On value-governance

What do I mean, when I talk about ‘value-governance’ in an enterprise-architecture sense? In Enterprise Canvas, what does that ‘Value Governance’ cell represent? What do its services actually do, for the service, the organisation and the overall enterprise?

This one’s for social-change activist Fernanda Ibarra, and is really a follow-on to various conversations we’ve had around so-called ‘alternative-currencies’.

[My own position is that, although they might be useful in the short-term, ultimately no currency – ‘alternative’ or not – will be anything other than a hindrance in getting us out of the global-scale oncoming economics-storm that’s heading our way Real Soon Now. Some folks – maybe many, if not most – might consider that to be a teensy bit extreme: but there is solid reasoning of both theory and practice behind it. I won’t go into the details here, but you’ll find more, for example, in posts such as ‘Four principles – 3: Money doesn’t matter‘, ‘The architecture of a no-money economy‘ and various of the other posts here on RBP-EA (Really-Big-Picture Enterprise-Architecture) themes.]

Although this is focussed somewhat at the ‘big-picture’ level – the economics of entire communities or countries, right up to a global scale – much of it also applies to the functioning and viability of relationships between ‘organisation’ and ‘enterprise’ at any scale, right down to individual-services level. Or, for that matter, to relationships and services within a family or suchlike.

Okay, so what is ‘value-governance’? To answer that, we’d need to explore what’s meant by its two terms:

- value

- governance

Which is perhaps not as obvious as it might at first seem…

Let’s start with what most people seem to think of as ‘obvious’: money as ‘value’ – the notion that all forms of value can be described monetary terms, therefore money is value, and value is money. If we accept that assumption, then governance of value is, in essence, governance of money – which is the core assumption behind most current so-called ‘economics’.

In a possession-based economy – of which a money-based economy is probably the best-understood sub-type, though barter is another, for example – the natural tendency of the entire economy is that resources automatically trend towards ending up where they’re least needed. This leads, in turn – again, almost automatically – towards at the least an oligarchy, more likely a plutocracy, and quite possibly a full-blown kleptocracy.

In each of those cases – particularly the latter two – the purported purpose of the entire economy is ‘making value’ for the ruling elite: which, when ‘value’ is equated with money, means that the purported ‘the purpose of everything’ is ‘making money’ for that elite of ‘owners’. Hence concepts such as the primacy of ‘shareholder-value’ and the like.

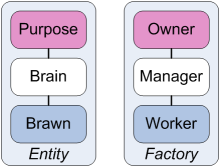

Which, in turn, gives us a concept of ‘value-governance’ or ‘value-management’ guiding a one-way hierarchical flow of value to ‘the owners’:

Which, in turn, gives us the classic Taylorist-style view of ‘management’, both of organisations and entire enterprises, as an intermediary role to govern the extraction of ‘value’, as money, from the overall enterprise, on behalf of the ‘owners’ of that enterprise:

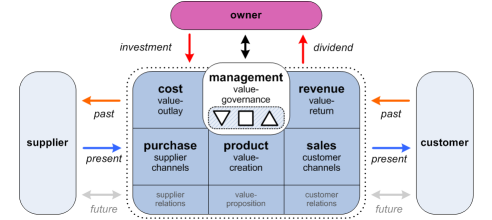

(For now, don’t worry about the triangle- and square-symbols and the past / present / future arrows in that diagram above – we’ll come back to those later.)

All of which is fine – from the perspective of the ‘owners’, anyway – except for one very important point: there are many, many forms of value – and money is a very poor proxy for most of those forms of value. The result is that a money-based or currency-based economy – whatever form of ‘currency’ may be in use to govern exchanges in that economy – is inherently non-viable, especially over the longer term. The only way it can be made to seem ‘viable’ is to run it as a pyramid-game or Ponzi-scheme – which, as soon as it hits up against any kind of non-negotiable limit, always will and must cannibalise on itself, eventually to oblivion.

To make sense of what actually happens in a viable economics – and thence the services and other societal mechanisms that underpin the viability of that economics – we have to start again, pretty much from scratch, with value itself.

Which leads us back to the first part of that first question: what is value?

And the short-answer is: whatever people feel is ‘of value’.

Anything at all – that’s the whole point.

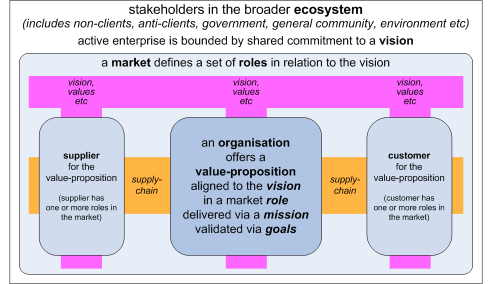

Perhaps the simplest way to summarise this is that a shared-enterprise, of any kind, coalesces around a kind of shared-story (or ‘vision’, or ‘promise’, or whatever other equivalent term is used for this). Another way to put this is that a shared-enterprise is an ecosystem-with-purpose – in contrast to ordinary ecosystems, which generally don’t have a purpose as such (other than perhaps POSIWID). The values (plural) of that enterprise are, in essence its descriptions of success – and, in some ways, of non-success – in terms of that story. Those values are then expressed in practice as principles, guidelines, algorithms and rules (to use SCAN terminology).

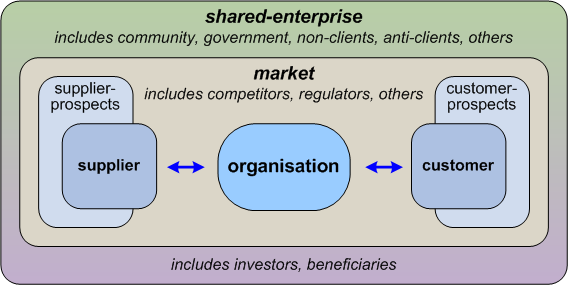

From an organisation’s perspective, it may not realise that it’s inside that shared-story of the shared-enterprise. One of the reasons it may not see that shared-story – and the necessary sharedness of that story – is because its initial view is obscured by the market in which it operates, which in turn is within and encompassed by and guided by the vision and values of that story. We also might note that investors and beneficiaries form only a subset of the seemingly-‘external’ stakeholders in that overall story:

An individual or organisation engages itself – places itself – within that story, by connecting with those values of the shared-enterprise. This then gives a driving reason – a value-proposition – for a service that can assist others in reaching toward their stories, and also often assisted by others, all of which in some way also connect with the same story as that for our own enterprise. Or, summarised in visual form:

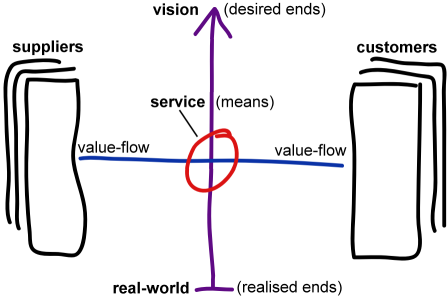

In effect, every service sits at an intersection of values – the ‘vertical’ connection to vision and story – and value-flow through the supply-chain or value-web shared with other services – the ‘horizontal’ flow of assets, and actions upon assets – that makes it possible to enact the aims of that vision or story:

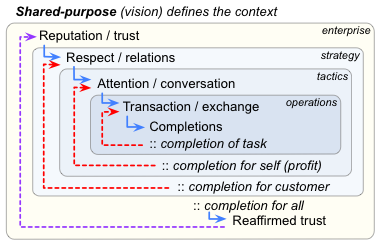

In the conventional Taylorist-type model, all interactions across the supply-chain consist of gaining someone’s attention (marketing), and then enacting a transaction (sales). Value-governance, in this model, consists in ensuring completion of the sale from the organisation’s perspective (accounts-receivable), balancing that up with any payments made to suppliers and others (accounts-payable), and then extracting the difference (profit). It’s pretty straightforward – and easily describable to solely monetary forms of ‘value’:

Notice, though, that’s there’s no real story here: it’s just an interaction between machines – or barely even that, really. It’s what’s called ‘push-marketing’: “I have something to sell, who can I push it at, to get them to buy it from me, such that I can make a profit?” In this view and context, ‘value-proposition’ is, as Steve Blank put it in his article ‘How to build a billion-dollar startup‘, merely “the fancy name for your product or service”.

Which is a dangerously-incomplete view of what actually happens in those interactions. For the transaction to happen, we need the other party’s attention, yes; but before that can happen, we need enough respect and relationship such that they’ll listen to us at all; and before that, there needs to be a reason enough to build that relationship – a reason that, in essence, is based on trust and reputation, which in turn are linked to and assessed in terms of the values of the shared-story.

To make it work – and, in particular, to make it work more than once – each of those distinct needs must be satisfied. Value-governance, in this sense, consists of making sure that all of those needs, of all of those stakeholders in the shared-enterprise, are indeed satisfied:

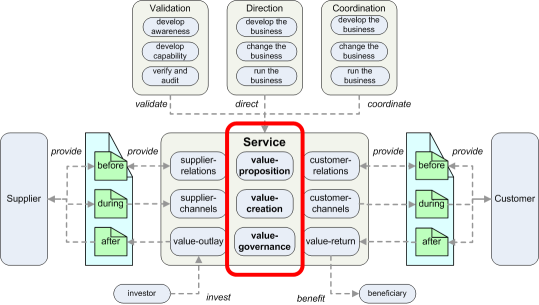

All of this is fractal – interactions and transactions within other interactions and transactions. But if, for simplicity, we think of the ‘attention / transaction’ parts of this cycle as the main focus of what’s happening during what most people would think of as ‘the transaction’, then the main focus of the ‘reputation / relations’ parts takes place more before that ‘the transaction’, and the set of completions-activities happen after that ‘the transaction’. Hence it becomes useful to map those interactions in terms of before, during and after the main-transactions, and symmetrically-so on both the ‘incoming’ side – supplier-facing’ and the ‘outgoing’ side – customer-facing:

Which, when we link all of this together with that view of the shared-enterprise, and expand it out into a bit more detail, gives us something like this – the Enterprise Canvas view of the metaphoric ‘anatomy’ of a service and its interdependencies and stakeholder-relations:

By comparison with which, you’ll note, the classic Taylorist view of an organisation is literally upside-down, back-to-front, dangerously-scrambled and dangerously-incomplete:

Perhaps the most crucial distinction between the two models is that what’s called ‘management’ in the Taylorist model is, in Enterprise Canvas, split apart into a suite of distinct and often necessarily-separate roles – some of which do not belong within the classic management-structures at all. The ‘coordination-services’, for example, by definition sit between service-entities, not within them. The ‘direction-services’, whilst classically ‘management’-type tasks, apply to the whole service-entity, rather than solely within one small self-referential sub-unit of it. And as indicated by their placement in the green ‘values’ area, outside of the service-entity itself, all of these guidance-services both link the service-entity more strongly to the ‘outside-world’, beyond the organisation alone, and also, crucially, link it more strongly to the story and values of the broader shared-enterprise.

Perhaps the key difference here is the role of ‘validation-services’ – a role that, in the Taylorist view, is barely even acknowledged to exist, other than perhaps as an unwanted and unwarranted hindrance to the all-encompassing drive to ‘make money’. Vision and values come from the enterprise-story: the validation-services are the means via which the organisation verifies and assures its connection to the enterprise-story – and hence protects its own reputation and respect, without which the business will die.

In the Enterprise Canvas checklist for service-viability, we need one set of validation-services for each type of value in the enterprise-story. Some of these ‘themes of value’ apply pretty much everywhere, in every organisation and enterprise: health-and-safety, for example, or security, quality, financial-probity, environment, fairness, and so on.

[Note that some of these ‘universals’, such as fairness, may vary considerably from one culture to another – a fact that can be extremely important to organisations and enterprises that bridge across cultural boundaries.]

Other values, and their relative priorities, will be more specific to the enterprise and its story. For example, reliability and efficiency might be extremely important for an energy-utility, but perhaps much less so in a start-up or an experimental research-laboratory, where speed, and speed of learning, might well be more important.

In a somewhat-expanded view of the stereotypic ‘child-services’ within Enterprise Canvas, we see the validation-services split into three ‘child-services’ that cover distinct value-governance roles, guiding the service as a whole:

There’s also a fourth aspect of value-governance, that takes place in real-time service-delivery – which forms part of the function for that Value-Governance cell within the service itself. We can summarise these roles as follows:

- develop awareness – explain and educate as to why the value or quality is important to the enterprise as a whole, and why it needs to be supported [delivered by organisational validation-service]

- develop capability – provide training as to how, when, where and with-what to support that value or quality [delivered by organisational validation-service and/or external training-provider]

- enact capability – enact the training in real-time work [supported in real-time by the Value-Governance child-services with the service itself]

- verify, audit and improve performance – assess performance, and derive and apply lessons-learned for continual improvement [delivered by the Value-Governance child-services, together with organisational validation-service and/or legally-distinct external auditor or service-provider]

Within the organisation, we’d typically see each validation-service as a small distinct business-unit, often sited somewhat outside of the main ‘org-chart’ hierarchy, and often with its quite small dedicated team with what we might call ‘pervasive’ authority: their work applies everywhere, to everyone and everything. Each of these business-units supports a single identifiable and explicit core-principle: Health and Safety supports the principle of ‘people should be safe at work’, Environment supports the principle of ‘sustainable business in the longer-term’, Knowledge Management supports the principle of ‘continual shared-learning’. A Programme Management Office provides similar oversight for whole-of-organisation change, whilst Enterprise Architecture does – or should – provide support for an enterprise-wide principle of ‘things work better when they work together on purpose’. And so on: you can see the underlying idea here, anyway.

Moving on, to value-governance as a cell or ‘child-service’ within the Enterprise Canvas service-model – what does it actually do? For that matter, what is governance in this context?

One thing that should be emphasised here: governance here is not about ‘control’ in the classic Taylorist sense. It’s necessarily a lot more subtle than that – more about influence and guidance than command or demand. In essence, it’s about holding to quality, doing what we need to preserve and enhance quality, in the broadest possible sense: for example, quality within enterprise-architecture itself.

One aspect is the ‘vertical’ connection to the values of the shared-enterprise. In Enterprise Canvas, the archetypic Value-Proposition child-service connects and binds the capabilities of the service into something that might be considered ‘of value’ to other players within the shared-enterprise, and conducts its own conversations with those other players about this, via the Supplier-Relations and Customer-Relations child-services. Once clarity on that has been achieved, the Value-Creation child-service creates something ‘of value’, in terms of that value-proposition, connecting with other players via the Supplier-Channels (incoming) and Customer-Channels (outgoing) child-services. The role of Value-Governance here is to keep all of those on track, connecting the actual results back to the initial intent – all in context of the shared-enterprise values. In short, it keeps track of alignment between value-proposition, value-creation and value-delivery:

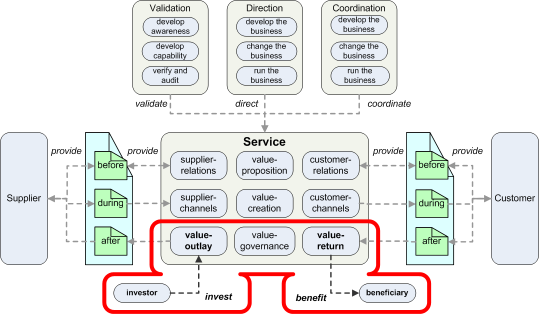

In terms of the ‘horizontal’ connection to value-flow around the shared-enterprise, Value-Governance is also responsible for keeping track of the ‘after’ value-flows – such as, classically, accounts-payable (Value-Return) and accounts-receivable (Value-Outlay), and the balance between all of those flows. The catch, of course, is that these flows of value are not solely in monetary form, and the transforms between those various types of value can be extremely tricky – which is precisely why some active form of governance, linked to the shared-enterprise and its definitions of success, in terms of the enterprise-values, is so essential here:

As also indicated in the Enterprise Canvas checklist-diagram above, Value-Governance also provides guidance, oversight and balancing of the value-flows from Investor-stakeholders, and to Beneficiary-stakeholders. There is, again, a very large catch – or several of them, rather:

- investments may well not be in solely monetary form

- dividends and benefits may not be in solely monetary form

- benefits and dividends may not be in the same forms of value as in the initial investments

- investors and beneficiaries may not be the same people

- many of the transforms between all those various types of value may be non-linear, non-reversible, non-transitive, and in general very hard to describe anyway

All of which is likely to make value-governance very tricky – especially once we break free of the crassly simplistic delusion that ‘money=value’…

One other item, not shown here but indicated as the ‘mgmt-info‘ flow in the main Enterprise Canvas summary-diagram earlier above, is that Value-Governance typically also manages information-flows to and from external child-services that this service integrates and manages. In that sense at least, Value-Governance does somewhat resemble the classic Taylorist-type ‘line-manager’, ‘supervisor’ or ‘foreman’ role – except that, unlike in Taylorism, the role provides a support-type function, not one of ‘control’.

A couple of other points that we should also note. One is the difference in time-emphasis between the internal Value-Governance and the sort-of-external guidance-services:

- the guidance-services are primarily focused on support for future-to-now

- the Value-Governance cell is primarily focused on support for past-to-future

The other point, related to this, is that if the guidance-services become subsumed into Value-Governance as an all-inclusive ‘the Management’ – as in Taylorism and suchlike – the past-to-future becomes collapsed to a short-term self-referential closed-loop: ‘the future’ is viewed solely in terms of, or as, an extension or replication of the past. That’s where we get potentially-lethal strategy-errors such as “our strategy is last year plus 10%” – so ‘inside-out’ that it has no means to test or verify its assumptions against the real world.

So, to summarise:

- value is what the shared-enterprise says it is – which is not necessarily what the organisation thinks it is, or would want it to be

Hence, in turn, the need for value-governance that:

- keeps each service, and the organisation as a whole, on-track to enterprise-values, whilst fully supporting the organisation’s own needs and values

- keeps track of alignment between value-proposition, value-creation and value-delivery, and the related ‘before’, ‘during’ and ‘after’ interactions and flows of the service-cycle

- keeps track of balance between value-outlay (internal and external) and value-return

- keeps track of conversion of invested-value to usable-value in value-stream

- keeps track of conversion of returned-value to beneficiary-value (‘dividend’)

- keeps track of balance between investors/invested-value and beneficiaries/dividend-value

- manages, balances, and keeps track of information-flows and other flows to and from its own ‘child-services’

And all of this applies at every scope and scale, from the code-level interactions of an individual web-service, all the way up to an economics that spans the entire planet.

I hope that makes sense? – if not, over to you to ask for further detail in the comments.

Leave a Reply