Services and Enterprise Canvas review – 2: Supplier and customer

What is a service-oriented architecture – particularly at a whole-of-enterprise scope? How do we describe relationships between services – particularly in the main value-flows? What happens within those service-interactions?

This is the second in a six-part series on reviewing services and the Enterprise Canvas model-type:

- Core: what a service-oriented architecture is and does

- Supplier and customer: modelling inbound and outbound service-relationships

- Guidance-services: keeping the service on-track to need and purpose

- Layers: how we partition service-descriptions

- Service-content: looking inside the service ‘black-box’

- Exchanges: what passes between services, and why

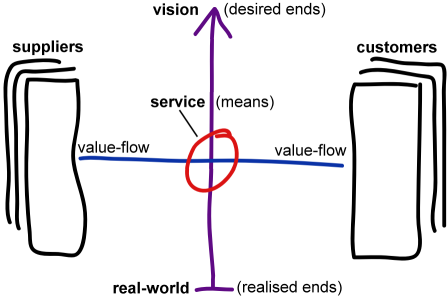

In the previous post in this series, we saw how a service is ‘a means to an end’, and usually sits at an intersection between ‘horizontal’ value-flow and ‘vertical’ intent:

Each service would usually sit within a sea of other services, all exchanging value ‘horizontally’ with each other, to assist each other in reaching towards their respective needs and purpose. To explore that sea of services – the architecture of that sea of interrelationships and interdependencies – we would apply the ‘Start Anywhere’ principle: pick a service – any appropriate service, at any level of abstraction – and start exploring the relationships from there, placing the focus of attention on one service after another as the need and sense suggest.

(In some of the modelling-work I’ve done, the current service-in-focus is referred to as ‘This’.)

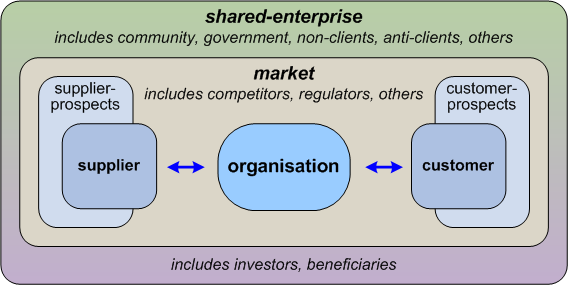

Value-flows may move in any direction between service-pairs, and always have at least some bidirectional component to them. There are emphases or currents in that flow, yes – especially relative to the service-in-focus, the ‘This’ – yet it’s misleading to think only in linear terms such as ‘supply-chain’: the metaphor of a sea or ocean of value-flow is more apt overall. By convention, though, where a flow seems primarily to come from another service, that service is typically referred to as a supplier or service-provider to this service; and where a flow seems primarily to go toward another service, that service is typically referred to as a customer or service-consumer of this service:

(An important aside: note that ‘supplier’ and ‘customer’ are merely roles, not absolutes. A partner, for example, will usually be both ‘supplier’ and ‘customer’ in some sense – sometimes both at the same time, as in co-creation of value.)

As described earlier, a service could be anything at all: in a service-oriented enterprise-architecture, everything in the enterprise either is or represents or implies a service. For simplicity’s sake, though, let’s assert that the service-in-focus here, the current ‘This’, is the overall service implied by the organisation as a whole – ‘Our Company’, ‘Our Government Department’, or whatever. Given that, let’s assign the label ‘the organisation‘ to the current service-in-focus, in the examples that follow.

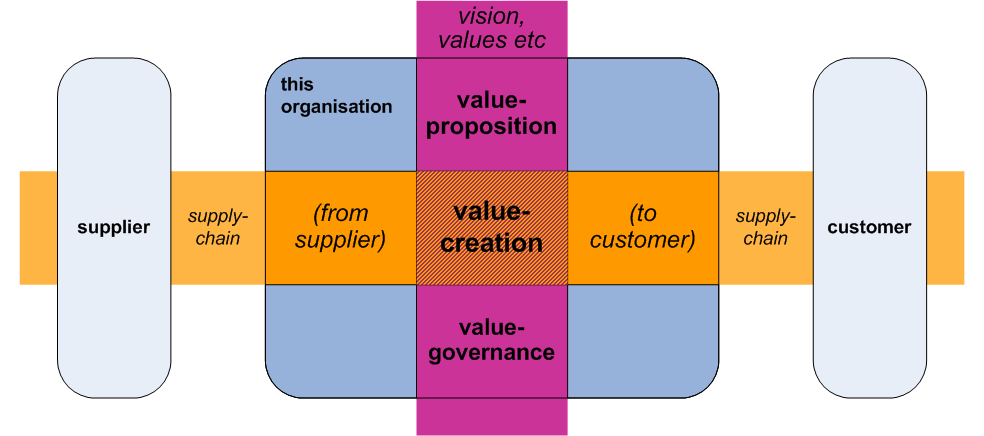

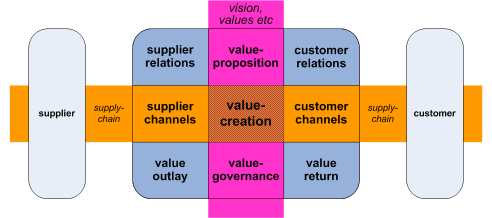

Note, though, that it’s not just about value-flow: every service also intersects with that ‘vertical’ dimension of vision and value – that which determines what value is for the service, the ‘why’ that underpins everything it is and does. Given the capabilities of the service – which we’ll explore in Part 5 of this series – the service connects those capabilities to the ‘why’, to describe how it would add value to the overall value-flow in its service-context: in other words its value-proposition, and its means of value-creation. To these it should also add value-governance, to support value-creation, and to confirm that what it does, does indeed connect back to the original ‘why’:

A crucial point here is that the value-proposition for a service is not (as some have put it) “the fancy name for your products and services” – a bunch of random attributes assigned to some otherwise lacklustre ‘thing’ or action. Instead, it needs to be understood here in its literal sense: ‘value-proposition’ as proposal to deliver value.

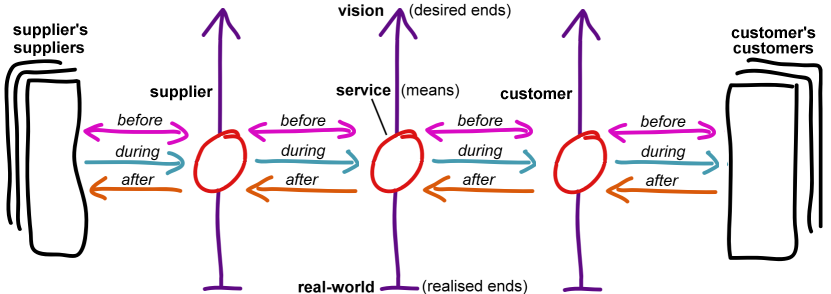

The reason why this point is so important is that this view of ‘value-proposition’ is what links the service – ‘the organisation’, in this example – to the much larger shared-vision shared in some way by all players in the respective market and shared-enterprise, and which thence in turn provides a key unifying-factor and ‘why’ for the ‘horizontal’ value-flow:

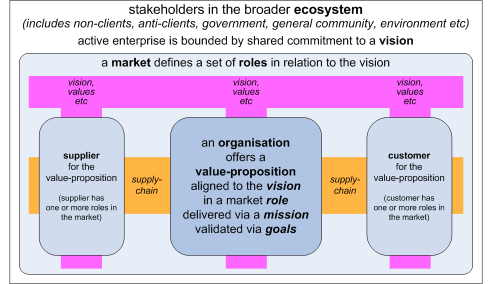

It’s not just that the service-in-focus exists at an intersection between ‘vertical’ values and ‘horizontal’ value-flow, but that this is true for every service – which in turn also drives the ‘why’ for that horizontal value-flow. The connection between a service and its suppliers and customers is not solely through that horizontal direction, but also kind of ‘over the top’, via connection of vision and values. We could summarise this in visual form as follows:

Note that the respective vision and values for each service need not necessarily be the same – in fact in practice it’s probably rare that they are an exact match, and the degree of match will often vary over time anyway with the changes in each player’s needs. Instead, it’s more that, at that specific time and/or for that specific purpose, the match between the respective visions and values is close enough such that the respective value-propositions ‘make sense’, are seen as ‘having mutual value’ for the respective purposes of each of those services.

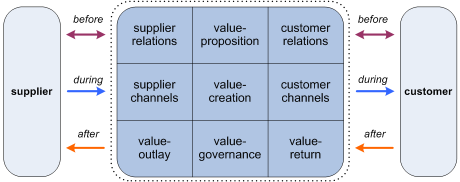

What’s interesting and important, though, is the question about when that interaction around value-proposition takes place. Classic marketing-type models tend to assume that the only requirement is to grab someone’s attention – the almost-literal meaning of ‘advertising’, of course – and that the assorted attributes assigned to the product or service, as ‘value-proposition’, would be enough to establish the grounds for transaction, and thence to execute that transaction – a transaction which, in many market-models is deemed to be complete as soon as the the organisation has been paid. We’ll explore this in more depth later in this series, in Part 6, on inter-service exchanges, but the key reality here is that the core parts of the interactions around value-proposition have little connection with the main transaction itself, but instead are more about establishing mutual reputation, respect and relationship, before the main transaction can takes place. A lot also needs to happen after the transaction nominally completes, too – ensuring that all aspects of the overall interaction are properly closed-off for all parties. Again, we can summarise this visually as follows:

The core part of that interaction-set – the so-called transaction – is, yes, the main part of the horizontal value-flow. The other parts, though – the ‘before‘ and the ‘after‘ – are associated more with that connection via the vertical value-connection, the vision and values and suchlike: and unless that connection is properly established and maintained, either the transaction won’t happen at all (‘before’), and/or won’t be repeated (‘after’). It’s therefore useful to re-do our previous somewhat-over-simplistic description of the horizontal value-flow, so as to emphasise those phase-distinctions:

This also helps to explain more about the distinctions between value-proposition, value-creation and value-governance: respectively, they link the service’s own ‘vertical’ connection more with the before-transaction, during-transaction and after-transaction parts of the horizontal value-flow. And we can then also split the emphases of activities within the service in terms of three different ways they may face:

- inbound – activities to support value-flows mostly coming inward towards this service, from other services in a ‘supplier’ role to this service

- self – activities in what this service does to create, deliver and govern its own value for itself and for others in the shared-enterprise

- outbound – activities to support value-flows mostly going outward from this service, towards other services in a ‘customer’ role to this service

Which, combined with the ‘before’ / ‘during’ / ‘after’ distinctions, gives us a kind of nine-cell matrix of activities within the service, that looks like this:

Or, showing just the ‘child-services’ matrix itself:

To give a more concrete example, we could describe each of these ‘child-services’ – or activity-roles – in terms of common business-activities in a commercial business-organisation:

- inbound:

- supplier-relations – procurement

- supplier-channels – purchasing, inbound-goods

- value-outlay – accounts-payable

- self:

- value-proposition – product/service-development

- value-creation – production, manufacturing

- value-governance – line-management

- outbound:

- customer-relations – marketing

- customer-channels – sales, outbound-goods

- value-return – accounts-receivable

Remember, though, that the same activity-roles apply in some way or other in every service, right the way down to a single line of code in a web-service or suchlike: hence why the more generic labels are useful, to provide a consistent way to describe the same kind of activity-role within any service in any context.

Note again that this applies to every service: every service can be described in the same consistent way, with the same structure of inbound / self / outbound, and before / during / after, and hence the respective equivalents of the same ‘child-services’ in terms of this three-by-three-matrix. With very few exceptions, every service is both a consumer and provider of other services as they flow around that ocean of ‘horizontal’ value-exchange, each service also connecting with others via those ‘vertical’ links of values and purpose, to provide the ‘why‘ for each service-exchange:

Where the services have distinct and, usually, different core-purposes, we’d typically describe this as a supply-chain or value-web. But when they’re linked together via the same purpose, there’s another more common term that might well be used: process. In practice, a process is a sequence of interactions and exchanges between services – a sequence that might be structured or unstructured, exactly-repeatable or barely-repeated at all, yet still conceptually the same thing, just a sequence of service-interactions that, collectively, also look like ‘just another service’.

But because process can in effect be perceived as ‘just another service’, there’s a tendency in some circles to treat process and service as if they’re the same thing. They’re not – or not quite, anyway: the key distinction is this point about process as a sequence of interactions, rather than something that’s inherently self-contained. The real difficulty here is that, in effect, the boundary of a service is what we say it is: so we do need to be careful to define service-boundaries that make consistent sense, whichever way we want to use them.

One last point: all of the above only applies to the service-relationships across the main transaction-oriented flow of value around a shared-enterprise – the main ‘horizontal’ flows. There are also other flows that are needed to support viability and ‘completeness’ in the longer term – or, to quote an earlier post on this theme of ‘completeness’:

we check that the service has all the connections and support and flows that it needs to play its full part in the respective layer of the enterprise value-network.

There are two main groups of these other non-transaction service-relationships:

- guidance – including direction-services, coordination-services and validation-services

- investment – including investors and beneficiaries

These are what we’ll explore in the next part of this series.

Any comments or questions on this so far, though?

Leave a Reply