Services and Enterprise Canvas review – 3A: Direction

What is a service-oriented architecture – particularly at a whole-of-enterprise scope? How do we describe the relationships between a service and those that direct and manage its actions? What are those other ‘direction-services’? And what happens within those service-interactions?

This is part of the third in a six-part series on reviewing services and the Enterprise Canvas model-type:

- Core: what a service-oriented architecture is and does

- Supplier and customer: modelling inbound and outbound service-relationships

- Guidance-services: keeping the service on-track to need and purpose

- 3A: Direction

- 3B: Coordination

- 3C: Validation

- 3D: Investors and beneficiaries

- Layers: how we partition service-descriptions

- Service-content: looking inside the service ‘black-box’

- Exchanges: what passes between services, and why

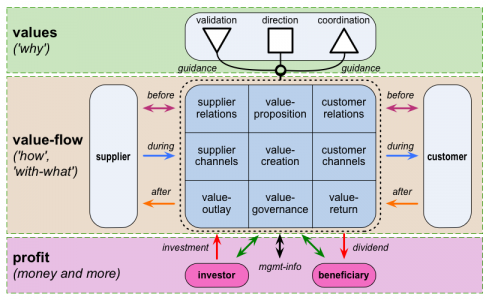

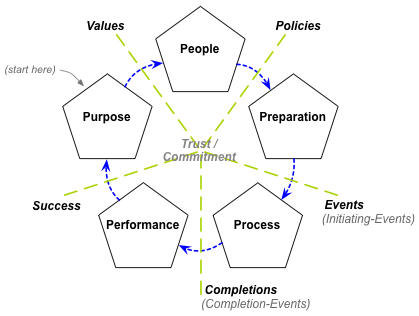

In the previous post in this series, we saw how each service needs support from a variety of other services, to guide and validate its actions, and to coordinate its actions with other services, and its changes over time. (There are also relations with investors and beneficiaries, which we won’t cover here just yet.) We can summarise these relationships visually in the ‘robot-chicken’ layout of the standard Enterprise Canvas model:

And we saw from that previous post that that cluster of services in the ‘guidance services’ block – the downward-triangle, the square and the upward-triangle – as shown above the main ‘horizontal’ value-flow, is based on Stafford Beer’s recursive, fractal Viable System Model (VSM), which we could visually simplify somewhat as follows:

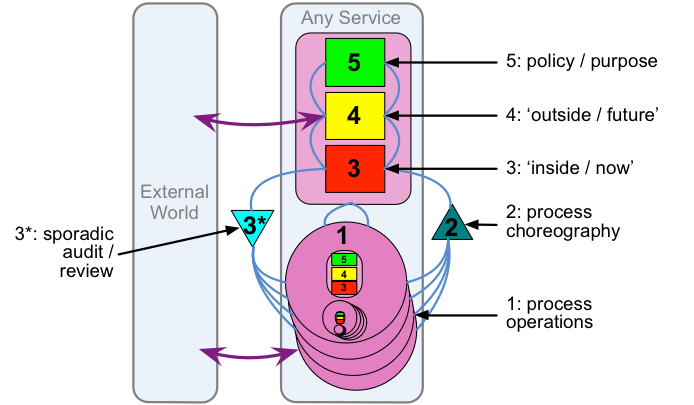

For our purposes, we can simplify this down again into four clusters of ‘systems’ and their service-relationships:

- direction and ‘management’ in general – systems-3 / 4 / 5 (square-symbol)

- coordination and change – system-2 (upward-triangle)

- validation and qualitative concerns – system-3* and extensions (downward-triangle)

- service-delivery – system-1 (circle)

The ‘system-1’ or ‘delivery-service’ is what we would more typically think of as ‘the service’ – the part that deals with the main ‘horizontal’ value-flow, the direct interactions with the service’s suppliers and customers. Although there’s always some correlation between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’, the other clusters of support-services tend not to be embedded within ‘the service’ itself, but are more linked-in via paths of interaction that are not part of the main value-flow. We could summarise these pathways as follows:

Which, for this post, leads us to the direction-services – or, more colloquially, the management-services – to provide direction and change-guidance and resource-management and the like for whatever service it is that we’re current assessing.

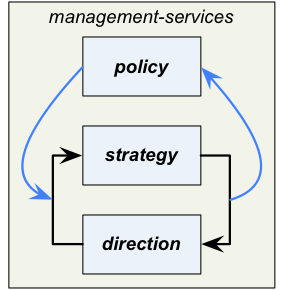

On the Enterprise Canvas diagram, we show it as a single square, but in practice it’s made up of three quite distinct functions or service-types:

- purpose, identity and policy (VSM system-5) – ‘holding the vision’, ‘develop the business’

- strategy, change and business-intelligence (VSM system-4) – ‘watching the outside world’, ‘change the business’

- direction and resource-management (VSM system-3) – ‘keeping operations on-track’, ‘run the business’

We can summarise the relations between these services visually as follows:

Classically, the first two (policy and strategy) would be thought of as staff-management functions, with the third (direction) more middle-management: but remember that this is recursive, fractal – which means that whilst these support-services might be most visible in those business-locations, in practice they reside everywhere, within and/or linked with every service in the respective enterprise.

There’s also a strong cross-link we could draw here with another model, Five Elements:

And the leadership-model that arises from Five Elements:

In this sense, we can view ‘policy‘ as the service that identifies the overall story of the broader shared-enterprise, and the purpose of this cluster of services in relation that story – in other words ‘identity and purpose’, as per VSM – and then engages people into the purpose and promise of that story. In short, it’s very much about ‘feel‘. It’s also somewhat inward-looking, or outward-looking only in the most abstract sense: it’s holding on to something that does not change, in the midst of the changes of the everyday world.

We can view ‘strategy‘ in part as a bridge from ‘feel’ to ‘think’, but as a service its role is more to look outward at the changes in the wider world, and connect that which doesn’t change – ‘policy’ in that broader sense – to that which definitely does need to change in response to the wider world, whether it likes it or not – ‘direction’, and thence the respective delivery-services themselves.

And we can view ‘direction‘ as focussed very much on ‘think’, on preparation for the near-future, and assessing outcomes from the near-past, to help keep the delivery-services – the ‘do’ part of work – on-track to immediate-purpose, within the constraints of available resources and the like.

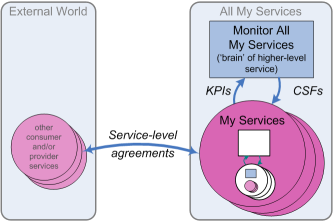

As we’ll see again in a moment, all of these services ultimately need to connect in with every delivery-service, at every level. But the part we’d most often see, in a business-context, is the ‘direction’-role of a manager at the next level ‘up’ from a given service, managing the resources and performance of a cluster of related delivery-services, and typically tracking what’s going on via information about Critical Success Factors (CSFs) going ‘down’, and information about Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and the like coming back ‘up’. This information would be integrated and used for decision-making within the respective ‘direction’-service – indicated collectively by the ‘mgmt-info’ flow on the standard Enterprise Canvas diagram earlier above, coming downward from the Value-Governance cell. Remember, again, that this is recursive and fractal – such as we’d see in a classic reporting-hierarchy in business:

Each of these services may be ‘external’ in some sense to the respective delivery-service in focus for our assessment, but they still need to connect through everything in the respective enterprise. Despite some managers’ notions of centrality and self-importance, in reality we need to be clear that policy, strategy and even direction are actually the responsibility of everyone – even if only in terms of engagement in and personal-accountability for the enaction of those themes. In a service-oriented enterprise-architecture, then, we need to be able to trace the two-way flows around those themes, right the way through every service in the enterprise.

For the direction-services, or management-services in general, we can do some aspects by noting how these ‘external’ services connect into the internal cells or child-services within the Enterprise Canvas model of a service. For example, the ‘policy’- and ‘strategy’-services link strongly with the Value Proposition cell, linking the service’s own product- or service-development to current strategy and overall business-purpose; both ‘strategy’-services and, even more, ‘direction’-services connect to the Value-Creation cell; whilst ‘direction’-services link very strongly into the Value-Governance cell. We could visualise these recursive, fractal threads of interconnection in the style of the VSM, as follows:

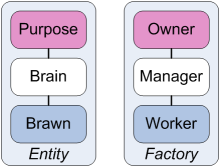

I perhaps need to hammer again on this point about think fractal, not linear. If we think in fractal terms, with all of the roles and functions and flows of these ‘management-services’ fully distributed throughout all of the services, what we end up with is something that is often extraordinarily powerful, extraordinarily responsive, extraordinarily ‘antifragile‘, and fully purposive – where the management-services provide ‘the brain of the firm’, to use Stafford Beer’s original description for the VSM, somewhat as indicated for the ‘Entity’ view on the left-hand side of the diagram below.

But there’s a special-case where the management-services are not fully-distributed, where ‘purpose‘ is retained as an exclusive ‘right’ of a single self-selected group of ‘owners’, and where ‘strategy‘ and ‘direction‘ are withheld as the exclusive ‘right’ of a subset-caste of ‘managers’, with one-way ‘control’ of all services ‘below’ them – as in the right-hand ‘Factory’ side of the diagram below. And that’s when things can go really horribly wrong… even though, at first glance, the two views might appear to be much the same.

There are two key reasons why the ‘Factory’ approach is so problematic. One is this fractal issue, about arbitrarily constraining the fractality of how a service-oriented architecture actually works, and arbitrarily constraining the flows, replacing system-wide distribution of sensemaking and decision-making with a one-way, top-down ‘control’ that ends up being impossibly slow to handle decision-making at real-world speeds. The other reason is that whilst coordination-services and validation-services are actually orthogonal to management-services – and hence necessarily must be somewhat ‘outside’ of management itself – in top-down neo-feudal business structures such as management-centric Taylorism or Fordism, it’s often arbitrarily assumed that all of those services should be subsumed under the ‘control’ of the respective managers:

The result is that everything is forced into silos, with arbitrary vertical boundaries. There’s almost no means to coordinate between them – because that would represent a breach of some manager’s personal authority and remit – hence, in effect, all coordination-decisions have to be pushed further and further up the authority-tree, creating layer upon layer of bottlenecks until we finally reach a pair of managers who are willing to connect across the silos. And not only is there almost no means to keep track of qualitative concerns – the purview of the validation-services, as we’ll see later – but managers themselves (perhaps especially at ‘the top’) are actually deemed to have authority ‘over’ such concerns – in other words, claim to not be subject to those constraints at all. Which can – and too often has – lead to serious problems with senior-managements around (lack of) business-ethics, financial-probity and much, much more.

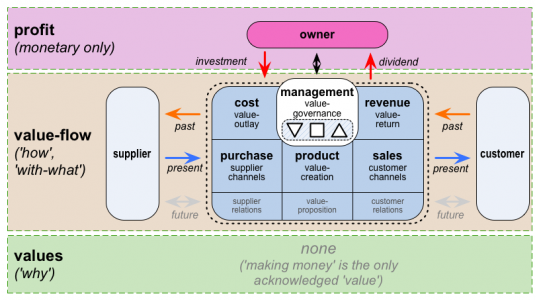

Just to make things even worse, the business-world is still dominated at present by the Friedman Delusion: the notion – which Jack Welch, Steve Denning and other highly-respected business-folks are, increasingly, decrying as “the world’s dumbest idea” – that financial-stockholders are the exclusive ‘owners’ of a corporation, and thus that the respective organisation exists solely for their own financial benefit. When we map out on Enterprise Canvas the results of these two concerns – ‘shareholder-primacy’, and top-down management, with coordination and validation both subsumed into management because there’s nowhere else that they can be allowed to go – then the implications, scale and severity of the resultant mess should start to become clear. It is, in fact an architecture that is guaranteed to fail, certainly in the medium to longer term: and there are all too many real-world examples to illustrate that fact, too.

As a quick summary:

- ‘shareholder-value’ is defined as the sole purpose of the entire system – which means that everything must be measured solely in monetary terms (making qualitative-concerns such as business-ethics all but impossible to monitor or even to describe – and in turn creating huge kurtosis-risks that are all but invisible because they cannot be described in monetary terms alone)

- there’s no means to define any kind of meaningful value-proposition or business-model that is not centred solely around money – most often, ‘value-propositions’ are little more than than random attributes assigned to products and services in the vague hope that they might perhaps, almost by chance or sheer weight of numbers, attract some prospect’s attention

- relationships with customers and suppliers are described solely in terms of how much money can be made from them, or costs avoided to them – inherently poisoning customer-relations and supplier-relations even before they start

- management subsumes all of the guidance-services – direction, coordination and validation – into itself, inherently creating dysfunctional silo-based organisational-structures

- in Enterprise Canvas terms, management places itself in and as the Value Governance cell – inherently past-oriented rather than future-oriented, and unable to see much if anything outside of itself

Visually, the result looks something like this – sort-of like an Enterprise Canvas, but upside-down, back-to-front, no connection to future or broader values, and so past-obsessed that it seriously believes that “last year +10%” is a genuine strategy:

As we’ve seen with the standard layout of Enterprise Canvas, the way that does work is the other way round, or other way up, in which direction, coordination and validation are all properly separated-out from each other and from the more line-management functions of the Value-Governance cell. Those support-services provide their respective means to link the organisation and its services to the shared-vision and values of the broader enterprise, which in turn provides guidance towards the future, and also provides an anchor for value-propositions that actually have real meaning for other stakeholders. (The needs of investors and beneficiaries are also covered appropriately, though we’ll explore that later, in part 3D.) Also, and importantly, there are clear separations between the different types of value-relationships and value-flows:

There’s more detail on other key aspects of this in other posts here, such as ‘Every organisation is ‘for-profit’‘ and ‘Direction and governance flows in Enterprise Canvas‘. There’s also an in-depth analysis and checklists in the post ‘Enterprise Canvas as service-viability checklist‘.

There’s one more very important concern here, though, that is systematically hidden by the rigid top-down hierarchies of the Taylorist model, and is too often missed even in the standard Enterprise Canvas layout: and that’s that management is ‘just another service’. It’s nothing special: it’s just another support-service, in exactly the same way that, say, the janitor is just another support-service – and itself just as essential as management might be to the enterprise as a whole, too. And although, yes, it’s often useful to view management in terms of reporting-hierarchies, there’s actually no reason whatsoever why those should be viewed solely as somehow ‘above’ everything else: in terms of service-relationships, they could just easily be modelled sideways-on, or even ‘below’ the delivery-services.

Yet this is where it gets kinda scary, because it also becomes clear that there is nothing – literally, nothing, in service-modelling terms – that could justify anything more than a moderate difference in pay or privileges between the manager and the janitor: a few tens of percent in pay, perhaps, to cover education-costs and longer work-hours in some cases, but that’s about the limit of it. If we’re to do service-oriented architectures properly, across the whole of the enterprise space – and to gain the huge advantages of that kind of architecture – then we also need to face the fact that we must therefore, and necessarily, also rethink the architectures of management, and work to redesign and rebalance those top-down management-architectures. To say that this could be (mis)interpreted as ‘political’ is probably the understatement-of-the-year, as far as enterprise-architects are concerned: but the inescapable realisation that virtually none of the current mainstream management-models are in any way fit-for-purpose – or for any purpose other than kleptocracy on a mass scale, to be more exact – is a blunt fact that arises as an automatic implication from doing this work. Tricky, to say the least…

Anyway, to summarise:

- every service needs some means to gain clarity on identity and purpose, both of itself within the enterprise, and of the enterprise overall – ‘develop the business’

- every service needs some means to keep track of changes in the ‘outside world’, and to adjust and adapt within itself to those changes, as appropriate – ‘change the business’

- every service needs some means to manage resources, and to balance competition and conflict with other services in its work-milieu for those resources – ‘run the business’

In the cases where the service cannot provide those respective support-services from within itself, it would do so via external links to what we’ve described as ‘management-services’, respectively as ‘purpose’-services (VSM system-5), ‘strategy’-services (VSM system-4), and ‘direction’-services (VSM system-3).

We’ll stop there for now, and move on to explore the ‘coordination’-services in the next post in this series. See you there, perhaps?

And, as usual, any comments or questions so far?

More good stuff.

Good to see VSM mentioned

Thanks, Adrian – and yes, VSM (or at a somewhat-extended version of it) is absolutely central to how Enterprise Canvas works.

Tom,

Great article. You may have explained why large companies so often fail (as partially explained in the innovators dilemma). I also see lots of crossover with the Toyota Lean research and even a bit of MS solutions framework that promoted a team of peers so with the management functions – product, project etc. just another role with different accountabilities. That said some accountabilities are possibly more valuable than others.

Great stuff!

Paddy

Many thanks for this, Paddy – much appreciated.