Architecture as boxes, lines and glue

What do architects do? And why?

At this point we’d usually reach out for some apposite metaphor…

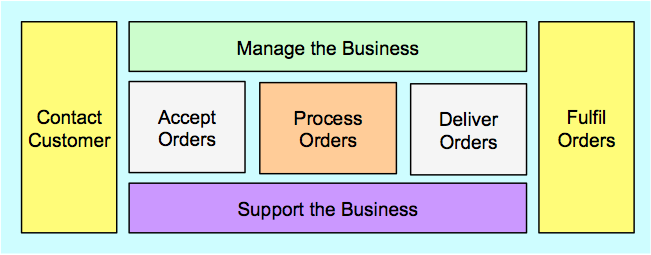

And yes, by far the most common metaphor is ‘boxes and lines’, or ‘boxes and arrows’. If we take the most stereotyped, ‘boxy’ view of the organisation:

…then what architects would typically do is to populate the details of those boxes, and describe the relationships and links between those boxes. Which leads, inevitably, to toolsets and diagrams that look like this:

…yet about which Phil Beauvoir – creator of the Archi toolset shown above – once commented:

my three-word review of all existing tools (including Archi) is “DULL DULL DULL”

Or, as he put it in a recent blog-post, ‘senseless figures in front of a mirror‘.

“Senseless figures”? “Dull dull dull”? As a summary of much of the architects’ everyday work, yes, ‘boxes and lines’ is valid enough as a metaphor, as far as it goes – but perhaps not the most inspiring one we could choose?

In which case, what else might capture better the spirit of the work?

For one option that might work, I’d go back further into my own past. I started out my career as a graphic designer, focussed mainly typography and typesetting. I then got sidetracked somewhat into software-development as a means to get better value from the insanely-expensive typesetting-machines we used, by connecting them to the then-new microcomputers – we were probably amongst the first in the world to do anything that resembled what would now be seen as desktop-publishing.

One of the most eye-opening influences for me in that work was Donald Knuth‘s masterful description of his TeX typesetting-system – fascinating, if to me still largely-impenetrable, both then and now. I love it, though I’ll admit I’ve never been able to make sense of it… – it’s way too complex for my much simpler needs. Yet underlying TeX is something that’s outright amazing in its power and simplicity – its core metaphor of ‘boxes and glue‘:

All of that crazy macro stuff [the TeX markup-language] generally ends up by producing two kinds of things: Boxes, which are things can be drawn on a page, and glue, which is invisible stretchy stuff that sticks boxes together. This is the part of TeX that is amazingly, gloriously, magnificently brilliant. It’s an extremely simple model which is capable of doing extremely complex things.

What happens, then, if we apply that ‘boxes and glue’ metaphor to architecture in general? Typesetting-layout may seem simple relative to the architecture of an entire enterprise, but it’s still an architectural problem in its own right – which suggests there may be clues there that we could re-use elsewhere. So let’s start again with that stereotyped ‘boxy’ view of the organisation:

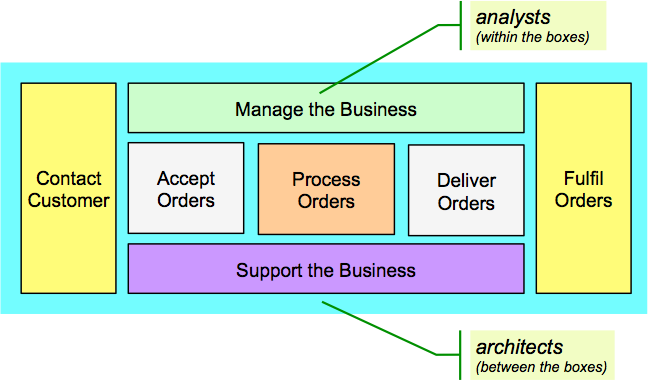

The ‘boxes’ that represent the various core functions of the organisation are all visible enough; yet the ‘glue’ that connects them – the pale-blue in the graphic above – is much less self-evident, and we often have to make a deliberate effort to take notice of it. (That’s a key point explored in another recent post here.) The ‘glue’ – the “invisible stretchy stuff” – is what holds together all of the ‘boxes’ that make up the activities of the organisation.

The Taylorist dream for the organisation is an arrangement of boxes so stable and so perfectly interlocked that it needs no glue at all. That’s the ultimate aim for that style of business-analysis, anyway. Yet it’s an aim that’s simply not achievable in the present-day world: all of the boxes are changing in shape and size, all of the time, in response to real-world pressures, and all the nesting of boxes-within-boxes-within-boxes is changing all the time, too. Which means that, inevitably, there’s a need for ‘invisible stretchy stuff’ to hold it all together.

Which means there’s a need for people who can work with this ‘invisible stretchy stuff’ that holds everything together.

Otherwise known as architects – the people who work between the boxes:

Who are also the people who work with the ‘lines and arrows’ that connect between the boxes.

Which suggests a richer metaphor for architecture: Boxes, lines and glue.

That’s the metaphor that we need.

Which, to bring us back towards where we started, brings us to a comment by ‘jre’ on that post about TeX as ‘boxes and glue’:

Your disquisition on boxes and glue hit me like a hammer: I never realized it until you explained it so well, but the ideal of typesetting beauty in TeX is a minimum of ugliness, and what TeX does is solve a variational problem.

Heavy, man.

Architects often struggle to explain what it is that they do, and the business-value of what they do – the value-proposition for enterprise-architecture and the like. Part of the problem, of course, is that architects mostly work with that ‘invisible stretchy stuff’, in the ‘invisible’ space between the boxes – which makes it doubly-invisible unless we put in the effort to make it visible again. But perhaps the hardest part of the problem is that what architects do is, by its very nature, it’s just so darn hard to describe: head-bangingly complex, is one way to put it…

Yet if we paraphrase that comment above, then we could summarise it like this: architects continually (re)solve a multi-dimensional, multi-layered, fractal, dynamic variational problem, whilst always striving for the minimum of ugliness, in every possible sense.

Heavy, man.

But practical, too.

Architecture as boxes, lines and glue: a useful metaphor, perhaps?

Ahh, this is nice and fun. Boxes, glue and don’t forget: *penalty*.

We share a love for design (many architects do) and in this case for typesetting (I managed the main Mac OS TeX distribution between 2000 and 2006 and lost a lot of time — TeX can do that to you). My avatar comes from that period.

PS. Chess and the Art of Enterprise Architecture was typeset with TeX (character protrusion and all) using the ConTeXt package.

We need multiple metaphors to make sense of organisation, as per Gareth Morgan’s book ‘Images of Organisation’. Boxes and lines are not a good way of describing people’s behaviour for example and the addition of the glue concept doesn’t really help me that much.

But your metaphor does make sense to some extent. There’s a similar viewpoint in this item about maintainers versus innovators, and if you read the comments, you’ll see one contributor use a ‘bricks and mortar’ metaphor, and proudly describe himself as a ‘mortar’ person.

Interestingly this is where the oft-used ‘Lego-Bricks’ metaphor breaks down.

Whoops forgot to add the link to the previous comment. Here it is:

http://www.citylab.com/design/2016/04/how-maintainers-not-innovators-make-the-world-turn/477468/

I prefer the lid of a jigsaw puzzle analogy, we provide a picture of the desired state, bound by straight edged pieces, and identified by a certain number of components which depicts complexity.

As long as architects keep thinking from practice as a starting point, they won’t contribute to a sustainable future. The technique can work; it’s often the vision that fails.

Architects are ugliness minimisers: love it!