RBPEA: Constraints and corollaries

Enterprise-architectures should, in principle, apply to any enterprise, at any scale. But what happens when we scale our enterprise-architectures up to the ‘really-big-picture’ (RBPEA) level, with a literally global scope? What non-negotiable constraints would we hit up against? What corollaries would follow from those constraints? And how would those implications echo back down to the more everyday levels at which our enterprise-architectures more usually work?

The initial inspiration for this post – or what will probably be a series of posts on these aspects of RBPEA – comes from one of Gerald M Weinberg’s tales in his classic ‘The Secrets Of Consulting‘, about making strawberry shortcake.

Imagine, he says, that you want to make strawberry-shortcake, and what you have in front of you is a recipe sufficient for four people. If you want to make it for just two people, simple: you just halve the ingredients. For eight people, you’d double it. For a small cafe, you might have varying needs – two people one day, eight the next – so you tweak the recipe each day. In other words, no problems, as long as the numbers and the timescales remain much the same.

But imagine instead that you’re a caterer for a huge conference, and the conference-organiser says that they’ll need strawberry-shortcake of the highest quality for 10,000 people at exactly 8:45am, all with fresh cream and with every piece of shortcake still warm from the oven. The basic recipe remains the same – but suddenly a whole swathe of previously-invisible factors and assumptions will make their insistent appearance. As Weinberg says, you now starting getting into strawberry futures, the design and operation of high-throughput mixers and ovens, and negotiating with the Teamster’s union to ensure the delivery of truckloads of flour and fresh cream…

(The usual way to ‘solve’ these problems of scale is to drop the quality – and yeah, almost all of us will have experienced the un-joys of that: cardboard cake, anyone? With pseudo-cream and vaguely-flavoured-sugar jelly? Yuk… Not A Good Idea…)

Yet in reality those ‘hidden’ assumptions and constraints do still apply at the smaller scales: the only difference is that someone other than ourselves would usually have to deal with them… And the catch is that because those constraints still exist in the overall context, but we’ve seemingly been able to ignore them in our smaller-scale system-design (“just follow the recipe, ignore everything else”), there still remain situations in which they can suddenly come back to bite us and cause our system to fail, seemingly ‘without warning’.

So let’s have a look at some of these real-world constraints – because, from the perspective of ‘the architecture of the enterprise’ at a truly global scale, the implications of some of them are truly worrying. To me, as you’ll see, what those constraints are telling us is that the way we’re doing things right now is not only horrendously inefficient and ineffective, it’s inherently non-viable, and already almost non-survivable – in fact already dangerously close to a global suicide-pact. Not A Good Idea…

And we don’t have much time to turn things around – especially at the literally global scale that these changes will need.

Better get started, then.

But where to start? One place would be with the bald assertion that “You can’t argue with physics” – there are some things that we can’t bypass or change, and if we pretend otherwise, we are going to get into serious trouble.

Hence, for example, the blunt reality that you can’t have infinite growth on a finite planet. And yet almost every economist and politician is still trying to avoid this fact, promoting economics-models and policies that not only assume infinite growth, but cannot work unless there is infinite growth. Oops…

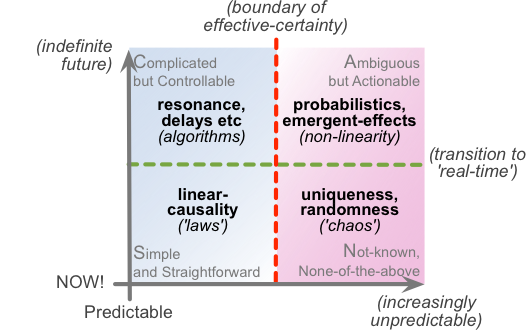

Yet we also have to be careful about the meaning of “You can’t argue with physics”. A lot of people seem to mistake that to mean that there are fixed rules for everything, but reality is that it’s a bit more complicated (or complex, or something?) than that, as we can show with a SCAN crossmap:

Much of physics is rule-based, yes – simple, linear, causal ‘laws’. But there are also hard-systems complications such as feedback-loops and delays; there are ambiguities introduced by network-effects, emergent-effects, the inherent-uncertainties of probabilistics and other non-linearities; and there are the ‘unknowables’ in chaotic-systems, radioactive-decay and other inherent-uniquenesses – all of which are part of physics too. All of which leads us to an inescapable paradox:

- the only absolute rule is that there are no absolute rules

and its corollary:

- the only absolute truth is that there are no absolute truths

(The latter fact can be kinda tricky, of course, in certain social contexts that do assert, absolutely, that they alone have the only absolute truths – with no allowance for either paradox or parody…)

Or, to turn it the other way round, into a more Fortean sense:

- there’ll always be some fact that doesn’t fit our theory

The implications of that are huge, as Paul Feyerabend explains:

New theories came to be accepted not because of their accord with scientific method, but because their supporters made use of any trick – rational, rhetorical or ribald – in order to advance their cause. Without a fixed ideology, or the introduction of religious tendencies, the only approach which does not inhibit progress (using whichever definition one sees fit) is “anything goes”.

And whilst some might dismiss that as an exercise in epistemological anarchism, there are plenty of real-world examples too. One of the classic corollaries is an aspect of Claude Shannon‘s information-theory, in which he demonstrated that there is no practical way to eliminate all noise in signal-transmission, because to do so would require a perfect conductor of infinite size.

We therefore need our architectures to design for such inherent-uncertainties – rather than pretend that they don’t exist. And we need to do so with the honesty and rigour that Feyerabend’s model demands of us – rather than relying, as is still all too often the case, on “the use of any trick – rational, rhetorical or ribald – in order to advance [our] cause”. Or, for that matter, on the self-delusion, selective-myopia and ‘policy-based evidence‘ that are probably much more common than deliberate deceit…

What that SCAN crossmap above makes clear is that the contexts we deal with at every scale of enterprise-architecture do not solely follow simplistic rules or ‘laws’, yet neither is it as chaotic as Feyerabend’s “anything goes”: and there are also many complications to the ‘laws’, and many ambiguities and emergent-effects from the apparent ‘chaos’.

(All of which can perhaps sort-of be described as ‘complexity’, with simple rules and suchlike behind emergent effects, as per A Certain Welsh Framework – but I’d admit that I’d see most of that as merely yet another example of Feyerabend’s “use of any trick” to elide over the real complexities and chaos beneath the supposed ‘complexity’…)

In short, I’d suggest that the only way to make sense of any system is to accept it as a system, a whole-as-whole – in all of its simplicity, all its complications, its ambiguities, its uniqueness and chaos, all at the same time.

Which brings us to the human aspect of ‘enterprise’, all the way up to the ‘really-big-picture’ scale.

Human enterprises are systems – or, more accurately, systems-of-systems. And, just as with any other system, one of the simplest ways to describe what goes on in those enterprises is as meshworks of services, all interrelating with and interdependent on each other in what we might summarise as relations of interlocking mutual responsibilities.

By ‘responsibility’ here I mean in it in its literal form, as ‘response-ability’ – the ability to respond to the stimulus and implicit service-request in the interrelationship. The same applies in physical-systems, in biological-ecosystems, and so on, all the way up to a planetary scale, and (for physical-systems at least) further and far further beyond. The mutuality and interlocks of those interrelations are what enable the system to operate as a system.

The only difference, in the human context, is the addition of some element of choice in those interrelationships, and in the responses to other players and elements within those system-scale interrelations.

In other words, the ground-base for all human systems is interresponsibility – mutual, interlocking responsibilities to and with each other within the overall system.

For which, in turn, real-world observation of human systems indicates that:

- each person has different skills and ‘response-abilities’

- the human-system requires all of those skills and ‘response-abilities’ (or at least some of those skills and ‘response-abilities’ at any given moment or for any given interaction) in order to function as a system

(Or, to put it another way, every in a human-system is part of and needed in that human-system.)

We also note that in any viable architecture:

- every element, and no single element, is ‘the centre’ of the system, all at the same time

Which, in turn, indicates that in any human-oriented (enterprise) architecture:

- every person, and no one person, is ‘the centre’ of the system, all at the same time

Which, unfortunately, is not how a two-year-old sees the world…

During that specific phase in child-development, the child has developed their awareness of the world such that they can understand the concept of Other, and can grasp the existence of a world beyond ‘I’. What they don’t yet grasp at this stage is the concept of Other as peer, or equal: that shift in perspective typically won’t start to happen at all until towards the end of that stage of ‘the terrible twos’. The result is that during this development-phase, the child is likely to hold an absolute, unshakeable belief that they – and they alone – are ‘the Centre Of The World’, and that the Others exist solely to serve their needs.

In effect, the child at that stage views everything as their personal, exclusive possession, and that Others alone are responsible for the consequences of that assertion of possession. The inverse is also true, as ‘anti-possession’: a child’s method for dealing with no-longer-wanted items such as an ice-cream-wrapper is to dump it on someone else…

(Looking around in everyday society, some of this will no doubt seem painfully familiar: certainly all too obvious that many people have never fully grown out of this literally childish stage. Hence what I term a paediarchy – ‘rule by, for and on behalf of the childish’…)

In more adult language, we would say that the child would claim to possess ‘the right to be not-responsible’ – that the child alone claims to have ‘rights’ of absence of responsibility, whilst asserting that others alone have the responsibilities to make the human-system work as a system.

In turn, the assertion of ‘non-responsibility‘ breaks the mutuality and interlocks upon which the viability of the system actually depends. So if we allow that notion of possession to exist, we have to build all manner of compensatory kludges to try to bring interactions back into balance again.

That’s not so hard to do, of course, when it’s just one two-year-old’s possessive-temper tantrums that we’re dealing with. But if the child doesn’t ‘grow up’, and continues to hold on to this notion of possession of this exclusive ‘right’ to be ‘the Centre Of The World’, then we hit up against a whole swathe of much more serious problems.

One of these problems, for example, is that we can easily end up with a context in which people are actively rewarded for being childish, and actively penalised for behaving with more-adult responsibility. Not A Good Idea… But unfortunately it’s one of the direct outcomes of a rampant paediarchy – a paediarchy that inherently arises whenever childish notions of possession are allowed to hold sway all the way into adulthood.

Another key problem is that, as above, possession breaks the mutuality of interresponsibilities upon which the real human-system actually relies. Once we allow myths of possession to take root as the basis for an economics, we end up being forced to build layer upon layer of compensatory-mechanisms to try to rebalance the resultant distortions of the system’s natural flows.

For example, once we base the economics on a concept of possession:

- we now need to exchange possession of resources and services, rather than them naturally flowing in response to need

- we need a concept of property and property-rights in order to establish who has possession, in order to identify ‘rights of exchange’

- we need a concept of barter, and relative-valuation of each of item of exchange, in order to establish ‘fair exchange’

- we need a concept of abstract currency in order to compensate for the point-to-point limitations of barter, and to re-enable a broader flow

- we need a concept of debt and debt-based finance in order to compensate for the time-limitations of point-to-point exchange

- we need a concept of finance and, thence, financial-derivatives in order to balance out the individual-oriented basis of debt-based finance

Each of these layers is building on, and trying to compensate for, the unintended-consequences of the previous layer – all of which ultimately go back to that one arbitrary and, in systems-terms, inherently-invalid assertion of ‘possession’. Everything we see as ‘everyday economics’ and the like is built upward from that one distortion that blocks the natural flows of mutual interlocking interresponsibilities. Or, in visual form:

To put it bluntly, our current global cultures and their concomitant economics are utterly possessed by possession. The result is what, to most of us in ‘the trade’, too often looks like an almost irredeemable mess…

It’s also the reason why so many of those attempts at fixing the problems at a global or even local scale not only don’t work, but won’t work, in fact cannot work. All of them try to fix some aspect much closer to the surface: the banking-system, for example, or the currency-model, or calls to “go back to barter”, or the age-old clash between communists and capitalists as to who should or should not have the rights to property, the rights of possession. Yet the blunt reality is that all of that futzing-around in any or all of those areas will never make any really significant difference to any of the mess: they’re all just variations on a theme of shifting the deckchairs on the Titanic.

The real problem – the real iceberg that’s sticking out sharp-edged deep beneath the surface – is this literally-childish assertion of ‘possession’: and unless we stop pretending that it doesn’t exist, and doesn’t work, we’ll be going nowhere but down – taking almost everything else with us, if we’re not darn careful…

To put this in visual form:

Yet there is a way out of this – a way to redeem the mess, a way to perhaps stop the Titanic before it hits the iceberg. The reason that possession doesn’t work, and can’t work, is because the assertion of ‘rights of possession’ is itself an arbitrary assertion of a rule. A literally self-centred rule imposed upon others, but a rule nonetheless. And as we saw way back at the beginning of this post, the only absolute rule is that there are no absolute rules.

Hence, for example, the claim that possession is some kind of ‘an absolute God-given right’, a ‘God-given rule’? Well, yes, that might well seem satisfying to some. But the blunt reality is that it’s flatly contradicted as such by the real laws of physics – and to attempt to fight against that is somewhere between an act of futility, and an act of stupidity of a pretty high order. Oops…

And to assert that possession is ‘human nature’? Well, yes, it is – for a two-year-old, who’s necessarily shielded for the most part from the economic consequences of their childish behaviour. In terms of what should be normal child-development, that behaviour is not ‘human nature’ past perhaps three years old: and that it so much does remain part of ‘human nature’ in our cultures is more a reflection on the deep dysfunctionality of our cultures than on ‘human nature’ itself.

And to those who might point to Darwin and Huxley, and their echoes of Hobbes’ notions of “nature red in tooth and claw”, of possession-run-rampant? To counter those myths, we might equally point to Kropotkin, and ‘mutual aid‘ in animal-ecosystems – because that too is equally ‘human nature’ – and animal-nature too.

For the most part – and certainly for human adults – possession is a choice: nothing more than that.

It’s also not a good choice, or wise choice, in the sense that it’s now increasingly clear that it’s not a survivable choice – especially in the longer term.

Kinda important to start seriously questioning that choice, then – especially as that iceberg is getting closer and closer on the current course of global Titanic with every passing day…

No matter how much we might want it to be otherwise, you can’t argue with physics, or any of its corollaries, such as summarised in that SCAN diagram earlier above. Might be wise to take more heed of that fact, in our enterprise-architectures and beyond?

Regarding:

“the only absolute rule is that there are no absolute rules”

I have a similar favorite aphorism that I think applies:

“All generalizations are false, including this one”.

The point is that some generalizations are in fact true enough to be useful, but many are wrong enough that they have to be applied very carefully.

So while I agree with your assertion, given the “absolute” qualifier, I think it may lead us to “throw the baby out with the bath water”.

Nothing is perfect, but we can often get away with pretending some things are. The trick is knowing which ones. Once upon a time you noted that I had been given a rubber stamp that said “It depends …”, and I noted that it came with another one that said “Yes but …”.

It’s like Newtonian mechanics. In an absolute sense, it’s an egregious simplification of reality (i.e., relativistic mechanics, or at least we currently think so) but for almost all practical purposes it works just fine. The trick is knowing when it doesn’t work just fine, and what to do in such a situation.

I cite again one of my favorite papers, Parnas and Clements, “A Rational Design Process: How and Why to Fake It”.

len.

Thanks, Len – and you’re right on all of that, of course.

Re “The trick is knowing when it doesn’t work just fine, and what to do in such a situation” — the first requirement is to stop pretending that the ‘law’ always applies everywhere, and thence to recognise that there are indeed cases when “it doesn’t work just fine”. Only then is it possible to develop some kind of means of detecting or intuiting when it might not “work just fine”, and thence be able to switch between alternatives according the reading of that context. That’s the ‘It depends…’ part, of course: but we first have to acknowledge the existence of the variance – which we can’t do, for example, if we’re over-reliant on ‘policy-based evidence‘. It’s kinda tricky (huge understatement…)

One of the concepts I find useful is Jack Cohen and Ian Stewart’s notion of ‘Lies-to-children‘:

Again, the first requirement (as you also say) is to acknowledge the paradox. The moment we forget that the ‘lie-to-children’ is only a ‘lie’, we’d be in deep trouble. Phrases such as “For the purpose of simplification … [simplified-explanation] … but remember that it may not necessarily follow this pattern” are crucially important, but too often glossed-over or omitted entirely. Not A Good Idea…

(The only critique I’d make of what you’d said above is about that rubber-stamp of “Yes, but…”. In impro-theatre and the like, the term used is not ‘Yes, but…’, but ‘Yes, and…’. In practice, the distinction turns out to be crucial, as ‘Yes, and’ takes all of the previous flow, and builds upon it with something new, whereas ‘Yes, but’ negates all of the previous flow, and brings everything to a grinding halt. Shifting from the reflex ‘Yes, but’ to the include-and-extend ‘Yes, and’ is acknowledged as one of the hardest habits for impro-performers to learn, but it’s the only one that works. We need to do much the same in our enterprise-architectures too.)

A nit of sorts — my understanding of the use of “but” as a conjunction is not that it implies negation, but rather that it adds a contrasting observation. Examples from one of the online dictionaries:

“You can take Route 14 to get there, but it may take you a little longer.”

I.e., the “but” does not imply that you cannot take Route 14 to get there.

“We enjoyed our vacation a lot, but it was expensive.”

I.e., the “but” does not imply that we did not enjoy our vacation.

Surely the “Yes” in “Yes, but …” is a strong indicator that negation of the antecedent is not to be construed.

len.

Understood. The usual recommendation, because of that implicit negation of ‘but’, is to use ‘yet’ as an alternative – for example:

“You can take Route 14 to get there, yet it may take you a little longer.”

“We enjoyed our vacation a lot, yet it was expensive.”

It can be somewhat tricky to remember to use ‘yet’ in place of ‘but’ – and yeah, I know I forget to do so rather too often myself – yet it’s essentially the same shift as in impro’s insistence on ‘Yes, and…’ (include and extend) rather than ‘Yes, but…’ (which tends to bring the flow of improvisation to a grinding halt).

Yes, and we seem to need this kind of discussion at this time more than ever, as the universe of enterprise seems to be more and more myxogastrial with each passing day.