a human construct.)

There are people in the EA community who focus strongly the role of principles: Danny Greefhorst’s recent book on principles in EA, for example (though I sometimes wonder if it’s more a European approach than an Anglo one?). From my own point of view, I often consider that the real role of EA as a discipline is simply to build and support conversations, with models more as decision-records than anything else (I wrote a post on that some while back, I think?)

“The boxes and lines of even the most abstract models … lend a comforting feeling of mastery and understanding of the ‘system’, and wash away all the ambiguity that people bring to the party.”

Yes, agreed, there’s a real risk of that happening – especially if the modelling-tools and/or -notations do not allow for any concept of modality or (im)possibility and (im)probability of links or entities within the models themselves.

I think the picture gives a nice example of how metrics are communicated. With current technologies there are more innovative ways to communicate speed limits so that you can at least adapt the metric to local & current circumstances (but still within the regulated limits).

The same goes for metrics inside enterprises and enterprise architects should not only questioning metrics but take some responsibility in looking for more innovative ways for dealing with sensory information & metrics/thresholds. Because in the end sensory information & metrics/thresholds are the foundation for all our decision making: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20980586

@Peter: “With current technologies there are more innovative ways to communicate speed limits so that you can at least adapt the metric to local & current circumstances (but still within the regulated limits)”

Ye-es… sort-of, kind-of… Myself, I’d prefer to see less technology and more awareness that reality is a lot more fluid than can be pinned down within some rather crass concept of ‘regulated limits’ or suchlike…

But yes, “the same goes for metrics inside enterprises”: that’s the whole point here, after all. 🙂

Tom, I think you will like the ideas of Hans Monderman, the traffic guru 🙂

http://www.wilsonquarterly.com/article.cfm?AID=1234

I agree with Peter that there is a sense in which “metrics” (he said carefully) are relevant exactly to what Tom is saying. Some means of assessing how much fuzziness is requisite is not merely useful but essential – as long as we understand that what we are measuring is probabilistic and cannot be expected to produce a deterministic solution.

In this sense the scientific comparison is with quantum mechanics rather than with Newtonian physics. And just as in quantum mechanics we have to understand the observations we make differently than in classical experimentation.

But it’s a good challenge, Peter and I for one will give it more thought.

@Stuart: “as long as we understand that what we are measuring is probabilistic and cannot be expected to produce a deterministic solution”

…and…

“In this sense the scientific comparison is with quantum mechanics rather than with Newtonian physics”

In both cases, yes, that’s exactly the point – and likewise the corollaries that follow on from that.