At Social Business Summit London 2013

What’s the best way for businesses to engage with social-media? What are the successes, the traps and gotchas, the new ideas and innovations that work well, the old ideas that don’t?

Those were some of the themes that Dachis Group’s Social Business Summit in London last week aimed to address. Yet how well did it actually do so? A ‘curate’s egg‘ kind of mix, would have to be the honest answer: some good suggestions and some great research, counterbalanced by some absolute howlers – in some cases, practices recommended that are exactly how not to do it…

(Okay, yeah, that’s my own opinion, I’ll admit, but it has some pretty good backing, as I’ll get to later.)

First, though, let’s list a few well-known approaches to social-business that are all but guaranteed to fail:

- using the term ‘consumer’ (or, for that matter, ‘human resource’) in a social-business context

- thinking that social-media represent just another kind of one-way broadcast channel

- thinking that social provides a new kind of ‘captive audience’

- thinking that social is a new means to get ‘consumers’ to provide free labour or free advertising or free anything

- thinking that organisations alone possess ‘their’ brand in a social context

- thinking that the organisation ‘possesses’ a brand-based community

- failing to tell the difference between audience and community

- thinking that employees engaged in social can and must be commanded to remain ‘on-message’

- thinking that the only value and reason for social-business is a new means to ‘make money’ – ‘monetising social’ and suchlike

- thinking that their organisation can somehow ‘opt out’ of social

Unsurprisingly, no-one at SBS offered much support for that last delusion. Yet the blunt reality is that many if not most of the speakers each actively promoted as ‘a good idea’ at least one of those other mistakes, and often more – including several examples where they’d seriously lost the plot. Ouch…

I won’t go through everything in detail – it was about thirty pages of notes, which would be ridiculously long here even by my standards – but I’ll pick out some core concerns, and highlight some of the work that I think is valuable and worth noting elsewhere.

On (not) getting a clue

Throughout the whole day, I kept wondering whether any of the speakers had read The Cluetrain Manifesto – because it sure as heck didn’t look like it…

Way back in 1999, Cluetrain laid out the core foundations for all forms of social-business:

if you only have time for one clue this year, this is the one to get…

we are not seats or eyeballs or end users or consumers.

we are human beings – and our reach exceeds your grasp.

deal with it.

And yet here we were, fourteen years later, with nearly every darn speaker going on and on about ‘consumers’ and the rest, either just the term on its own, or in implied combinations such as ‘earned media’ (getting ‘consumers’ to do ‘free advertising’ on our organisation’s behalf) or ‘activation’ (manipulating ‘consumers’ to work as unpaid labour on the marketers’ behalf), or any number of other variously-insulting terms.

What???

In short, guys, get a clue – don’t do it!

Yes, in classic marketing we can perhaps delude ourselves into thinking always ‘inside-out‘, thinking that we’re the sole centre of everyone else’s world: but that doesn’t work here. In social-business there are no ‘consumers’ (or ’employees’, for that matter) – instead, only peers and partners in a shared social-enterprise. So deal with it, okay? If you can’t engage with others as partners – as equals – then don’t attempt to get involved in social-business: you’ll not only cause your organisation far more harm than good, but you won’t even be able to understand why or how it’s caused so much harm.

I’d guess much of this comes back to those omnipresent desires and delusions of ‘control’ in Taylorist-style organisations: the childish belief that others exist solely to do our bidding, and to support our needs alone. It’s what leads to secondary delusions such as the notion that employees can be constrained to keep ‘on-message’, or that the only real concern of an organisation’s customers is “to consume products and crap cash”, without comment, question or complaint. It is, in a very literal sense, narcissistic – and whilst it might be all-too-normal behaviour for a self-centred two-year-old child, it’s not viable behaviour for relations between adults in a more social context. Hence, once again, get a clue! – it’s long since time that marketers of every kind – and managers – consigned that kind of garbage to the scrapheap of history.

Sigh…

Anyway, on to some of the items that showed rather more sense?

The dark side of social business

That sub-head just above isn’t a put-down, honest! – it’s actually the title of the keynote from John Hagel, co-author of The Power of Pull – a book that every would-be ‘social-business’ marketer should read and inwardly digest…

Two themes I picked up from this session, I guess.

The first was that it’s possible that the only real result of the flood of technology over the past sixty years has been to make things worse for most organisations: a rather extreme example of failure to deliver on promises? The scale is huge, too: since 1965, return-on-assets for US companies is down by 75%. Yet this cannot be blamed on technology alone: much of that collapse of value is due to poor management practices – something that many of us have been trying to explain to Taylorist-obsessed managers since way back in the days of W Edwards Deming. If the management-practices don’t change, the opportunities of ‘social-business’ will be screwed up and lost in the same way, making things even worse than they are already for those organisations. You Have Been Warned etc?

The key point here is that the boundary between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ necessarily blurs in social-business. (Another challenge is that whilst the Taylorist model assumes that the organisation’s boundary-of-control and boundary-of-identity are always one and the same, whereas in social-business they steadily spread further and further apart.) This is something that control-obsessed managers and organisation-centric marketers seem to find very difficult to understand – and tend to handle very badly…

The other theme was around patterns of interaction. John Hagel described research in Deloitte and elsewhere that showed that tightly-integrated teams – as usually preferred by ‘controller’-managers – consistently delivered the lowest performance. Weakly-integrated teams were next-worst. The highest performers were ‘mid-integrated’ – frequently interacting beyond the team, in ways that would be ‘forbidden’ in a highly-siloed organisation-structure. In other words, as John put it, team-performance was directly linked not just to professional competence, but to social interaction as well. “Social interaction, outside of nominal work-tasks, accounts for up to 50% of performance” – a scale of impact than few Taylorist managers would either expect, acknowledge or allow.

This also has key implications for business-performance management. Lag-indicators such as financials are, almost by definition, often worse than useless, because even at best they can only be valid when the context continues onward in exactly the same way – something that rarely happens in the real business-world, especially in these more turbulent times. Operational-metrics such as customer-churn and duration of idea-to-marketable-product can be useful, but limited; by contrast, patterns of social-interaction are fundamental lead-indicators of performance.

One of the best uses for this type of data, John Hagel suggested, was for employees to keep track of their own performance in real-time, creating choices for action and interaction. The catch is that there are huge ethical and other concerns around this: in particular, the data and the choices must be ‘owned’ by the respective employee, not the manager. If there is any attempt to use this for micro-controlling and micro-managing – organisation as ‘the surveillance state’ – then performance will plummet. In short, Taylorism and social-business really do not mix: if you want to get the benefits of social-business, you must drop the Taylorism – you cannot have them both at once.

Lighting up the world

A few quick notes on the session by Blake Cahill from Philips, talking mostly about their Hue programmable-lightbulb.

One was a quote from Clay Shirky that seemed to echo the same challenge above: “a revolution doesn’t happen when society adopts new tools, it happens when society adopts new behaviors”. To me, for this context, I interpret this as saying that whilst social-business can deliver huge rewards, for everyone involved, it can only do so if we drop the Taylorist ‘control’ / ‘consumer’ delusions. Blake Cahill himself seemed to understand this point – for the most part, anyway – but some of the other presenters seemingly failed to do so at all. Worrying.

Next item was about social-listening – keeping track of references in social-media. Blake Cahill said that at present marketers still aren’t good at this. By contrast, he said, “In Zara and H&M, the main social-listeners are in the supply-chain”, listening for trends, to tighten up on lead-time to get new fashion-designs to the market.

What worried me here, though – as in too many of the other presentations – was example after example of “How to create anticlients on a massive scale”, and an apparent total lack of awareness of any of those risks… For example, the Hue lighting-system is brilliant (pun intended), and a great demonstrator for Internet of Things: and yet, when Cahill explained that “we can watch every [Hue] lightbulb in the world, and the colour it’s set to”, he seemed completely unaware of the privacy-issues or hacking-risks implicit in that statement. A key role for enterprise-architects, perhaps, to help marketers connect back to the sometimes brutal realities of the real-world?

A rough diamond

Throughout much of the session by Davidé Casali of Dachis, I was delighted to find myself scrawling “gets it… gets it…” in my notes – not consistently, by any means, but at least a pleasant change from some of the howlers elsewhere.

The session was nominally about ‘How to manage a motivational brand’, but to me the most important parts were where he focussed more on what a brand is. He drew a useful distinction between logo, mark and brand:

- logo: identifies a property [i.e. a company ‘possession’]

- mark: represents trust [i.e. shared between company and others]

- brand: represents a way of being [i.e. denotes a community]

The crucial point here is that whilst the organisation is responsible for a brand, it does not possess that brand. The brand ‘belongs’ to the community as a whole (‘a totem pole to unify the tribes’, to quote one of my enterprise-architecture clients) – and the organisation will kill the brand if it tries to ‘possess’ it.

Brands, said Davidé, “have a natural community, following and identifying each other with a shared set of beliefs and lifestyle”. (The key example he gave was Harley-Davidson.) “Brands are inherently social, because they are inherently community – tribes.”

He suggested that every brand needs a core focus, which he described in terms of a four-quadrant model, mapped out as a rough diamond:

- competition: collective focus – competition with or ‘against’ others

- excellence: personal focus – competition with or ‘against’ self

- curiosity: view or explore – especially the different or the new

- affection [and caring]: depth-connection – ‘reaching into the soul’ [my term, not Casali’s]

The example he gave for a ‘competition’-based brand-community was Red Bull. Yet to me, looking at events such as the Red Bull Stratos space-dive, the Red Bull brand represents more than just ‘competition’ alone: it includes many ‘excellence’-elements as well – which suggests that his ‘quadrants’ could or should be seen more as dimensions rather than discrete categories. When I asked him about this, he agreed, but said that the reason he used a category-based frame was that if he didn’t present it that way, marketers would want to try to cover every part of the whole map – leading to a loss of focus. Instead, he said, just pick one to start with: the fine-detail comes later. From an enterprise-architecture perspective, that approach seems way too constrained and shallow for my liking – but given the lack of depth-awareness so often evidenced elsewhere in the day’s sessions, I’d have to admit that those constraints might well be necessary, to keep over-excited marketers at bay… 😐

Another comment gleaned from something called the ‘Meaningful Brands Survey’: in the US, 92% of ‘consumers’ couldn’t care if every brand disappeared. “What are we doing wrong?” asked Davidé. My answer: it’s because trust of brands has been lost, by too much misuse of that trust. As Davidé himself had said earlier, a brand belongs to a community, not a company: if the company tries to portray a brand as its own exclusive ‘possession’, then loss of trust in that brand – and, even more, in that company – will be the inevitable outcome.

No more ‘spray and pray’

A few quotes from Jeff Dachis, and my associated comments

— “We trust the opinions of strangers more than the copy of brand-marketers”

Frankly, given everything seen here and in the marketplace in general, should anyone be surprised at this?

— “The democratisation of sharing of ideas represents the greatest revolution in history, at least since the invention of the printing-press: the ability to express and share ideas, worldwide, anywhere, for free, in HD” [and in near-real-time, too]

This is indeed huge: but the whole point is that it’s not something that marketers can now somehow ‘possess’. At the very least, it represents the end of the old model of ‘control’ or ‘on-message’ one-to-many broadcast: instead, we have an infinity of ‘channels’ that now also enable communications that are any-to-any, many-to-many, and even many-to-one. It’s clear that most organisations and their marketers are still struggling to cling on to a Taylorist-style model of ‘the market’ that simply no longer exists: no surprise, then, that so many have enormous trouble with this change.

— “The old way of ‘spray and pray’ doesn’t work any more”

This another direct corollary of the near-infinity of ‘micro-channels’: the old ‘market-segments’ barely makes sense any more. There are some things that can be done with ‘personalised marketing’ – witness Google AdWords and suchlike – but even that approach is rapidly approaching its own ‘use-by’ date. To me, the real issue is trust, and the concomitant need for engagement with others as equals, as peers, rather than as very-much-unequal ‘consumers’ – and it seems that that’s the one issue that most marketers and organisations still most want to avoid. As Dachis himself put it:

— “Many brands are still stuck in advertising: it’s terrifying to think about engagement, the idea that the brand is out there in the wild. But whether it’s frightening or not, it’s happening.”

The way I’d understand what we need to do is this:

- not ‘consumers’, but constituents in a community – for which the brand acts as a rallying-flag

- not advertising at people, but engaging with them, as partners, peers and equals within that ‘brand-story’

- requires trust and relations and shared-purpose with others – and honesty, too

Almost none of which, at present, most existing marketers and organisations are any good at doing: instead, they’re still trying to cling on to long-outdated delusions of ‘control’. Hence why we see so much ‘old wine in new bottles’, so many endless attempts to rehash old marketing-practices that everyone now knows both won’t and don’t work, simply because the marketers so much want them to work, despite all of the evidence to the contrary. Their choice, of course… but it’s a choice that still annoys the heck out of everyone else – and we would really much prefer it if they stopped flailing in futility, and actually got a clue instead… Oh well.

‘Community’ is not the same as ‘audience’

Glad to say that Robin Hamman of Dachis Group London was another one of those relative-few who did have a solid clue about how social actually works. The core theme of his session was about engaging the organisation’s own workforce in social, but it covered the broader scope as well:

— “Social media needs to be in context of strategy – not just ‘We want a Facebook page'” [as just another advertising-‘channel’]

Yep.

— “If your people don’t understand your strategy, they can’t possibly advocate or communicate in positive ways.”

Yep.

— “Brands have retreated back into broadcast mode – that’s not a community, that’s an [unwilling] audience.”

Yep.

— “Communities are exclusive, they put up barriers and boundaries to protect against unwanted intrusion; but ‘audience’ is just whoever happens to be in a particular place at a particular time.”

Yep.

— [on advocacy] “Give people a one-click button to share stuff; also give them clear information [and why] when something should not be shared.”

Yep.

Enough said, really: solid stuff, all the way through.

Despairing at the downers

Yeah, there was a lot of good stuff there. Sadly, though, there were a few occasions when I found myself almost leaping from my chair and screaming at the presenter – the idea being described was that far wrong in terms of how to relate with an overall enterprise. Here’s one of them:

— “It has to be exciting at the point-of-sale – enhance the in-store experience, in that dead-time in the cash-till queue.”

Here’s a far more sensible idea: fix the darn queue, so that people don’t have to waste a noticeable portion of their lives in pointless ‘dead-time’! Isn’t this obvious to you? If not, why not?

Yes, to the self-centric push-marketer, that might look a free gift of a ‘captive audience’ – someone to sell to! Wonderful! But once we remember to look at it from their perspective – not just yours, for once – then it should be clear that they’re captive in an all too literal sense: they don’t want to be there, they know they’re wasting their time in that queue, and all you’re doing with your ‘exciting in-store experience’ is reminding them of just how much they don’t want to be there. In short, it’s one time when not to annoy people with garbage advertising! Again, get a clue!

The other huge downer, for me, was seeing one of my former social-business heroes provide a long, detailed demonstration of exactly what not to say and do in a social-business context. For example:

— “How do we monetise social?”

Short answer: we don’t. It’s the wrong question to ask in a social context – so don’t ask it!

Yes, monetisation is obviously important for commercial businesses. But successful monetisation is a side-effect of doing social the right way: if we try to make monetisation the start-point of social, it will all fall apart, often in messily expensive ways.

— “Only four sources of value in social: create, communicate, unite, activate.”

A bit limited, though probably fair enough as far as it goes. But:

— “Activate: put the community to work.”

If – as was clear in this context – “put the community to work” should be translated as “use the community as unpaid labour to maximise our own monetary returns” [with no concerns about what commensurate returns could or would accrue to that community], then this is a guaranteed way to create betrayal-anticlients on a truly vast scale – easily sufficient to destroy the entire organisation, in some cases, or even an entire industry. It is exactly what not to say; it is exactly what not to do; it is exactly how not to relate with a brand-community. I was seriously shocked at that statement, and I still am.

— “Only three key content-types [for social-business]: make me laugh; make me cry; make me famous.”

Frighteningly shallow, and in many ways deeply insulting to almost every stakeholder-group in the broader brand-community. Again, I was seriously shocked at this.

— “Only two reasons to do anything [in social business]: make money, or save money.”

Given US business-culture, is it possible that only an American could say something this stupid? – though no doubt there are other marketers from other countries who could give him a close run for his money (pun intended)… Oh well.

Let’s reiterate this once more: monetary profit is a side-effect of successful and respectful engagement with others in social-business. All social-business is inherently complex, with many non-linear, non-reversible transforms: if you try to start from money, and assume that there is then a direct link from there to money, you will fail. Badly. Expensively. Painfully. And you probably won’t have a clue how or why it happened…

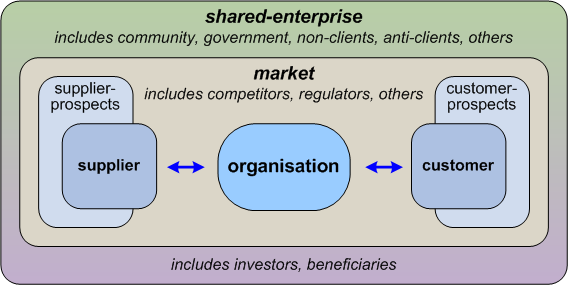

So let’s reframe this whole mess from the perspective of whole-of-enterprise architecture. Push-marketers and Taylorist organisations live within a painfully over-simplified view of the business-context:

Or perhaps, if they’re capable of thinking a little bit wider:

The only thing we should aim to do – we’re told – is to maximise the difference between whatever we can screw out of our ‘consumers’ (‘make money’) versus whatever we can screw others down to in paying our suppliers, our employees, and everyone else (‘save money’). That’s how we get our profit: that’s the only reason for anyone to be in business.

Simple, straightforward, all makes sense, yes?

No.

To be blunt, it’s almost stunningly shallow and stupid… even if it is scarily popular in business-schools and elsewhere.

The reason why it’s stupid is because that simple supply-chain is only one small part of the actual business-context, which looks more like this:

And the flows and interactions across each service within the enterprise are much more complex than merely those of the overly-simplistic linear supply-chain:

Values are what drive the social-enterprise; value-flows traverse across the enterprise, and are usually not focussed on money; and profit can take many forms, of which money is merely one.

Classic Taylorism and classic marketing somehow manage to scramble the view so much that they end up turning it back-to-front and upside-down:

And then wonder why it all tends to fall apart when – as in social-business – they are ‘dispossessed’ of the presumed ‘right’ and ability to ‘control’ the context.

Duh…

Social-Business 101, guys. It’s not difficult: all it requires is to learn how to let go of the delusion of ‘control’ – and it’s a delusion anyway, so holding onto it doesn’t help you, let alone anyone else. So some simple, straightforward, starting-advice here: at the very least, go back to the beginning, back to the Cluetrain, and get a clue – please?

There were good bits too…

Although I’ll say straight away that that last one was pretty bad, I don’t want to end on a downer. Read through all of the comments and notes above: there were good bits there, and a lot of them, too. I’d still strongly recommend it as a conference to go to, if you can get the chance.

Yet perhaps the real key is this: social-business is social first, business later – and the latter only so if business is appropriate in the context. Some of the presenters didn’t seem to understand that point; but some did, and many of the participants I talked with understood it well, too. That alone gives me some sense of hope for the future of the social-business domain. And you, perhaps?

Further reading

These are a few of the articles that have come up for me whilst working around these themes in the past few days:

- JP Rangaswami (‘Confused of Calcutta’): From me to you: the business of sharing

- “I’m used to seeing headlines about people who manage to get asymmetric access to information that was not shared with them in the first place, in an environment where there is neither relationship nor trust. … We need to see headlines about how value is generated from the sharing of information, between individuals, between groups of friends, across society as a whole. That’s really what social networks are about, at home and at work.”

- Sam Fiorella (Sensei Marketing): The Power of Two, or Why Social Media Sucks For Business

- “Social media has led business astray. For all its promised benefits including faster, more effective access to larger communities, it has forced many marketers down a path that leads to lower business revenue. … [F]or businesses, quicker and greater access to larger numbers of people is a false profit, a placebo for broken marketing. Social media experts promised us gold in these social media hills, yet most businesses go home empty handed.”

- Brian Solis (ConvinceAndConvert.com): Funnel Vision: Why Companies Need To See The Light At The End Of The Funnel

- “Customer attention isn’t a switch that toggles on and off — it is a state of perpetual engagement.”

- Harold Jarche (‘Life in perpetual beta’): Social Business Needs Social Management

- “The social enterprise is not yet here, though many talk about it, and confuse it with using social tools. For that, we can blame management. … Trust is essential for social business but management can easily kill trust. Democracy is the counterweight to hierarchical command and control.”

- Meghan M Biro (Forbes.com): Smart Leaders Engage Tomorrow’s Workforce

And a special item for Peter Bakker, who likes to use ‘subway map’ models for just about everything: 🙂

- Gartner Digital Marketing Transit Map (interactive)

Hope you find this useful, anyway – over to you?

Not for almost everything 🙂 just for mapping story settings. The story setting is the first of the five story elements, see http://www.flocabulary.com/fivethings/, and probably the most underestimated one.