Organisation and enterprise

What is an enterprise? Perhaps more specifically, what is ‘the enterprise’ in enterprise-architecture?

(Quick TL;DR summary: in enterprise-architecture, ‘the enterprise’ is not the same as ‘the organisation’, and is always larger in scope than just ‘the organisation’. Confusing those two terms, or treating them as if they are the same, will cause architectural failure. The reasons for this are explained in some detail below.)

This is somewhat of an old perennial – I’ve covered it in many previous posts, in various different ways. But it’s so important, and there are so many people still making the same mistakes about it, that we really do need to cover it yet again.

There’s been a bit of a Twitter-fest about this in the past few days, again from various different angles. But perhaps the best illustration is this typically-wry aside from Ric Phillips, about current Australian politics:

- RT @ricphillips: Turnbull burns down community TV. Obviously the LNP think the only legitimate sphere of any human endeavour is for-profit companies. #auspol

(For those who don’t know Australia, the LNP (Liberal and National Party) controls the current government there, and is roughly the equivalent of the Republicans in the US, or the Conservatives in the UK.)

I’ll avoid any comments on the politics as such, but just note this one part of the Tweet: “[they] think the only legitimate sphere of any human endeavour is for-profit companies”. Which, if we stop to think about it for even a single moment, would be clearly absurd: there are many other forms of human endeavour than solely for-profit in for-profit companies – raising our families, just to give one example. If someone does think that the only legitimate sphere of human endeavour is for-profit companies, they’d be committing a term-hijack that would be so egregious – so disruptive, in so many social forms – as to be truly obscene.

The key here, though, is that there are two fundamentally different definitions of ‘enterprise’:

- Definition E1: “an endeavour, a bold undertaking” – hence the linkage to the concept of ‘entrepreneur’

- Definition E2: “a large organisation or consortium” – usually for-profit

These two definitions are not the same: don’t mix them up!

What’s too often happened – as indicated in that tweet above about “the only legitimate sphere of any human endeavour is for-profit companies” – is that the two definitions of ‘enterprise’ have been conflated together, with the priority given to Definition E2. They are not the same: that point is really important for enterprise-architecture (and much, much more) – and a point that needs to be hammered home at every appropriate opportunity.

What I want to reiterate here is that whilst both definitions are each arguably valid in their own right, Definition E1 is the only one that should be used in enterprise-architecture. Definition E2 is not ‘wrong’ as such, but in practice it’s so misleading that it should not be used.

Which is not going to be easy, because at present, Definition E2 is the one that is most (mis)used throughout almost all current enterprise-architecture and elsewhere. Usage of Definition E1 is, unfortunately, still relatively rare, and few people seem to fully understand either its full implications for EA practice, or why it is so essential to use this definition rather than Definition E2.

The reason this is so important is that if we use Definition E2, it becomes almost impossible to describe the context in which that Definition-E2 ‘enterprise’ operates – its business-model and so on, and also key business-concerns such as ‘right-sourcing’ – or even the actual motivations and drivers that apply to this Definition-E2 ‘enterprise’. By contrast, if we are systematic in the way we use Definition E1, all of those themes start to make practical sense, and are much, much easier to describe to others across that enterprise.

In enterprise-architecture, we’re working with two distinct types of bounded-entities, that can look the same, and whose boundaries can coincide, but yet have fundamentally different boundaries and drivers:

- Structure S1: a motivational entity, bounded by purpose, values and principles

- Structure S2: an organisational entity, bounded by rules, roles and responsibilities

Again, even though the boundaries of these two types of entities can coincide, they are not the same: don’t mix them up!

In essence:

- Definition E1 – ‘a bold endeavour’ – aligns with Structure S1 – ‘a motivational entity’

- Definition E2 – ‘an organisation or consortium’ – aligns with Structure S2 – ‘an organisational entity’.

- An organisation (S2) is a structure – a means – to support the motivation and intent (S1) of the endeavour (E1) – the ends.

Another useful way to clarify those distinctions is to reframe that S1/E1 pairing – a motivation-based construct, to identify a purposive ‘bold undertaking’ – as an assertion that an enterprise is an ecosystem with a purpose. By contrast, the S2/E2 pairing is more like the kind of ecosystem we find in the natural world, without an intrinsic purpose – other than solely its own survival, perhaps.

When we use Definition E2 for ‘the enterprise’ – as a substitute for E1 – the effective result is a conflation of E2=S1=S2: ‘the organisation is itself the sole purpose for the existence of the organisation’. If we do that, what we’re in effect saying is that the structures that we use to support the endeavour are themselves the purpose of all activity – in other words, that the means are themselves the only ends for activity. Even a few moments’ thought about the differences between ends and means should indicate that, architecturally speaking, conflating all those items together in that way is not a good idea. Ends and means are not the same: don’t mix them up!

(Update, 24Sep14: The following quote, from an article by Allan Little about the Scottish independence-referendum, on the BBC website, illustrates well the complexity of ‘enterprise’ as a term – its boundedness, the nature of its boundedness, its relationship with purpose, and so on. Don’t worry much about the detailed-content here: just note the implied meaning of ‘enterprise’ in this context.)

[In the early 20th century] Even in our remote little village, which seemed impossibly distant even from Glasgow, was connected intimately to the great wide world through the shared global enterprise of the British Empire. …

Empire, industry, world war, welfare state: those were the powerful things that locked Scotland into the Union, that gave generations of Scottish people a sense of partnership in a common purpose.

(Update, continued: Note how the S1/E1 and S2/E2 pairings – ‘bold endeavour bounded by purpose, values and commitments’ and ‘organisation or consortium bounded by rules, roles and responsibilities’ – both make sense in this context. By contrast, the E2:S1:s2 conflation – ‘a large commercial for-profit organisation’ – sort-of makes sense in a strangely-squeezed sort of way, and might be the only way that many business-folk would see it, yet seriously misses the “intimate” emotive drives behind “the shared global enterprise of the British Empire” of that time.)

Given those entities and their boundaries, what or who determines their respective boundaries? Short-answer: we do! The boundaries are fractal: hence, much as with the boundary of a service, the boundary of ‘the organisation’ or ‘the enterprise’ is something that we choose. (We may be told or required to work with specific boundaries for any particular architectural task, but they’re still someone’s choice.)

- The boundary of the enterprise (S1) – its purpose, values and principles – is what we identify it to be.

- The boundary of the organisation (S2) – its rules, roles and responsibilities and its ‘boundary of control‘ – is what we identify it to be.

In practice, we always develop an architecture for an organisation of some kind – if only because that’s what probably determines who pays for the work. Again, though, it’s fractal:

- organisation as a business-consortium

- organisation as a government department

- organisation as a business-unit

- organisation as a sports-club

- organisation as an application-portfolio

- organisation as a functional cluster – for example, a server-rack

- organisation of a work-team

- organisation at a cellular level

We can do an architecture for any one of those things, or any other ‘thing’ that could be considered as bounded by a set of rules, roles and responsibilities.

Yet to develop that architecture, we need to know its context, and the drivers for that context – in other words, in terms of those definitions above, the enterprise that we identify as that organisation’s context, bounded by vision, values and commitments.

We develop an architecture for an organisation, but about the enterprise that we choose to identify as its context.

If we say that ‘the enterprise’ is ‘the organisation’, we’d in effect be saying that we’re going to develop an architecture that has no context. Or, to be slightly more pedantic, we’d be assuming that the vision, the values and the guiding-principles that apply in the respective architectural context are identical to and defined exactly by the rules, roles and responsibilities of the respective organisation. Yes, there might be a small number of special-cases where such an assertion might make sense, architecturally-speaking; but for most architectural concerns, such an assertion would make no sense at all. Once again, don’t mix them up!

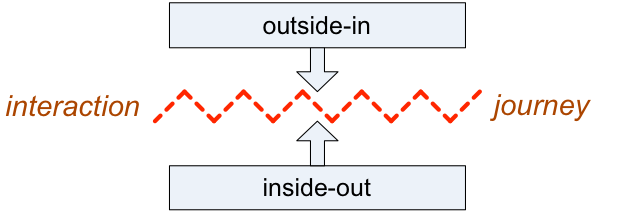

For example, if we don’t separate ‘the organisation’ and ‘the enterprise’, we’d have no means to describe the contextual, and crucial, tensions between ‘inside-out’ (organisation-oriented) and ‘outside-in’ (enterprise-oriented) that drive markets and business-models:

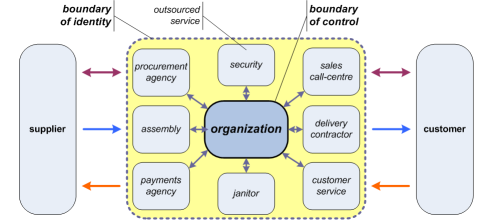

If we can’t separate ‘the organisation’ and ‘the enterprise’, we’d have no means to describe the contextual, yet crucial, differences between a classic ‘hands-off’ sourcing-relationship – where the organisation’s ‘boundary of identity’ and ‘boundary of control’ are the same, and suppliers are outside of both – versus an outsourcing-relationship – where the outsourced-suppliers are outside the organisation’s ‘boundary-of-control’ (‘the organisation’) but inside the organisation’s ‘boundary of identity’ (a specific type of ‘the enterprise’):

And if we can’t distinguish between the current structures (‘the organisation’, as per S2 and E2 above) and its drivers and motivation (‘the enterprise’, as per S1 and E1 above), we’d have no means to make sense of strategy – or even to be able to develop a future-oriented strategy at all.

Or, to put it another way, if we conflate ‘the organisation’ and ‘the enterprise’, what we’d be saying is that our architecture defines an organisation – or something, at any rate… – that:

- is literally self-centric

- has no awareness of its context

- has no means to understand or even identify its market and other ‘external’ stakeholders

- assumes that its own rules must inherently apply everywhere, both within and beyond its own boundaries

- assumes that its top-down rules are the only valid form of motivation

- assumes that its top-down rules are the same as ‘values’

- assumes that its responsibilities to others cease exactly at its own boundaries

- assumes that the present (as defined by existing organisational rules, roles and responsibilities) extends linearly into the future (hence pseudo-strategies such as “Our strategy is last year +10%”)

Otherwise known as ‘not a good idea’… – or not a viable idea in the longer term, at any rate. (Though scarily close to how too many current organisations really do attempt to define themselves and their architectures and ‘strategies’…)

How much of a separation do we need between the boundaries of ‘the organisation’ and of ‘the enterprise’? In practice, for most architectural purposes, a useful guideline is that the enterprise in scope should be able to extend to at least three layers larger than the organisation in scope.

Or, given a scope for which we’re developing an architecture – ‘the organisation’ – we’d typically need to explore a context – ‘the enterprise’ – whose scope extends at least three steps further out.

Let’s see how that works in practice. First, the classic E2 definition, ‘the enterprise is the organisation’:

In other words, architecture-development without any awareness of context: not-a-good-idea, as described above. Or at least, rarely a useful idea.

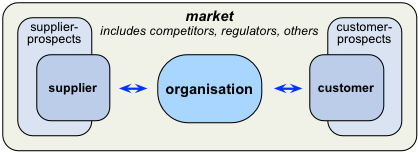

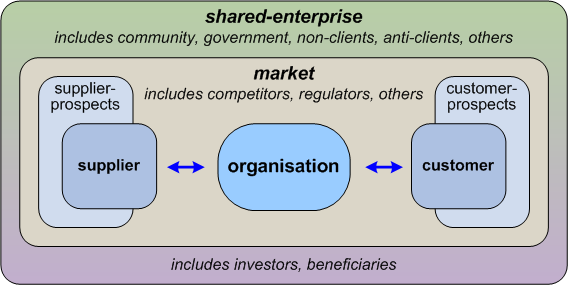

A first layer of separation – for a commercial-business context, for example – would be where we set the boundary of the enterprise to the first-level of the business-model, with the tensions and drivers between the organisation and its direct suppliers and customers:

We can influence across those organisation/enterprise gaps, but we can never ‘control‘ it – not even with the tightest of contracts. That distinction is kinda important…

For some architectural purposes, we might extend that first-level separation to include more of the organisation’s supply-chain or direct value-web:

We’d use this type of extended first-level model to assess architectural, strategic and tactical concerns such as risks within the overall supply-chain. Although there are more connections and interdependencies here, this is still only a first-level separation, architecturally-speaking, because that it still places the organisation at its centre. The model wouldn’t make any sense if we took the organisation out of the picture.

The second layer of separation – if we again use the same commercial-type example – extends the scope of ‘the enterprise’ outward to the market, the context within which a cluster of related business-models take place:

Two important points to note here:

— Although we’ve placed ‘the organisation’ at the centre, this type of model would still make sense if this organisation did not exist. (Hence why we’d typically use this type of model to explore possibilities within a market, above and beyond our existing business-model – or maybe as a potential new business-model.)

— What we’d call ‘the market’ is also a ‘the organisation’ in its own right: it has its own rules, roles and responsibilities. If our ‘the organisation’ wants to be a player in this market, it first needs to know, and be able to align and comply with, those respective rules, roles and responsibilities. (Hence why we’d need to use this type of model to identify the market-context within which our ‘the organisation’ operates, or wants to operate.)

The third layer of separation extends the context-scope further outward to what we might call the shared-enterprise, to include a whole array of other stakeholders who are in effect part of the same overall ‘enterprise-story‘, but who are not active players in the same market-space (layer-2) for the organisation’s business-model (layer-1):

We’d use this type of model for a wide variety of ‘further-reach’ architectural purposes, including:

- identify potential for a market, where no market currently exists

- identify risks and opportunities in community and government, beyond the basic business-model

- create and maintain relationships with investors and beneficiaries – often beyond financial terms alone

- identify, and, where appropriate, build relationships with, relevant non-clients and anti-clients

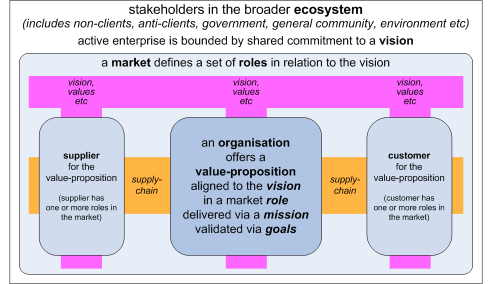

The same E1/S1 pairing of purpose and structure is a key theme behind the Enterprise Canvas model-type, for service-oriented, fractal-based whole-of-enterprise architectures:

By contrast, the E2:S1:S2 conflation – ‘the organisation is itself the sole purpose for the existence of the organisation and its enterprise’ – tends to lead directly to the inherently-dysfunctional, past-oriented Taylorist or Milton Friedman-type concept of the organisation, where the only ‘purpose’ of the entire enterprise is parasitic profit for its financial-shareholders:

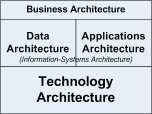

It’s important to note that this structure of ‘enterprise-in-scope is three layers larger the organisation-in-scope’ is a fractal pattern, and hence one we’d expect to see being used to identify contexts throughout enterprise-architecture and many other types of architectures. Which, in practice, we do. For example, back in mainstream IT-oriented ‘enterprise’-architectures, the misleading E2:S1:S2 definition (‘the organisation is the enterprise is the organisation’) is all too common, yet we still see a variant of the ‘self plus two-layer’ model in the ‘three architectures’ framing used in TOGAF and elsewhere:

This model is often referred to as the ‘BDAT stack’ – Business, Data, Applications, Technology. For that context usage, the effective mappings are:

- Technology Architecture: ‘the organisation’; also layer-0 enterprise, ‘the enterprise = the organisation’

- Data Architecture and Applications Architecture: layer-1 enterprise (‘supplier/customer’ type enterprise)

- Business Architecture: somewhat-blurry mix of layer-2 enterprise (‘market’-type relationships, imposed rules, strategic-drivers etc) and layer-3 enterprise (‘beyond-market’-type relationships) – overall sometimes described as “anything not-IT that might affect IT” (i.e. ‘IT’ as ‘the organisation’)

The catch – and which is all too often missed in mainstream ‘enterprise’-architecture – is that the layering only works one way round, where ‘the enterprise’ is larger in scope than ‘the organisation’. Whatever it is that we’re developing an architecture for must be at the base of the respective ‘stack’, as ‘the organisation’: it doesn’t work the other way round. If we do try to run it back-to-front or upside-down – such as in trying to use the BDAT stack to develop a business-architecture – the structures and drivers for the inner layers (‘Technology Architecture’ and ‘Data Architecture’ and/or ‘Application Architecture’) are used as the drivers for the outer layers (‘Business Architecture’, in this case), leading directly to strategic and structural mistakes such as IT-centrism. The layers and their relationships have distinct roles and functions in an architecture, and playing random mix-and-match between them is not a good idea… – don’t mix them up!

Obviously, there are interactions between the layers: that’s the whole point of the BDAT stack and suchlike, to model how ‘bottom-up’ flows and drivers interact with ‘top-down’ and ‘sideways-in’ flows and drivers. But it’s essential to remember that, for those purposes, when using that type of ‘organisation and enterprise’ framing, that for which we’re developing the architecture is always at the base of the stack. For example, if we want to develop a business-architecture, then ‘the business’ is at the base of the stack – not at the top, as in implied in that BDAT stack.

There’s also that key distinction between influence, and ‘control’. We can perhaps influence what happens beyond that base-level, but we probably can’t design it, and we certainly can’t control it – because it’s beyond the rules, roles and responsibilities of ‘the organisation’ that’s at the base of that stack. Control and influence are not the same: don’t mix them up!

Another way to frame all of this is via an extension of the ‘inside-out versus outside-in’ relationships:

It’s another view into the same sort of ‘organisation versus enterprise’ separation, but mapped in a somewhat different way:

- outside-out: the broader-enterprise in its own terms, regardless of whether or not the organisation exists

- outside-in: interface between enterprise and organisation, from the perspective of the broader-enterprise

- interaction-journey: interactions across the interface between the organisation and the broader enterprise – such as through an API or a sales-channel

- inside-out: interface between organisation and enterprise, from the perspective of the organisation (‘black-box’ view of outward-facing interface)

- inside-in: ‘white-box’ view of the internals of the organisation’s services, independent of anything else

This type of mapping between organisation and enterprise is especially useful at the two extremes: making sense of that more outward layer-3 shared-enterprise (outside-out); and doing a ‘clean up the mess’ internal-refresh that, by intent, should not change any outward-facing interfaces (inside-in) – such as per TOGAF 8 technology-architecture refresh.

To complement these two themes – enterprise as motivation, and bounded-entities – we also need to note that the term ‘vision’ has (at least) two fundamentally-different definitions:

- Definition V1: ‘the permanent anchor for all decisions on quality and purpose’ – one of the crucial points being that it does not change

- Definition V2: ‘the end-point for current strategic or tactical intent’ – which does change with each change in strategy or tactics

Definition V1 is typically used in quality-systems and the like, such as in ISO9000:2000; Definition V2 is used in quite a few business-oriented frameworks such as Business Motivation Model. Both of these definitions are useful in enterprise-architecture, but they’re not the same: don’t mix them up!

Both definitions describe motivation or ‘ends’ for an organisation and/or broader-enterprise. The fundamental difference is that a ‘vision’ in Definition V1 sense does not change – in fact, if it does change, we’re no longer in the same enterprise – whereas ‘vision’ in the Definition V2 sense can change at any time, usually dependent on the respective need within the organisation alone. In that sense:

- Definition V1 aligns strongly with the E1/S1 enterprise-pairing

- Definition V2 aligns more with the E2/S2 organisation-pairing

Importantly, the values and principles that arise from a V1-type ‘vision’ apply to all players in the respective shared-enterprise – all the way out to layer-3 and beyond. This means that, whether it likes it or not, the organisation and its performance will be assessed and measured according to that vision – not necessarily its own ‘vision’. Failing to understand this point is what causes businesses to collapse through ‘unexpected’ anticlient interactions. (I’ve seen at least one real-world case where the respective anticlient was virtually the entirety of a whole country, including its government.) This is yet another reason why the E2 definition of ‘enterprise’ should not be used in enterprise-architecture and the like: conflating ‘the enterprise’ into ‘the organisation’ all but guarantees failure to understand this point about the primacy of broader-scope layers of ‘enterprise’.

By contrast, a V2-type ‘vision’ is the kind of motivational-entity that we’d use when describing the intended outcome of an architectural roadmap or the like – such as in the somewhat-misleading concept of ‘future-state’. In enterprise-architecture, the values and principles that arise from a V2-type ‘vision’ are typically design-principles, such as weightings for an architectural trade-off such as ‘build versus buy’.

A V1-type enterprise-vision is crucially important because it underpins the ‘value’-component of any ‘value-proposition‘ in a business-model. In Enterprise Canvas, for example, we model value-flow ‘horizontally’, through the direct relationships between services; yet each of those services also connect ‘vertically’ to the shared-enterprise via the shared-vision and values that define and delimit that shared-enterprise. That’s ultimately the ‘why‘ for any interaction between the organisation and its ‘external’ stakeholders. This means that the full set of relationships between transactors in a supply-chain market-relationship would actually look more like this:

It’s also important to note that every person – and hence, ultimately, every potential-supplier and potential-customer – is ‘in’ not just this one shared-enterprise as delimited by this specific vision, values and commitments to which our organisation aligns itself, but rather is ‘in’ a fractal-type structure of many-upon-many enterprises-of-enterprises, and markets-of-markets, all at the same time. In effect, and in practice, they intersect with specific shared-enterprises, according to the need, often from moment to moment.

It may well be that to us, as enterprise-architects or business-architects or whatever, the organisation is ‘the centre’ of everything; but to suppliers and clients, to the market, and to the broader shared-enterprise, all we ever are is one possible option within the shared enterprise, that purports to propose a means of delivering value in terms of that shared-enterprise. We’re not the centre of their world: and we never are – other than perhaps in certain specific moments where some form of interaction actually takes place. We forget that fact at our peril…

Once again, organisation and enterprise are not the same – so don’t mix them up!

Leave it at that, I guess: over to you for comments, perhaps?

Tom,

The social boundaries depend on the processes of identity creation. Identities can be constructed in many ways but as long they are kept, they form boundaries. There is interaction with other social entities, that part of the environment that both in businesses and in ecosystems can be called “niche”. Both set of processes, those that constitute the identity and those specifying the structural coupling with external environment (incl. both both autonomous and non-autonomous ones), are circular, and interdependent. From one side, you description of an enterprise, resembles a niche, but then there won’t be any pre-set purpose. From another side, if an enterprise is an endeavour, then that would probably form an identity but won’t share purpose with other identities or, at least, I don’t know how would that be.

No quick reply possible on this one, Ivo – it’ll take me some while (and several re-reads, and almost certainly some help from you as well) before I’m able to understand what you mean here.

I have a sort-of half-sense of what you’re saying above, but I’m almost certainly wrong in my guesses. The only thing I do understand is that you’re making some important points there, for which I’m not as yet competent really to make any comment at all. The difference between us is that you have far more knowledge than I have about those kinds of constructs – and that fact really shows in my inability to give a meaningful response to this right now.

Help? 🙂

Tom writes:

“‘the enterprise’ is not the same as ‘the organisation’”

I absolutely agree.

“and is always larger in scope than just ‘the organisation’”

I absolutely disagree. An enterprise may be undertaken by a relatively small part of an organization, and its environmental context may be some other part of the organization. The two parts together need not be larger than the entire organization. An internally focused enterprise, for example (are you assuming that an enterprise must be externally focused?), may have an “external context” that is wholly within the containing organization.

len.

@Len: “An enterprise may be undertaken by a relatively small part of an organization, and its environmental context may be some other part of the organization”.

Ah… I fear there may be a misunderstanding here. To restate what is in the post:both ‘the enterprise’ and ‘the organisation’ are fractal, with arbitrarily-chosen boundaries.

‘The organisation’ in the usual colloquial/legal sense (a company, a government-department, a consortium, etc) is only one instance, in fact a special-case. Instead, for the purposes explained here – and I emphasise again, for the purposes here – ‘the organisation’ is any construct, bounded by rules, roles and responsibilities, that we want to work on in enterprise-architecture – i.e. for which to develop (some aspect of) an enterprise-architecture, its structures, its story and so on. (Most typically, it’s the boundaries of the responsibilities etc that apply to this task – in other words, the entity for which we are receiving the funds for this work.) This may be any subset and/or superset of ‘the organisation’ in that colloquial sense. The example given in the text above was the domain of IT-infrastructure – typically a subset of a colloquial ‘the organisation’, but in some cases of a broader consortium (such as in standards-work, or in supply-chain architectures).

In short, ‘the organisation’ is – as described above – a shorthand term for the scope, delimited by rules, roles and responsibilities for which we are developing an architecture. It identifies the remit of rules, roles and responsibilities to which a given architecture could apply, via governance, in some applicable combination of ‘control’ and/or influence – in other words, the remit of the respective ‘the organisation’.

To reiterate a statement made in the post, we develop an architecture for a ‘the organisation’, but about the context – ‘the (shared)-enterprise’ – within which that ‘the organisation’ operates. To reiterate an example from above, ‘Business Architecture’ in TOGAF is, in essence, “anything not-IT that might impact on IT-infrastructure”: it is a ‘the enterprise’ that is broader in scope than the respective ‘the organisation’ (IT-infrastructure), but bounded in terms of its impact-relationships to the ‘the organisation’.

In that sense, by definition, a ‘the enterprise’ (the architectural-context) is and must always be equal to or, more usually, broader in scope than the respective ‘the organisation’ (the architectural-focus).

I need to hammer this point home: this is fractal, not linear. Exactly as stated above (several times), the boundaries of ‘the organisation’ and ‘the enterprise’ in scope and context for an architectural task are what we choose them to be – and it makes no practical sense to choose boundaries where the ‘the organisation’ is anything other than a fully-enclosed subset of the respective ‘the enterprise’. Do not get distracted by the colloquial concept of ‘the organisation’: it’s merely one special-case, in exactly the same sense that the Definition-E2 of ‘enterprise’ (‘the organisation is the enterprise’) is merely one special-case – and exactly as misleading, too.

OK, you’ve defined “organization” for the purposes of this discussion in such a way that it must by definition be “smaller” than any enterprise it participates in. I think this concept might be easier for people to understand if you simply accepted the conventional (“colloquial”) understanding of organization as “the whole shebang”, and note that “parts of organizations as colloquially understood may participate in enterprises.”

You can demand all you want that they “not get distracted by the colloquial concept of ‘the organization'”, but that is a bit like a doctor demanding that the patient speak the language of doctors. You are certainly free to do so, but it’s probably not a wise strategy for effectively communicating.

As to your assertion that “it makes no practical sense to choose boundaries where the ‘the organisation’ is anything other than a fully-enclosed subset of the respective ‘the enterprise’”, we’ll have to differ on that. Having people understand what you mean seems to me to be an eminently practical reason for doing so.

We had this same disagreement about “profit” some time back.

len.

@Len: “but that is a bit like a doctor demanding that the patient speak the language of doctors”

Most of this is about architects talking with architects – conceptually, the same as doctors talking with other doctors. The article is – I hope – explicit in making it clear that in most cases we will need to do translation when talking with architecture-clients. But before we do that, we first need to get our own terminology right 0- otherwise we’re just going to get caught up again and again and again in the same old mess…

The blunt fact is that we’re dealing with something that’s inherently fractal, and at present we’re stuck with a disastrous mess of scrambled context-specific/context-dependent terminology where no usage makes sense to all potential architecture-clients, and arbitrarily-selected fractal-scopes are assigned arbitrarily-selected labels from a largely-arbitrary mish-mash of terms (e.g. ‘Business Function’ versus ‘Business Process’ versus ‘Business Capability’ etc). From your comment above, it seems to me that you’re still insisting that we use one arbitrary scope – “the whole shebang”, as you put it – to indicate ‘the organisation’: but if we do that, we then have no means (no terminology) to describe subsets, supersets or intersecting-sets relative to that arbitrary scope – not in any consistent way, at any rate. In other words, your insistence adds nothing useful, in fact largely makes things worse – which, I’d suggest, is precisely why that key point about “organisation as fully-enclosed subset of enterprise” seemingly makes no sense to you.

I have just one answer for you: think fractal, not linear. I’m doing the former; you’re still doing the latter. Again, I’m going to have to be blunt about this: you are still trying to use linear-style terminology in a fractal context – which does not and cannot work.

I accept that probably still haven’t explained this well enough. But I just hope and pray that I can find some way to get this point through to you, and to so many others, too – because until you understand this point, all we’re going to be able to do is argue round in circles. Which would be kinda pointless, yes?

Oh well.

I’ll blog on this in the next few days, anyway.

Tom tells me:

“I have just one answer for you: think fractal, not linear. I’m doing the former; you’re still doing the latter.”

I’m a little confused by this assertion, as I have left a long trail of evidence that clearly demonstrates my belief that both organization and enterprise are fractal (the word I have used is recursive) concepts — an organization comprises multiple smaller organizations, and in turn may be a part of one or more larger organizations, and an enterprise comprises multiple smaller enterprises, and may be a part of one or more larger enterprises.

This suggests to me not that I have changed my mind or never believed these things, but rather that something I have said has been misinterpreted so compellingly as to lead you to abandon what I have reason to believe you know about me.

So let me go back and look at exactly what I wrote and see if I can figure out what’s going on here.

len.

>”From your comment above, it seems to me that you’re still insisting that we use one arbitrary scope – “the whole shebang”, as you put it – to indicate ‘the organisation’”

No, I’m making an observation about how most people, including architects, will likely interpret the word. That says nothing about how I personally interpret the word. As they say in the legal profession, you are “assuming facts not in evidence”.

>”but if we do that, we then have no means (no terminology) to describe subsets, supersets or intersecting-sets relative to that arbitrary scope – not in any consistent way, at any rate.”

I absolutely agree, having made this point many times myself, most often with respect to enterprise.

>”In other words, your insistence adds nothing useful, in fact largely makes things worse

Well, that’s a bit of a pointy stick… Again, my remark was about how your interpretation will likely be resisted by many of your hearers, not an endorsement thereof, never mind an insistence.

>”which, I’d suggest, is precisely why that key point about “organisation as fully-enclosed subset of enterprise” seemingly makes no sense to you.”

Ah, but it does make sense to me, it’s just that I don’t find that sense useful, any more than you apparently find my sense, which I have not explained, useful.

And yes, I owe you an explanation of my sense. Getting it out of my head and into a necessarily linear string of words will requires some thought.

len.

OK, I’ve thought a bit about this, and I think I’ve uncovered a part of the problem.

For me enterprises and organizations are qualitatively different kinds of things. An organization is a real physical thing. An enterprise is a concept. Its existence is intangible — we cannot see an enterprise, in the sense that we can see the organizations that participate in its undertaking; we can only see the effects of its being undertaken in the real world.

As such, enterprises and organizations are incommensurable. It is meaningless to talk about an organization being “smaller” than the enterprise it undertakes. All we can talk about is the many to many relationships between organizations and the enterprises they undertake or participate in. The only meaningful comparison we can make is whether a given “organization” can undertake the entire enterprise, or only part of it.

OK, we agree that organizations are fractal or recursive in structure. But what makes something an organization, such we can sensibly apply that name to it?

When I said “the whole shebang”, I didn’t mean the top level organization. I meant a set of people and resources that can legitimately be called an organization. There are subsets of an organization that are not themselves organizations. They can only be called a part of an organization, because they do not have all the characteristics necessary for a set of people and resources to be called an organization. It is this set of characteristics that is what I meant by “the whole shebang”. Thus a department of an organization is itself an organization. An arbitrary set of three people from that department, one of their desks, two of their chairs, a laptop from someone else in the department, and a ream of paper from the department’s supply room is not an organization. The thing that makes an organization a fractal structure is the fact that a specific pattern repeats itself. The arbitrary collection of people and resources described above does not conform to that pattern. It’s not an organization unless it conforms to the pattern. “Conforming to the pattern” is what I meant by “the whole shebang”.

The scale of an instance of the pattern is completely independent of its role in an enterprise. It may not be able to undertake the entire enterprise, but surely there must be at least one organization (i.e. the organization that comprise all the organizations contributing to or participating in the enterprise) that is in fact capable of undertaking the entire enterprise. Otherwise the enterprise must, by definition, fail, as some part of it is not being undertaken.

This is why I object to your statement that the enterprise

“is always larger in scope than just ‘the organisation’”.

First the idea of “larger in scope” only makes sense when interpreted a certain way, and second, an enterprise cannot be realized except by an organization that is capable of realizing the entire enterprise.

len.

Len (dunno if this will end up in the right place, but it’s in reply to your “Okay, I’ve thought about this…” response on 04Oct14)

First, I’ve taken the liberty of editing your comment to incorporate the one-word correction that you posted (replacing ‘enterprise’ for ‘organization’ in the sentence beginning with “The only meaningful comparison…”), and then deleted the correction-comment. I did this so as to make the intended sense of that quite long comment clear, without relying on a much later correction. I trust this is acceptable to you.

Second, and more important, there’s a very simple response to your doubts about ‘the enterprise is always larger than the organisation’: it’s about the relationship between ‘why’ (enterprise) and ‘how’ (organisation). I’ll do a separate blog-post on this, so it doesn’t get lost down here.

By the way, I wrote at length on this subject in a series of three Open Group Blog posts starting at:

http://blog.opengroup.org/2012/12/04/different-words-mean-different-things-part-1/

len.

@Len: “I wrote at length on this subject…”

Yes, I do know, and do remember. We largely agree on the definition of ‘enterprise’, I think.

The points that this post adds are a) the nature of the difference between ‘organisation’ and ‘enterprise’; b) the use of the term ‘the organisation’ to identify the limits or bounds of the directly-applicable scope (i.e. that for which the client for the architecture-work has direct remit or fiat); c) the pattern of relationship between ‘the organisation’ (applicable scope) and ‘the enterprise’ (scope of impact), with the latter “usually at least three levels larger” than the former; and d) the ‘non-reversibility’ of the pattern (which is why the standard BDAT-stack in TOGAF should not be used for business-architecture, or often even for ‘information-systems architecture’ [Data + Applications]).

Here’s an encouraging little story. In a discussion at work about EA and sustainability, I started, as you would expect from my recent writing, from the question of what is needed to make an organization sustainable. I deliberately said organization, not enterprise and that’s what I meant.

We then looked at what services an organization (in this case our own) might provide and how it did that. We could see immediately a whole range of partners – partners in the sense of other organizations that delivered not merely services to us but services on our behalf to others. I didn’t even have to mention customers – someone else brought that up. So when I explained that therefore this whole collection of loosely coupled organizations and people was really the enterprise, the reaction I got was effectively “tell me something I don’t know”!

I decided to post this before seeing the Tom/Len discussion, so it’s not intended as a comment on that thread. I’m unsure as yet whether it has any bearing on the discussion. The event itself actually predated Tom’s post. My point is that it’s encouraging to see that the idea with which Tom’s post starts is for some people just plain old common sense, if looked at in a context they recognize.

Thanks for sharing that Stuart. It’s encouraging to know that Tom and I (and others) are not just “pi**ing into the wind”.

The question it provokes, though, is if it’s just common sense to some people, why is it such a hard sell to the EA community?

len.

@Len: “if it’s just common sense to some people, why is it such a hard sell to the EA community?”

The short-answer is that ‘the EA community’ still insists on imposing, onto every context, its own arbitrary terminology – such as the BDAT-stack – rather than every actually looking at the context in question. It starts by asserting that this arbitrary terminology is ‘the truth’: “there are three architectures” etc. There is no fractality to it at all, in fact no awareness of the inherent fractality of the contexts within which we work. The result is an active suppression of what is actually a necessary exploration of scope and terminology.

As I put it in an earlier post from a couple of years back, ‘The social construction of process‘, “exploring and answering the question ‘What is the process?’ is itself part of the process”. If we prevent people from exploring from exploring their own context – such as by imposing a linear terminology onto a fractal context – then we and they will not be able to get the results that are needed. If you want to understand why EA is often seen as not delivering value to ‘the business’, one of the key reasons is right there: wrong-headed, arrogant imposition of linear, self-centric terminology into inherently-fractal contexts where it just does not fit.

Stuart’s approach is the right way to do it; imposing a rigid, predefined scope-definition, as in Phases B, C and D in the current TOGAF ADM, is exactly how not to do it. I’ve explained this point over and over for some years now, evidently to deliberately-deaf ears too much of the time: I just wish people in the EA-space would finally get it, that’s all, because doing the right way is the only way that works.

Oh well.

@Stuart: “just plain old common sense, if looked at in a context they recognize”.

Yep, definitely. The catch is to find a way of framing it such that they discover it for themselves – rather than having an external definition imposed upon them.

The only point I’d comment on your example is that it’s still primarily at the transactional level – what I described in the post above as ‘Step 1’. It would be interesting to see what happens when you introduce the idea of ‘the whole market-space’ (a Step-2 enterprise) and, perhaps allow concept of ‘non-transactional stakeholders’ such as families, communities and anticlients to drift into the story (a Step-3 enterprise). If you can steer the conversation in that way, then the fractal nature of ‘the enterprise’ should become more clear – that we need to take different types of ‘the enterprise’ into account if we want to fully understand the impacts on whatever aspect of ‘the organisation’ is our current concern.

As I said in the post, the BDAT-stack (as in TOGAF, Archimate, IAF and so many others) does do this correctly and explicitly for the specific case where the focus of concern is IT-infrastructure; but it breaks down if we try to run the stacking ‘upside-down’ – as in TOGAF’s ‘Business Architecture’ – because we end up with a tiny subset (IT-infrastructure) being treated as as the superset (Step-3 enterprise) – leading directly to the infamous IT-centrism of so much current ‘enterprise’-architecture. The trick there is to recognise the dangers of misusing the ‘stack’, and to guide the discussion and exploration accordingly.

Hi. To Len’s plaintive appeal I have two simple and possibly simplistic observations.

One is that the difference between the “EA community” and my audience is that my lot have relatively few pre-conceived definitions, a desire to engage in new things and a lot of experience from the “real world” that they project onto the enterprise view. They don’t have an “expert” status they feel the need to defend.

The other is that, having a pathological fear of definition wars, I try to let this kind of thing emerge from a discussion of something concrete in as natural a way as possible. It doesn’t always work but when it does, I learn stuff too.