NOTES – actors, agents and extras in the enterprise

If the enterprise is a story, who are the actors in that story? What are their drivers and needs? How do we model and manage the relationships between those actors in the story?

(This is part of an overview and how-to for an alternative approach to enterprise-architectures and the like, called NOTES (Narrative-Oriented Transformation of Enterprise [and] Services. Previous posts in this series include ‘NOTES – an alternative approach for EA‘, ‘NOTES – putting it into practice‘ and ‘Some notes on NOTES‘.)

For comparison, if we take the classic view that the enterprise consists of people, process and technology, then this mostly aligns with the ‘people’ bit. (Mostly – there’s a bit more to it than that, as we’ll see in a moment.) And for this, we need to think in terms of actors, agents and extras.

Actors

The classic views of business tend to have quite limited ideas about where people fit into the business, their roles, and their relative priorities.

For example, who is the business for? Many would argue that it exists primarily to make a profit for the shareholders – that that’s the single highest priority of all. In which case, what actually are the roles of employees, customers, analysts, auditors – where do they all fit into this money-making picture? In story-terms, we’d see straight away that there’s a problem here: a story so one-sided that it’s barely a viable story at all – not one that would make much sense for anyone else, anyway. If we want to engage people in the story, we need to create a space and a purpose in which they too can be of the story – otherwise why would they bother?

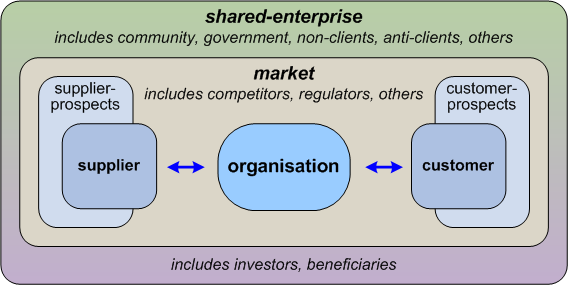

Again, a classic view of business is in terms of its direct business-relationships. People supply stuff to us, we do something-or-other to it, and we then sell the resultant stuff to someone else. Or, in visual form, kind of like this:

In return for the stuff they provide, people get paid – including, we hope, the people in our organisation. What comes in from our customers we call revenue, and what goes out to our suppliers, and (if we can be bothered to pay them for the ‘privilege’ of working for us) our employees, is what we’d call costs. (From a systemic perspective, ‘costs’ and ‘revenues’ are actually the same overall flow or ‘back-channel‘ – they’re just different views into arbitrarily-selected points on that flow.) Revenue minus costs is what is popularly called profit, which is then passed to the stockholders.

So in a simple organisation-centric supply-chain view of the enterprise, those are the only actors that count: suppliers, customers, employees and stockholders. That’s it.

Which is, again, kinda limited. To make sense of the enterprise, we need to look a bit wider – which also means bringing a wider range of actors into our awareness.

The first step outward is to see it not just in terms of the direct relationships, but more in terms of nodes in a supply-chain:

There’s a degree of indirection here: our revenues or costs – and hence our profits, too – can be dependent on things that happen, and business-relationships that exist, beyond our direct control. And yeah, that can be uncomfortable…

The next step outward from that is the organisation in context of the respective market:

Here, what we’d previously seen as a simple supply-chain – with our organisation always at the centre – now expands out into a whole value-web of business-relationships. Some of these relationships may not touch our organisation at all – they may pass only through our competitors, perhaps, or our equivalents in other regions outside of our own business-scope – but they will all affect us in variously-indirect ways. For example, if the overall market is caught up in a scandal or a crash or a commodity-shortage, our organisation will end up wearing some of the resultant costs, whether or not we were part of the cause for that problem.

In other words, a lot more actors in our business-story of whom we perhaps need to be aware.

Yet there’s still at least one more step we need to go, because there are yet other actors on the more outward fringes of the shared-enterprise who, even though we may hardly interact with them at all, can still have huge impacts on our own business-story. In some ways they’re more like the ‘audience’ for the overall market-story, and for all of the organisations and other more-visible actors in the market – and they are the ones who really decide whether the story succeeds or fails:

Yeah, a lot of actors…

In short, in a narrative-oriented view of the enterprise, ‘the actors’ aren’t solely the ones that we can see ‘on stage’:

Instead, ‘the actors’ of the story include everyone who’s involved in the story, in any way whatsoever – the players, the process-operators, the technicians, the managers, the direct and indirect audience, everyone:

And they’re all needed in the respective whole-enterprise story – otherwise the enterprise wouldn’t be what it is.

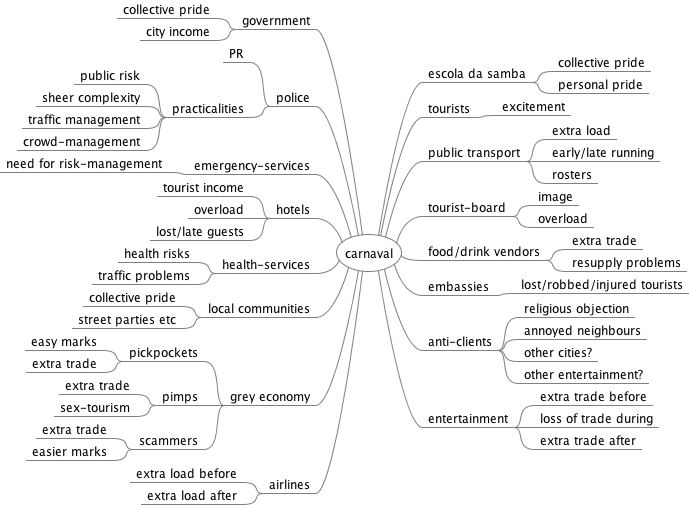

The other point is that although each of the actors is in the same story, they also each have their own personal stories that intersect with this story. And actors have their own distinct motivations and drivers even within this shared-story. For example, consider the motivations and concerns of just some of the players within a large shared-enterprise story such as Rio de Janeiro’s Carnaval:

This is what gives shared-enterprise stories their variance and richness: each combination of players gives us what is, in effect, a different story, yet always with at least one common shared-theme – ‘the enterprise’ – that connects and links together all of those different context-specific stories.

Agents

Some of the less-visible actors in the story will be represented by automated agents – machines, IT and suchlike. We’d often regard these as part of the setting and stage for the story: yet whenever they take an active role in the story – in other words, as ‘agents’ of and for the story – it’s best to view them as just another kind of actor, each with their own motivations and suchlike. Two points arise from this:

— From a story-perspective, it’s often useful to anthropomorphise the agents – give them human-like characteristics, regard them as if they have ‘a mind of their own’, and so on. (Many stories have been built around this theme, from The Matrix to The Little Engine That Could.) Other players will then be able to interact with them as if the agents were human actors.

— Although in theory machines and IT-systems must automatically follow their predefined control-laws, in practice agents do have a kind of motivation of their own, very similar to human actors. For machines, the ‘motivation’ arises in part from physical constraints such as inertia, materials, structure, ranges and degrees-of-freedom of movement and suchlike, but also from longer-term themes such as maintenance-history and general wear-and-tear, that can create what is, in effect, a distinct ‘personality’ for each individual unit. And all automated-agents will also tend to embody Conway’s Law, in that their design and function will tend to reflect the culture and motivations of the people and organisation that created and operate them – again giving them a kind of ‘personality’, though somewhat more shared in this case.

[For a perhaps extreme example of machines reflecting the mindset of their maker, see any of the whimsical fantasies created by Rowland Emett, such as MAUD or The Afternoon Tea Train At Wisteria Halt.]

Two other important points to note:

- whether we design for it or not, people will often anthromorphise their relationships with agents anyway – “I don’t like that machine, it’s rude to me”; “that screen is a lot nicer, it has friendlier colours”

- by definition, every interface is or represents a persona – a Mask, literally ‘that through which I sound’

In other words, human-actors may impute motivations for machines and other agent – whether or not those ‘motivations’ actually exist – and act on that expectation. From a ‘rational design’ perspective, those kinds of interactions might seem to make no sense at all; but from a narrative-oriented perspective of the enterprise, they make perfect sense – and in themselves can become key drivers within the enterprise-story.

Extras

In almost every movie or show there’ll be any number of people or agents who are there in the background yet don’t seem to take much part in the action: the extras. What’s interesting is that although they might not seem to do anything of any importance, without them the story stops working – or at best seems somehow kinda empty.

This is perhaps the single most important clue, for business-architects and the like, about how business really works. The organisation is never ‘the centre’ around which the enterprise revolves: the ‘inside-out‘ perspective that the organisation holds is merely one view into a much larger enterprise-story. And no-one in that wider story is ‘extra’ or extraneous to that story: if they’re in the story in some way, the story needs them to be there.

Our organisation may not interact much with the people that we see as ‘extras’, but they’re every bit as important to the overall story as is any other actor. Remember that, unlike a movie-script, an enterprise-story has a life of its own: our organisation engages in that story, in order to do its business with other actors in that story, and has choices in how it interacts with that story, yet it never controls the story itself. Which means that if we’re not careful, nominal ‘extras’ can suddenly become major players in our own business-story.

To understand this, look again at that diagram of our organisation in relation to the overall enterprise:

From our perspective, the ‘main actors’ in our business-story are our suppliers (service-providers), our customers (service-consumers), ourselves (as both service-consumers and service-providers), and our various supplier- and customer-prospects. We might consider business-partners and business-competitors as ‘main actors’ too, if in somewhat more distant roles. People out in the broader market – regulators, analysts, trainers and the like – might have secondary roles or bit-parts within our story. And if we take a conventional ‘inside-out’ view of the enterprise-story, we would pretty much stop there: anyone else is just an ‘extra’ – and hence, we might think, doesn’t matter at all.

Yet there’s much more to the enterprise than just that inside-out view:

- inside-in: our employees and other actors ‘behind the curtain’, or any of our automated agents, can suddenly find themselves ‘front of stage’ in unexpected roles – and in doing so, will inherently change the visible story

- outside-in: our investors and beneficiaries can change our story – and likewise our clients, non-clients and others could become active anti-clients, in new roles that can cause a lot of damage to our story

- outside-out: the overall enterprise-story can change – and hence change the context of our story too

So the fundamental point here is this: there are no ‘extras’ in an enterprise-story. Everyone in that enterprise-story matters to our business-story – whether or not they play an active, visible role in our story. We forget that fact at our peril…

Practical implications for enterprise architecture

Build a map of all of the actors and agents in the respective enterprise (or enterprises – your organisation may well intersect with more than one), and their relationships with the organisation’s story.

[For obvious reasons, apply a ‘Just Enough Detail‘ approach to this. Yet do ensure, though, that you do cover the overall scope of the shared-enterprise – not solely the subset that is directly visible from the organisation’s inside-out view.]

Map out their roles, motivations and drivers, relative to each other within each enterprise-story, and to the organisation and its view(s) of the respective enterprise-story. (Just roles, motivations and drivers for now: we’ll explore story-lines, interaction-events and suchlike in a later post in this series.)

Some themes to explore from this:

- What are the tendencies to dismiss some of these actors and agents as near-irrelevant ‘extras’? If that happens, what risks are created, and opportunities missed?

- What impacts for your organisation’s story can be created by interactions between actors elsewhere in the enterprise, even if these don’t connect directly with your story? (Example: legislation created in defence against ‘rogue companies’ in your industry, that create extra burdens for you.)

- What impacts can be created when an automated agent ‘stands in’ for a human actor, or vice versa (such as in disaster-recovery)? What unexpected limitations and changes might be imposed on the interaction-story by this substitution of actors? (Think of this as the business-equivalent of a change of casting in a film or play.)

- What impacts does anthropomorphisation have – where other actors view and interact with automated agents as if they too are human? (This is a key theme in customer-experience, for example.)

Throughout all of this, it’s probably useful to keep focus on a paraphrase of Chris Potts‘ dictum:

Customers do not appear in our processes – we appear in their stories.

Best leave it at that for now: any comments so far?

Leave a Reply