Declaring the assumptions

Moving onward with this exploration of how I’m reframing the way I work, a key part is around identifying the constraints of that work: where and how the tools work, and – perhaps even more important – being clear about where they don’t.

(A key reason it’s important is that, if I don’t describe those constraints properly, well, yeah, that in itself is likely to cause a lot of unwonted arguments, isn’t it? 🙁 )

A key part of that process of framing the constraints revolves around declaring the assumptions upon which that work is based. Once we know what the assumptions are, we have a better chance of knowing where the tools are likely to work and not-work, and also what affordances might or might not become available if and when we use the tools in unexpected ways.

The trick, of course, is in finding ways to surface those assumptions – which ain’t always as easy as it might seem…

(Also, and important, is that this does not imply that anyone who holds different assumptions is ‘wrong’. What it does imply is that people who hold or expect or demand different assumptions than those declared here may attempt to review or use my work in ways for which it was not designed, and hence may not get the results they expect.)

Anyway, here’s how I best understand my own core-assumptions, and the probable implied constraints that might arise:

— I assume that architecture is about how all the elements of a context work together. This includes both structure and story.

Implied constraint: Some of what I describe as architecture – in particular, the human or story-related aspects of architecture – may seem incomprehensible to those who assume that architecture is solely about structure.

— I assume that everything within a context ultimately depends on everything else. Every context or ‘system’ is itself part of a larger context, and also intersects with and/or is seemingly ‘composed of’ any number of other sibling-contexts or sub-contexts. These are foundational concepts in most systems-thinking models, in ecological/ecosystem models, and in cybernetics-oriented frameworks such as Viable System Model – on which, for example, my work on Enterprise Canvas is based.

Implied constraint: From that assumption, it might seem that, in order to do anything with anything, we first have to know everything about everything. That way madness lies… Instead, we acknowledge this as an impossible ideal, yet one we should always aim for, as guided by practical limits – the classic guideline of ‘Just Enough Detail‘. The resultant constraint is that some of my work may be incomprehensible or misleading for those who do not have sufficient capability or experience to work with the implied uncertainties of ‘Just Enough Detail’.

— I assume that everywhere and nowhere is ‘the Centre’ of an architecture, all at the same time, and that every service within an architecture is necessary for the viability of that architecture.

Implied constraint: People who assume or assert that some point or domain will and must always be ‘the Centre’ of an architecture are likely to find key aspects of my work either problematic, or challenging in a political or other sense.

— I assume that every real-world context contains inherent-uncertainties, which must be explicitly acknowledged – see, for example, the ‘enterprise-architects’ mantra‘ – and allowed-for in any architecture and design.

Implied constraint: Key aspects of my work may seem incomprehensible or misleading for those who demand or assume that everything can and must be provable and certain.

— I assume that every purported boundary is in part an arbitrary choice – that, for example, the boundary of a service is whatever we choose the boundary of ‘the service’ to be – and hence that boundaries themselves should always be considered a potential subject for review within any architectural assessment.

Implied constraint: This assertion may be considered problematic, unpopular, impertinent or downright unacceptable to some or many people – particularly those who have vested interests in the purported inviolability or absoluteness of certain boundaries, or who (as above) are uncomfortable with and/or intolerant of any form of uncertainties.

— I assume that, in enterprise-architecture, ‘the enterprise’ is, in essence, an idea or intent, separate and distinct from any organisation or structure set up to act on or with that idea (see slidedeck ‘What is an enterprise?‘).

Implied constraint: Key aspects on my work on enterprise-architectures may seem incomprehensible to those who assume that ‘the enterprise’ and ‘the organisation’ are one and the same.

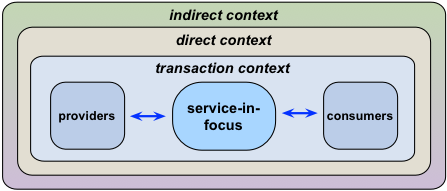

— I assume that, in enterprise-architecture, the term ‘the enterprise’ and its related architectures may relate to and denote any appropriate scope, rather than solely or exclusively some predefined scope. Rather than a fixed scope, I typically assume, or model in terms of, a pattern of relationships between elements in the architecture, with the relevant ‘the enterprise’ extending outward beyond the element currently in architectural focus:

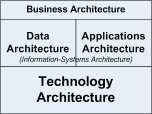

This is in contrast to common assertions that ‘the enterprise’ and ‘the architecture’ relate solely or primarily to the broader or overall operations of a commercial organisation, and/or that the effective scope of enterprise-architecture is delimited by and centred solely around IT-specific architectures, as described, for example by the ‘BDAT stack’:

More generally, I also assume that the same principles of enterprise architecture can be applied at every scale, from ‘really-big-picture‘, right down to a single web-service, and sometimes even-smaller scale than that.

Implied constraint: Key aspects of my work on enterprise-architectures may seem incomprehensible to those who assume the inevitability and exclusivity of some predefined scope and/or scale.

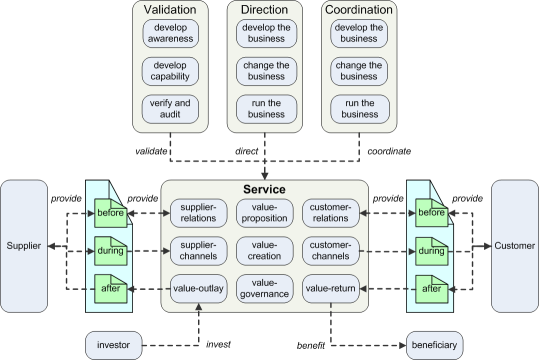

— I assume that architectures may be usefully described in terms of fractal-like patterns, such as the Enterprise Canvas and its use as a checklist for service-viability at any scope or scale:

Or the Five Elements pattern that describes the recursive structure of the project-lifecycle and suchlike:

Or the SCAN framework for fractal-oriented sensemaking and decision-making:

I also assume that any practitioner who uses my work will have – if perhaps with some assistance – the competence and experience needed to adapt such ‘meta-patterns’ into the requisite instantiations for context-specific use.

Implied constraint: People who expect predefined step-by-step instructions for everything, or assume that models must always be different in different contexts, are likely to find key aspects of my work somewhat problematic, or possibly incomprehensible.

— I assume that, when fractal patterns are in use, there may be distinct terminology that follows the pattern more than any context to which the pattern is applied – see the post ‘Fractals, naming and enterprise-architecture‘. For example, in Enterprise Canvas, terms such as ‘asset’, ‘function’ and ‘capability’ have specific meanings that are consistent in every usage of that pattern, but may seem inconsistent when compared with local terminology used in specific business-contexts, because the latter is itself highly inconsistent.

Because of this, I also assume that any practitioner who uses my work has the competence and experience needed to ‘translate’ a fractal-oriented terminology into the terminology used within any given local context.

Implied constraint: People who expect that context-specific terminology will not need ‘translation’ when used in other contexts, or who insist that specific meanings for terms are ‘the truth’, may well find key aspects of my work problematic, or possibly incomprehensible.

—

There’s plenty more I could say, of course, but that’ll probably do for now.

Once again, this doesn’t mean that people who hold different assumptions are ‘wrong’: it’s just that their assumptions may make it difficult for them to get the best use or sense out of my work.

And likewise I’m not asserting that my assumptions are ‘right’, other than in the specific sense that my work does have proven applications and validity in such contexts as these assumptions might apply.

Conversely, other people may be able to see where I’m misinterpreting their work because of these assumptions that I hold, as per above.

Either way, declaring the assumptions does make misinterpretations a whole lot easier to identify and resolve. That’s my experience, anyway. 🙂

Hi Tom,

“declaring the assumptions does make misinterpretations a whole lot easier to identify and resolve” made me think about my own assumption which is that architects almost never get away by just following the simple problem path (the arrows) but they need to cover the whole wicked problem-solving map: https://twitter.com/mapbakery/status/555991516750295040/photo/1

I’m still not sure what the relation is/can be between motes/triples & question/answers and if/how you are going to support my assumption/problem-solving map.