Business Model Canvas beyond startups – Part 2: Front-end

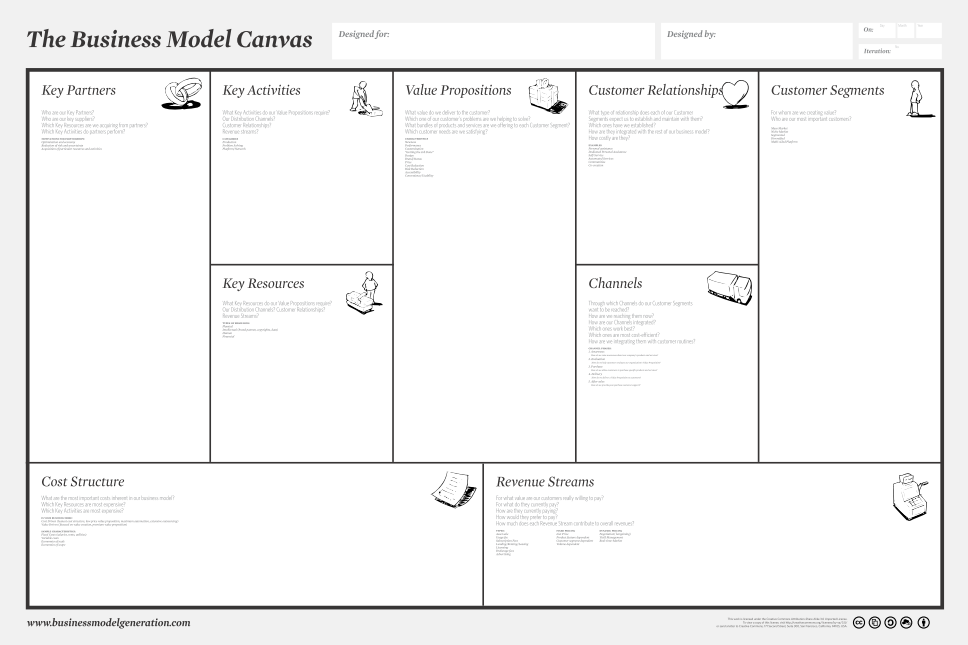

How can we use Business Model Canvas beyond its initial intended context of commercial startups? In particular, how best can we use it to explore the ‘front-end’ of the business-models – the customer-facing parts – for non-profit organisations and government, and existing commercial businesses such as large corporations?

Business Model Canvas [BMC] is very popular in the startup community, and with good reason, because it works very well for that type of context – no doubt about that. Yet its beguiling simplicity and power there depend in turn on a swathe of often-undeclared assertions and assumptions – ones which often don’t work outside of a startup context. To use BMC for non-profits and large organisations, we need to surface those assumptions, assess their implications in each case, and adjust as necessary. Which, following on from the previous introduction-post, is what I’ll aim to explore here.

(See also the posts by Paul Hobcraft, referenced in that introduction-post, that formed the start-point for this exploration. For enterprise-architects, I’d also strongly suggest reading Nick Malik‘s post ‘The EA Metamodel Behind The Business Model Generation‘ – it provides a strong theoretical overview of the internal structure for BMC and how it links to business-strategy and business-motivation.)

So, let’s explore the BMC, block by block, to elicit some of those assumptions. The ‘front-end’ is the right-hand side of the BMC – customers, value-propositions, channels, customer-relationships and revenue-streams:

I’ll go through the structure of the ‘front-end’ of the BMC in the same sequence as in the Business Model Generation book, starting with Customer Segments.

1: Customer Segments

The Customer Segments block is over on the far right of the BMC, and summarises the customer-groups for each Offer (see Value Proposition). On p.20 of the book, the text indicates that:

Customer Segments are distinct if

— their needs require and justify a distinct Offer

— they are reached through different Channels

— they require different types of relationships

— they have substantially different profitabilities

— they are willing to pay for different aspects of the Offer

All fair enough. Note, though, that this is all about the ‘consumer’ side of a service-oriented architecture – which may well be the main focus of a startup, yet a business-model can be made or broken on the supplier-side as much as on the customer-side. Even for startups, we’d usually need to be more aware of that implicit symmetry than is directly supported within BMC.

…a business model … carefully designed around a strong understanding of specific customer needs

Again, all fair enough at first glance, though it could be either push-based or pull-based here. (Push-marketing implies exactly what it says – a lot of uphill push. Pull-marketing instead provides a reason for Customers to come to us – much less effort, and much more reliable and effective.)

For B2B (Business-to-Business), though, we often need clear distinctions between ‘customers’ for the same nominal Offer. For example, the nominal decision-maker may be an executive, whereas the buyer is the purchasing-department, and the user perhaps a customer-service representative – yet they’re all Customers in the context of a business-model.

Business Model Generation makes useful distinctions between different categories of Customer Segment, including:

- mass market – for example, fast-moving consumer-goods (FMCG)

- niche market – for example, anglers, doll’s-house collectors, dental supplies

- segmented within a market – for example, low-end versus high-end fashion

- diversified from an organisation’s perspective – for example, Amazon Retail versus Amazon Kindle versus Amazon Web Services

- multi-sided – newspaper advertising, web-based search

For existing businesses, the main trap to watch for here is the way in which a new business-model impacts on existing customers: alienating the existing customer-base whilst slowly building up a new one can create a cash-flow crisis that could well kill the whole company. It’s essential to model at least the customer-side of the existing business-models before developing ideas for the new model, so that the links and transforms between the two sets can be mapped and designed-for appropriately. For example, the new model can include explicit means to cross-sell to existing customers, whilst reassuring them that the old model will not be phased out anytime soon.

NGOS, government and other non-profits will typically have complex ‘multi-sided’ business-models, for which the usual commercial-type concept of ‘Customer’ is often far too constraining. For example, we once had a Defence client who was trying to use BMC-like supply-chain concepts to model their ‘business’, and realised that if they did so, the only way they could model ‘the Enemy’ was as a Customer!

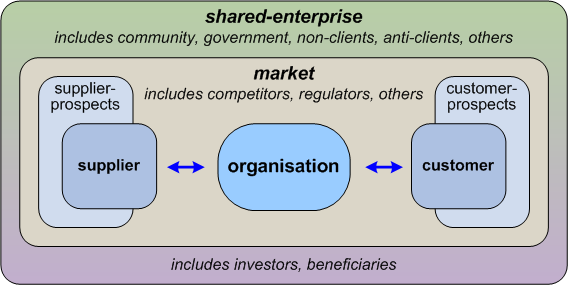

To clarify this, we’d probably need first to use the ‘service-context’ view from Enterprise Canvas, to identify the overall set of stakeholders for the business-model, both in the ‘Customer’ and ‘Partner’ roles in a BMC-type notion of the business-model, but also beyond, to Investors, and Beneficiaries, and outward to anticlients and others in the broader shared-enterprise:

For a charity, for example, a nominal ‘customer-segment’ – representing someone or some agency with whom the charity has direct interactions and/or transactions – could actually hold a relationship to the business-model that could be any combination of Supplier, Customer, Investor and/or Beneficiary:

A key complication here – that isn’t covered in BMC – is that the Investor/Beneficiary flows typically go the opposite way to their equivalents in a supply-chain: an Investor is a ‘supplier’ who provides money (for example) into the service, whilst a Beneficiary is a ‘customer’ who receives money (or some other value-form) from the service.

To make sense of the ‘customer-segment’ relationships in a non-profit business-model, it’s usually necessary first to identify all of the different forms of value in play in the overall business-model, the transforms between those forms of value, and the governance needed to manage and maintain the balances between them. We then link the respective value-forms and value-flows to the respective ‘customer-segments’ – again noting that in some cases a Customer may also be a Partner, an Investor or a Beneficiary, or any combination of those business-model roles.

2: Value Propositions

This block forms the central spine of the whole model. Business Model Generation summarises the role of this block as follows:

The Value Proposition block describes the bundle of products and services that create value for a specific Customer Segment.

Yes, this is a very common way to describe it, but as explained in my post ‘What is a value-proposition?‘, the short answer is that this is almost exactly how not to describe a Value Proposition. It’s a ‘What’, or an arbitrary collection of attributes believed to be associated with a ‘What’ – whereas the core of a Value Proposition must be the ‘Why’ that gives the customer a reason to connect with this organisation in the first place.

In practice, we need to distinguish between the Offer – “the bundle of products and services” – versus the Value Proposition – which expresses why this Offer is of value, in terms of the shared-vision and shared-values of the overall shared-enterprise.

In short, value is always determined by the Customer – not by the organisation. To be blunt, the usual notion of ‘value-proposition’ is a random guess about what customers might want – and hence about as reliable as a random guess, too. To make a value-proposition work, it must connect to the Customer via shared-values – not by arbitrary attributes vaguely attached to a product or service by the organisation’s own wishful-thinking.

The Value Proposition is the reason why customers turn to one company over another.

Yes, it is – sort-of. Subject to the provisos above. Sort-of. It’s a lot more complicated and subtle than described in the book, anyway: again, see the ‘What is a value-proposition?’ post.

It satisfies a customer problem or satisfies a customer need.

Yes – but again, only sort-of. The product doesn’t do this on its own: satisfaction arises from the connection to the success-values of the shared-enterprise, not the attributes of the product alone.

As examples of ‘value-propositions’, Business Model Generation provides this list of attribute-adjectives:

newness; performance; customization; ‘getting the job done’, design, brand / status, price, cost-reduction, risk-reduction, accessibility, convenience / usability

In conventional push-marketing, almost all of these will lead to a ‘race to the bottom’. By contrast, in pull-marketing, all of these can lead to strong differentiation and perceived high-value – but only if linked to the shared-vision of the shared-enterprise. Any value-attribute that doesn’t align with the values of the shared-enterprise – for example, an emphasis on price or cost-reduction within a luxury-oriented market – will probably cause more harm than good.

The book highlights the following ‘key questions’:

- What value do we deliver to the Customer?

- Which of our Customer’s problems are we helping to solve?

- Which Customer-needs are we satisfying?

- What bundles of products and services are we offering to each Customer Segment?

All fair enough as far as it goes, except note the common case in insurance, banking and telcos where the choice of bundling is so tangled and confusing – sometimes intentionally so – that it is all but impossible for the Customer to determine in advance what the actual delivered price or value will be. This creates a huge risk of anticlient issues: a business-model that makes its ‘profit’ by misleading its Customers into over-purchasing will backfire, especially in any market that enables large-scale inter-Customer transparency via social-media.

It’s essential to link each Offer to the respective value-system of the shared-enterprise, and to verify that linkage to the respective shared success-metrics. Openness and transparency are very highly recommended here: they also represent good examples of non-transactional value and values – in other words, values and success-metrics that underpin the long-term relational-assets (person-to-person) and aspirational-assets (person-to-brand) of the shared-enterprise.

For an existing business, the most common danger here is cannibalisation – the new products or services eating away at the market for existing ones, leading to a net zero-gain, or worse. There’s also the risk that a new Offer can distort or damage the reputation or affection attached to an existing brand – in other words, not direct competition with existing Offers, but indirect via the anchor that links the organisation’s Offers to the vision and values of the shared-enterprise.

In both cases, the assessment needs to take into account whatever can be leveraged from existing activities, capabilities and assets – including reputation-as-asset and brand-as-asset. More on that when we look at the ‘back-end’ of the business-model in Part 3.

For a non-profit, it’s essential to use the Value-Proposition properly, to link the Offer to the vision and values of the shared-enterprise – otherwise the Offer will literally have no meaning. Given the complexity of the multi-sided business-models of so many non-profits, it’s also essential to show the cross-links between the respective Offers for each Customer Segment, and show how all of them ultimately support the vision of the shared-enterprise.

For non-profits, the other key, obviously, is to track more than just monetary forms of value: for example, donors to a charity may provide either cash or clothing – perhaps even small hand-knitted teddy-bear toys – and receive satisfaction and sense of well-being in return. It gets complicated… but if we don’t model the values and value-transforms correctly, we’ll have no chance of making sense of the overall business-model.

Also, deciding where to place each stakeholder-group – as Customer, Partner (supplier), Investor and/or Beneficiary – can have significant impacts on how we describe and interpret the organisation’s business-model. It’s often important to experiment with different combinations and positionings, as doing usually leads to new insights about the respective value-exchanges and relationships to the overall Value Proposition, and thence to different Offers appropriate for the respective stakeholder-group.

3: Channels

The Channels block is shown in the centre-right region of the Business Model Canvas. The book asserts that this block:

Describes how a company communicates with and reaches its Customer Segments to deliver a Value Proposition

Again, fair enough in principle – but in practice, unfortunately, the book is very inconsistent about what happens next:

- sometimes Channels are deemed solely to be channels of distribution – the means of delivery of an Offer to a Customer;

- sometimes they’re also channels of connection – as we’ll see with Customer Relations;

- sometimes they’re channels for connecting with anyone and everyone – not just to the Customer;

- sometimes they’re the means via which something is delivered or communicated; sometimes they’re the activities via which that happens; sometimes this can include the content that goes through these channels, and sometimes it doesn’t;

- sometimes they’re just the touchpoints in a customer-journey; sometimes they’re a map of the whole customer-journey.

Even the name varies almost at random: sometimes they’re called Customer Channels, sometimes Distribution Channels, often just Channels. In short, it’s really difficult to make sense of what’s meant to be going on here…

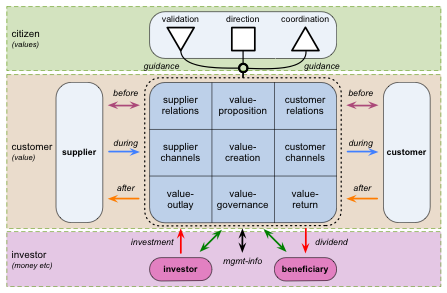

In Enterprise Canvas, we simplify this right down, identifying distinct roles for Channels in terms of the sequence of the overall service-delivery cycle. Each of these ‘channels’ encapsulates the medium of connection, the means and activities of connection, interaction and transaction, and the information, metadata and meta-activities that underpin the creation and operation of the channel. (The description of the channel will also usually include a summary of the content or content-types that traverse through that channel – the Exchange types – though these do need to be understood as somewhat distinct from the respective channel itself.) To paraphrase the book somewhat, we can align these channel-roles to the service-cycle as follows:

- “raising awareness about an Offer” – awareness-interactions

- “helping Customers evaluate an Offer” – evaluation-interactions

- “enabling purchase” – exchange-interactions (‘transactions’)

- “delivering the products and services of an Offer” – delivery-interactions

- “providing post-purchase customer-support” – completion-interactions

The book notes an important distinction between ‘owned channels’ – channels operated directly by the organisation itself – and ‘partner-owned’ – channels operated by some other agency on behalf of and in the name of the organisation. Once again, fair enough, yet there’s no mention – nor, seemingly, any awareness – of the role of shared social-media channels in the pre- and post-transaction phases of the service-cycle. In this sense, BMC seems again to assume a classic organisation-centric push-marketing model – which may well not be either valid or advisable, even in a commercial context.

The book highlights these ‘key questions’:

- Through which Channels do our Customers want to be reached?

The word “want” is important here, not only in the positive, but also in the negative: it’s equally important to ask “Through which Channels do our Customers not want to be reached?”

(If this point isn’t obvious, consider the barrage of pop-adverts blocking your view of a useful website, the relentless spewing of spam-emails in your inbox, or the endless marketing phone-calls that come through just when you’re trying to relax in the evening: do you want to be reached through those Channels? It’s a question that no-one seems to bother to ask – or consider the overall consequences, either, especially in the longer term…)

- How are we reaching our Customers now?

Again, consider the paradigm-shift implied from a transition from push-marketing to pull-marketing: the ways in which we reach and interact with our Customers is radically different in each. Trying to use push-marketing techniques in a social-business context is a quick way to annoy a lot of people… – and yet marketers still try to do it, even now…

- How are our Channels integrated?

Not just economies of scale and suchlike: what we also need to consider here are Customer-oriented themes such as customer-journey, single-voice-of customer and so on.

- Which Channels/types work best?

What evaluation-methods do we need to use here? What metrics? And above all, ‘best’ from whose perspective? – we must include customer-oriented views here, as well as from our own perspective.

- Which Channels are most cost-efficient?

Again, ‘cost-efficient’ from whose perspective? And in what forms of cost? If we assess ‘cost-efficiency’ only from our own viewpoint, and in monetary terms alone, we’re likely to miss all manner of other concerns that can risk rendering the business-model completely non-viable in ‘unexpected’ ways.

To give a simple example, how much do you enjoy those ‘Press 1 for x, press 2 for y’ automated call-centre interfaces? They’re cheap from the company‘s perspective, but they often cause the customer untold costs in time and frustration – especially when the options don’t seem to cover what the customer needs, and there’s seemingly no way to get out of the loop and talk to someone who actually does know more than a robot. Much the same applies to systems and business-models that fail to ‘connect the dots’ across a customer-journey: again, huge costs to the customer in terms of time and frustration – and real risks to the viability of the overall business-model, for everyone involved.

- How are we integrating the Channels with Customer routines?

Once more, ‘Customer routines’ from whose perspective? Chris Potts‘ dictum applies here: “customers do not appear in our processes, we appear in their experiences”. If we fail to understand the implications of that dictum, the business-model will fail – it really is as simple as that.

For existing businesses, there’s much the same trade-offs as in other BMC blocks: how to make the best use and re-use of existing channels, and avoid the risks of over-use and overload on those channels, whilst also being open to the opportunities (and risks) offered by new channels and new media.

It’s also extremely important to use new types of channels in terms of their own natures, rather than just assume that they’re just another variant of the existing ones. For examples, many long-established organisations – and even some new ones too – have made a complete hash of their engagement with social-media. By the nature, social-media are two-way channels, implying a peer-to-peer relationship: trying to use social-media as if it’s an old-style ‘broadcast’ one-to-many channel – as in classic advertising and PR – delivers outcomes that are usually dissatisfying for everyone involved.

For NGOs, government and other non-profits, the challenges around use and re-use of channels are likely to be further complicated by the complex multi-sided business-models that are so often in play in these contexts. Techniques such as customer-journey mapping become essential here, to map out the service-touchpoints and the interactions across each of the respective channels. No real surprise, perhaps, that governments were key early-adopters in those techniques – a trend that continues with government business-support units such as the UK’s Government Digital Service.

4: Customer Relationships

The Customer Relations block is shown towards the upper right on the Canvas. The book states that this block:

Describes the type of relationships the organization establishes with the specific Customer Segments.

I’ll have to admit that when I developed Enterprise Canvas, I’d misunderstood the role of this block. In part this was due to Alan Smith’s illustrations of the Business Model Canvas in the book, which show this block as a double-headed arrow linking between Value Proposition and Customer Segments, symmetric with Channels. In fact the two blocks are not a symmetrical pair: Channels focusses more on means – the channels themselves – whereas this block focusses more on content – the relationships that are created, connected and maintained through a specific subset of Channels.

Sorry, but I’ll have to agree with Nick Malik here: in terms of its underlying metamodel, this part of the Business Model Canvas is a scrambled mess… I’d strongly recommend an alternate way to look at this, as indicated by the service-cycle:

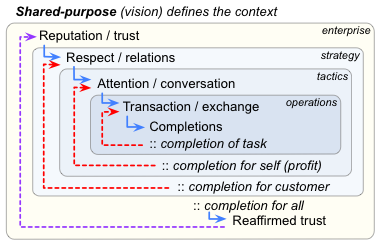

The main content for channels in the Customer Relations block is what, in Enterprise Canvas, would be described as aspirational-assets (person-to-abstract, such as person-to-brand) and relational-assets (person-to-person). In effect, the respective focus-theme for each of these Customer Relations channels is reputation and trust, and respect and relations – the first two phases of the service-cycle.

The main content for what are described variously as channels or distribution-channels in Business Model Canvas – the Channels block – is the set-up for transactions, the transactions themselves, and the immediate follow-up: attention and conversation, and transaction and exchange – the central part of the service-cycle.

And the main content for the final part of the service-cycle – all of the various completions – would pass through channels that provide the means for the final right-hand side block on Business Model Canvas: a much-expanded version of Revenue Streams, as we’ll see in a moment.

But Business Model Canvas doesn’t work that way: instead, it has this stripped-down, rather-incomplete, decidedly-inconsistent mixture of channels and content and role. It sort-of works for startups, where the implications and impacts of those assumptions and simplifications can often be skimmed-over: but in most cases we can’t evade their consequences once we move out of a startup space. Which leads to lots of problems when we try to use Business Model Canvas as a more general business-model tool…

Anyway, more on that as we go along. For now, a comment about motivations, which the book summarises as:

Motivations: customer acquisition, customer retention, upselling.

And that’s it. Which are solely from the organisation’s perspective. Which is not a good idea…

Why isn’t this a good idea? The short answer is that it’s that, for them to be relationships, the relationships need to be, well, relationships: in other words, two-way, not one-way – and a relationship of equals, at that. Fair enough, for several decades now, commercial organisations have commonly assumed (or deluded themselves?) that the only ‘relationships’ they need are outward ‘broadcast’ – ‘keeping on-message’, and so on – and inbound fealty. Otherwise known as the pseudo-‘relationship’ between ‘master’ and slave – or perhaps more accurately the attitude of a two-year-old to the rest of the world. Which doesn’t work for relationships between adults when the natural levelling forces of social-media and suchlike are in play. Which, in turn, means that in this context we need to explore the motivations that underpin the relationships between all stakeholders in the respective enterprise – which is a lot more than just the desire of one stakeholder (the organisation) to manipulate other stakeholders into doing things that they probably don’t want to do…

Moving on, the book summarises typical roles of relationship-types – I’ve added a descriptor to indicate the interaction type in each case:

- personal assistance [human to human]

- dedicated personal assistance [human to human]

- self-service [human to self]

- automated service [machine to human]

- communities [partners – see Key Partners]

- co-creation [partners – see Key Partners]

The organisation may also need ‘hands-off’ relationships with some of its stakeholders – for example, knowledge-management community-of-interest, brand-related fan-club, or product discussion forums.

The book highlights these ‘key questions’:

- What type of relationship(s) does each of our Customer Segments expect us to establish and maintain with them?

Again, mutuality of relationships will be crucial here; also that this applies to relationships with all stakeholders, not solely those described as ‘Customer Segments’.

- Which relationships have we established?

Mutuality again – crucially important, and so often forgotten (or ignored).

- How costly are each of these relationships?

Costly in what sense? And for whom? These assessments must include non-monetary costs, such as time, frustration, skills-loss etcetera; and must be assessed from the perspective of each stakeholder-group – not solely from the organisation’s own perspective.

- How are these relationships integrated with the rest of the business-model?

As above, a better understanding of the service-cycle will probably help here – and likewise a solid understanding of the implications of Chris Potts’ dictum that “customers do not appear in our processes, we appear in their experiences”.

For existing businesses – and for new commercial start-ups too – the greatest trap is regarding these ‘pre-transaction’ interactions as of lesser importance than the transactions themselves: they are part of the same service-cycle as the transactions, and hence equally essential to that cycle. Worse, many organisations place these interactions under the arbitrary heading of ‘cost-centres’, and hence view them as costs to be avoided – rather than as an integral part of the service-cycle.

The result of that error is the ‘quick-profit cycle’ version of the service-cycle, as shown in this more ‘inside-out’ view of the service-cycle:

Although they’re not exactly-equivalent, the effective mapping between the two views of the service-cycle is as follows:

- purpose: strong cross-link to reputation and trust

- people: strong cross-link to respect and relations

- preparation: strong cross-link to attention and conversation

- process: strong cross-link to transaction and exchange

- performance: coordinates the full sequence of completions

In effect, the ‘quick-profit cycle’ assumes that the ‘purpose’ and ‘people’ dimensions are all but irrelevant to business, and hence that it’s always safe, and much more profitable, to not waste any time or effort on them, but instead take a short-cut from the early stages of the Performance phase – immediately after revenue-capture – to the mid-stage of the Preparation – capture the Customer – in order to get back to the next transaction as quickly as possible. In reality, this is neither safe nor wise: in fact over the longer-term it invariably acts as a form of commercial suicide, because it slowly kills off any connection to trust, purpose, values, people and policies, and hence the viability of the service-cycle as a whole.

To make things worse, this risk is exacerbated by the common arbitrary division of business-functions into ‘profit-centres’ and ‘cost-centres’ – with the former to be emphasised as much as possible, and the latter to be ruthlessly pruned as much as possible. From a systems-thinking perspective, this division is not merely misleading, but lethally absurd: every business-function contributes to the ‘system’ of organisation and enterprise that delivers the business’s profit, and hence, by definition, every function in that ‘system’ is inherently both ‘profit-centre’ and ‘cost-centre’, indivisibly both at the same time.

And just to make things even worse, the standard Taylorist-style concept of ‘the firm’ has barely any conception at all of these ‘non-transaction’ interactions. If we use Enterprise Canvas for a moment, the service-cycle moves ‘downward’ through the service-structure, from ‘before‘ (emphasis on trust and reputation, and relations and respect, and to the beginning of attention and conversation), through ‘during‘ (emphasis on attention and conversation, and transaction and exchange), to ‘after‘ (the full set of completions) – all anchored back to the shared-enterprise vision and values via the Value Proposition:

Or, if we take a sideways-on view of the service, with the ‘inside’ to the left, and its ‘external’ interactions to the right, we can see the ‘zigzag’ interactions between the ‘internal’ and ‘external’ views of the service-cycle:

But in the Taylorist-style model of the firm, all of this is turned upside-down. A near-obsessive focus on the past – revenues and costs – takes priority even over the present, whilst the future – in effect, represented by the interactions implied in the BMC’s ‘Customer Relationships’ block, and its equivalents on the business-model’s ‘back-end’ – barely gain any notice at all:

Hence one of the core requirements for development of business-models in a commercial context is turn the model the right way up again – with the Customer Relationships block accorded at least equal priority to everything else – so that the service-cycle can flow properly once more.

Much the same applies to non-profits: for example, government-departments often suffer from the same Taylorist delusions as do commercial businesses. The key point here is in many cases, the Customer Relationships interactions are the ‘transactions’ of the business-model: there’s no actual ‘exchange’ – of anything directly tangible, anyway – hence the respective service-cycle simply skips over that phase, and moves directly to completions. For example, in a medical or social-work context, often simply talking with someone – creating the sense of having been heard – is actually the ‘deliverable’ for the service-cycle. Keeping track of all of these interactions, and linking them all together into a unified whole across a complex multi-sided business, is often the hardest challenge for development of business-models for non-profits.

5: Revenue Streams

The Revenue Streams block is shown on the lower-right of the Business Model Canvas. On p.30, the book summarises this block as follows:

Describes the cash a company generates from each Customer Segment (before costs)

Which, bluntly, is likely to give a lethally-incomplete description of the ‘value-returns’ flows of a business-model…

It’s an over-simplification that we can just-about get away with for a startup: but we can’t get away with it for anything else. The core problems are indicated by a mapping to Enterprise Canvas:

There are three fundamentally-different types of flow or activity going on in a business-model:

- values – determined by the shared-enterprise, indicate definition of ‘success’, linked into via Value Proposition

- value-flow – flows of content, as received from other service-providers (Key Partners), value-added by the organisation (Key Resources, Key Activities, Value Proposition), delivered to the customer (Channels, Customer Segments), and balancing value returned to the organisation (Revenue Streams) and onward to suppliers (Cost Structure, Key Partners)

- profit (‘extracted-value’) – value invested and value extracted from the return-value, usually in a different form from the main value-flow

In essence, Business Model Canvas all but ignores the values anchor, and conflates together all of the value-flow and profit streams into a monetary-only form. To make the business-model work, we need clarity on which is which, and the transforms between them – not merely bundling everything together into an over-simplistic notion of ‘money-as-value’.

Either way, I would very strongly advise to include and keep track of non-monetary forms of value throughout the business-model. Mapping of pre-monetary forms of value in accordance with shared-enterprise values is essential for modelling of key elements in social-business, for example.

The book suggests the following means to generate value-streams:

- sale of assets

- usage fee

- subscription fee

- leading / renting / leasing

- licensing / royalties

- brokerage

- advertising

All of which, again, implies the specific subset of transactions that can be mapped or transformed directly into monetary form. Which is often dangerously-incomplete. All of this needs mapping of pre- and post-‘monetisation’, with an explanation of each transform – and maintenance of any non-‘monetisable’ value!

The book emphasises, as ‘key questions’:

- For what value are our Customers willing to pay?

Equally, for what are they not willing to pay, and why? This helps to identify probable causes of customer-loss or customer-churn, and also potential risks of anticlient issues.

- For what do they currently pay?

‘Pay’ in what sense, for and in what forms of value? – remember that what they pay might well be in non-monetary forms of value, such as time or (absence of) frustration or time-with-family. We also need to note what they at present do not pay for – such as in a ‘freemium‘ business-model.

- How are they currently paying?

Again, remember to include non-monetary forms of cost, and hence non-monetary forms of payment – such as payment in commitment, time, support and suchlike. (For example, customer-support for the UK telecom GiffGaff is provided by its community-members, who in effect pay in part for telecom-services by providing customer-service.)

- How would they prefer to pay?

In a monetary-oriented view of business-models, this would include alternate options for payment-channels, such as credit-card and the like – with concerns such as convenience and simplicity often delivering significant elements for the ‘value-proposition’ (in the simplistic attribute-oriented sense) of the Offer.

Note also the inverse of this – via what payment-mechanisms would Customers not prefer to pay? And as in those examples above, consider also non-monetary forms of value, and non-monetary forms of payment.

- How much does each Revenue Stream contribute to overall revenues?

This is useful for comparing the effective value of different Offer types, but can sometimes be misleading for some multi-faceted business-models – such as freemium or the ‘free-service’ (newspaper, online-search etc) model – or for modelling common operations-level tactics such as ‘loss-leader‘ sales.

With linkage to the core values and Value Proposition, this can also help us to identify criteria for ‘good Customer’, or ‘appropriate’ and ‘inappropriate’ Customers for the chosen business-model.

One further question not addressed here in BMC – but definitely should be – is:

- How does the process of monetisation affect the overall value-relationships?

Transforms from one value-type to another – and particularly to monetary form – always have implied costs and knock-on effects on other value-transforms and value-relationships. In effect, this is where we need to do careful cross-maps between Revenue Streams, Customer Relations and Value Proposition, in order to minimise risks of ‘unexpected’ customer-churn or anticlient-issues that could damage the viability of the business-model.

For an existing business, the key point, as above, is to map out non just the monetary flows but all of the non-monetary value-streams and transforms, including – for this BMC block – the ‘revenue-streams’ or returned-value for those value-flows. Remember that not all value-flows can be converted to monetary form, and that many of the transforms are non-linear and/or non-reversible:

- non-linear: the conversion, where possible at all, does not follow a simple direct formula or algorithm – for example, the same change in one type of value may at different times give rise to completely different changes in another related value-type

- non-reversible: a conversion is possible from one value-type to another, but not the other way round – or cannot be used as a predictor for the reverse-transform

An example of a non-reversible transform is the common strategic error of “our strategy is last-year +10%”: in many (most?) business-contexts, past monetary profits cannot be used as a guide as to what to change in a business-process. Only in the very simplest of business-models would an increase of 10% in all activities lead to a 10% increase in profit: even the classic distinction between fixed-costs and variable-costs should warn us of this, whilst the complexities of establishing and maintaining a market and market-relationships (amongst many other factors) mean that “last-year +10%” is essentially no more than a random guess – and usually a literally-unhelpful guess at that.

For NGOs, government and other non-profits, the same applies, but even more so: most of the value-flows and revenue-streams will not be either in monetary form, or meaningfully convertible to monetary form. Cross-mapping between value-flows, revenue-streams and value-returns to the various Beneficiary stakeholder-groups becomes essential if the business-model is to be describable in any viable form.

That completes this part of the review, for the ‘front-end’ or customer-facing sections of the business-model. Part 3 will explore the ‘back-end’ or value-creation side of the business-model.

And yes, I do know that this has been very long, even by my standards – but I hope it’s been useful? Over to you for comments and suggestions, anyway.

Awesome analysis, I´m finishing my MBA in ESADE Barcelona, And

they´ve been rambling about the BMC all year; and I also felt something was missing, but reading your work I learned that there’s a lot missing, I’m not an expert; actually I´m a dentist, yet I found your defense of Values and non-tangible value transactions very admirable and refreshing.

Congratulations !!

P.S. I bought your e-book

Many thanks for this, Xabier – I’m very grateful to know that my work has been useful to you! 🙂

(Also, of course, thanks for buying the book – though I’m more interested to know that what is in the book helps you in your work!)

No problem, thanks for asking, As I told you, I am no expert; but, Here it goes 😉

I found your website looking for an alternate explanation for the BM canvass.

I thought the book’s explanations were excellent to start to get a grip on the subject but soon you notice its too generic and oversimplified. It´s Ideal for a business presentation or pitch but when using it to work out business plan it felt weak ( a well-marketed, “make a hard job look simple book”).

Your Enterprise Canvas is designed as a Jiminy Cricket, always chirping in your ear, and in every step: think about values, think about the patient journey, think and protect your client´s/partners interests as well as yours, not all value and transactions are money, think about all the relationship around and within the enterprise, and so on.

In short, by adding clear directives, every block in the canvass gains in congruence with each other.

So thank you, again.

Xabier

Some corrections on my last post:

No problem, thanks for asking, As I told you, I am no expert; but, Here it goes

I found your website looking for an alternate explanation for the BM canvass.

I thought the BM canvass book’s explanations were excellent as a start to get a grip on the subject, but soon you notice its too generic and oversimplified. It´s Ideal for a business presentation or pitch but when using it to work out business plan it felt weak ( a well-marketed, “make a hard job look simple book”).

Your Enterprise Canvass is designed to include a Jiminy Cricket, always chirping in your ear, and in every step: “think about values”, “think about the patient journey”, “think and protect your client´s/partners interests as well as yours”, “not all value and transactions are money”, “think about all the relationship around and within the enterprise”, and so on.

In short, by adding clear directives, every block in the canvass gains in congruence with each other.

So thank you, again.

Xabier