Every organisation is ‘for-profit’

What’s the fundamental difference between a for-profit organisation, and a not-for-profit one? Or, for that matter, between either of those and, say, a government department, or an NGO (non-governmental organisation)?

Short answer: none – because every organisation is a for-profit organisation. The only difference between organisations, in that sense, is the value-system via which they identify and measure their respective profit.

And the only reason why we have this otherwise-meaningless distinction between ‘for-profit’ versus ‘not-for-profit’ is because the cultures we live in have arbitrarily elevated a single proxy for value – money – to the level where they believe that it’s the only valid measure of value, and hence of profit. It isn’t: in fact it’s often the worst possible metric we could use.

(That’s true even for commercial businesses – witness Michael Porter’s assertion that “the obsession with ‘shareholder-value’ is the Bermuda Triangle of strategy’, in which companies sink without trace”…)

To make sense of our organisations, we need a better understanding of profit – what ‘profit’ really is.

We also need a better understanding of the nature of enterprise, and what that really is.

The common view is that the organisation ‘is’ the enterprise: but that’s not a wise view to take. They’re fundamentally different: an organisation is an abstract concept, bounded by rules, roles and responsibilities, whereas an enterprise is literally a thing of emotion, loosely framed by shared vision, values and commitments. Their bounds can coincide, but if we do that, it literally leaves no room for a shared-story between the organisation and anyone else.

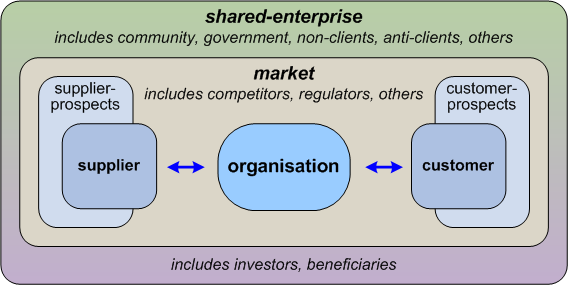

A more useful description is when ‘the enterprise in scope’ is some three layers larger than ‘the organisation in scope’: organisation, supply-chain/value-web, market (or equivalent), and shared-enterprise. Or, in visual form:

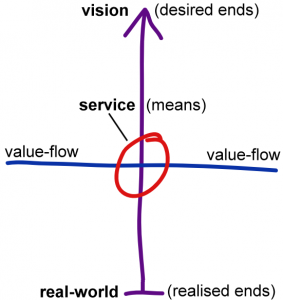

To use terminology from Enterprise Canvas, the core reason why anyone does anything is that there’s a tension between what we have (realised-ends in the real-world) and what we want (desired-ends or vision).

A shared-enterprise exists whenever and wherever there’s a shared-vision – some kind of desired-ends that are shared by and with others.

Crucially, enterprise-vision is expressed as enterprise-values, which in turn are expressed as enterprise success-metrics. Although any player within the shared-enterprise may also include additional definitions of ‘success’ for use within their own specific context, those additional success-metrics must always be in context of and subordinate to the success-metrics of the shared-enterprise, because otherwise the success of the whole shared-enterprise – and hence the success of every player within it – would be placed at risk.

A market exists to provide guidance and regulation – ‘rules, roles and responsibilities’ – for active players within the shared-enterprise, to help keep them on track to those shared-aims, shared-values and shared success-metrics of the broader enterprise.

As an active player within a shared-enterprise, the organisation presents services (means toward ends) to assist other players in reaching towards the shared-aims of the respective enterprise. In this way, various forms of value – ‘products and services’ – will flow around between the players in the market and broader enterprise:

A service’s value-proposition indicates to other players how this organisation can assist them in reaching towards the shared-aims of the overall enterprise. Yet the means by which it creates value for and with others (the ‘horizontal’ value-flow in the market) is always in context of the success-metrics of the shared-enterprise (the ‘vertical’ anchor-thread of enterprise vision and values). The service exists, or rather places itself, at an intersection of values and value – and a key role of value-management or value-governance is to ensure that value-creation by the service keeps on-track to those enterprise-values:

As that diagram of the enterprise earlier above would imply, everyone in the shared-enterprise is a stakeholder in every service within that enterprise.

In that sense, everyone is an investor in some way in every service, and everyone is a potential beneficiary. The forms of value that they each invest, and that they expect and/or receive in return, may vary somewhat in almost every case. For example, donors to a charity might invest money, whilst others might invest their time and personal commitment – and all of them would hope to receive the dividend of satisfaction at the outcomes of the charity’s actions towards the vision and aims of the enterprise. A family would invest their time, and often a lot of their money too, in raising their offspring, helping them through college, perhaps also in setting up a business and a household of their own, and generally helping them deal with life’s various trials and tribulations – yet the reward, again, would mostly be in terms of parental satisfaction rather than money.

In short, ‘profit’ is the ‘excess value’ from a service’s operations that it returns to its beneficiaries. Note that, as in both of those examples above, the invested value may well go through many translations and transforms as it’s used and applied within the operations of the service – and may come back out again in an entirely different form from that of the original investment when it returns as nominal profit.

The key here – as again implied by that whole-enterprise diagram – is that in a viable enterprise, investment, return and profit are always in context of the enterprise vision and values. Yet as with the enterprise-values, the forms of value in investment and return are often very different from the ‘horizontal’ value-flow – which might well focus more on, say, toothbrushes, or breakfast, rather than the investment of money and hope.

Within an enterprise context, return on investment will always be a variously-complex mix of “what’s in it for me” and “what’s in it for we”. Given that, and the inevitable translations and transforms of value, each service will usually need explicit functions, capabilities and subsidiary-services – some embedded within the service itself, some via ‘external’ links – to manage the transforms and the links to enterprise-values, and to keep everything fair and in balance for all the respective stakeholders.

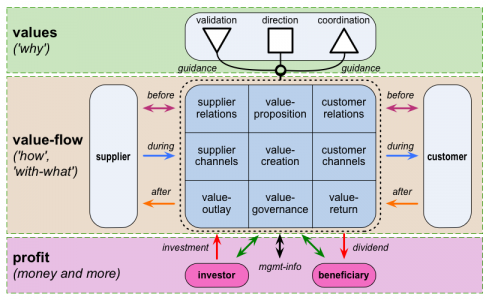

Mapping this out with Enterprise Canvas helps bring some clarity to all of these relationships:

- the core service itself (in this case, the organisation as a whole), and its value-flows with its suppliers, customers and other direct participants in its value-web

- the various guidance-services (direction, coordination and validation) that are of but not necessarily in the service, and that help keep it on track to enterprise-values

- the investors and beneficiaries, who support and underpin the service in context of the overall shared-enterprise

We can summarise all of this visually as follows:

The interrelationships and interdependencies between these activities and stakeholder-roles provide a systematic map for a viable service – one that can deliver its services indefinitely into the future, in accordance with its own success-metrics and those of its encompassing enterprise.

A viable service always returns some form of profit to its beneficiaries: and likewise, in that sense, every viable organisation is a for-profit organisation, in symbiotic relationship with investors and beneficiaries and the shared-enterprise as a whole.

But here, unfortunately, is where things often go badly wrong…

And the key clue as to how and why it goes wrong is in that seemingly-arbitrary distinction between ‘for-profit’ and ‘not-for-profit’.

In essence, every so-called ‘not-for-profit’ organisation – including government and the like – will follow the kind of structure shown above. It has to, if it’s going to be viable in the longer-term.

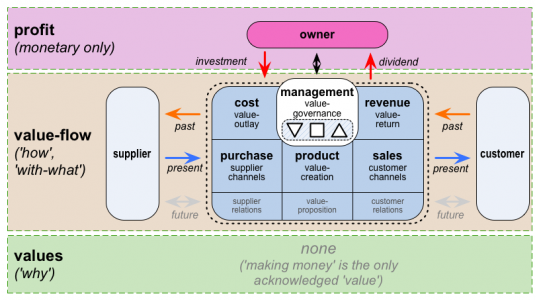

By contrast, what’s usually called a ‘for-profit’ organisation – a conventional corporation or commercial business – is often required by law to take on a structure that is almost the exact inverse of this: the so-called ‘normal’ structure for a ‘for-profit organisation’ is literally back-to-front and upside-down from that required for viability. We can summarise this inversion visually as follows:

This is the kind of structure that underpins classic Taylorism, for example. The starting-point for this inherently-disastrous model of the organisation is a set of arbitrary assertions:

- the only meaningful form of value is money

- the only acknowledged form of investment is in monetary terms

- those who invest money in an organisation become the exclusive ‘owners’ of every asset in that organisation, and hence of the organisation itself

- as the owners of the organisation, the monetary investors are entitled to all of the returns from that organisation

- because the only meaningful form of value is money, all returns from the organisation must be converted to and measured in monetary form

- the only reason that a ‘for-profit’ organisation exists is to ‘make money’ for its monetary investors

I won’t go into the detail here – though see, for example, my series of posts on ‘Four principles for a sane society‘ – but the blunt reality is that none of these assertions have any sane basis in real-world fact.

Some of the consequences of these dysfunctional assertions include:

— Institutionalised narcissism: As indicated in the diagram above, the inversion forces all guidance-services to be conflated into what would otherwise be ‘value-governance’, and thence distorted into what is now usually referred to as ‘management’. Since all of the otherwise ‘outward-aware’ guidance-services have now been brought ‘inside’ just one subsidiary-service within the organisation, there is no means to connect with what is going on in the broader business context, leading to a common tendency to interpret all internal beliefs as ‘fact’, in a self-centric, self-obsessed way. The only connection with the ‘outside’ is via ‘the owners’; and the only means to describe the outside world are in monetary terms. This provides extreme constraints on the organisation’s ability to make sense of its business-context.

— Institutionalised myopic conservatism: The ‘value-governance’ services, here expanded out to a supposedly all-encompassing ‘management’, connect primarily with the value-flows shown as the ‘past’-oriented backchannel in Enterprise Canvas. The natural flow of the service-cycle is inverted, with emphasis placed in reverse time-order, from past, to present, to a largely-ignored future. The result is that the future is interpreted almost exclusively in terms of the past – metaphorically equivalent to driving a car guided only by what can be seen in the rear-view mirror. This almost invariably leads to strategic errors such as “our strategy is last year plus ten percent”, and tactical errors such as trying to manage by targets. The problems are further compounded by market analysts who likewise assert ‘predictions’ of future behaviour based on past performance; and in some countries – perhaps especially the US – these problems are further exacerbated by corporate law that demands past-orientation and short-termism, such as mandated ‘quarterly results’.

— Institutionalised disconnect from enterprise: This is a direct consequence of redefining the ‘vision’ to ‘making money for the owners’, and in turn has a whole swathe of direct side-effects, such as:

- having lost its ability to connect with anything greater than itself (i.e. a shared-enterprise), the organisation comes to regard itself as ‘the enterprise’ – leading, again, to a narcissistic, self-centric view of its business context (“our vision is to be the Number One provider of…”)

- without ability to create values-based connections with others, the organisation is forced into ‘push-marketing’ – requiring constant effort to maintain, and frequently at risk of a spiralling ‘race to the bottom’ in competition-against relations with others

- without a connection to any values beyond money, that could provide natural guidance and touchstones for ethical business-behaviour, the organisation is constantly at heightened risk of unethical behaviours from within and beyond itself

— Institutionalised expropriation – otherwise known as theft – from all non-monetary investors and stakeholders: Another direct consequence of the requirement to force all value-relationships into monetary terms is that every non-monetary form of investment is either ignored – and hence deemed to be without ‘rights’ to monetary return; or re-translated into monetary form – in which case it is deemed automatically to be the sole property of the monetary investors. Either way, the disincentives against needed non-monetary investment, and/or anger against an organisation, can build up and up, sometimes exponentially, yet apparently ‘without warning’. This was what happened in a real case I dealt with in Latin America: the organisation went from the most-respected in the region, to the least-respected, in just six months – and only then realised that they had a serious survival-threatening business-problem on their hands, with no idea how it had happened or what to do about it…

Another very serious problem for commercial organisations, and for society in general, relates to the respective priorities given to different types of investor-relations. In a previous post I summarised five types of investor-relations:

- symbiote (primary-investor) – committed to the aims of the enterprise

- parasite (beneficiary-investor) – interested primarily or solely in returns to self

- grazer (market-investor) – invests in the market, not the organisation

- predator (attack-investor) – invests for the purpose of gains from destruction

- scavenger (derivative-investor) – invests solely to ‘game’ disruption within the market

As in the viable-service model described above, the only non-dysfunctional investor-relationship occurs when organisation and investors act as symbiotes for each other. However, in stock-markets and the like, we see exactly the same kind of ‘back-to-front-and-upside-down’ inversion as in so-called ‘for-profit’ organisations: the investor-types are assigned priority in the exact reverse-order needed for viability – scavenger first, symbiote last. The result is that the problems described above occur not just within individual organisations, but are magnified across the entire economy, right out to a global scale.

In short, those common distinctions between ‘for-profit’ versus ‘not-for-profit’ may well be mandated by law, but they are inherently dysfunctional, highly misleading, and frequently cause serious damage to commercial and other organisations, and to society as a whole. The only way to avoid those forms of damage is to acknowledge, understand and design for the fact that every organisation is a for-profit organisation, for all of its stakeholders – and that the definition of ‘profit’ comes from the values of the broader shared-enterprise, and must be broader than just money alone.

Implications for enterprise-architecture

All of the above has huge implications for enterprise-architects, business-architects, business strategists, service-designers and anyone else tasked with the design, structure and operations of just about any kind of organisation.

As above, the problems can be particularly severe in commercial organisations, because so much the inherent-dysfunctionality of the Taylorist-type ‘for-profit’ structure is actually mandated by law. It can also be very difficult – particularly in the US, for some reason – to get business-folk or even the wider culture to understand ‘value’ in anything other than monetary form: yet without that awareness, viability in any form becomes an ever-more-elusive goal.

Often the only way to resolve this is to design in accordance with proper whole-of-enterprise principles, but to present the results of the design in accordance with the (delusionary) expectations of a money-only model. Yes, it’s ‘stealth-architecture’, and hence potentially somewhat of a risk for the architects: yet the monetary-returns just from reducing some of the huge inefficiencies of a conventional Taylorist-type model should more be than sufficient to distract attention from how those gains were achieved. Once the real value of a whole-enterprise design-model has been established, it should then be easier to explain how and why those principles work, and bring them to become more overtly embedded in the organisation’s structure and operations. There are plenty of successful ‘value-driven’ organisations to use as examples here – and also a fair few that have been all but destroyed when those principles were abandoned by a new CEO or more money-oriented board of directors – all of which show what works and what doesn’t in real-world practice.

In other words, it’s all doable: it’s just that we often have to keep a bit quiet about it at first.

To give a practical example, consider a more enterprise-oriented way of using Business Model Canvas:

Most of the Canvas would be worked on and populated in the usual way, much as described in the book Business Model Generation, though with a few additional tweaks – most of which are relatively minor, and hence, for space reasons, I won’t need to go into here. However, there are significant differences to how we work with three of the cells:

— Value Proposition: Most of the descriptions in Business Model Generation imply an ‘inside-out’ or ‘push-marketing’ model. This needs to be rebuilt around an ‘outside-in’ or preferably more-symmetric ‘pull-marketing‘ model, based on whole-enterprise vision and values. (See the post ‘What is a value-proposition?‘ for more detail on how to do that.)

— Cost Structure: In Business Model Generation, costs are described solely in monetary terms. This needs to be expanded to include structures and mappings for costs of all types within the shared-enterprise – as indicated or implied by the enterprise vision, values and success-metrics – and also interactions with and interfaces for the various enterprise-stakeholders who provide investment to cover some of those costs.

— Revenue Streams: In Business Model Generation, revenue is described solely in monetary terms. This needs to be expanded to include returned-revenue in all forms of value arising in service-transactions – all value-forms indicated or implied by the shared-enterprise vision, values and success-metrics – and also interactions with and interfaces for the various enterprise-beneficiaries who receive value-returns of excess-value extracted from the business-model’s operations.

Although it’s not covered in Business Model Generation, we also need to model value-governance – how balance is to be maintained between all investor-stakeholders, beneficiary-stakeholders, and the organisation itself.

And yes, there’s quite a lot to it – a lot more than is seen in most conventional business-models, at the least. But it’s also the only way that works – especially in the longer term…

Anyway, that should give you more than enough to think about for now 🙂 – any comments, anyone?

Tom,

a brilliant post — thank you. You presented a concise yet surprisingly comprehensive summary of your published work and then you took us a big step forward.

The basic tenet — every organisation is for-profit — has large implications: it facilitates transfer of insights between the former for-profit and not-for-profit sectors. As often is the case with discoveries like this, this statement seems obvious *in hindsight*.

Better integrating the enterprise and biz model canvases seems worthwhile to me. I agree what you said above about value governance, and about missing partner relationships & channels in “Mapping the Enterprise”.

I’m wondering whether key resources & activities ought to straddle the cost/revenue divide: after all, they realize the value proposition and are essential to generating revenue (value returns?) by (co-) creating value.

Cheers,

Oliver