Anthropomorphise your applications?

“Don’t anthropomorphise computers – they hate that!” – that was the text of a great graphic I found on Flickr, and that I’ve used in various slidedecks since.

Yet might it actually be a good idea sometimes to do just that – anthropomorphise our applications?

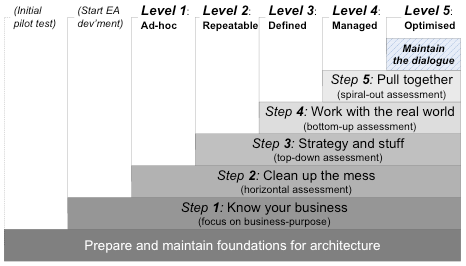

This came up for me today because I’m at last working on the course-outline and content for my upcoming one-day ‘Overview of Enterprise Architecture Techniques‘ tutorial at DED&M (Digital Enterprise Design & Management 2014) in Paris in early February. I’d decided I’ll base the tutorial on my book ‘Doing Enterprise Architecture‘, and in particular the five-step maturity-model that provides the structure for the book:

By the way, this isn’t a strict step-by-step sequence as such: it’s usually a lot more recursive or fractal than that, and we can do work from any of those focus-areas at any time. In practice, though, there is a sort of flow to it, in that we do tend to need to do more of the ‘earlier’ stuff earlier, in order to provide a more robust base for the ‘later’ work – for example, we may well want and need to rush off into top-down design (Step 3) or fixing pain-points (Step 5), but whatever we do there is more likely to be kinda risky and unstable if we haven’t first done at least some of ‘tidying up the mess’ (Step 2).

Anyway, at the same time as brewing on that, I’ve been doing a lot of work on another of my metaframeworks, the Five Elements model – which is equally fractal and recursive, and which, as the name suggests, likewise has a five-part structure to it:

And yeah, since both models do have a five-part structure, I was kinda playing with the idea that they might perhaps line up with each other. Which they do, rather well – with one interesting exception:

- Purpose: aligns well with Step 1, ‘Know your business’

- People: aligns with… ???

- Preparation: aligns well with Step 3, ‘Strategy and stuff’

- Process: aligns fairly well with Step 4, ‘Work with the real world’ – especially if we view both in terms of real-time emergence

- Performance: aligns fairly well with Step 5, ‘Pull together’ – especially if we view this in terms of looking at performance-issues to help identify the sources for ‘pain-points’

Following that logic, the People phase (the ‘Storming’ phase in the Tuckman ‘Group Dynamics‘ sequence) would seem like it kinda ‘ought to’ line up with Step 2, ‘Clean up the mess’. But it doesn’t.

Or does it?

Hmm…

If we take the approach typified by the now-superseded TOGAF 8.1 – which, to my mind, is actually a pretty good description of how to do a ‘clean up the mess’ exercise in an application-landscape and data-architecture – then no, it wouldn’t make much sense at all. An IT-application or database doesn’t storm and rage and play office-politics like people so often do: instead, to quote one of my favourite silly-movies, Short Circuit, “It’s a machine, Schroeder. It doesn’t get pissed off, it doesn’t get happy, it doesn’t get sad, it doesn’t laugh at your jokes, it just runs programs!” True, sure, obviously, of course – or ‘of course not’, perhaps.

And yet, and yet… well, actually, they kinda do, don’t they?

Especially when the application-landscape is in the kind of mess that we so often see at the early stages of an EA development…

And when we look a bit more closely at what goes on in the ‘Storming’ phase of the Tuckman sequence, it kinda makes even more sense again. The purpose of that phase is two-fold: find out what capabilities you have; and then, given those capabilities, work out who’s going to do what – who will be responsible for what, and accountable to everyone else for doing it. The actual ‘storming’ bit comes up mostly when people clash about respective responsibilities: some people demanding exclusive responsibility or ‘rights’ to do something; other people demanding that they should take priority over others, or are ‘more important’ than others; or busy avoiding responsibility for something, often leaving a glaring gap in capability or responsibility that no-one is covering. And so on, and so on: all the usual fun-and-games there…

Yet isn’t that exactly what we have to deal with when we clean up an application-landscape? It’s exactly the same kind of questions: what are the capabilities that we have and/or that we need, who or what is responsible for whatever-it-is happening, what’s the single-source-of-truth, what are the clashes, what are the gaps – it’s all the same. And whilst the applications themselves may not have real egos to flash around, the application-owners most certainly do…

Hmm…

So what happens if we do anthropomorphise our applications? – view them as if they’re ‘people’ in their own right, who have to be led through this ‘Storming’ phase before we can get to a more useful ‘Norming’?

What happens is that, yeah, it can indeed lead us to some quite interesting insights.

For example, what happens if you have two people who both claim to be the sole spokesman for the company, each presenting the company’s annual report to its stakeholders – and yet they give completely-different performance-figures? Yeah, the company would look pretty silly, wouldn’t it? – and you’d have a major fight on your hands straight away, too, almost certainly all the way up to board-level and beyond. But that’s exactly what one of my clients had happen to them a few years ago – except that the ‘spokesmen’ weren’t people, but two different IT-applications, both of which produced a performance-report via different systems and different transforms, but which both happened to have the same name… It was at that point that the idea of ‘single source of truth’ suddenly started to have a great deal of appeal to the executive board!

Yet notice that it’s actually easier to see these kind of traps and system-clashes if we do play this little anthropomorphisation-game, and view the IT-applications as if they’re people – as cranky, unreliable, untrustworthy, over-‘helpful’, overbearing and generally awkward as other ‘people’ are, especially in that ‘Storming’ phase.

Let’s take another example: all those little private spreadsheets and Access-database and sort-of-shared Sharepoint folders that so often turn out to be almost entirely undocumented and unsupported (or unsupportable…) yet absolutely business-critical, and are the bane of any application-architect’s professional-life. Think of those instead as the applications-equivalent of all those kind of invisible ‘glue-people’ that you’ll find quietly hiding away in just about in any large organisation – the people with blurry job-titles and somehow-untraceable reporting-relationships that don’t fit in with the standard hierarchy, but who kinda link everything together and are the glue that link across key parts of the organisation to make things work. In which case, what are the capabilities here? What are they doing? Why are they doing it? – and perhaps especially, what are they doing that can’t be done through the ‘official channels’ and suchlike? If it can’t be done through those channels, why not? What’s missing? What is it that’s in ‘the official channels’ that gets in the way of getting the work done? We’re straight into standard application-architecture at that point – but we got there by viewing the applications ‘as if’ they were ‘people’.

So perhaps play with that idea for a while. Think of your data as if it’s all written down on little scraps of paper, and your applications as people who pick up those scraps from other people, do ‘their own thing’ with those scraps, and then pass the results on to someone else. What are the relationships between all of those ‘people’? Who’s responsible for what, and to whom? What are the clashes? Who does the metaphoric equivalent of spilling coffee all over their scraps, or dumping them in some quietly-forgotten filing-cabinet? (Yeah, that was another real-life case that a colleague had to sort out at one of her clients…) Who does the equivalent of working for a week on some of their scraps of paper, and then throwing the whole lot out and beginning all over with an old version at the start of each working week? (Yep, that’s what we found was happening at one of my clients…) Who does the equivalent of cleaning up other people’s mess, and then gets yelled at for doing it? Gets kinda interesting when you look at it that way… and often painfully-enlightening, too…

Oh, and there’s another really nice payoff for this technique: business-continuity and disaster-recovery. If you’ve sat down and worked out out all of those ‘interpersonal’-relationships between each of your applications, and plotted it all out as if all of the data were on scraps of paper, well, then when (not ‘if’…) things do go all pear-shaped on you, when all of the IT-systems go ten feet underwater or whatever, then you already have a proven backup-plan, don’t you? – you can run it all, for a while at least, just with people and pieces of paper. If you can sort out the actual interpersonal ‘storming’ at the time, of course… 🙂

Anyway, over to you: just an idea to play with – a possibly-useful outcome from placing two metaframeworks together in that way, and seeing what doesn’t and does come up from that clash of potential paradigms.

Comments, anyone?

Leave a Reply