Models and reasoning-processes in enterprise-architecture

Just how should we use models and frameworks in enterprise-architectures – particularly in the exploratory phases of architecture-development? What’s the best way to use them? And how do we prevent the frameworks from constraining our options in those processes?

These were questions that came up for me in reading Nick Malik‘s post ‘The purpose of an enterprise-architecture framework‘. It’s a follow-on from his previous post ‘What makes models interesting‘, where he explained how and why he’d responded to the many suggestions he’d received for amending his Enterprise Business Motivation Model (EBMM), and where that had lead his own thinking on how such base-type models worked.

What triggered his new post, he said, was something that I’d put out on Twitter, and that I’ll admit I hadn’t even remembered I’d done. I’d wanted to retweet a response from Richard Veryard to Nick’s initial post:

- richardveryard: #entarch @tetradian @manielse @nickmalik implies purpose of model is to answer specific set of questions – support a given reasoning process

But to fit within Twitter’s 140-character constraint, I edited it down a bit:

- tetradian: @richardveryard “implies purpose of model is to … support a given reasoning process” – yes, agreed / @manielse @nickmalik #entarch

Judging by what happened next, it turns out to have been a nicely-serendipitous accident! – go read Nick’s ‘purpose’-post to see why… 🙂

[There’s an interesting side-point that comes up in that, though. Right at the end of the post, Nick ponders about who to credit for the idea: in the end, he decides it’s mainly an outcome of social-media interaction – and I’d strongly agree with him in that. To me, though, I’d interpret it more as another variant on Bohm-type ‘dialogue’, the way in which ideas arise and develop from the interactions between participants in a conversation, rather than from any specific participant as such. Which in turn means that notions of personal ‘possession’ of ideas are often questionable at best – so much so that, to be blunt, many forms of purported ‘intellectual-property’ are essentially a fraud held together by wishful-thinking, lawyer’s bluff, life-theft, and flagrant dishonesty. Not exactly a wise basis for the so-called ‘knowledge-economy’, perhaps? 😐 ]

In his post, Nick indicated four possible reasons for using a model:

- We want to guide thought in ourselves.

- We want to guide thought in others.

- We want to answer a question asked of us.

- We want to examine the results of asking a question that we find particularly interesting.

I’ll quote Nick’s next section in full, because it’s important for what happens next:

The idea of “supporting a reasoning process” is clearly the first two bullets. We want to guide thought. We are walking through a reasoning process, either for our own decisions or for the decisions we will lead others to (sometimes both at once).

Tom’s edit takes on new ground because he allows us to draw a meta-conclusion: that ultimately a model may lead us to a reasoning process when we were not actually planning for it to. This is the fourth bullet above, and one that I wasn’t really considering when I wrote the post. What if we don’t know where the model will lead, until we create the model? What if we are simply modeling because doing so is literally a form of reasoning in itself? What if we can ask questions of the model that we didn’t think were relevant and wouldn’t have bothered asking, but can only ask because we have the model to answer it?

These are all good points, and in most ways I agree strongly with them. Yet there are two things that I also get from this extension. One is that none of it resolves the third bullet-point, “We want to answer a question asked of us.” And yet, in enterprise-architecture, that’s usually the reason why we’d have started the modelling-process in the first place: we want to answer a question that some stakeholder has asked of us. The other bullet-points arise from that requirement: and we need to keep that point in mind at all times.

The other thing is that to me there’s a bullet-point missing, and potentially the most important point of all, for this context:

- We may need to elicit questions that we didn’t know were there, that can help us answer the core question(s) with which we started.

In other words, loosening off some of the constraints imposed by our assumptions around that initial question, or by a model or framework that we use to help us answer that question.

Nick continues, though, first with a really useful distinction between model and framework:

An architectural framework is composed of a reference model describing the essential elements of a system, and a series of methods for building instance models within that reference model. In other words, a framework is a model and the tools to use it to build more models.

Yet this is where I’m somewhat forced to part company with him, because he starts to go off in a very different direction:

If the purpose of a model is to support a reasoning process, then, by extension, the purpose of a framework is ultimately to support a particular theory of organizational evolution.

Well, yes, fine, interesting and all that – but it doesn’t really help us to answer the initial question. (In terms of Nick’s set of bullet-points above, it’s focussing on the fourth point rather than the all-important third.) And if we go down that path, we create a very high risk of circular-reasoning, where the framework constrains our thinking so much that we can only think in terms of the framework’s built-in assumptions: think of TOGAF, for example, or Archimate, both of which still pretty much force us down an IT-centric track – a disastrous mistake for any whole-of-enterprise architecture.

Instead, I believe that we need to make a clear distinction between frameworks – which, yes, are tightly constrained, and sometimes usefully so – versus metaframeworks – which may appear to be similarly constrained, but actually aren’t, and need not to be. If we assume that Nick’s definition earlier is valid, then the latter are a kind of scaled-up extension of that definition: a metaframework is a reference-framework consisting of one or more core-models, and tools to use these to build contextually-specific frameworks.

Metaframeworks look much the same as frameworks – in fact, at the surface-level, in many cases they are just another form of framework. The key difference is in how we use them – the methods within the metaframework. Instead of using it solely as a reference-framework – in effect, assuming that it’s essentially correct for all contexts – we assume that it’s ‘wrong’: its role is to give enough of a basis – ‘just enough constraint’ – to guide a conversation about whether or why it’s ‘wrong’, and what a contextually-appropriate reference-framework should look like within that context.

In other words, we want to refocus attention on that missing fifth bullet-point: we want to elicit relevant questions that we didn’t know were there, in order to clarify the actual context underlying the initial business-question. Using the metaframework keeps the space open for serendipity and the like, yet also helps to ensure that any questions that arise are relevant to that initial enquiry.

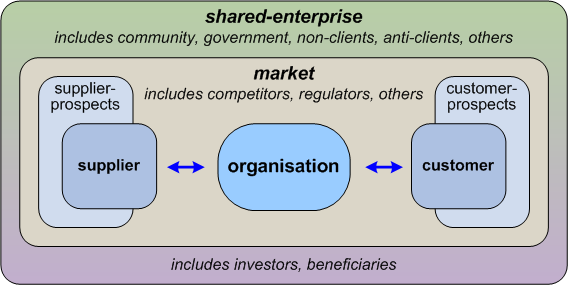

So here’s a concrete example of how that works in practice. A large part of my own work is about building metaframeworks of various kinds – Five Elements, Enterprise Canvas, SCAN and suchlike – and helping colleagues and clients apply them in real everyday architecture- and strategy-development. Over in Central America, my colleague Michael Smith has been making a lot of use of a high-level component in Enterprise Canvas, that I used to describe as the Market Model, and that these days he tends to refer to as a holomap:

In visual form, that model describes and encapsulates four types of relationships with the service-in-focus (‘the organisation’):

- direct actor / direct impact – provider or client (direct service-relationships)

- direct actor / indirect impact – provider’s provider, client’s client (indirect supply-chain relationships)

- indirect actor / direct impact – regulators, analysts, journalists, recruiters, trainers, also competitors (changing the nature of the market-space itself)

- indirect actor / indirect impact – communities, government, non-clients, activists and other anti-clients; also investors, employees’ families etc (defining the nature of the overall ecosystem within which the organisation operates)

Those relationship-types are a bit abstract, and to make sense of them in practice, we need to instantiate them. The metaframework kind of hides that abstraction, yet in a form that provides a concrete guide for conversation about the nature of the context-space – the reasoning-processes that Nick talks about in his post.

Working our way through the ‘domains’ of the visual model, we describe the ‘standard’ way of identifying each of the different types of stakeholders. And we then ask what should be an obvious question, yet one that we don’t usually see in conventional frameworks: “what’s missing?”

- What should be different?

- What should we change?

- What should we perhaps add, or delete?

- How could we describe the relationships between stakeholders in a better way, to highlight distinctions that are important here?

Bouncing back and forth between these kinds of questions, and modelling what those relationships look like in real-world practice, we change the model itself, iteration by iteration, until we arrive at a description of the context that makes sense to that client – which, almost invariably, will be somewhat different from that created by just about any other client, often in quite important ways.

[They learn a lot from the process – but so do we, of course. Some of our best modelling-insights – ones that we’ve been able to reframe and rework into other metaframeworks – have arisen directly from the serendipity that’s kind of designed-in to this intentionally somewhat-‘chaotic’, unpredictable way of working]

Importantly, each client also gains a sense of ownership of and commitment to the resultant model – not least because in many ways they’ve literally made it their own. Here’s a real example, from one of Michael’s clients:

In this case, they’d added two new domains to the model, to emphasise themes that were of significant concern to them: competitors (within the market-space), and anticlients (further-out in the overall business-ecosystem). Also visible in the photograph is one of the more powerful ways that we’d learnt – from and/or with another client – on how to use this metaframework: using photographs of themselves, as a team, to help identify who within the organisation had responsibility for each of those domains in the business-ecosystem, and thence to highlight potential responsibility-gaps that might need to be covered.

In a way, this type of discovery-process gives a more complete answer to Nick’s conundrum with proposed changes to the EBMM: treat it as a metaframework, not a framework. Expect it to change – but only in its usage, as instantiated as a context-specific framework, and not in itself, as the core metaframework. As with other much-adapted base-frameworks such as Business Model Canvas, the original structure and content should be left untouched, such that it can act as a kind of ‘standard’ that can remain as a constant reference-point for all its users. Once we can agree on that – and only change the core-content slowly and carefully, if at all – it’s then perfectly okay to create locally-hacked versions, to match the local needs.

[From fairly painful first-hand history that occurred some years back on this weblog, I’d strongly suggest that it’s wise to make a clear distinction between the original metaframework and anything derived from it: don’t use the same name for both, as they can be significantly different both in underlying theory and in implemented methods in practice.]

But again, though, throughout all of this we need to keep reminding ourselves of why we started all of these reasoning-processes: We want to answer a question asked of us by our business-stakeholders. We need to keep that initial question as our guiding star, and return and return to it time and time again, in whatever we do with models, frameworks and metaframeworks.

Anyway, over to you: comments, anyone?

I think there is an additional step in the argument, which I hinted at in my second tweet, namely that an #entarch framework represents a theory about what matters – what architects should pay attention to.

https://twitter.com/richardveryard/status/385298966424088576

When Nick talks about theories of organizational evolution, he appears to be assuming the management of evolution to be the primary purpose of enterprise architecture. I agree that this is an excellent reason to do enterprise architecture. But it is perfectly possible that someone might propose an enterprise architecture framework with some other primary purpose in mind, and I guess this might explain some of the proposed additions to his framework. So my formulation is deliberately purpose-agnostic.