The point of specialism

What’s the point of specialism? Or, perhaps more to the point, why do we so much argue about ‘the point’? – is it a side-effect of specialism itself?

After the farrago around the last couple of posts here, this is perhaps best described as a bit of a swansong: a last loose end to wrap up, really. And no, I’m not going to argue about it: just place it here in the hope that it might be useful, and leave it at that.

The point I’d like to explore here – as briefly as I can – is that point about ‘the point’, because it goes right to the heart about the fundamental difference in approach between specialist and generalist.

In the hope that it’ll help to clarify what’s going on, I’ll use the SCAN frame as a central reference:

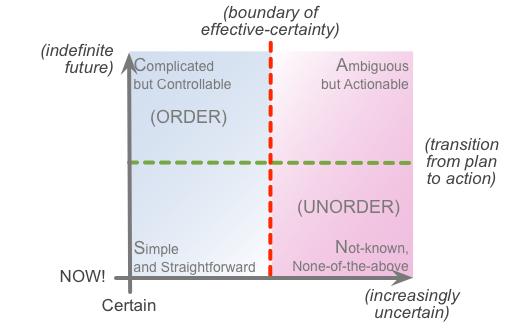

Remember the two dimensions of the SCAN frame: from left to right represents increasing uncertainty; from bottom to top represents increasing amounts of time before action must be taken at the ‘NOW!’.

In a sense, we all become specialists in our own right in every moment, because at the exact point of the ‘NOW!’, every point is special, itself, unique – at the moment-of-action, there is only this, here, now. No-one else has that exact experience: we’re it.

And we alone are responsible for how we choose to act on and interact with what happens there, right in that moment. That’s special.

Yet this is where it gets tricky, because whilst that sense of absolute specialism is true for that one point – that one moment of this, here, now – every other point is both the same as that point, and different from that point, both at the same time. The moment we step back from that one point, and compare one point with another, we’re no longer in that same space. And that’s where that distinction between specialist and generalist starts to come into play.

At first, it’s more a preference than anything else: in SCAN terms, whether we move leftwards towards sameness and certainty, or rightwards towards embracing uncertainty and difference.

Towards the left, we rely more on rules, predefined follow-the-steps work-instructions, tick-the-box checklists – and there is real value in that, because without it we would not be able to do any of the like-with-like comparisons on which so much of science and statistics depend. That’s where specialists tend to be most comfortable.

Towards the right, we rely more on principles, guidelines, personal-experience – and there is real value in that too, because without that we would not be able to work well, or at all, with the natural differences and uncertainties inherent throughout the real world. That’s where generalists tend to be most comfortable – or, at least, comfortable with being uncomfortable, because it’s always a somewhat-uncomfortable place.

The catch is that people who do things – especially people who do things well – are expected to deliver the same results in future, when working with different moments-of-action, different moments of ‘NOW!’. And explain to different people how to get to those same results, too. In other words, different as same: you can see the trap right there, right?

In practice, the people that we’d describe as specialists are those who can be relied upon to ‘deliver the goods’, and show others how to ‘deliver the goods’, as long as things stay – or can be made to seem to stay – to the leftwards of that ‘boundary of effective certainty’. The greater the real skill of that specialist, the further rightwards their ‘boundary of effective certainty’ will be, relative to that of others, though the further right they go, the less they’d be able to explain it – yet that difference does somewhat help to create that aura of ‘specialness’ that sometimes surrounds the great specialists…

The people we’d describe as generalists do also ‘deliver the goods’, though often in ways that make no apparent sense to anyone else. (And too often, too, after what seems like way too much, well, dithering – in part because once it becomes self-evident that everything depends on everything else, it’s kinda difficult to decide on what actually to do.) Perhaps unfairly, though in some ways accurately, it’s sometimes said that generalists get things done only by getting specialists to do it for them – though the generalists’ trick, of course, is in knowing which specialist to call on at each moment…

A specialist does one thing really well. A generalist links things together. Which implies, in practice, that to get all things done well, linked together, the right things done right – things work better when they work together, on purpose – then we’d need also the right mix of specialists and generalists, working together in a unified way.

Which, unfortunately, is what too often does not happen in practice.

Instead, what we too often get is a fundamental error: in SCAN terms, getting confused about the relationship between plan and action. Specialism delivers the goods at the NOW! – no-one doubts that. Yet its productivity takes place only at that point of NOW! – not necessarily anywhere else. If we confuse the disciplines of the NOW! with the very different disciplines of thinking and planning and cross-reference and experimentation that happen before the NOW!, we’re likely to get into a mess. And that’s exactly what happens whenever generalism is under-valued and specialism on its own is over-valued: for example, in Taylorist theory, specialism is elevated to the level of a cult – often in the worst possible sense of that word…

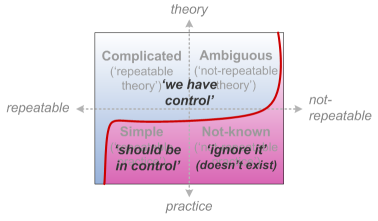

Which is what leads too often to the kind of specialism-trolling mess that we could illustrate in SCAN terms as follows:

A single specialist finds something that works well for a specific need in a specific context. But as they move back from the moment-of-action, move back or ‘up’ towards reflection, review and planning, they generalise those outcomes in the wrong way – reasoning from the particular to the general, rather than from the general to the specific. Because their specialism works in one place, they assume that it will and must work the same way everywhere – ignoring the contextuality that made it work well in the first place. The all-too-human drive for pseudo-certainty usually plays a significant part in this, too…

It’s where we get the cult of the expert, who knows all of the theory but none of the real-world practice. It’s where we get the disaster of ‘best-practices’ that aren’t. It’s where we find the IT-obsessives, still pushing the same old line that IT alone can deliver ‘control’ where, in reality, no control is to be had – not in any absolute sense, at least. And it’s where we find specialism-trolling, from which we get arbitrary constraints placed on possibility, and the disastrous impacts of senseless, stupidly-shallow term-hijacks – just to keep too-narrow specialists happy in the delusion that what works, for them, in one specific place, must work the same way for everywhere else. A sad variant, in fact, of that old slogan of self-centrism, “the personal is political” – and hence Not A Good Idea.

As we hit up against complexity and real-world chaos, we need generalists to ‘join the dots’, to link across the whole-as-whole. Yet the specialists’ reflex response to complexity so often seems to be a reversion to ‘more of the same’, a move from specialisation to hyperspecialisation – yet more fragmentation from ‘dotting the joins’ into ever smaller and smaller-grained dots. It’s a tactic that, in too many cases, serves only to turn complex ‘wild-problems’ into irresolvable ‘wicked-problems’: in short, yet another Not A Good Idea…

Specialisation does have real value, of course: every specialisation arises from a point-solution that works. Which is why every specialist does have their own valid point to make. Yet people get so hung up on each point that they tend to miss the real point: that in any real architecture, the only point is that there is no ‘the point’ – everything depends on everything else, there’s only ever ‘the everything’, in which everywhere and nowhere is ‘the point’, all at the same time.

That point is perhaps where we’d be best to leave this, and move on.

Leave a Reply