RBPEA: On equality and gender

What is equality? How do we create it, support it? – and why? Is equal always the same as identical? – and if not, why not, and how not? And what part does gender play in any of these? – if it should play any part at all?

In line with the theme of this blog-series, in what ways can we use RBPEA – techniques from enterprise-architecture and systems-thinking, applied at the Really-Big-Picture level – to guide us to new insights on this? And how can we apply those insights back in everyday enterprise-architecture?

(A reminder about the purpose of this series. Although – as explained in the intro-post to this series – we’re using gender at a kind of global scale as a worked-example throughout the series, the focus here is not about gender as such. It’s much more about the principles and practice of how to use enterprise-architecture and systems-thinking tools in general at very large scale and scope – Really-Big-Picture – and then bring insights and analogies from that type of assessment back down to the everyday, in practical enterprise-architectures.)

Since painful experience shows that a lot of people tend to get lost at this point – even before we’ve properly gotten started on any exploration – let’s start off with what I’d believe is an always-appropriate anchor-principle or reference-touchstone for any explorations of equality and gender:

The needs, concerns, feelings and fears of women and of men are of exactly equal value and importance.

If ever you’re in doubt during this exploration, please do refer back to that anchor-principle – because that is the anchor I’m referencing and building upon in all of what follows.

(If you’re unhappy with that assertion above – if instead you want to insist that the needs, concerns, feelings or fears of just one gender must have priority over others, solely on the basis of gender, it’s probably best to stop reading now, because what follows on logically from that assertion above will only annoy you. I would gently point out, though, that if you do insist that one gender should always have such priority, such a position is by definition both prejudiced and sexist. Just so you know…)

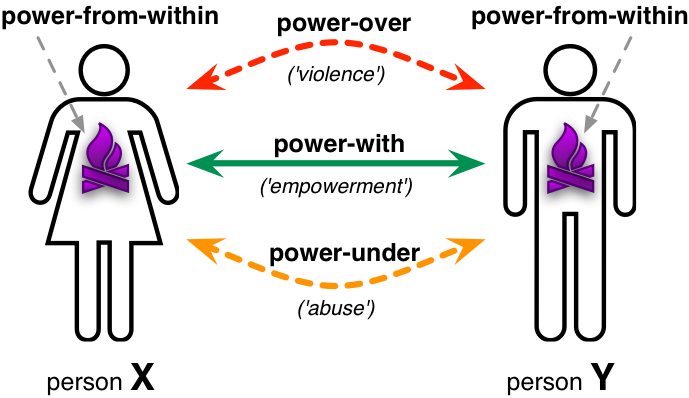

Another anchor I’ll reference here is the power-model that we explored in the first main post of this series, on power and gender, that again views the sexes as exact equals:

(By the way, although it’s still usual to describe gender in terms of a simple binary distinction of male-or-female – and I’ll mostly do so here, for practical reasons – in reality it’s a lot more complex than that, with reproductive-anatomy, brain-type (much-denser corpus-callosum cross-connect in ‘female’ type), sexual-orientation and other factors all set at different periods in gestation, and with also less-common variations such as intersexuals (‘hermaphrodites’), asexuals, XXY / XYY chromosome-types and others. And that’s before we include into the picture all of the post-partum concerns such as transsexuals and the like, or socialisation of gender. In short, as with many other aspects of architectures, it might seem Simple at first, but it’s actually a hugely-complex ‘It depends…’. Other cultures are often more realistic about this – for example, I remember reading once that one of the native-American cultures identifies at least sixteen distinct sexes – but at the very least we should be aware that the standard Western-style binary notion of exactly-and-always-only two sexes is often dangerously over-Simplistic.)

We may also need to refer back to the crucial distinctions between empathy and sympathy, and the real dangers of ‘pseudo-empathy’, that we explored in the post on empathy and gender.

As in the other posts in this series, we’ll again use the SCAN crossmap of sensemaking / decision-making tactics, to anchor the discussions back into systems-thinking. In SCAN terms, the obvious focus for equality is around Reciprocation and Resonance, though all the other SCAN tactics may also apply, as summarised in the visual-checklist below:

So where do we start? One option would be to start at a literal place, in this case the cafe opposite the Eurostar ‘Arrivals’ exit, at St Pancras station in London. I have a couple hours to wait before my colleague’s delayed mainline train gets in, so I settle down to the usual people-watching. As it happens, that cafe is right next to the broad passage that leads to the station’s main toilets – and whenever it’s just before or just after one of the Eurostar trains is due, it definitely gets kinda busy there. The men’s toilets, there’s a lot of people going in and out, but there’s never a queue as such. Yet the women’s toilets? – at those times there’s always a long queue, sometimes right onto the main concourse…

But why? Why does this happen so often around the women’s toilets, in theatres, at festivals, at just about any event?

The short answer is that some designer or planner has failed to understand that ‘identical’ is not always the same as ‘equal’. It’s actually a classic architectural mistake – almost certainly as a result of failing to engage appropriate empathy – resulting in an assumption that provision of the same physical space will satisfy everyone’s needs. Yet to satisfy needs, we must first start from outcomes. I won’t go into the detail behind the calculations, but if we do start from outcomes, we discover that to get the same throughput – serving the same respective needs, the same number of women and men through the respective facilities in the same amount of time – the space allocated for women’s-toilets would need to be between three and five times larger than that allocated to the men’s. It’s a real and, too often, literally-painful example of where ‘identical’ turns out to be very far from ‘equal’.

However, my suggestion would always be to start from a base-principle of assumed-identicality, and then – as with any other form of architecture – explore any reasons why (as in that case above) the principle of identicality should not hold. In effect, we manage variance (non-identicality) in the same way as for any other architectural-waiver: it’s perfectly okay that variances from identicality may well be needed in certain contexts, but we need to explain the reasons why we’re proposing such non-identicality – and be able to justify each variance, too. We also need to flag any variance as subject to future review – again, exactly as per any other architectural-waiver.

But it’s interesting – and worrying – to see just how much that principle is not being applied in most current approaches to gender-equality…

Yet where do we start on that? One useful place, I’d suppose, would be perhaps my favourite quote from Germaine Greer. This is from a very early interview – maybe the late 1960s, I think – in which she’s asked to define what she means by the term ‘feminism’:

[Feminism is] about exploring all the possibilities of being fully human, in a woman’s body, and from a woman’s perspective.

I like that answer a lot, not least because it includes that crucial balance between nature – “in a woman’s body” – and nurture – “from a woman’s perspective”. (Others would describe the same dichotomy in terms of sex and gender respectively.) I’m less happy that there’s a key word missing from the definition, but we’ll come back to that later.

The catch is that that definition of Greer’s above is inherently sexist, in a literal if non-pejorative sense: it defines and views a person solely in terms or sex or gender, and implicitly excludes all of those who do not match to that particular filter on the world. And I’d have to say that I’m long way from happy about that: I much prefer to start from people as people, as themselves first, rather than in terms of some arbitrary predefined set of labels. The huge danger with predefined filters – as we know all too well in enterprise-architecture with concerns such as IT-centrism and the like – is that they too frequently end up creating ‘term-hijacks’ that block out much of our view of the whole, making it all but impossible to work on the whole as whole: and that’s not a good idea, as we again know all too well as enterprise-architects.

These days I wouldn’t describe myself as a feminist or ‘pro-feminist’, though I probably would have done so in the past. To me now, that kind of gendered label is just too narrow, too arbitrary. Instead, I’d identify myself more as an anarchist, a humanist, a peopleist, a no-label-comes-first-ist: people as people, people as who they are, in all of their complexities and subtleties. In that sense, and as an assertion about everyone as true equals to each other, I’d rework Greer’s definition as follows:

It’s about each person exploring all the possibilities of being fully human, each in their own body, each from their own perspective.

And that emphasis on the individual first, rather than some arbitrary filter such as sex or gender or whatever, is really important. Other than some relatively-minor anatomical differences – the infamous ‘spare rib’ and so on – there’s only one fundamental difference between men and women: that (most) women can bear children, and men cannot. That’s it. Everything else is differences in emphasis or tendencies only, where the difference within the sexes are greater than the differences between them. (This even extends to breastfeeding, by the way: even in men the basic equipment is there, so to speak, and in extremis some men have been known to do so.)

The crucial word that’s missing from Greer’s definition is responsibilities. Without it, it either risks or implies self-infantilisation – rejection of personal power, a self-imposed ‘inability to do work’ – and/or a demand or assertion that only the Other has responsibility – otherwise known as structural-abuse, using social-structures to “offload responsibility onto the Other without their engagement and consent”. As we saw in the post on power and gender, each of those is not a good idea; and combined, definitely not a good idea… Hence we really ought to add that point about responsibility to that ‘humanist’ version of Greer’s definition, as follows:

It’s about each person exploring all the possibilities and responsibilities of being fully human, each in their own body, each from their own perspective.

I’m always wary of any kind of ‘-ism’, such as feminism, nationalism, ethnicism, or whatever the self-selected ‘in-group’ might be – because over time they always morph into ‘me-first-ism’. They might start out with an assertion of “All xxyy are equal” or suchlike: but sooner rather than later, that addendum of “but <the in-group> are more equal than others” pops up on the scene – and we all know exactly where that leads, and, worse, where it ultimately ends up. And I’m not okay with that. I never have been. That’s actually a key part of whom I am, that I’m not okay with that kind of injustice.

In terms of gender-equality, I wasn’t okay with it when things were – and in places still are – unequal or unfair towards women; and I’m also not okay with it now when things are – and, it seems, increasingly every day – unequal and unfair towards men. Sexism is sexism, whoever the abused-Other may be: and whichever way it’s played, it’s not okay. The only thing that is okay – that would be okay, if it ever existed – would be a genuine, respectful, gender-equality: yet the sad tragedy is that, in Western cultures especially, right now we’re possibly further away from that than we ever have been – though not in the way that most people seem to think…

So, using a systems-thinking lens around Reciprocation, let’s look at a few themes that, logically, should be equal, but as we’ll see, most definitely are not. First, let’s restate that anchor-principle:

The needs, concerns, feelings and fears of women and of men are of exactly equal value and importance.

And let’s first note some examples of language:

— The term feminist has several reasonable and commonly-used definitions: the version we’ve used above is about “exploring all the possibilities [and responsibilities] of being fully human, in a woman’s body and from a woman’s perspective”. Its logical counterpart, masculist, should therefore be about “exploring all the possibilities and responsibilities and being fully human, in a man’s body and from a man’s perspective”. But that latter kind of definition just doesn’t exist: instead, the only definition of ‘masculist’ that I’ve ever seen is “man trying to prevent a woman being a feminist” – in other words, a negative-definition in which the needs and concerns of the woman are the only thing considered valid or important.

— Support for women’s rights is frequently regarded as one of the highest social priorities of all in self-styled ‘civilised cultures – so much so that Australia, for example, very nearly had a Bill Of Women’s Rights before it had a generic Bill Of Rights. (In essence, that Bill Of Women’s Rights would have mandated that all law be reframed such that women alone had ‘rights’, and men alone had blame.) The logical counterpart, men’s rights, is frequently dismissed as a laughable or even dangerous bad-joke. (Which it is, of course, but so are ‘women’s rights’ and all other purported ‘rights’ – see the post ‘Four principles – 2: There are no rights‘). Again, only women’s needs and concerns are considered important here.

— The term misogyny literally means ‘dislike of women’, but in most of its many, many usages it seems to be classed as one step short of a capital crime. Its logical counterpart, misandry, or ‘dislike of men’, seems to be very rarely used, even though almost all feminist theory and literature is full of it. Another example where only women’s feelings are considered important.

— The term gynophobia literally means ‘fear of women’. It’s perhaps less-used than ‘misogyny’, but again is an epithet that seems supposedly to imply utterly-unacceptable if not near-criminal behaviour – even though it is literally a fear, and hence not actually under the respective person’s direct choice or control. Its logical counterpart, androphobia, ‘fear of men’, is another term very rarely used – and when it is, it seems to be regarded as a natural response to ‘the patriarchy’ or whatever, therefore justifying and exculpating any assaults against men. Yet another example where the feelings of women are accorded absolute priority, whereas men’s fears are denigrated and dismissed.

— The terms erotica and pornography relate to two types of materials with essentially the same intent, namely to raise and maintain sexual arousal. Although there’s a risk that it can become addictive – for example, apparently 10% of American women read twenty or more Mills & Boon / Harlequin ‘romance-novels’ per month – it does seem that many people, both women and men, do need this to maintain overall health. The key difference between the two terms is that the term ‘erotica’ is applied to primarily textual materials, and is frequently described as ‘good’, whereas ‘pornography’ is applied to primarily visual materials, and is frequently derided as ‘bad’. Here, however, we hit up against a gender-stereotype with a real physiological background, in that testosterone shifts the sexual drive from ‘Who’, or textual, more towards ‘What’, or visual: in her book ‘The Change‘ Germaine Greer described this as her first-hand, in-person experience as a direct impact of testosterone-therapy during menopause. Which, if ‘erotica’ is arbitrarily described as ‘good’, and ‘pornography’ is arbitrarily described as ‘bad’ – even if in essence they have exactly the same role – then support for women’s sexuality is therefore being arbitrarily defined as ‘good’, whereas support for men’s sexuality is being arbitrarily defined as ‘bad’ in itself. Once again, women’s ‘needs and concerns’ are supported, whilst men’s are derided and denigrated, or used as ‘justification’ for yet further Other-blame against men.

— The terms matriarchy and patriarchy literally mean ‘rule by the mothers’ or ‘rule by the fathers’ respectively. In reality, it’s probable that neither form of government actually exists, or maybe ever has existed: for example, as we saw in that interview with film-maker Melissa Llewelyn-Davies, in the previous post ‘RBPEA: On empathy and gender‘, even in the most supposedly male-dominant cultures, the women can always find a way to get what they want. Yet whilst matriarchy is often presented as a more-than-desirable aim, the’ natural order of things’, the term ‘patriarchy’ is used more as a general-purpose synonym for ‘bad’, ‘everything wrong in the world – and it’s all men’s fault’. (A perhaps extreme example is Monica Sjöö‘s New Age and Armageddon, in which the word ‘patriarchy’ or ‘patriarchal’ is used literally more than a thousand times, invariably for the purpose either of Other-blame, self-justification for Other-abuse, or both.) Again, usages of language in which women’s needs, concerns, feelings and fears are accorded the highest priority, whilst men are merely blamed.

In short, all of this is a very, very long way from any honest form of equality…

Yet how does this also work out in real-world practice at present? Here are some examples:

— Focus of charities – this one’s from the Oxfam store in town:

Empowerment, it seems, is reserved for women only. Men need not apply – regardless of their needs.

— High-school education – such as in this current campaign to encourage girls to take up maths and physics:

Science careers ‘are not the preserve of men‘, says the UK’s Education Minister Nicky Morgan, in launching this ‘Your Life’ campaign. (From an enterprise-architects’ perspective, her assertion, in the text of the speech, that the notion that arts and humanities skills have real business-value “couldn’t be further from the truth” is, uh, interesting, given that there’s an increasing if belated awareness of just how important these skills are in product- or service-design, software-development and much, much more.) Yet we might note that there’s no matching campaign to encourage boys to take up humanities; no matching assertion, for example, that “Nursing and childcare are not the preserve of women” – even though there’s a very real need for more men in both. And the language itself – “not the preserve of” – is oddly combative, oddly aggressive… why?

(And for that matter, whatever happened to women’s choices? I’m thinking immediately of a colleague at a research-lab, who went into the sciences because she was told at school that ‘that’s what women should do’, but slowly realised that what she really wanted to do was ‘something to do with people’. In a very literal sense, her own needs and choices had been ignored and overridden, solely to satisfy someone-else’s arbitrary gender-quota…)

— In university education: A few decades ago, there were significantly fewer women than men at university. Huge efforts were placed to bring the numbers more into balance, with all manner of ‘minority group’ support for women students. These days, though, it’s very much the other way round, as summarised in a Guardian article, ‘The gender gap at universities: where are all the men?‘:

“In 2010-11, there were more female (55%) than male fulltime undergraduates (45%) enrolled at university – a trend which shows no sign of shrinking.”

“It’s unclear why certain subjects attract more women than men (or vice versa), says Claire Callender, professor of higher education studies at the Institute of Education. “It’s largely associated with what happens in schools. One of the key predictors of what someone will study is what they did at A-level. There have been lots of attempts to encourage girls to study STEM subjects.”

Fewer programmes have focused on getting more men into higher education. Educationalists say the underrepresentation of male university students is down to attainment patterns in schools: girls outperform boys and are more likely to stay on at sixth form.”

As we can see with the ‘Your Life’ project above, there are still plenty of programmes to increase numbers of women in university; almost nothing at all for men. And, yes, despite women being in the majority, most of those ‘minority support’ facilities for women are very much in evidence. And, we might note, no questions about why “girls outperform boys” at school – although the inverse was considered a major concern two or three decades ago.

My local university, Essex University has a student-ratio of 5060 female, 4395 male, so you might think that the headline article on its website – ‘Time to tackle the gender gap‘ – might perhaps describe something about how they’re tackling that imbalance. Actually, no: it’s solely about “the underrepresentation of women in senior [academic] roles”.

In other words, inequalities against young men, constructed and maintained at a structural level – yet seemingly those men and boys alone are blamed for their ‘failure’.

— The oft-quoted assertion that ‘men earn more than women’: yes, it does exist in some areas. However, it’s a lot more complex than simplistic notions of gender alone: to understand what’s actually going on in that context, we need to include personal career-choices, parenting-gaps (whose impacts are less about gender as such, than about the insanities of our culture’s ‘economics’), risk-profiles (of the ten most high-risk/high-unsociality occupations, in only one – professional dancer – are women the majority), and much, much more – including the blunt reality that most women will still ignore as a potential mate any man who does earn less than she does.

The situation is further complicated by the way that, in many cases, women simply won’t put themselves forward for higher-paying roles, or won’t ask for the same levels of pay as their male colleagues. An internal recruiter once told me that several times he’d advertised a senior role, specifically targeted for and posted to appropriate women in the organisation, yet none at all had applied; but they did apply when the same role was re-advertised at a lower rate of pay. In other words, there are complexities here that, by definition, are largely out of the hands of men: they can only be resolved by the women themselves – and blaming men simply won’t help in this, because it assigns responsibility away from where it actually resides.

There’s also the very important point that whilst men may earn more than women, there’s no doubt whatsoever that women spend more than men – there’s a huge yet often largely-undocumented transfer of funds from men to women, usually in the home, but sometimes in other contexts as well. (It took marketing-groups a lot longer than it should have done to latch onto this fact – a fault, that, yes, could well have been described as sexist…) This not only renders much of the argument about relative-earnings largely-irrelevant, but also indicates where much of the real yet largely-unacknowledged economic-power actually resides.

— Emma Watson’s much-lauded #HeForShe initiative in principle aims to find a way to resolve that real problem above, that women won’t put themselves forward for higher-earning roles, by, in essence, assigning the primary responsibility to men. She wants “a billion men” to become women’s champions. Although it’s inherently problematic – the respective responsibility ultimately does and can only reside with women – there is a real role that men can play in this, in providing ‘power-with’, in terms of the power-model that we developed in the ‘power and gender‘ post in this series:

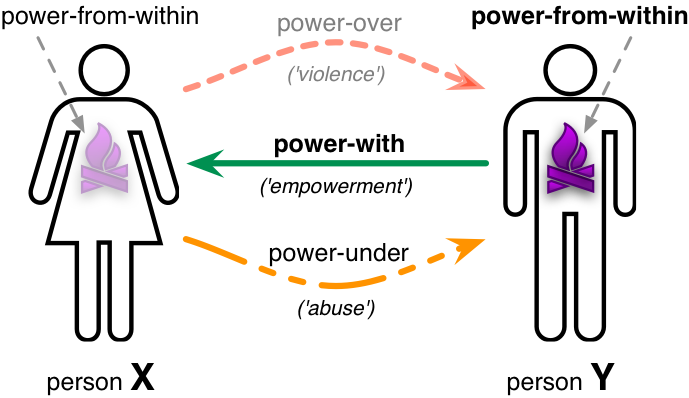

The catch, though, is that it’s entirely one-sided: there’s #HeForShe, but no matching #SheForHe – in fact almost the opposite, that men are being blamed, and that women are therefore supposedly ‘entitled’ to punish them, for something that’s largely a women-created problem in the first place. Hence in terms of that power-model, the reality of #HeForShe looks much more like this:

Or, step-by-step:

- women feel a lack of power-from-within – ‘ability to do work’ – to tackle the work of promoting their own skills and abilities in a social context

- the #HeForShe initiative assigns all responsibility to men for the power to make this happen – which is a form of abuse, ‘assigning responsibility onto the Other without their engagement and consent’

- there’s an implicit blaming of men that this situation (women’s sense of lack of power) currently exists – blame being a combination of power-under assignment-of-responsibility, and power-over ‘propping Self up by putting other down’

- men are required to provide power-with to women, drawing on their own power-from-within – yet without reciprocity, there’s no obvious means via which those men can replenish the power-from-within used up in that power-with process

- the offer from women is that, if the power-with is provided, the current blaming of men for all of this mess may be reduced – but at best most probably replaced by assertions (as we’ve seen in the university case above) that women ‘naturally’ outperform men and are inherently ‘better’ (in other words, yet more denigratory power-over against those same men who’ve just been supporting them)

Hence, when we look at it that way, #HeForShe is inherently doomed to failure, one way or another, even before it starts: in most cases its only likely outcome is that women will gain nothing – because their power is focussed more on blaming and/or assigning responsibility to men rather than on taking responsibility for their own behaviours – and that men will either burn-out – because the power-with is going nowhere, and the power-within is not being replenished – and/or become more embittered at yet another betrayal and anti-male blame-fest.

In short, #HeForShe is something that would perhaps seem like a great idea only to someone who hasn’t looked at the context in anything more than the most Simple of terms, and hasn’t bothered to think it through with anything even remotely resembling a proper whole-of-system assessment. The blunt reality is that structures with built-in inequalities of this type simply do not work – for anyone.

— There are also now many other structural-inequalities, in the sense of explicit exclusion of men’s ‘needs and concerns’. In Australia, there’s the Cabinet-level ‘Office of the Status of Women‘, but no ‘Office for the Safety of Men’, which would be its gender-stereotypic equivalent. (In employment, safety follows women to the exact same extent that status flees them.) In Britain, there’s a Minister For Women And Equalities: apparently equality doesn’t apply to men. In the US, there’s the Violence Against Women Act, but no matching Violence Against Men Act – even though, as we’ll see in the next post in this series, there’s exactly the same need for it. There’s the GirlEffect.org charity, but no matching BoyEffect.org – and some of the claims made in the ‘Why girls?‘ section of the GirlEffect website are somewhere between specious and just plain false. And then there’s space to spend time with one’s own gender: it’s a very real need, in part to have at least some respite from ‘fear of the Other’ – yet in Australia, for example, there is huge funding, often at state or federal level, for almost any kind of female-only spaces, whilst male-only spaces, such as the old ‘men’s clubs’, are now all-but-illegal – on grounds of presumed ‘discrimination against women’. (It is still just possible in Australia to have a male-only space, but only by special dispensation from a formal tribunal.) The list just goes on, and on, and on…

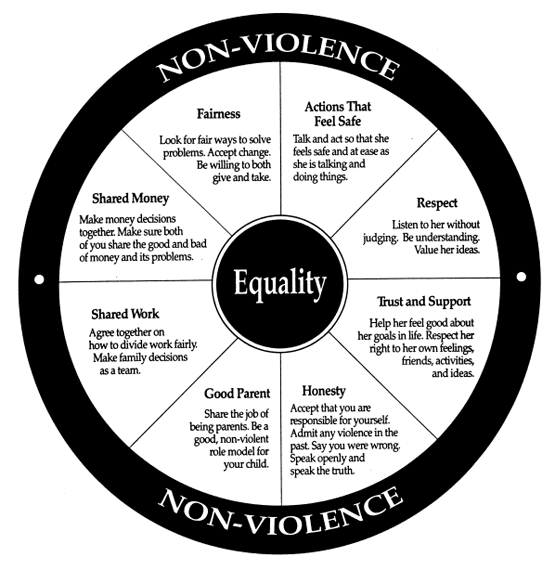

— Finally, let’s note the definitions of equality in the Duluth Model, which we came across in the ‘power and gender‘ post in this series. Here’s the version of the ‘Duluth Wheel’ that describes its mandated outcome of domestic-violence resolution, when true equality is deemed to have been achieved:

Here are the three items of text on that ‘Equality Wheel’ that are perhaps most notable here:

Actions That Feel Safe: Talk and act so that she feels safe and at ease as she is talking and doing things.

Respect: Listen to her without judging. Be understanding. Value her ideas.

Trust and Support: Help her feel good about her goals in life. Respect her right to her own feelings, friends, activities and ideas.

Read that text again: yep, it’s all about her, her needs, concerns, feelings and fears. His needs, or concerns, or feelings, or fears, don’t count, it seems – not only don’t matter, but shouldn’t matter, at all. And that, we’re told, is ‘equality’? Hmm… “Some are more equal than others”, indeed…

Practical applications

(Remember that, in practice, this ‘everyday enterprise-architecture’ part probably doesn’t have all that much to do with gender as such – not least because there are at least two other more-serious sources of mythquakes that could bring the entire culture down at a global scale. Instead, what we’re after here is insights that we can apply right now in our routine, everyday enterprise-architecture practice.)

The single most important insight from all of this is that inequalities are really bad news to any enterprise-architecture. Inequalities of any form will, at the very least, create risks of a shift from mutually-supportive power-relationships:

…to mutually-destructive power-relationships:

… from which no-one wins, and which, if unchecked, drive a downward-spiral into the madness of ‘mutually-assured destruction’. Not a good idea…

Structural-inequalities – such as in so many of the examples above – are probably the worst, because they’re so easily ignored or dismissed as ‘just the way things are’. They’re not ‘just the way things are’, they’re the outcomes of someone’s choice – or, more often, perhaps non-choice, or failure to make a conscious choice – that has led them to be ‘the way they are’. And since it is a choice – and a choice that leads to darn-dangerous outcomes – then it’s up to us as enterprise-architects to find appropriate ways in which that ‘choice’ can be un-made, and more appropriate and more effective choices made instead. (Although our role as enterprise-architects is rarely to make such choices as such, it is our role to provide appropriate support and guidance for such decisions to be made.)

Watch out, though, for special-cases where ‘identical’ is not always the same as ‘equal’. An expectation of identicality is probably the default, but as in all values-concerns, that somewhat-arbitrary ‘ideal’ is always going to be impacted by some form or other of ‘It depends…’. In practice, it’s essential to have some form of anchor-principle such as that used above – “the needs, concerns, feelings and fears of women and of men are of exactly equal value and importance” – though the exact phrasing for the respective principle will necessarily vary according to the context to which the respective form of equality applies.

For a worked example and descriptions of techniques to use for this, see the post ‘Services and Enterprise Canvas review – 3D: Investors‘. In that specific case, it focusses on relationships and balances between stakeholders in a service-context – but because Enterprise Canvas is designed to work in a fully-fractal manner, the same principles apply not just a whole-organisation level, but right down to the smallest possible service-interaction, even down a single line of code. What are the core principles for equality that apply in this context? How do we create and keep alignment to those principles? That questions need to be core drivers and tests in every aspect of enterprise-architecture work.

Note too that equality is a values-concern, and hence directly fits in with the ‘Validation’ section of the Enterprise Canvas ‘guidance-services’ – see post ‘Services and Enterprise Canvas review – 3C: Validation‘. Applying the same generic pattern there to the specifics of equality:

- Develop awareness of the importance of equality to the effectiveness of the enterprise as a whole

- Develop capability to support equality in every action

- Enact support for equality at run-time and in all relationships

- Verify compliance to equality – though always in the sense of continual-improvement, not in terms of ‘punishment’ for ‘transgressions’ or the like

Note also, and importantly, that that this is not just about people: the exact same also applies in relations between machines and IT-systems. Wherever one system is given an arbitrary priority over any or all others, inefficiencies and ineffectiveness will be the inevitable result. You Have Been Warned, etcetera? 🙂

The next and last main post in this series will explore what happens when we don’t handle well concerns such as equality – and what needs to be done in order to get out of and recover from the resultant mess. Over to you for now, anyway.

Leave a Reply