On sensemaking in enterprise-architectures [3]

How do we make sense of uniqueness? How can we use uniqueness? And how do we make appropriate decisions when some or all of a context is inherently unique?

In the first post in this series, we skimmed through Max Boisot’s I-Space and its impact on sensemaking in relation to complex-adaptive-systems. I then added a bit about my personal background, and why my own work focusses much more strongly on the individual context, the individual and personal moment of action, and its expression as personal knowledge and personal skill. Finally, we saw a quick overview of why uniqueness or ‘particularity’ is important in enterprise-architectures.

In the second post in the series, we had a brief exploration of why Boisot’s I-Space and similar frameworks don’t fit well with the sensemaking-needs for unique contexts – and illustrated this point with the real-life example of Flight 1549, the so-called ‘Miracle on the Hudson’.

In this post, I want to explore the different types of sensemaking that need to happen at ‘business-speed’ – especially when we have to cope with uniqueness as well at that speed.

In the final post in this series, which will follow this one, I’ll summarise some of the issues around how to balance the sensemaking techniques at ‘business-speed’, and the architectures that we need to support such forms of sensemaking.

First, though, a couple of Tweets to illustrate why this matters:

- SAlhir: RT @DennyCoates “Ideas can be life-changing. Sometimes all you need is just one more good idea.” – Jim Rohn

- CreatvEmergence: The difference between the unknown which leads to confusion and the unknown which leads to emergence is intention with creativity

So: ideas, intention, creativity, ‘life-changing’, even – all at ‘business-speed’. Let’s get down to it?

Making sense, making decisions: ‘considered’ vs ‘business-speed’

In an earlier post I contrasted a ‘considered’ approach to sensemaking, versus ‘business-speed’.

A ‘considered’ approach assumes that there is available time in which to make sense of the context. Formal ‘hard-systems thinking’, for example, tends to focus on analysis, whereas a ‘soft-systems‘ or ‘complex-systems‘ framework such as Cynefin tends to focus on experimentation and emergence. All of these methods rely on an iterative cycle of information-gathering and review – ‘sense / analyse / respond’ or ‘probe / sense / respond’, in Cynefin terms – that takes a significant amount of time to execute each iteration. There are ways to speed up the analysis/experimentation cycle, but in practice there is probably no way to make it work at business-speed, at or close to the real-time ‘now!‘.

A ‘business-speed’ approach assumes that there is little or no time in which to assess, analyse or experiment in the context, yet sensemaking and intentional decision-making must still take place. Whilst the ‘considered’ frameworks do make various recommendations here, in my experience they’re mostly aimed at gathering information to bring back for analysis or experiment – which actually doesn’t help that much when we’re in the real-time context. For the latter, we need something different.

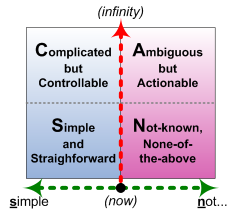

To summarise this in SCAN terms, look first at the core graphic, with its two axes of decision-logic and time-available-before-decision:

In practice, methods for analysis (for the ‘Complicated’) and emergent experimentation (for the ‘Ambiguous’) are only viable if there’s a fair amount of time before a choice must be made and expressed in immediate action. At ‘business-speed’ – at the moment of action – time-to-decide is often compressed right down to the single ‘horizontal’ dimension of real-time decision-logic:

At that level, we need radically-different methods to those we would use in more ‘considered’ sensemaking. In principle, it’s a continuous spectrum of modality of decision-logic, but the crucial distinction is the ‘Inverse-Einstein’ test:

- if we do the same thing and get the same results, we’re ‘in control’ (whatever that means in the context) – which places us on the left-hand ‘Simple’ side of the spectrum

- if we do the same thing and get different results, we’re not ‘in control’ – which places us on the right-hand ‘Not-simple’ side

Again, it is a spectrum, and in real-time contexts we typically move back-and-forth across that spectrum, often at very high speed. For simplicity, though, we’ll split this exploration into those two parts: Simple, and Not-so-simple.

At the Simple end of the scale…

For here, the ‘considered’ tactic is ‘sense / categorise / respond’. Which is valid in its own way, but definitely not sufficient – not least because those categories have to come from somewhere…

[I remember a consultancy-session with a large security-organisation: “We have a rule for everything!”, they said proudly. “What happens when you come across something new for which you don’t have a rule?”, we asked. “We make up another rule, of course!” “Yes, but when do you make up this new rule?” “After the event, I guess…”. “So how do you choose what to do during the event itself?” An interesting silence…]

Machines work on rules. Most IT-systems work on rules. Work-instructions are rules, of a kind. As mentioned in the previous post, checklists provide very important rule-like support for real-time action. Yet rules themselves are not the whole story, because the capability to apply those rules also has to come from somewhere – which likewise is not always as simple as it seems.

And when the ‘agents’ for that capability are real-people, some other quite different aspects often come into play. This is what we might call ‘body-learning’, literally embodying very-high-speed response that some people might describe as ‘instinctive’, but it’s an ‘instinct’ that’s grounded in often very long periods of first-hand practice. What makes these responses seem instinctive is that they occur in sequences that are far faster than are feasible for rational thought – and yet it is in response to real-time events. Consider, for example, the kind of ‘instinct’ that causes you to press your foot down on an imaginary brake-pedal when a passenger in a car…

[I’m playing in an Irish-music session at the local pub: I’ll freely admit I’m no master-musician, so I’m keeping well in the background here, yet still keeping pace with everyone else. It’s a very fast reel we’re playing, probably upwards of 150 beats per minute: that’s more than 10 distinct notes a second, or an average of perhaps 20-40 finger-moves a second, often not in linear sequence. The tune ends, another starts, still exactly on the beat; just about everyone switches straight away to this new tune, within a note or two at most – though no-one had rehearsed any of this beforehand, or even knew which tune would come up next.

And yet the typical reflex-response interval for rapid change like this is around 200 milliseconds – the time taken up by at least two notes at this speed, maybe more. So this is faster even than reflex-response, let alone conscious decision: clearly something more than just ‘considered’ sensemaking and decision-making is going on here…]

What’s going on in this body-learning is that patterns and sequences are embedded through constant repetition – in theory, itself a Simple process. Quite where these patterns are executed in physiological terms I’ll admit I don’t know, but the speed suggests it’s run via local ganglia – there certainly isn’t time to run solely from the brain. The overall instructions to run each pattern may come from the centre – but not every move.

[There’s a nice analogy here with the distributed parallel-computing system we used for a major long-duration aircraft test at the lab, starting almost two decades ago. There were over a hundred independent local-controllers, each managing their own control-law for their actuators, sensors and feedback-loops. All that the central-controller had to do was pass required overall positions or loads to the local-controllers every half-second or so; the local-controllers handled all the rest, including any unplanned-for interactions across the system. The control-intelligence was distributed in real-time as an emergent property of the whole system – not embedded solely in the central-controller, as it would be in a classic ‘hard-systems’ model, or a Taylorist model of a business.]

Training usually takes place in a ‘safe-fail’ context such as a simulator, where no-one gets hurt if – or more likely when – things don’t work out as intended. With more experience, the pressure gets ramped up, and then ramped up again – but as far practicable it still remains a ‘safe-fail’ environment.

[An Irish-session is a learning-context, not a performance as such. In the early part of the evening it tends to be slower-paced, with simpler, more consistent tunes; as the evening wears on, and the more experienced players join in and the drink and the adrenalin flow, the pace gets faster, and faster, and the tunes get ‘curly’ with unexpected twists and jumps and key-changes – and that’s when we mere mortals, one by one, drop out in awe, and the real masters get to strut their stuff at full speed… And yet these are often the same guys who sat with us earlier in the evening as we struggled to get our heads and fingers round even one new tune: for this kind of work there’s no ‘class-separation’ between trainees and masters, but everyone here together, all of us with something new to learn.]

One of the most interesting tricks in a context that is known likely to include uncertainty or uniqueness is to hold to the Simple, by simple repetition of the same thing, over and over – and allow the Not-simple to emerge from that, making itself visible by contrast or contradiction. That’s the other purpose of a checklist, for example: we do the same things, to make sure that nothing is missed, but the same process also highlights anything that isn’t right, that doesn’t fit. And that’s when we flip over to the other side of the story – the Not-so-simple…

And the Not-so-simple…

For here, a ‘considered’ approach would describe the typical tactic as ‘act / sense / respond’: do something, to get some kind of information out of the system, and then either withdraw to the ‘Complex domain’ to assess it at more leisure, or collapse back to the Simple. Neither of which will work well when we need to be dealing in real-time with something that isn’t Simple, or ‘known’…

[The classic example here is juggling. In principle, it’s really Simple: throw one ball upward, then another, then another, catch the first one in time to send it back up again, then the next, and so on. Ain’t quite that easy in practice… 🙂

Juggling-balls being what they are, and human hands and arms and timing being what they are, there are many possibilities for variation. And every variation, however slight, has to be allowed for and counteracted in real-time. Yet gravity won’t wait while we work it all out: and it doesn’t take much to have the whole spiral thing further and further out of control, until we lose the plot completely. And then – this being a relatively ‘safe-fail’ environment, start again. And again. And again… Until, yes, we do start to get it right…]

The first rule in this space – and it does indeed have its own bizarre rules – is the same as that etched in large friendly letters on the cover of The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy: DON’T PANIC!

[This is actually much more sensible advice than it might seem. The ‘pan-‘ prefix literally means ‘all of’ or ‘everything’ – hence panorama, pandemic, pandemonium and so on. In classic Greek, the god Pan represented the moment of absolute uniqueness, the zero-point, where everything is possible, and where every time and every place all co-exist at once. If we can’t cope with it, we collapse into the state called ‘panic’ – trying to get away from the madness of ‘here’, which we can’t do because everything and everywhere is already here… But if we can cope with it, ‘hold the centre’ within that space, then by definition somewhere within that infinity of possibilities is the information that we need. Hence that quote in the first Tweet earlier: “Sometimes all you need is just one more good idea.” Which is available somewhere in this space – if we don’t panic.]

The next key is observation – which again takes on a different form here to what it usually does in the other sensemaking domains. It’s particularly well described in this quote (via Ruth Malan – thank you!) from a 2009 article on a keynote by Daniel Pink, published on the Wharton University website:

In another case, medical schools at Yale and Harvard have begun taking students into art museums to increase their observation skills, Pink said. The logic is that in today’s world, a huge amount of medical information is already available online. But learning to observe a patient is something that can’t be memorized from a checklist.

“Doctors have to be able to ask the right questions,” said Pink. “That calls for extraordinary observation skills — the observation skills of a painter, of a sculptor. So, medical schools are taking students to art museums to make them better diagnosticians. And, lo and behold, doctors who receive this type of diagnostic training are better diagnosticians than those who haven’t.”

Pink calls the results of these experiments “a great irony” for the educational system as a whole. “We want to prepare kids for science-oriented careers, so we cut out the arts. Meanwhile, people who are preparing for science-oriented careers are bringing in the arts.”

Other keys here arise from the practices of intentional improvisation, such as described in Keith Johnstone‘s classic Impro, and by more recent business-oriented practitioners such as Mike Bonifer (Gamechangers) and Michelle James (Creative Emergence). For example, two key techniques that have direct business-applications are ‘yes-and‘ and Mask-work.

In ‘yes-and’, we take whatever is given to us – however crazy it might seem at first – and add to it whatever comes up in the spur of the moment. This works well in improv-comedy, of course, but there are plenty of business-contexts where much the same principles will apply: front-line sales, for example. The shoe-retailer Zappos is one example of a highly-successful organisation that has literally built its business by throwing away the script for the call-centre, and instead responding to and with the customer’s needs.

Often the story – or business-story – will only seem to make sense after the event, as Keith Johnstone explains (Impro, p.116):

The improviser has to be like a man walking backwards. He sees where he has been, but he pays no attention to the future. His story can take him anywhere, but his must still ‘balance’ it, and give it shape, by remembering incidents that have been shelved and reincorporating them.

Very often an audience will applaud when earlier material is brought back into the story. The couldn’t tell you why they applaud, but the reincorporation does bring then pleasure.

Business-folk too will often applaud when a story seems to ‘make sense’ in this way – perhaps because it’s made to seem Simple again, although each of the individual threads that make up that story may have little or no real connection with each other, than those that we chose to perceive at the time..

The concept of the Mask is somewhat stranger. An actor puts on a Mask, and in effect enters into negotiation with it. The Mask seemingly has its own choices: different actors who wear it will often find themselves doing much the same thing, though what it does can rarely be predicted solely from its appearance. Even more strange is that whilst wearing a Mask, a performer will be in a kind of semi-trance, working with the Mask rather than attempting to ‘control’ it – in fact the whole process breaks down if there is too much of an attempt to ‘control’.

All of which no doubt sounds a bit abstract, except for one key point. Although improv-theatre Mask-performances will typically use a half-face mask, with the eyes covered but the mouth exposed ‘to speak with one’s own voice’, in fact anything can be a Mask: and that includes a business-uniform, a professional ‘prop’ such as a consultant’s clipboard or doctor’s stethoscope, or even a business-location.

[I remember reading a psychology-study some years back that found that a strong organisational culture could change a new employee’s ‘natural’ behaviour in as little as half a day – almost literally taking on the Mask of the organisation. Helping staff to re-find their own choices in this inadvertent type of Mask-work can sometimes be very important indeed…]

Strange as it is, Mask-work has a number of practical applications in business: for example, almost every profession has its ‘props’ that help establish credibility with clients and others. These processes can also help to get past inhibitions and blocks such as “I’m not creative, I’m not able to work out a new way to do this process”, and so on. Strange, then, but well worth exploring further.

Finally, for here, we can also seed the Chaos, bringing a chosen idea or image into the space as a focus-point for sensemaking and decision-making. This is why vision and values are so important – especially in organisations which, by the nature of the work, must deal with a high level of uncertainty and unpredictability – because they act as a ‘guiding star’ against which the images arising in the turmoil can be contrasted and compared.

[Preparation also plays an important part in this: to use Pasteur’s famous quote, “Chance favours the prepared mind”.]

One of the most difficult parts of this is “trust the process”. Quite often, the ‘guiding star’ will seem to be leading us the ‘wrong way’: it’s essential at this point to trust the ‘star’ rather than our own assumptions, which would drag us back to the over-Simple and its – for here – inappropriate notions of ‘control’. The analogy here is a city with many one-way streets: often the only way to get to somewhere will involve going in what at times will be ‘the wrong direction’, but is actually the quickest way to go.

We do need to be careful what ideas and images we bring into this type of process: in a very literal sense, whatever we bring with us can act as a ‘seed’ around which other ideas and images can coalesce. That can take us in some unexpected and perhaps unwanted directions: yet sometimes – especially after the event – some small seed-image can turn out be the one thing that saves the day. The cockpit voice-recorder of US Airways Flight 1549 provides a fascinating example of this:

Ironically, the Hudson River was in the sights of the two pilots right from the very beginning of the flight.

As the plane lifted into the blue sky moments after take-off, Captain Sullenberger remarked to his first officer: “Uh what a view of the Hudson today.”

“Yeah,” First Officer Jeffrey Skiles said.

There are many other tactics, techniques and processes designed to tackle sensemaking and decision-making ‘on the edge of chaos’, of course, but these should at least give some idea of what needs to happen at business-speed on the ‘Not-so-simple’ side – and also how different most of them are from the overly-simplistic ‘act / sense / respond’ expected in the ‘considered’ approaches to business-sensemaking.

Simple and Not-so-simple – a summary

On the Simple side, the techniques we explored include:

- work-instructions and other ‘rule-like’ processes

- checklists and other ‘sequence/check’ mechanisms

- repetitive patterns to embed ‘body-learning’

- intentional ‘mismatch’ to trigger a move over to the ‘Not-so-simple’ side

On the Not-so-simple side, these included:

- discipline to keep the ‘panic’ at bay, and stay in the ‘Not-so-simple’ space

- open-observation – allowing the context to ‘see itself’ through us or with us

- improv-techniques such as ‘yes-and’ and Mask-work

- ‘seeding the Chaos’ with intention, ideas, images and principles such as organisational vision and values

As in those two Tweets with which we started here, when we’re faced with the unknown at business-speed, intention is the one thing that makes the key difference between a collapse into chaos, and a path to creating something new; and sometimes all we need is just that one more good idea.

That’s it for here. In the final part of this series we’ll explore how to keep all of these in balance as we move back-and-forth across that spectrum between Simple and Not-so-simple. And we’ll also explore the architectures that we need in order to support this type of sensemaking and decision-making at business-speed.

Over to you, anyway – any comments so far, anyone?

Leave a Reply