Four principles – 3: Money doesn’t matter

What’s the real role of money within design for an enterprise-architecture? At the really big-picture scale?

[Apologies, folks: this one’s turned out to be really long, even by my usual standards – but unfortunately this theme is so darn controversial that it really does need the depth of detail here. Sorry!]

This is the fourth in a series of posts on principles for a sane society:

- Four principles for a sane society: Introduction

- Four principles: #1: There are no rules – only guidelines

- Four principles: #2: There are no rights – only responsibilities

- Four principles: #3: Money doesn’t matter – values do

- Four principles: #4: Adaptability is everything – but don’t sacrifice the values

- Four principles for a sane society: Summary

A bit of background first. I’m working on a book and conference-presentation about the role of the ‘business-anarchist’. Part of that work involves exploring some ideas and challenges at the Really Big Picture Enterprise-Architecture (RBPEA) scope – enterprise-architecture at the scale of an entire society, an entire nation, an entire world – and then see where it takes us as we bring it back down again to the everyday.

As I described in the first post in this series, I’ve been looking for fundamental principles upon which long-term viability can depend, under conditions of often highly-variable variety-weather – the changes in change itself. To me, after several decades of study, there seem to be just four of these: there are no rules, there are no rights, money doesn’t matter, and adaptability is everything.

So here’s a bit more detail about the third of those principles for a sane society: the understanding that almost all of the core concepts of money-system, and others of the foundation-stones of present-day economics, are so fundamentally broken that we really do need to rethink the whole structure from scratch, all the way back to its deepest roots. Once we accept the reality of this, it has huge implications for our enterprise-architectures, at every scale – including our day-to-day work with existing enterprises…

Principle #3: Money doesn’t matter – values do

This principle perhaps sounds extreme at first, but it’s actually a direct corollary from Principles #1 and #2. Once we accept that ‘there are no rules – only guidelines‘, then a direct follow-on from that is that we need to challenge the supposed ‘rules’ around concepts such as valuation-in-monetary-form. And, in the same way, once we accept that ‘there are no ‘rights’ – only responsibilities‘, then we likewise need to question the role of money and its various equivalents in the purported-‘rights’ of exclusive-access-to-shared-resources – the so-called ‘property-rights’ or ‘rights of possession’ that lie right at the core of almost all current economics.

There are many distinct themes around this, all interrelated and interdependent yet often operating and impacting at different levels throughout the overall scope. For practical brevity, though, – and for sanity’s sake! – I’ll constrain this to just four of those themes, in approximate order of their accessibility to enterprise-architects:

- the distortions introduced by use of money as a performance-metric

- the distortions introduced by use of money as a system design-guide

- the distortions introduced by use of money as an exchange-medium within a possession-economy

- the fundamental dysfunctionality of any possession-based economy

On money as a performance-metric, we’ll see endless attempts to make this work: performance-based pay, sales-targets, share-price, financial-returns, and so on. The idea is simple enough: if we pay people (a bit) more, they’ll do (a lot) more. It’s so simple that it looks like an obvious ‘no-brainer’: but the reality is that, other than in certain very narrow contexts, it just doesn’t work. For example, as Toby Lowe put it in a Guardian article:

[The NHS review] concluded that “target based performance management always creates ‘gaming’ “. Not sometimes. Not frequently. Always.

To be fair, the problem with ‘gaming’ is not specific to money, but is actually true of just about every conventional performance-metric: people work to the specified target, not to the real need – and, as a result, often miss the real aim and intent of the work. At best, performance-targets distort and deflect away from desired-outcomes – always.

But to make things worse, even the presence of monetary-rewards will itself distort performance, often leading to poorer results overall. There’s been a lot of research on this point, such as from Edward Deci [PDF] in 1971 to Daniel Pink in 2011, and the conclusions have been consistent: past a certain base-level, more money either demotivates (Deci) or leads directly to poorer-quality work (Pink). The only case in which more money does lead to better productivity is when the work itself is so robotic that no real skill is needed and no decisions of any significant kind are required – an extreme type of ‘unskilled labour’ that’s relatively rare in present-day business-contexts.

What does work for motivation is value-based drivers: Pink, for example, describes the importance of autonomy, mastery and purpose, to which I’d add the importance of perceived-fairness in a social context. These are intrinsic motivators – internal to the person, yet often supported by external context – as opposed to extrinsic or ‘external’ motivators such as money or material-reward.

In essence, all purported performance-indicators should be regarded as suspect, or at the very least subject to regular review to mitigate against ‘gaming’. Monetary-based performance-indicators need to be viewed as especially suspect, because of the ways in which they introduce additional dysfunctions and demotivating-factors into the performance-metrics mix.

On using money as a system design-guide, the core problem is similar to that which we saw with purported ‘rights’: at best, a ‘right’ is a declaration of a desired-outcome, without any indication as to how the heck to get there. We see this often in scrambled notions of strategy, such as thinking that an arbitrary target such as “last year +10%” is a viable or meaningful strategy.

Although money introduces its own distortions into this mess, as per above, what we see next is common to all ‘metric-first’ pseudo-strategies. The idea seems to stem from a misunderstanding of the limitations of the linear-paradigm, leading to an assumption that if we can define the end-goal, as the overall output of the system, then we should be able to work directly backwards to identify all of the required inputs to the system. However, the real world just doesn’t work that way: instead, it includes all manner of non-linear and non-reversible transforms that make that easy ideal all but impossible in practice. It’s true that once we do take those non-linearities into account, it usually is possible to make sense of the linkages from the inputs to the outputs – but not the other way round. No matter how much we might want it to, it just doesn’t work.

Just to add to the mess, there seem to be a lot of misunderstandings about the limitations of money as a metric in the first place. In essence, money can only be associated directly with exchangeable assets, for which a somewhat-meaningful price/value relationship can be established. It doesn’t work with non-exchangeable assets, where any attempts at monetary ‘valuation’ will always be problematic, always somewhat-subjective, and always inherently-unstable. Trying to describe everything in monetary terms can often be very misleading, as illustrated in a CBS News item on the ‘United Breaks Guitars‘ incident. The interviewer (at 1:37 on the YouTube video) asks:

Now that’s the guitar in question with you right now, is that correct? … Tell me a bit about this, this is an expensive bit of equipment?

To which the musician/songwriter Dave Carroll replies:

It’s a thirty-five-hundred dollar guitar, but it’s not so much about the money, it’s the sentimental value and it’s a beautiful instrument, I’ve had it for over ten years and played it on all of the [band’s] recordings … some of the songs I’m most proud of were written on that guitar, so…

Yet the presenter still drags it back to money:

You said you spent about twelve-hundred dollars to fix it but it still doesn’t sound the same?

The point here is that, yes, money does indeed matter, to the organisation, and perhaps even more to its investor-beneficiaries, but often not to the customer from whom that money actually comes. Business-organisations often obsess about money, almost to the exclusion of everything else: but it can be serious mistake, because it tends to block out awareness of anything else. The real driver for the customer is compliance to perceived-values, as indicated well by a Tweet that drifted past me this morning:

RT @ManagersDiary: Why customers switch from 1 store 2 another?14% b/c of price,15% b/c of quality & 71% b/c of lousy service.~Tom Peters #business #management

One of the reasons for the obsession about money is that it’s relatively easy to measure: it looks exact, precise, certain. But because of the disconnect between money as an outcome versus value as an input and driver, that certainty can be entirely spurious – and very dangerous. United Airlines found this one out the hard way: in Dave Carroll’s case, their (mis)use of ‘customer service’ as a means to not address customers’ concerns saved them perhaps $500 overall in avoided settlement-costs, but probably cost them at least ten thousand times that much in immediate ‘damage-control’, and many times that again in the longer-term impact on business-reputation.

Another way to look at this is to recognise that focussing primarily on price and cost leads a race to the bottom; whereas focussing on values and value leads a race to the top. It really is as simple as that. So, your choice?

To make full sense of this, we also need a better handle on how markets actually work, and the parts of it to which money and price do and don’t apply. The key here is that we’re dealing with (at least) four distinct asset-dimensions that I typically portray in tetradian-format, the four internal axes of a tetrahedron:

Any resource we work with in any service (and hence an asset within that service) may be any combination of:

- physical asset-dimension: physical objects, physical ‘things’ – independent, tangible, exchangeable, alienable

- virtual asset-dimension: data, information – nominally-independent, abstract/non-tangible, non-alienable, ‘exchanged’ via copy

- relational asset-dimension: relations/connections between people – interpersonal/dependent on both parties, both parties are tangible, non-alienable, non-exchangeable but potentially replicable

- aspirational asset-dimension: anchor-point for ‘belonging’, motivation etc (e.g. as represented by brand) – personal / dependent on both parties; one party tangible, the other (e.g. brand) usually not; non-alienable, non-exchangeable but potentially replicable

Almost all real-world assets that we work with will represent composites of these dimensions. A printed book, for example, is a potential-asset that is both physical (the book itself) and virtual (the information carried in the book); money itself is a composite of virtual (information) and aspirational (the social belief in the value of money), with price as an indicator of that information and belief as applied to some other asset. Or, to apply this to Carroll’s guitar, it’s obviously physical, but to Carroll himself also very much aspirational (“sentimental value … beautiful instrument … had it for over ten years … songs I’m most proud of were written on that guitar”).

And the key here is that price and money only make sense with exchangeable-assets. They don’t make sense with the non-exchangeable asset-dimensions. And since most real-world assets incorporate some mix of exchangeable (physical, virtual) and non-exchangeable (relational, aspirational), things can get really messy if we try to apply conventional money-metrics to everything.

[Okay, there’s an added complication here around pricing in relation to ‘scarcity-value’ and ‘desire to possess’, which in effect is more in the aspirational-dimension: yet when we look deeper into the dysfunctions of possession-based economics, we’ll see it’s actually a special-case which, if misunderstood – as it usually is – can be very dangerous to the organisation. To make sense of why it’s so dangerous, though, will need a lot of extra detail, which for now is probably best left to a separate post?]

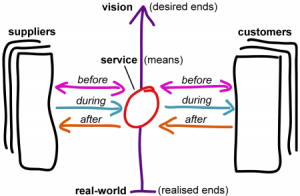

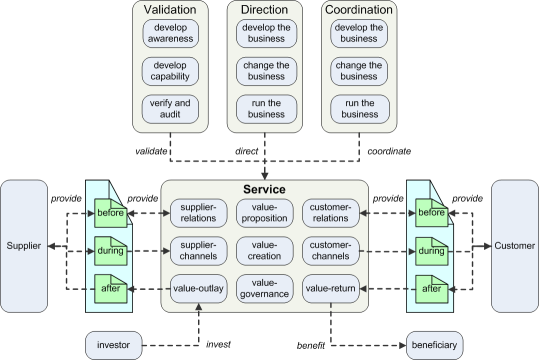

When we look at what happens in the service-cycle within a market, we can see this strong distinction between interactions that work primarily with the non-exchangeable asset-dimensions (aspirational and relational – trust, respect and connection), both before and after the transactions that work primarily with the exchangeable asset-dimensions (virtual and physical – information and ‘things’). We can summarise the typical ‘before’, ‘during’ and ‘after’ sequences in visual form:

Or, with slightly different emphasis:

If we think of a sale in terms of the classic project life-cycle (Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing, Adjourning), or the same in the equivalent Five Elements sequence (Purpose, People, Preparation, Process, Performance), then monetisation of the sale occurs at the ‘completion for self’ transition between the end of Process (in other words, end of transaction) and the start of Performance (benefits-realisation and action-review). Especially over the longer-term, the service depends on the whole cycle: all transactions and interactions.

Yet when people become over-focussed on monetary-return, they tend to stop the cycle immediately monetisation occurs – immediately payment has been made – and rush back to the Preparation phase to try to set up another transaction. If only that short-cut version of cycle is used, it does deliver better short-term return, but at a cost of a subtle yet often rapidly-accelerating loss of connection to the non-transaction parts of the service-cycle: loss of trust, Purpose, values, People, policies. This eventually kills the cycle stone-dead, seemingly ‘without warning’, because the non-transaction parts of the cycle aren’t even visible to this stripped-down over-‘lean’ service. In visual form, this is the ‘quick-profit failure-cycle’:

In short, an over-focus on monetary-return in a service is not a good idea… And although that return may be the only aspect of the service that is of interest to some of the service’s stakeholders, the service itself won’t work for long unless all of its aspects are fully included and work together as a unified whole.

We also need to be aware that, again, we can’t use extrinsic-motivators such as money to try to ‘control’ the non-exchange interactions – a point that should be self-evident if we put together two old song-themes around “Money can’t buy me love” and “Love is what makes the world go round” (not money, we may note! 🙂 ). There’s a certain bleakness in a literal translation of the word ‘compensation’ as ‘an against-thinking thing’ (‘con’, against; ‘pensar’ to think): money might distract us for a while from relational or aspirational loss, but it doesn’t keep the hurt or pain at bay indefinitely. There are some subtle yet all-too-real issues here for customer-service and the like that are easy to miss, yet definitely should not be missed if we want to avoid our own ‘United Breaks Guitars’…

On money as an exchange-medium within a possession-economy, the role of money is that it provides a means to bypass one of the inherent flaws in point-to-point barter-exchange – that if we have something to offer for exchange, and the only people who want it don’t have anything to offer that we want in return, then we’re all stuck, unable to engage in ‘economic exchange’. To break the deadlock, money represents a kind of ‘universal barter-thing’ that can be exchanged with anyone for anything within its scope; the principle of ‘pricing’, or ‘price-value match’, is then used to guide and govern ‘fair exchange’.

It’s a nice idea, and potentially a very neat solution to a real problem in a possession-based economy: but unfortunately, as we’re all now discovering to our cost, it not only doesn’t work well in practice, but the feedback-loops in those flaws are now trending beyond any possible control or recovery. Although they may seem outside of the remit of enterprise-architects at present, these are really serious problems that are going to start to hit just about everywhere, very hard indeed, Real Soon Now: we need to be aware of them, and work out as far in advance as we can about what we can do to mitigate their effects.

One obvious example is that the concept ultimately depends on ‘fairness’ in price-value match. Yet many business-models actually depend on price-value mis-match: on others not knowing what a ‘fair price’ would be, or in a context of power-asymmetry such as a monopoly or cartel where others are not able to negotiate ‘fair price’ – otherwise known as ‘legalised theft’. As per the ‘quick-profit failure-cycle’ above, this will no doubt seem profitable for quite a while – but can collapse in an instant, often in kurtosis form, as soon as the scam is exposed or the cartel can be bypassed.

Other business-models are equally dependent on creating ‘externalities‘, where costs (‘cost’ in many different senses here) are avoided or offloaded onto others: environmental-costs and tax-avoidance schemes are two increasingly obvious examples of this. When the externalities are blocked or returned, the business-model may well become non-viable. (Whole-of-enterprise architecture-assessment can be an extremely important tool here, in identifying such externalities and their potential impacts on an organisation’s business-models or overall operations.)

The other key issue is that the whole concept of a currency depends on trust, both as trust in the effective value of the currency itself as a medium and moderator of exchange, and trust in each of the respective players within the scope of that currency. In effect, in a ‘rights’-based context such as a possession-economy, money represents ‘personal ‘rights’ to respective share of shared-resources’: if trust in the currency is lost, the sense of available-access to ‘fair share’ of shared-resources is also either lost, or becomes unavailable, and the entire economy then breaks down. In practice, for almost all ‘fiat-currencies‘ linked to the ‘global economy’, we may well be either close to or beyond that point already: it’s probable that it’s only being held together by a large amount of ‘smoke-and-mirrors’ bluff, lack of apparent viable alternatives, wishful-thinking and sheer inertia: the long-term or even medium-term outlook is not good at all.

This has been made much worse by a potentially-lethal shift in global-banking and global-finance. In the same way that the role of insurance, in a money-based possession-economy, is to help in managing the financial aspects of risk, the role of banking and suchlike should be the management of the financial aspects of opportunity. Instead, over the past few decades, their focus has shifted to secondary or even tertiary gambling with ‘other people’s money’, leveraging the fact that, as an asset that in essence is an imaginary and largely-arbitrary number relating to ‘information about a belief’, money is potentially infinite, which therefore implies that infinite profits can also be made by manipulating that information-asset.

However, the real-world exchangeable-resources, to which that potentially-infinite money-number purports to assign exclusive-possession ‘rights’, are most definitely not infinite – hence the runaway feedback-loops in the banks’ global gambling-schemes represent rapidly-accelerating dilution of everyone else’s ‘rights’ to those resources. If we then couple this with an increasing awareness that the banks and suchlike are literally inventing ‘money’ out of nothing – typically via mechanisms of assigned-debt – and then assigning the resultant ‘money-rights’ to themselves, we again have a context where belief in ‘fairness’ of the overall money-system is evaporating fast: and with it the mutual-trust upon which the whole money-system and its underlying economic-system ultimately depend. Again, the outlook here is not good at all.

As a simple illustration, consider the effective value – not just price – of a house. For almost a century, the price of a house (or other living-space) that one could afford had been relatively stable, at around three times the respective person’s annual salary. During that time, the effective value of that house, in terms of services delivered by the house itself, had risen considerably: water, sewerage, drainage, bath, toilet, lighting, electricity and more would all have been added over that time, together with a lot more available-space and available-privacy. In other words, the price-value relationship had shifted considerably in most people’s favour – often referred to as part of ‘quality of life’.

About three decades ago, though, there was a lot of pressure applied by certain groups to get enacted a crucial shift in (de)regulation: in particular, a near-complete removal of limits on banks’ allowable liquidity-ratio of real-assets to largely-imaginary ones – which released them to ‘lend’ almost as much as they liked, hugely increasing the apparent profit but also hugely increasing their largely-unacknowledged risk. The result was that effective house-prices rocketed, first to around ten times nominal salary, and then stabilising somewhat – after the ‘unexpected’ yet all-too-predictable ‘sub-prime’ crash – to their present level of around five to six times nominal salary. Which in practice, after adjusting for tax and debt-interest payments, typically represents the entire life-income for the respective person for some twenty to thirty years. Which is simply not viable in the longer-term – especially as house-sizes are dwindling, further reducing the effective price-value (mis)match, and thus the perceived value of the entire housing-management system. Once again, not a good outlook here – yet actually an inevitable outcome of the inherent flaws of a money-based economics.

To put it bluntly, the whole fiat-money system is broken, probably worldwide, and by now almost certainly beyond feasible repair.

Once people understand this point, the reflex response seems to be to try to build some kind of ‘alternative-currency’ model. There are now literally tens of thousands of these schemes, scattered all over the globe, in varying levels of implementation from vague-idea to real-life practice. Most of them, it seems, manage to replicate most or all the disadvantages of the existing money-system without adding much if any real advantage at all. At best, they mitigate some of the worst excesses by constraining the respective economy to a very small local context where strong direct interpersonal relationships of trust are both feasible and available – and in which introducing some kind of ‘currency’ is an unnecessary overhead that in practice is more of a hindrance than a help.

What I’ll admit drives me crazy about this is that all of those attempts to create ‘alternative-currencies’ are merely a vast waste of much-needed thought and effort – because none of them will work, especially over the longer-term. What all of these groups seem to miss is that the problem isn’t in the design of the currency: it’s the concept of currency itself that doesn’t work.

And the reason it doesn’t work – and can’t be made to work – is because the real problem lies quite a lot deeper. Currency is just an overlay on top of barter; and barter is just a means to manage exchange of possessions. But what if they aren’t ‘possessions’? Whose possessions are they, really? And what is ‘possession’ in the first place? Without a better understanding of those questions, everything else is just futzing-around on the surface. Or, to put it in visual form:

Which brings us to the last theme here, the fundamental dysfunctionality of any possession-based economy. Notice that key-word in the diagram above: ‘property-rights‘. Yep, what we’re dealing with here are purported ‘rights’ – and as we’ve seen in the previous post in this series, we can only make an enterprise or economics work once we understand that there are no ‘rights’, only responsibilities.

The whole concept of possession is actually a two-year-old’s view of resource-sharing – or, more accurately, of not-sharing, a raging scream of ‘Mine!!!‘. The ‘need’ to (seem to) possess is a direct driver for paediarchy – and possession-economics is its direct outcome. It’s an arbitrary assertion of immediate, personal and absolute ‘right’ to withhold a resource from others, regardless of the needs of any others either in the present or elsewhen.

[There’s also ‘anti-property’ and ‘anti-possession’, where an unwanted resource is dumped onto others to resolve: think of a two-year-old’s reflex means of dealing with an ice-cream wrapper… We can also illustrate this with a bleak old joke about beer-cans. It seems people can easily carry a six-pack, or even a full twenty-four-can slab, any distance at all, up a mountain, into the desert, or down into the depths of the forest; but as soon as a can is empty, it apparently becomes impossibly heavy to carry any further, because it’s immediately abandoned on the spot. Presumably the only possible explanation for this is that beer has negative-weight…?]

Ultimately, possession always implies dispossession of others: there’s a lot of bleak sense in the old anarchist slogan that ‘all property is theft’. Possession-economics, almost by definition, will also always incorporate some element of violence, ‘propping Self up by putting Other down’. And both possession and anti-possession, almost by definition, will always incorporate some element of abuse, ‘offloading responsibility onto the Other without their engagement and consent’. All of that is actually inherent in the concept of possession itself. It should be self-evident, I think, that it’s not a good idea to try to build a viable economics on top of something that’s that dysfunctional?

And yes, it gets worse. The ideas behind possession-economics can sort-of be made to just-about work for inter-group transactions – in other words, trade between groups that don’t interact much and don’t much need to trust each other. It sort-of works if we focus only on the ‘now’, and ignore the impact of longer timescales – particularly in relation to non-self-renewable resources that are mined rather than farmed. But it does not work for intra-group interactions, because there’s always someone whose work or life will revolve around non-exchangeable resources, or who – as is the case with children or active parents or the elderly – won’t have access to ‘tradeable’ resources or skills in any case.

[If this isn’t obvious, try running your own household on strict monetarist lines, in which every interaction must have its own monetary price… I’ve often thought there’s excellent material for a family-comedy there: I really must write that screenplay sometime! 🙂 ]

All possession-based economies will always trend towards some variant of The Worst Possible System, in which a society’s resources automatically migrate away from wherever, whenever and for whomever they’re most needed. If this isn’t obvious, do a simple cross-map of the likely resource-needs at each stage of a somewhat-stereotypic life-cycle, and the probable availability of those resources in a possession-based economy at each of those stages. The result will demonstrate just how inefficient, ineffective and dysfunctional our ‘normal’ economics really is:

- teenager: not much needs (though huge wants, of course!); not much resources available

- first leaving home: huge resource-needs (to equip a new household); little to no resources (most likely a minimum-wage job at best)

- moving in with a partner: negative resource-needs (because you now have two of everything); much greater resource-availability (two probably-higher incomes, lower costs from shared-resources and economies-of-scale)

- children arrive: huge resource-needs (all the costs of a new and growing child); much lower resource-availability (one partner working full-time with child, hence only one monetary-income)

- children at school: resource-needs somewhat stabilised; probable return of matching-income (as the parent-partner returns at least to part-time paid-work)

- move to another city for a better job: huge upward-spike in resource-needs (find a house, pay for the legals and the move, find new schools and equipment for children); steep downward-spike in resource-availability (because the other partner’s job either ends or incurs huge travel-costs)

- children fully leave home: resource-needs drop; resource-availability probably at highest ever (both partners in senior-level roles with higher-incomes, house-payments also probably ended)

- initial retirement: resource-needs reduce further, or even negative (sell off and move to smaller house); resource-availability very high (first-stage pension plus state-benefits plus sale of former larger-house)

- later retirement: resource-needs rise steeply (particularly for medical care); resource-availability drops steeply (particularly with impact of inflation on fixed-income assets)

Throw into the mix an example of illness, for example, or divorce: we’ll see exactly the same pattern there. Whichever way we play it, in a possession-based economics, whenever we least need resources is when they are most likely to be available, and whenever we most need resources is when they’re least likely to be available. In other words, an almost perfect mismatch – the least efficient and effective system we could possibly devise. The dysfunctions of money-based economics are just an overlay on top of that mess: those dysfunctions do make it a heck of a lot worse, but removing money alone from the system still wouldn’t make the mess work.

As with any badly-designed system, it’s left to the users themselves – all of us – to bridge across the gaps somehow, and to kludge together various workarounds to make it just-about possible to use. Hence the whole mess of savings and loans and pensions and taxes and benefits, to try to time-shift resources forward or back from when they’re currently available to when they’ll actually be needed. But by definition it’s a constant struggle against the tide, or against gravity, because the nature of a possession-economy is that it will automatically revert to The Worst Possible System wherever it has any chance to do so.

The societal overhead of these kludges is huge: when we add it all together, it’s probable it’s already at least a third of the entire economic effort, and still rising fast. It’s long since gone past the point of diminishing-returns: it’s now an overhead that we simply cannot afford.

[And what’s so frustrating is that all of it is completely unnecessary, because in principle we could replace every single monetary transaction with the one phrase “What do you need?” Yes, that would no doubt be inefficient in places; yes, no doubt it would be wasteful in some contexts; yes, no doubt there would be people who would game it, and in some cases game it hard. And yet it’s not difficult to derive at least ball-park figures for the impacts of those inefficiencies: and when we add them all up, they still come out a lot less than what it’s costing us now to carry the immense overhead an ineffectiveness of the money-economy. An interesting point to ponder, perhaps?]

In practice, the only way that this mess can be made to seem to work is to run it as a pyramid-game – hence the endless obsession with ‘economic growth’, because that’s the only way to hide the fact that this is a pyramid-game. But the blunt reality is that we can’t have infinite-growth on a finite planet: and when a pyramid-game hits its limits, its only remaining option is to cannibalise itself into oblivion. As far as we can tell from economic-histories – the periods of fiefdoms, kingdoms, colonial-empires, economic-manipulation via ‘globalisation’ and so on – this particular pyramid-game of the possession-economy has been running for perhaps five thousand years or so, but it started to hit up against real limits perhaps fifty years ago, and there’s all too much evidence now that it’s well into its final self-cannibalisation phase. In short, not good…

The catch, of course, is that this is the only economic-system that most people know or understand, which – given the ways people usually react under severe stress – almost certainly means that most people will try to cling on to it and pretend that it ‘is’ working, until way too far past any feasible ‘use-by’ date. And anyone who questions this literally-insane behaviour is themselves likely to be labelled a lunatic, or a ‘terrorist’, or worse – sometimes much worse… so we do need to be careful here.

But to be blunt, there’s no way around this fact: there is no way to make a possession-based economy sustainable. It can’t be done. Whatever we do, and whichever way we try to twist it to make it seem to work, any possession-based element in an economics will always bring us back into the kind of mess we’re dealing with here, and ultimately will always cause the failure of that economy. It really is that fundamental a problem here.

As I see it, the only feasible way out of this mess is to reject the purported ‘rights’ of possession (because there are no rights), reject the purported ‘rules’ around ‘rights’ of possession (because a ‘right’ is a purported ‘rule’, and there are no rules), and instead rebuild the whole darn lot from scratch, around what does work – guidelines for interlocking mutual-responsibilities. Which is going to be a huge project: probably a century or more, overall, on a truly global scale. But we need to get started now, because that process of self-cannibalisation is already well underway, and time is running out to lay the foundations for a viable alternative. And whole-scope enterprise-architecture is probably one of the few disciplines that has the tools available to start to work on those foundations – which is why this discussion here about the role of enterprise-architecture is perhaps a lot more important than it might at first seem.

One interesting aside here is that in a responsibility-based economics, the entire notion of money is irrelevant: hence the future of money is that it has no future. Which, given how much so many people obsess so much about it right now, is perhaps kinda amusing? 😐 Oh well…

Implications for enterprise-architecture

Anyway, at this point we do need to bring all of this back down out of the future and big-picture, and explore the practical implications in our everyday enterprise-architectures of right here and right now. If money doesn’t matter – but values do – then how do we express that in practice, in architecture and system-design?

Let’s return briefly to those four themes:

- the distortions introduced by use of money as a performance-metric

- the distortions introduced by use of money as a system design-guide

- the distortions introduced by use of money as an exchange-medium within a possession-economy

- the fundamental dysfunctionality of any possession-based economy

Of these, most of us won’t have any real chance to tackle either of the latter two themes at present – but we need to be aware of them at all times in our architecture-work. We do need a clear understanding that the overall money-system not only doesn’t work but can’t work, and likewise for the possession-based concepts that underlie it: but just do what we can about them, when we can do it, is probably more than enough to cope with for now.

As enterprise-architects, we are quite likely to be able to do something about the first two themes. On using money as a performance-metric, the quickest summary is “don’t do it” – and wherever practicable, dissuade others from doing so too. The only place where money can and ‘should’ be used as a performance-metric is in the organisation’s financial-accounts: using monetary metrics anywhere else in a system will cause dysfunctions in that system, and/or ‘gaming’ of that system, and creates variously-high risks for the overall organisation. Don’t do it: simple as that, really.

Much the same applies to using a money-focus as a system design-guide: the short summary is again “don’t do it”. Instead, keep the focus on values, and allow the money-oriented concerns arise from that, rather than attempting to do it the other (wrong) way round.

There’s a lot of material on this weblog about how to do that, particularly via modelling with Enterprise Canvas. The catch is that there’s so much on this blog, that I’ll admit that finding the information you need can sometimes not be all that easy, so I’ll give a quick(ish) summary here.

Enterprise Canvas modelling begins with the assertion that everything in the enterprise is or represents a service. (To be more pedantic, we can describe everything as if it’s a service: that distinction is subtle but sometimes important.) And if everything is a service, we can therefore model everything and anything in essentially the same way.

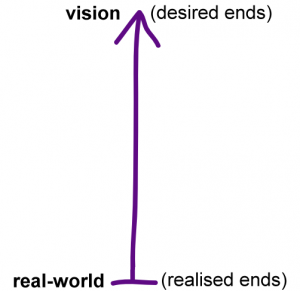

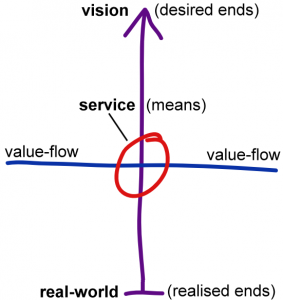

We start off with a simple comparison between desired-ends – what we want to achieve – versus realised-ends – what we’ve managed to achieve so far. The tension between these two creates a desire for change – an emotional driver that is the direct source for the literal ‘enterprise‘, as ‘the animal spirits of the entrepreneur’. The desired-ends are described as the vision for that change, whilst the enterprise-values are the qualitative criteria to guide the change.

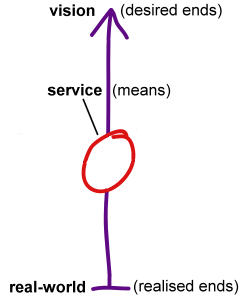

To put it at its simplest, a service is a means to deliver or act towards a vision (desired-ends) in accordance with the values. In effect, the values determine the overall success-criteria for the service and its service-delivery.

A service serves – which is why it’s called a service. And what it ultimately serves is the vision, and the values that underpin that vision. In practice, though, it can rarely serve that vision all on its own: it needs the help of other services to reach towards that vision. Services assist each other towards their respective visions by exchanges of value – which is why this pattern of exchanges is also called a value-flow:

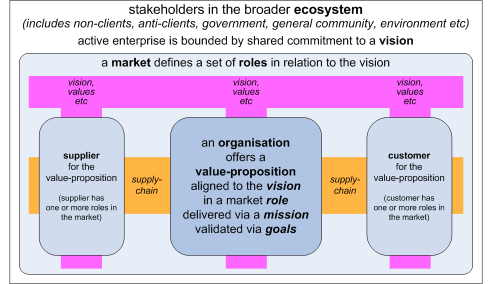

Services connect with each other through a value-proposition, which describes needs (to consume services from others) or capabilities (to provide services to others), in relation to the service’s own vision and values.

In effect, the value-proposition provides a reason for services to connect with each other: through the value-proposition, the services can identify that their respective visions and values have close enough relationships with each other to indicate that exchange of assets and/or services would be worthwhile.

To give a practical example, assume that one organisation provides the services of a retailer of paint:

- Its vision relates to the ‘big-picture’ context: for example, ‘creating beautiful spaces for living’, with implicit values of quality, beauty, relaxation, satisfaction.

- Its value-proposition indicates to potential suppliers (service-providers), such as paint-manufacturers, that it will need supplies of paint, in alignment with those values.

- The same value-proposition indicates to potential customers (service-consumers), such as tradesfolks or home-decorators, that it can provide them with paint, in alignment with those values.

- This organisation’s added-value is that it provides immediate-availability of paint, and can assist customers in finding the most appropriate paint for their needs.

We can expand this outward to describe the drivers and relations between the various stakeholders of the service (here described as ‘an organisation’), all the way out from direct-transaction relations with suppliers and customers, to the more general interactions and potential-transactions in the marketplace, to the interaction-only relations with others in the broader ecosystem that shares the same overall vision and values:

Every interaction or exchange involves some form of assets, built up from those dimensions described earlier: physical, virtual, relational, aspirational.

And as we saw from the service-cycle above, there are interactions that happen both before and after the main exchange-transactions, which we can summarise visually as follows:

We can summarise these interactions as follows:

- before: primarily aspirational and/or relational asset-dimensions (reputation/trust, respect/relationship, conversation) – establishes connection via shared/compatible visions and values, and agreement on conditions for exchange (e.g. service-level agreement)

- during: primarily physical and/or virtual asset-dimensions – the respective ‘goods and services’

- after: primarily relational and/or aspirational (satisfaction, reaffirmed trust) plus any asset-types required for completion (such as monetary payment) to ensure and verify ‘fair exchange’ in accordance with the agreed conditions for exchange

The relations in the ‘before’ phase tend to show a lot of back-and-forth interactions; in the ‘during’ phase, primarily from provider to consumer; and in the ‘after’ phase, primarily from consumer to provider – so as to balance up the overall transaction-exchange.

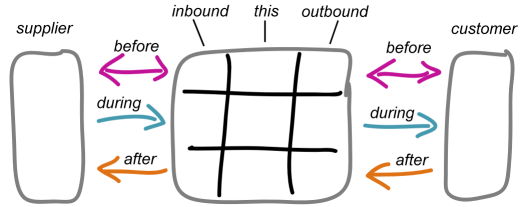

Given all of this, we can identify a kind of three-by-three matrix of abstract ‘child-services’ within the service, each dealing with one aspect of those two dimensions:

- task: supplier-facing (inbound), value-add (this), customer-facing (outbound)

- sequence: setup (before), transaction (during), completion/follow-through (after)

Or, in visual form:

We can assign meaningful labels for each of these ‘child-services’. On the ‘outbound’ customer-facing side especially, these align quite well with the cells of Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas:

And if we crosslink it with the Five Elements sequence (as summarised in the ‘quick-profit failure-cycle’ diagram above), and put the internal child-services to the left and outward-facing child-services to the right, we end up with a kind of zigzag of interactions and responsibilities and drivers that show the whole sequence of the service-cycle in relation to the abstract-structure of the service itself:

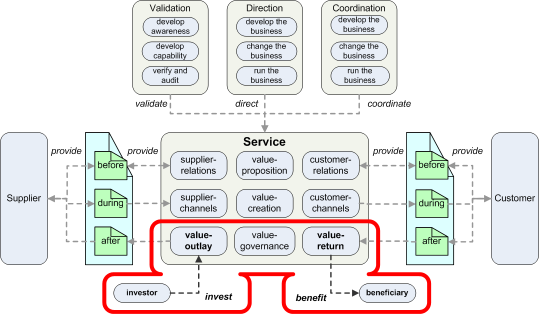

But where does money come into all this? If – as we’re told, ‘money makes the world go round’, or that ‘making money’ is the only reason that the organisation exists, why isn’t it shown as the centre of everything in this description?

The short answer is: it isn’t. Not in most contexts, anyway. It’s true that in a few special-cases – such as banking and finance – the ‘item of value’ being exchanged in the ‘during’ transaction-phase is money, but otherwise that’s about it for that part of services. It’s also true that in a money-based possession-economy, discussions about monetary-price will usually be included in the ‘before’-phase interactions that set up the conditions for the transaction-exchange; and completions, in the ‘after’-interactions, would typically include an asset-exchange called ‘monetary payment’ to complete the ‘fair-exchange’. But that’s it: nothing else.

We’re enterprise-architects, not financiers. Yes, we need to be aware of money, and the impacts of the money-economy on our systems and system-designs: but for our work, our purposes, it should not be seen as ‘the centre of the world’. In a service-context, and in system-design, money should not be seen as anything special, anything central: to be blunt, it’s really not all that important. For example, in a barter-based service-exchange, money wouldn’t figure anywhere in it at all; and in a service-exchange that revolves primarily around relational- or aspirational-assets – such as in the first stages of dealing with a customer-service complaint – there probably wouldn’t even be any barter either. Yet there’s always value, in relation to values, striving towards the enterprise-vision: that’s what drives the service-cycle, and hence that’s what drives the design. Which is why, as architects and system-designers, we must design primarily with the awareness that, in most aspects of a system-design, money doesn’t matter – values do.

Unfortunately, a great deal of first-hand experience indicates that a lot of people still won’t believe me on this. Surely money must come into it somewhere? Especially for a for-profit business? Otherwise where’s the profit? – how does that happen?

Sure, that’s valid enough – those are questions that do need to be answered. And we can answer them – but only if we expand that view of the service to include a broader set of inter-service interdependencies that aren’t really part of the individual service itself:

To make sense of this, we need to take a closer look at what happens in the ‘after-transaction’ flows – shown above as the right-to-left ‘past’ flows.

To balance out the ‘fair-exchange’ from the main-transaction, the service-consumer (customer) typically provides some form of returned-value – a monetary payment, for example – which in conventional business-models is usually described as revenue. A service typically includes specific child-services – for example ‘Accounts Receivable’ – to handle this incoming ‘value-return’ flow.

On the other side – here, the left-hand side – this service is itself also a service-consumer, and hence likewise typically provides some form of returned-value to its service-provider (supplier). In conventional business-models this is usually described as cost. A service typically includes specific child-services – such as ‘Accounts Payable’ – to handle this outgoing ‘value-outlay’ flow.

Somewhere in the middle between these two, we need some kind of governance to keep the balance between incomings and outgoings, revenue and cost. That’s a typical responsibility of line-management for that respective. There’s often a need for management-information to pass between the layers, dealing with practical issues such as scheduling and aggregation, and that’s usually bundled in as part of the same value-governance child-services.

Beneath that, external to the service itself, the service may have investors and/or beneficiaries. Technically speaking, these are also inter-service relationships with respective exchanges and flows, much like those with suppliers and customers. However, these are kind of backwards to the main flow: investors put value (investment) into the service’s value-outlay flow, and beneficiaries extract value (dividend) from the value-return flow. Note, though, that there are several very important complications here, including:

- the value that is invested and/or withdrawn as dividend may be of any asset-type, and hence may or may not be in monetary form – even in a nominal for-profit organisation

- the value that is invested will usually not be the same as in the main-transaction value-flow – for example, investors invest money, but customers receive paint – hence it’s crucially important not to mix up the different forms of value

- the value-forms received by beneficiaries may not be the same as the value-forms invested by investors

- investors and beneficiaries may not be the same entities or people

- governance-mechanisms will be needed to ensure that there is full balance across the overall interactions and ‘fair exchange’ for all of the service’s investors and beneficiaries

The governance-role is typically assigned to those same ‘value-governance’ child-services – though often with assistance of and/or delegated ‘upward’ to the external (to this service) ‘direction’ services.

None of that governance is trivial: but it’s invariably made a lot harder by mistaking money for ‘value’ – or, worse, thinking that money is the only form of value in play. Doing the latter creates a context in which all of the non-monetary investment is ignored, yet all beneficiary-dividends converted to monetary form, and then provided only to those beneficiaries who can claim a monetary interest – which, in effect, institutionalises into the system-design a systematic theft from non-monetary investors and non-monetary would-be beneficiaries. It’s still very common – most often from ignorance rather than deliberate ‘malice aforethought’, it should be said – but it’s not a good idea…

On top of that, we have several very different types of investor-beneficiaries, ranging from the symbiote – committed to supporting the service – to the scavenger – committed only to their own interest, regardless of what damage that might cause elsewhere. Unfortunately most of the current shareholder-models privilege these types in the exact opposite order to what we most need: the scavenger usually has highest priority, the symbiote the lowest. Yet another direct outcome of the dysfunctionalities of a ‘responsibility-free’ possession-economy…

Overall, architecturally speaking, there’s a vast amount that we need to know about any service in order to ensure its viability. In Enterprise Canvas, the simplified summary-checklist for viability of service-interdependencies looks like this:

And of that, in most cases, the only part that has anything much to do with money – even in a for-profit organisation – is in some subsections of the region outlined below in red:

For everything else, in almost every other aspect anywhere else in the design and operation of the service, money doesn’t matter – but values do.

More to the point, if we try focus too much on money in any of those other areas – or worse, try to force-fit them to monetary assumptions or a monetarist view of value – then the service will fail, especially in the longer term.

As an enterprise-architect or system-designer, it really is as simple as that.

Your choice?

Hi Tom,

I agree and disagree with a lot of things you say in the article. That makes it hard to respond (on Twitter or here). Part of me thinks that the problem is more complicated than you are sketching and part of me thinks that the problem is less complicated. So for me it is still the question if we can design a solution without creating similar or worse problems or that there is an achievable safe way out.

My worse-case scenario is that nature’s prefrontal cortex experiment is a failure and to quote Einstein: “You can’t solve a problem with the same mind that created it.”

My best-case scenario is that the problem is not money and/or possessions and responsibilities is not the solution but the problem is the financial-economic system that we Dutch invented with the VOC (around 1600 and a few years later we Dutch had the first bubble implosion/market crash) and replacing that system is perhaps easier to achieve than replacing possession with responsibilities.

So I’m still in some kind of exploring state between those two scenario’s.

Hi Peter

You said elsewhere you’re still reading this, so will await your later comments (if any) on the whole. In the meantime, two points for response:

“nature’s prefrontal cortex experiment is a failure” – please don’t fall back to the ‘it’s human nature’ excuse! 🙂 Lizard-brain and empathy and the two-year-old’s possessiveness and deep altruism are all in ‘human nature’ – and to a very significant extent it’s up to us as to which aspects of of that ‘it’s all human nature’ we would choose to emphasise or de-emphasise. It’s a choice – not a fixed matter of fate. And if it’s a choice, then there are architectures that already exist to support that kind of choice, right out to the ‘big-picture’ level – which means that we have the option to change those architectures: that’s a choice too. (I’ll do a separate blog-post on that somewhen soon.)

“the financial-economic system that we Dutch invented with the VOC)” – national-pride (or national-self-blame? 🙂 ) is all fine and such, but I think you’ll find that the mess originates quite a long way further back than that (to Babylonian times at least), and goes a lot deeper, too (to the roots of paediarchy in how we choose to placate the two-year-old’s possessive temper-tantrum). As I said in the post above, the current financial mess is really just a surface-level phenomenon, and fixing even that huge mess is really little more futzing-around at the edges. Sure, the current financial mess is nasty enough, but the real mythquake around possession itself will make it pale into insignificance by comparison – and the damage of the mythquake will almost certainly be non-recoverable unless we start developing some serious mythquake-preparedness right now.

That’s what all of this series of posts has been about: preparing for an utterly-inevitable period of massive foundational change. Hence not just enterprise-architecture for an organisation or two, but getting into practice to do the same kind of work at a fully global scale: Really-Big-Picture Enterprise-Architecture.

“You can’t solve a problem with the same mind that created it” – yep. Which is why I’m asking you to think a lot deeper than just ‘human nature’ and ‘Dutch financiers’ – because that surface-level thinking is the kind of mindset that created this mess in this first place.

Over to you? 🙂

Hi Tom,

I think I’ve already said it before in a comment on one of your other articles a “long time” ago (I think we disagreed also at that time on this point) that I believe what Dick Swaab is saying is true: “We are our brain”. Basically he argues (e.g. at conferences like http://www.iscoms.org/programme/992_neurobiology-we-are-our-brain.html) that we may think that we have a free will and free choice but in reality those are limited by the capabilities and/or disabilities of our brains, and the vevelopment of individual brains are or can be influenced by all kinds of (genetical, biological, chemical) internal and external things . So free choice/will is not the same set or range of options for everybody. For me this is not an excuse but a limiting fact of life.

If I think of a society not based on possessions but based on responsibilities then I immediately think of issues like the tragedy of the commons and negative responsibilities as described by Hardin e.g. in http://www.garretthardinsociety.org/articles/art_who_benefits_who_pays.html

So I’m still asking myself the question: is what you proposes achievable and will it really result in a better society. And if the answer is yes on both questions, what steps should we take to arrive from here to there?

But at the moment I’m not convinced that yes will be the answer to both questions mainly because I think that in the end we’ll always be limited by our own brains unless evolution or some “design trick” improves our brain so that our sharing/empathy capabilities will increase.

I don’t say you are wrong but just that I come from a different “brain” point of view (which may be wrong, but at this point that is how I look at our brain capabilities based on a lot of reading about the working and the plasticity of the brain)

BTW I’m just pre-occupied with the VOC, so it is easy to refer to that time for me 🙂

Peter,

“If I think of a society not based on possessions but based on responsibilities then I immediately think of issues like the tragedy of the commons”

To keep to a Dutch example, I was thinking more of ‘polder-democracy’ – if we’re farming on the polder, we have to get rid of our excess-water onto our neighbour’s farm, who has to shift it onto their neighbour’s farm, and so on, all the way over the dike. We may not like our neighbours, but unless everyone understands and lives by their interlocking mutual-responsibilities, everyone‘s farm will be in trouble. (Given that people often don’t like each other, there’s often a real need for the water-bailiff to mediate in disputes between neighbours, and also to deal with collective ‘tragedy of the commons’ risks; and beyond that, the role of the Rijkswaterstaat, to make sure that the drainage- and transport-infrastructure all works – all of which are other interlocking responsibilities… 🙂 )

“I come from a different “brain” point of view”

Hmm… All I’d say to that is that, as in all architectures, we need always to maintain awareness of the system-as-whole: beware of ‘brain-centrism’! 🙂

Hi Tom,

Beware of thinking that the system-as-whole-centrism is the most important “centrism” :-):

“Becoming an effective systems thinker also requires the rigorous and disciplined use of scientific inquiry skills so that we can uncover our hidden assumptions and biases. It requires respect and empathy for others and other viewpoints. Most important, and most difficult to learn, systems thinking requires understanding that all models are wrong and humility about the limitations of our knowledge. Such humility is essential in creating an environment in which we can learn about the complex systems in which we are embedded and work effectively to create the world we truly desire.”

Quote from “All Models are Wrong: Reflections on Becoming a Systems Scientist” at http://web.mit.edu/jsterman/www/All_Models.html

Hi Peter

‘System-as-whole’ isn’t a centrism! 🙂

(To quote a certain well-informed-and-intelligently-thinking-and-generally-all-round-clever-person-that-you’ve-probably-never-heard-of [i.e. me 🙂 ], “everywhere and nowhere is the centre, all at the same time”. Which means that yes, ‘system-as-whole’ is potentially at risk of ‘-centrism’, unless we’re aware that it isn’t. And is. And isn’t. And is. And isn’t. This can go on quite a long time… 🙂 )

First, my +1’s:

Yes! I run into this time and again. Yet I’ve not yet found a satisfactory solution. Every form of measurement is, at best, an approximation of the real world, and the gap between that approximation and the messy, complex world is where the distortion takes hold and grows. I suppose the only real answer is to define your values, set goals based on those values to chart your course, and doing the hard work of remembering the goal is only an approximation and checking in regularly on whether you need to modify the goal to remain true to the underlying value.

Right on, again. The actual financial compensation for work doesn’t matter past a certain point – except when you perceive it to be “unfair” based on the compensation of others, and your perception of the value of their work relative to your own.

****************

When I consider the above (and the bulk of your article) I worry that it all depends too much on people being very conscious too much of the time – and it just doesn’t mesh with my experience with actual people in groups. People can do amazing things – but it takes a lot to put them into motion, and they can quickly fall back into their “ordinary lives”. Periods of momentous political or social change are so remarkable remembered in history because they are so rare.

Many thanks, Jeff – the ‘+1’s much appreciated! (Nice to know I’m not considered entirely crazy… 🙁 🙂 )

“…and your perception of the value of their work relative to your own”

This is where things can get really messy in a social context, not least because of the somewhat childish ‘need’ to prop self up by putting others down, if only in a socially-relative sense such as “my work is more valuable than yours, so I’m more valuable than you”. One of the mechanisms for this is perceived social-status, often propped up by accumulation of conspicuous ‘status-objects’: possession-based economics and the relative fluidity of money as an accessible prop for social-status feed right into that ‘need’, which in turn becomes a major driver for economic problems such as wage-inflation.

“I worry that it all depends too much on people being very conscious too much of the time”

I worry about that too, a lot. Yet the catch here is that there is no way to make a possession-based economy sustainable – so we really don’t have much choice about this, because the alternative is that we’re dead. Kinda high stakes here…

What gives me hope is that most of this is really about habits – habits of thought as much as habits of action. If we look at more system-aware cultures and religions, the habits are built around consistent return to self-awareness, self-responsibility and consequences of actions and inactions. Socio-religious changes can create huge shifts in social-habits: look at the impact of 18th-century Calvinism on the Scots, for example, or 19th-century Methodism on the Welsh. In that sense, the paediarchal religion of money and self-irresponsibility that dominates the US (thank you ‘televangelists’ and Ayn Rand…) and elsewhere at present is just another dysfunctional religion, and therefore can be changed under the right social conditions. The trick is in creating the right social conditions…

What does give hope are large-scale capability-change projects such as HighScope. In that case, as little as six months of kindergarten/pre-school that quietly challenges the ‘natural’ tendency to paediarchy has lifelong impacts: for example, for those who need monetary metrics ( 🙂 ), the research shows that every dollar spent on HighScope yields at least seven dollars’ worth of return to society as a whole, in terms of personal productivity, personal capability, social stability, reduced crime and much else besides. All of that is just about challenging and changing habits, nothing more.

Sure, it helps to set up those habits early, just as it does to set up ‘healthy habits’ around eating, hygiene, risk-management, saving (in a money-based economy) and so on. And yes, in many cases and cultures this is asking for a huge change in habits. But remember that although the scale is almost unimaginably vast, this is also a long-term project: as long as we get started solidly on this at most within the next decade or two, we then perhaps have as much as a century to get the shift complete on a global scale. The hard part, really, is about finding the courage to get started. (And yeah, I do very much know, first-hand, that that’s definitely the hard part… 😐 )

One more thought about time scales – the early Christian church didn’t codify the books of the New Testament for about 350 years (or so, I’m not expert on this stuff). My understanding is, at the time of codification, it was the opinion of those involved that the long period of time was not wasted, but was the time needed for the process of God working on human scale to get things built up and discern which texts were true reflections of the divine will and which weren’t.

You possibly don’t share their opinion about divine intervention, but thinking about it yesterday I was struck about that conception of the scale of time & human change.

Also, there’s currently a lot in pop science writing about the “plasticity” of the brain. What’s not clear to me is – how deep into the brain structure does that go? It certainly doesn’t seem possible to rewire our own breathing mechanism purely through experience & willpower (probably a good thing, anyway) but are any of these deeper emotional drivers subject to learning and change, or is it only possible to build a better, more polished veneer on top of the nasty mess underneath?

John:

“You possibly don’t share their opinion about divine intervention, but thinking about it yesterday I was struck about that conception of the scale of time & human change.”

I’ll have to admit I “don’t share their opinion”, but I’d certainly agree with the point about “conception of the scale of time & human change”. We’d see the same if we look at some of the native-American cultures: it’s the Sioux, I think, who say that any major decision must consider the impacts on the next seven generations and the previous seven, which gives a similar time-span of around 300-400 years. Native Australian culture often takes a far longer time-view: one of the Aboriginal elders I talked with about this told me that, in his experience, that a specific ‘Dreaming’ is typically linked to a geologically-distinct epoch, which can well be 10,000 or more years. (He was talking there about multiple-overlays of Dreamings, straddling the pre- intra- and post-Ice-Age periods, which totalled something like 25,000 years.) That kind of view of time makes the ‘next-quarter’ focus of so many businesses look very small indeed! 🙂

On ‘plasticity’ of the brain, there’s been a vast amount of medical research on this in recent decades, particularly around recovery from stroke, brain-tumour or gunshot wounds: it’s pretty amazing just how ‘plastic’ the brain really is. In this context, though, it’s probably more about the relationships and interactions between the various sub-systems that manage action, emotion and ‘rationality’: limbic-system, ‘lizard-brain’, neocortex and so on. If we look at the long, long history of meditation and similar practices (within the Christian tradition as well as in other cultures), then yes, we can see that there definite is plasticity there, and options for, if not actually rewiring, then at least introducing distinct choice in renegotiating those intra-relationships. That’s yet another topic I need to do a blog post on Real Soon Now, I guess?