RBPEA: On empathy and gender

What is empathy? How does it differ from sympathy, and why? How do we avoid the trap of pseudo-empathy, or getting caught up in the Hunter’s Dilemma? And what part – if any – does gender play in each of these?

In line with the theme of this blog-series, in what ways can we use RBPEA – techniques from enterprise-architecture and systems-thinking, applied at the Really-Big-Picture level – to guide us to new insights on this? And how can we apply those insights back in everyday enterprise-architecture?

(A reminder about the purpose of this series. Although we’re using gender at a kind of global scale as a worked-example throughout the series, the focus here is not about gender as such. It’s much more about how to use enterprise-architecture and systems-thinking tools at very large scale and scope – Really-Big-Picture – and then bring insights and analogies from that type of assessment back down to the everyday, for practical concerns such as user-experience and service-design, or ‘classic’ EA such as application-architectures and IT-infrastructure. The ‘Practical applications’ section at the end of this post gives some guidance on that. Yes, some of the insights here about gender and the like may well seem somewhat challenging, relative to current orthodoxies: but if you find yourself getting upset about something, remember that this is primarily about practical enterprise-architectures – hence, if at all possible, bring your focus back to that.)

As an anchor back to systems-thinking, we’ll again use the SCAN crossmap of sensemaking / decision-making tactics summarised in this visual-checklist:

In recent months in the business-press and elsewhere, it seems there’s been a sudden resurgence of interest in empathy – perhaps because of its practical importance in product-design, service-design, customer-service and the like. I’d strongly agree with that concern – for example, without a strong practical grasp of empathy, I don’t think it’s possible to fully make sense of an interaction-journey across a service-boundary, or map out an ‘outside-in‘ view of a service:

But what exactly is empathy? That’s where the descriptions tend to get a bit blurry… So in the same sense as with the term-definitions for Enterprise Canvas, let’s aim here to use systems-thinking and the like to introduce a bit more clarity and rigour into the story.

Yet where does gender come into this picture? To me there are two fundamental errors or misunderstandings about the nature of empathy, that are actively promulgated on the one side by what we might call ‘women’s magazines’, and on the other by more formal feminist literature, both of which lead most people down completely the wrong path in terms of actually being able to work with empathy in real-world practice:

- mistaking sympathy for empathy

- mistaking a kind of self-centric ‘pseudo-empathy’ for real-empathy

A third error – which, again, I’ve seen often in feminist literature, though perhaps less so in ‘women’s magazines’ – is an assertion that “only women are capable of empathy”. As we’ll see later, it’s merely yet another delusory form of self-congratulatory sexism – which, as usual, just causes further unwonted confusion and doesn’t help anyone at all.

First, then, empathy is not the same as sympathy. Empathy is literally ‘outside-feeling’ or ‘external-feeling’, whereas sympathy is literally ‘same-feeling’. Sharing the same feeling with someone else is undoubtedly valuable, and a powerful means to establish context and conditions for power-with (as described in the previous post in this series). Yet it also conceals a very real danger, of which we do need to be aware, and hence not to confuse sympathy with empathy when our aim is to work with the latter.

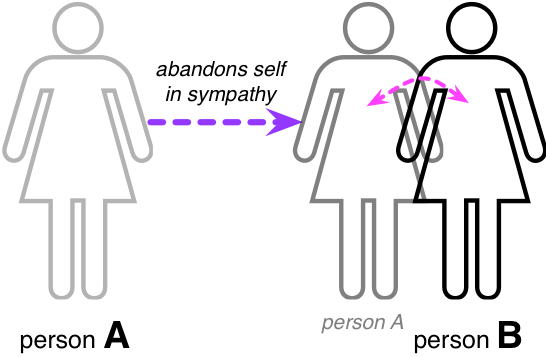

In empathy, we connect with the Other, but always maintain at least some degree of separation between Self and Other, so as to retain full choice of action. The power of sympathy is that we share exactly the same feelings as the Other: but if we’re not careful, we can get kinda ‘sucked into’ the space of the Other, and inadvertently abandon the Self. If that does happen, it can be difficult to return to the Self, or even know what the Self actually is any more. We could summarise this visually as follows:

To give a first-hand example, many years ago, as a callow arts-student living in London, I went on a vegetarian diet to ‘improve my sensitivity’ for some experiments that I was doing at the time. To some surprise, not only did it work, but it actually worked way too well: I’d get on a bus, and get ‘into sympathy’ with various people on that bus – so that by the time I got off the bus, I had this person’s hangover, that women’s hatred of her job, that man’s backache, this woman’s worry about her daughter, that woman’s still-seething-about-argument-with-mother-in-law, and this girl’s sniffling cold, all mangled together with the hyperexuberance of all those schoolkids. In short, I’d get on the bus in reasonably-sane condition, and get off it as a complete mess, solely as a result of over-sympathy: not a wise idea…!

Remember that point about power, from the previous post in this series, as ‘the ability to do work as an expression of choice‘. Sympathy can be enormously powerful in that it can give us a literally visceral experience of what it’s like to be the Other. Yet to reach true sympathy, we in effect have to let go of the Self, ‘become one with’ the Other: which means that, whilst we’re in sympathy our own choices become blurred or, worse, drowned out by the choices of the Other – and hence risk losing our own power of choice, and with it our own power as well. On the other side, there are huge dangers with attempts at sympathy being misused in ways that can be obscenely vicarious, even vampiric – intruding onto the Other’s life as a substitute for and avoidance of the work of facing the challenges of our own. (That’s pretty much the ‘women’s magazines’ obsessions with ‘the lives of the rich and famous’ in a nutshell, in fact.)

In practice, the only way that sympathy can be made to work, without a high risk of causing serious damage to someone, is to do the work to build and maintain a strong sense of Self – hence the real value of meditation-techniques, for example – and create a kind of ‘shielding’-mechanism that can be switched on at any moment, to gently break the sympathy-connection whenever there’s too much of a risk that someone’s getting swamped.

(I’ll admit I’m not that good at that skill of ‘self-shielding’. Right back to earliest childhood, I’ve been always been very thin-skinned in a ‘sympathy’-type sense – which makes me quite good at sensing out what’s going on in an overall context, but often leaves me absolutely exhausted in very little time at all. Few people seem to realise just how much work goes into maintaining even some sense of Self, and clarity of direction, whilst under the kind of full-on ‘assault of the senses’ that is all but the norm in whole-of-enterprise architecture… – and it’s especially hard to handle if one lives and works largely alone, and hence very little power-with to help speed up recovery after each session of work. If you wonder why I’m somewhat prone to bouts of withdrawal-from-everyone – and, I’d have to admit, occasional fulminations – then that point above about the necessity for thin-skinned-ness, yet the lack of ‘shielding’, might help to explain why…)

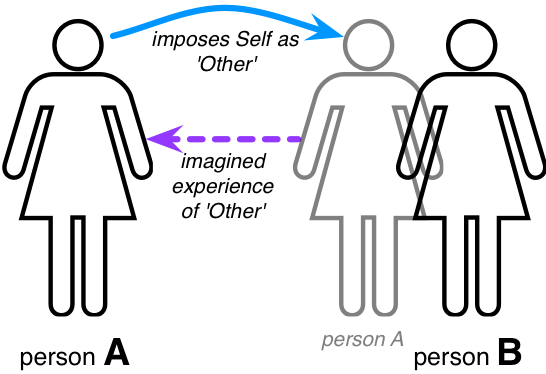

Next, empathy is not the same as ‘pseudo-empathy’. (There may be a proper technical term for this, but if there is one, I haven’t found it, so I’ll use ‘pseudo-empathy’ for now.) This is, in essence, a self-centred delusion of empathy, where the Self is imagined into the context of the Other, but where all of the assumptions and prejudices and life-experiences of the Self are imposed onto that context – often without any actual connection to or with the Other at all. A short-hand way of putting this is that it’s about “how I believe I would feel in that context”, rather than “how the Other actually feels in that context” – but often deluding oneself that Self and the Other are essentially the same. We could summarise this visually as follows:

I’m going to be blunt here: my own experience, throughout almost five decades of reading about ‘women’s experience’, and working with feminists or self-styled ‘pro-feminists’, has been that whenever the term ’empathy’ is mentioned by such people – particularly in any Western culture – it almost invariably turns out to be some form of pseudo-empathy. Too often it is, bluntly, little more than a vain, arrogant, unthinking insult: try reading, for example, the understandably-furious response of many feminists in non-Western societies – India, Africa, Muslim cultures – to assertions by Western feminists that the former’s explicit, conscious choices as women are somehow evidence of ‘patriarchal oppression’, and that they therefore need the Westerners to tell them what to do.

(As one Indian colleague put it, she regards it as yet another form of ‘white colonialism’, the arrogant, self-important, patronising (matronising?) missionaries of yet another foreign cult – with no interest in her as herself at all, other than as potential fodder for the foreigners’ own petty feuds. Not surprising that she’s not interested in playing along with the game…)

In gender terms, there’s also often a less-than-subtle assertion that men don’t even have feelings, or at the very least that any such feelings that men might have are inherently irrelevant by comparison with those of women. This too leads, all too often, to some frankly sickening displays of misplaced pseudo-empathy. The following is an approximate quote from memory of a father’s tale that I read in the BMJ (British Medical Journal) a few years back:

I had been present at his birth, I was at his side throughout his illness, so it seemed appropriate, last Christmas, that I should be the one to carry our son’s small coffin to his grave. … A week a or two later, one of the women patients at our general-practice surgery asked me how my wife was feeling. “How dreadful it must be for her!” she said, “How awful! No man could possibly know how painful it is for a mother to lose her child!” She burst into tears: and I found myself in the invidious position where I, as the bereaved parent, was forced to comfort someone who had merely imagined her way into loss…

Behind its grandiosity and self-importance, pseudo-empathy is actually a form of abuse – yet one that’s so pervasive now that few people seem able even to recognise it as abuse. I’ll allow myself to indulge briefly in gender-stereotypes here – though only because it’s the same gender-stereotypes that underpin the delusion that ‘only women are capable of empathy’ – and point out that it’s a kind of ‘subject-based’ abuse that girls and women in particular tend to inflict on others. (By contrast, men and boys tend to inflict ‘object-based’ abuse on others – a comparison we’ll come back to when we look at abuse and gender in a later post in this series.)

In subject-based abuse, the Other is not acknowledged as having any independent life at all, but as a subordinate extension of Self that exists solely to serve the Self. (It’s a typical and natural aspect of the two-year-old’s view of the world, and part of what drives the infamous ‘terrible twos’ – but the whole aim is that one should grow beyond that self-centredness within a year or two…) In SCAN terms, it’s a crushingly-Simple view of the world – that one’s own opinions and beliefs are The Truth™, that those who seem ‘the same’ must necessarily have exactly the same experience of the world as one’s own, and that the Self has an absolute ‘right’ to punish and silence those who dare to say or act or show that they are or believe or experience anything different from that. Comforting fantasy though it may be, it’s not a wise approach for any adult to apply to the real complexities of the real world – that point should be all but self-evident, I’d hope? And yet, unfortunately, it is a very, very common delusion: hence vast trails of ego-driven destruction throughout almost every possible context – and perhaps few more so than in (again, let’s be blunt about this?) almost anything touched by present-day ‘feminism’. Oops…

To get beyond that kind of childish mess, it’s essential to do a Reframe, a transition from pseudo-empathy to true empathy. To me, one of the key distinctions between mere female perpetrators of ‘kiddies-anarchy’, versus real feminists, is that they can make this shift. There’s a great example of this in an interview [PDF] with feminist filmmaker Melissa Llewelyn-Davies, about her documentaries with Masai women in Kenya:

…at the beginning one has the feeling that women don’t have any power, they have no rights in cattle, they’re actually powerless; but as the film evolves we begin to see that it’s much more complicated and at many critical moments women assert themselves in a quite remarkable way.

Yes, exactly: the real world is surprisingly complex, Ambiguous, Not-known; and real people do indeed do things that we don’t expect, and generally work out their own ways of doing things that can be very different – and better – than our own. And shallow Simplistic notions of ‘patriarchal oppression’ and suchlike – especially those based on little more than random, rampant, ridiculously-narcissistic Other-blame – really don’t help, at all, in finding workable ways through those many minefields of human complexity… But I digress…

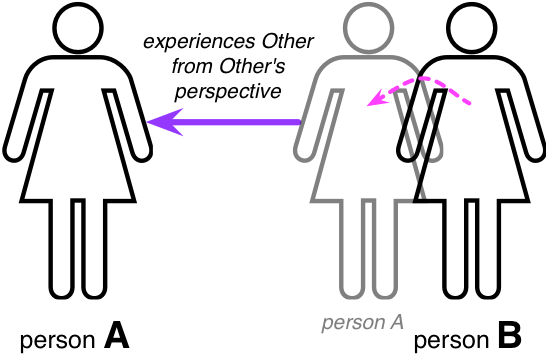

True empathy is about seeing the world from the Other’s perspective, whilst still being the Self. Unlike with pseudo-empathy, we explicitly guard against imposing our own assumptions on our felt-experience of the Other’s world; and unlike with sympathy, we take care to not merge with the Other – otherwise, again, we’d risk inappropriately distorting our view of that world, and possibly the Other’s view of their world as well. (Questions about whether, when and under what circumstances normative-enquiry – in other words, intentionally changing the Other’s world, whether they wish it or not – is ever appropriate, is something I’ll gently sidestep for now: that addendum about ‘whether they wish it or not’ does, in itself, kinda imply that it’s more likely than not to act as a form of abuse, though.) We could summarise true-empathy visually as follows:

There’s a powerful first-hand description of this in a post on LinkedIn by John Walters, ‘What I Discovered About Empathy In A Combat Hospital‘, about an experience whilst serving as a soldier with the American forces in Afghanistan. A young Afghani had thrown a grenade at their command-post, and had been shot in the stomach in return; Walters then has the task of guarding him in hospital for treatment and recovery prior to trial in court:

I was angry that he tried to kill my fellow Marine and I was angry that I had to abandon my team for three weeks while he received a few operations and recovered enough to be handed over to the local police. [Yet] when you’re staring at a guy 24/7 for three weeks you have a lot of time to think. … My anger toward the young man on the hospital bed turned into curiosity as I started to wonder why he would approach a guarded outpost on camelback and throw a grenade. He couldn’t possibly have thought he would get away with it.

In the three weeks I spent guarding the detainee at the hospital I, for the first time since I had been in his country, began to see his world. I began to think how the two of us, perhaps, weren’t that different. He was not an extremist militant. His only interaction with the Taliban prior to us being there was most likely when they paid him for his opium harvest. His was a simple life without electricity, running water, or proper schools. He knew nothing of 9/11. In fact, he had barely heard of Americans; most of the people in his remote village thought we were Russians when we first rolled into their town. He was doing what he thought was right for his village when he engaged my fellow Marine. By the end of his hospital stay I had come to empathize with him.

In empathy, the connection with the Other is kind of like a one-way (inbound-towards-the-Self) version of sympathy: we need to reach out to sense and build an understanding of the Other’s world, yet without actually intruding on their space. It takes practice, and a lot of careful, respectful ‘listening’ in one form or another, but it’s actually not all that hard to do. It’s the other side of it, though – checking and holding back on our own assumptions and expectations, to avoid a lapse into the self-centredness of pseudo-empathy – that’s often really hard. For a classic illustration, take a look at late-19th-century views of ‘The Future’, showing, for example, ‘air-bicycles’ held up by steam-engine-powered balloons, and ridden by prim-and-proper gentleman in spats and bowler-hats, and ladies in bonnets and crinolines: yes, it’s laughable now, but actually no more laughable than some of our own present-day attempts at empathy…

We can also see the crucial distinctions between sympathy, pseudo-empathy and real-empathy in John Boyd’s OODA-loop – or, more specifically, in the ‘Orient’ phase of that recursive/re-entrant ‘Observe / Orient / Decide / Act’ cycle:

If we fall solely into sympathy with the Other within the Orient phase, we might be able to fully experience the Other’s world – yet so much so that we’d quite probably forget why we came there. If we lapse into pseudo-empathy, we’d find ourselves making decisions based on little more than arbitrary assumptions about the Other’s world. Neither of those could be described as useful tactics to apply in the context for which OODA was originally developed, namely split-second combat in supersonic fighter-jets… What does work there is true-empathy: allowing ourselves to become fully aware of the Other’s world, and the bases for their sensemaking and decision-making, whilst still retaining full awareness of our own – and our own purpose and intent within that context.

Which brings us to an interesting point. In general I’d recommend to avoid gender-stereotypes, but again this one is a follow-up to that earlier ‘feminist’ assertion that “only women are capable of empathy”. If we look at this whole domain once more, but now in terms of gender-stereotypes, then it’d be sympathy – rather than empathy – that would more naturally fit ‘feminine’ stereotypes such as the Carer. Likewise, unfortunately, the dysfunctions of pseudo-empathy are all too ‘feminine’, as we’ve seen above. Yet real-empathy, as we can see from that description of the OODA-loop above, would fit more naturally not to a ‘feminine’ stereotype, but to a ‘masculine‘ one – the Warrior or the Hunter. This is perhaps best illustrated by a well-known quote from Orson Scott Card’s sci-fi novel ‘Ender’s Game‘:

“In the moment when I truly understand my enemy, understand him well enough to defeat him, then in that very moment I also love him. I think it’s impossible to really understand somebody, what they want, what they believe, and not love them the way they love themselves.

…but then follows on into a far bleaker side of empathy, that we might describe as the Hunter’s Dilemma:

And then, in that very moment when I love them… I destroy them.”

That, perhaps, is right out at the extreme end of what true empathy may demand from us: that to survive, or to protect or feed our family, we must be prepared to connect with and yet to kill something or someone that, in that moment, we literally love more deeply than we love ourselves, more deeply than anything else in the world. Think for a while about what that really means; what challenges that would place upon you and your sense of self; on how you relate with others, on how you relate with yourself. Kind of explains the presence of animal-totems and suchlike in so many ‘primitive’ cultures; and how the lack of such deep-empathy in our own cultures might also explain some of that gnawing emptiness that pervades through so much of our so-called ‘civilised’ world, too.

If you thought that empathy was easy, or easily-gendered, think again…

Practical applications

(Remember that this is where we bring it down from the big-picture level, and put the insights from above into practice in the everyday. Gender and suchlike themes may perhaps have little to no direct connection with what we’re likely to be working on in routine enterprise-architecture practice, but the insights almost certainly will have real applications here. See and use the underlying principles identified above: but don’t get too hung up on any of the ‘gender’-type details from back there.)

First, sympathy is fundamental to the operation of any enterprise: it’s what links people together in common cause. Machines may not have feelings, but people certainly do: and designing for that fact – rather than pretending it doesn’t exist – is generally a wise way to go. The trick (or whatever else we’d better call it) is that sympathy needs to be created as an expression of personal choice, in each person – otherwise disempowerment and disengagement is the inevitable outcome, especially over the longer-term. I won’t describe any of the ‘how-to’ for that – there’s a vast literature on it. The catch, of course, is that a sizeable amount of that literature would best be politely described as ‘not very useful’: but from the definitions and examples above, you should have some means to be able to find the genuinely-useful gems amongst the dross.

In a business context or other social context, in some ways there’s actually less of a danger from under-sympathy than there is from over-sympathy – otherwise known as ‘groupthink’. In a sense, groupthink is usually a muddled mix of excessive-sympathy – everyone busy agreeing with everyone else – that’s ultimately founded on pseudo-empathy – some one person’s preconceptions and assumptions about ‘how the world really is’. (We’ll even see the same happening sometimes in a purely technical space, such as in ‘race’-conditions where similar systems get stuck in a reinforcing-feedback loop: one hugely-expensive example was the bidding/sell-spiral across a cluster of automated trading-systems that was the prime cause of the 1989 Stockmarket-crash.) Because of this, it’s often really important to deliberately build a certain amount of discord or non-identicality into a system: a good example came up in the previous post, about how mission-critical contexts often use multiple systems, developed by different design-teams, to act as cross-checks on each other’s decisions and operations.

Delusional structures built on pseudo-empathy are a disaster-area-waiting-to-happen, wherever they occur in an architecture. For example, to be blunt, the management-hierarchies of most large organisations are little more than pseudo-empathy run rampant.

(And yes, I’m well aware that many of those managers are male – I did say that that point about gendering of pseudo-empathy was a stereotype, didn’t I, not a purported ‘fact’? Beyond the stereotypes, the only certain fact out there is that ‘kiddies-anarchy’ is a lot more of an ‘equal-opportunity employer’ than any of us would like… It’s also that in part the Taylorist/MBA model of organisation actually requires dysfunctionality at a systemic level, in order to prop its delusions of ‘control’: we’ll see more on that in a later post in this series, on abuse.)

Another point to watch for is that many IT-systems in effect tend to drive the whole enterprise-structure towards pseudo-empathy, because of an implicit design-effect that I describe as ‘cutting off the crusts’. The real-world is messy, uncertain, always with a high degree of often-quite-subtle uniqueness; yet most conventional IT-systems depend on mass-sameness, typically imposed through predefined data-schemas and the like. As with any other ecosystem, often the most crucial information arises right out at the edges – the ‘crusty bits’. But as information moves ‘upward’ through a management-hierarchy – especially in a larger organisation – more and more of the ‘crusts’ are cut off, because they don’t fit the predefined schemas, causing the loss of the information that matters most. By the time information reaches the ‘top’ of the hierarchy, it’s often been so smoothed-out and sanitised that pseudo-empathy – in the form of a misplaced excess of certainty about ‘how things really are’ – is rendered almost inevitable. Not helpful…

The need for real-empathy in areas such as product-design is illustrated well in this quote from Ben Thompson, in John Kirk’s ‘Apple’s Design: The Gift That Keeps Giving (2 of 2)‘:

The most fundamental part of design is truly understanding your customers at a deeper level than they even understand themselves.

…and another, from John Kirk himself, in the same post:

The only way to make a product that your customer understands from the start is to understand your customer before you start to make the product.

Yet it’s not just in product-design that this matters: it’s relevant and important everywhere that different opinions and experiences exist. Which is just about everywhere within an enterprise-architecture, in fact. Tools and techniques such as Customer Journey Mapping are absolutely essential as a way to build skills, experience and competence in real-empathy within an enterprise-context.

There’s plenty more that could be said on this, but probably best to stop here for now. In the next post in this series, we’ll move on to the contentious topic of equality, and see what insights a gender-lens at the RBPEA scale can provide that we can likewise put into practice down in everyday enterprise-architecture.

I think that using enterprise architecture techniques outside of the common domains for enterprise architecture is a great idea. It is as you say, a great test for the techniques to see if they apply.

In regards to this discussion, I think you have to be really careful about how you define empathy and sympathy. I don’t agree with your definitions. Empathy is defined and researched very thoroughly in psychology and counselling work. Carl Rogers worked a lot on empathy as part of his person-centered counselling approach. He defines empathy as:

“[the perception of] the internal frame of reference of another with accuracy and with the emotional components and meanings which pertain thereto as if one were the person, but without ever losing the ‘as if’ condition.”

This is similar to your definition. But the crucial component is to understand the emotional components and almost (and sometimes actually) feeling the emotions of the person you’re empathising with.

I can’t find a quote for the definition of sympathy. But in counselling literature it is a much more superficial practice. It is being compassionate, but fleetingly so. It’s making statements like: “I’m sorry for your loss” or “that must be so difficult for you”.

There is a parable to describe the two in counselling literature.

“Imagine being at the bottom of a deep, dark hole. Peer up to the top of the hole and you might see some of your friends and family waiting for you, offering words of support and encouragement. This is sympathy; they want to help you out of the pit you have found yourself in. This can assist, but not as much as the person who is standing beside you; the person who is in that hole with you and can see the world from your perspective; this is empathy.”

So to keep it about practice of EA techniques to a broader domain and not about the domain itself in this case empathy and sympathy, my point is that it’s very important that generally-accepted definitions be derived from the domain or field of study. Of course as you’ve highlighted before, it’s important to use critical thinking to call out any term hijacking.

Hi Anthony – and thanks.

On definitions, as you’ll have seen from other contexts, I rarely find ‘official’ definitions much use – perhaps especially so in enterprise-architecture. What I tend to do instead – as you’ll have again seen elsewhere – is go to a combination of ‘literal-meanings’ (the respective meanings of the root-components of a word, if any) and direct-observation of what’s actually going on in the context. For the root-components, ‘sympathy’ is straight Greek ‘sym-‘ = ‘the same’, ‘-pathy” = ‘feeling’, so it’s literally ‘the same feeling’ – so I look for something where ‘the same feeling’ is shared. (That’s also the same meaning as used in physics, when we talk about two pendulums being in ‘sympathetic vibration’ with each other.) ‘Empathy’ is trickier, and appears to be a much more recent (18th-century?) Latin/Greek mangling, with ’em-‘ as one of the standard derivatives of Latin ‘ex-‘, ‘outward’, hence a literal-meaning of ’empathy’ as ‘out-feeling’ – which, in an individual sense would imply ‘outward expression of feeling’ (a term/meaning which doesn’t seem to exist?), but in a power-with/exploratory sense, as here, gives us the sense of reaching in to bring out and/or experience the feelings of the Other, which is, as you say, pretty much the ‘official’ definition of empathy, and the one we’d use in, say, customer-journey mapping.

Given those ‘natural-meaning’ usages above, what it kinda suggests quite strongly is that the ‘official’ definition of ‘sympathy’ is perhaps more than a bit misleading. There’s a very small element of a literal ‘sym-pathy’, ‘same-feeling’, in that we build a bridge for power-with (and also permission for empathy-type exploration) by expressing that we too have had the same feeling in the past – though there’s actually a real danger if the ‘sympathetic person’ does get stuck in literal sympathy, because then there’s then no way for either party to get out of whatever ‘downer-state’ the Other is in. Instead, in terms of natural-meaning, a more accurate description of what’s happening in that ‘official’ definition of sympathy is more a combination of a small amount of sympathy, getting close to the Other but with the Self’s ‘shields’ flicking up and down (though mostly up), as a means to establish ‘disengaged’-yet-supportive empathy – exactly as in your quote above of “is in that hole with you and can see the world from your perspective; this is empathy”, though in some ways with less personal-commitment than in the full parallel-empathy of “standing beside you in the hole”. In fact, much of what you’ve described above as ‘sympathy’ would more accurately be described as ‘pseudo-sympathy’, in the exact same sense as ‘pseudo-empathy’ in the article above: a Self-focussed simulation of sympathy that has no real connection with the Other at all – hence why it should indeed be described as “a more superficial practice”.

On a personal note, I’d have to say I’m really pleased to see this critique from you. 🙂 Three years ago, you were the almost-timid self-described ‘newbie’ who asked me to write some notes for you, that became the post ‘What I do and how I do it‘, on which this series on the practice of RBPEA is largely based. And yet here you are, just three years later, coming back at me with a well-thought-through critique, rightly claiming your ‘right’ to do so as a direct professional-peer. That’s a huge change in perspective and professional-confidence – a great illustration of just how far and fast you’ve come, in terms of skill and experience and the rest, over what is really a very short time. I hope it’s not seen as arrogant or patronising of me to say this, but I really do want to say “Well done!” 🙂

Anthony – one other note on your “But the crucial component is to understand the emotional components and almost (and sometimes actually) feeling the emotions of the person you’re empathising with.”

That is how it’s described in the text above, though evidently I haven’t described it well enough: my apologies… That linkage is also explicitly shown in the diagram, as the dotted one-way lilac-coloured arrow from Person-B to the shadow of Person-A. Crucially, unlike in sympathy, it’s only a one-way arrow, a one-way flow of connection: since the whole point of the exercise is to find out what the Other’s experience really is, Person-A needs to take care to not intrude on the Other’s (Person-B’s) space or experience.

That point about “taking care not to intrude on the Other’s space” is actually the difference between explorative versus normative. In explorative-enquiry, we aim to explore the Other’s experience in their own terms, whereas in normative-enquiry – of which religious-missionaries are perhaps the prime example – the aim is to enquire of the Other’s experience so as to ‘correct’ it ‘for their own good’ and other suchlike excuses. There are, on occasion, good reasons for normative-enquiry, but the ethics of it are enormously complex, and in far too many cases it ultimately turns out to be yet another form of structurally-imposed violence and/or abuse. Oh well. 😐

Thank you Tom for your response and in particular the personal note. I’m always thankful of the teachers I have had to get where I am now, whether they be in person or virtual.