RBPEA: Basics and fundamentals

A small girl in the café this morning, with her parents. All happy enough for most of the time, yet also often an all-too-typical example of the dreaded ‘terrible twos’:

- everything’s ‘Mine!’, even (or perhaps especially) if it was actually someone else’s

- every ‘No’ treated as a ‘Yes’ (unless it was her own ‘No!’, of course)

- refusal to be responsible for or about anything

- everything has to happen right now

- insistent demands to be the centre of everyone’s attention

- and definitely, but definitely, no sharing.

And no amount of telling her to ‘behave’, or whatever, is going to change any of that any time soon – because it is perfectly normal behaviour for a two-year-old. What it’s not, though, is healthy behaviour for anyone any much older than a two-year-old: in general, given the actual social-cognitive drivers of child-development, we’d expect a normal child to start growing out of it by not much more than three years old.

So it’s kinda sad, and worrying, and a lot more, to realise that our much of current cultures, social-structures, and, especially, globalised economics, are built around pretty much exactly a two year-old’s view of the world:

- everything’s ‘Mine!’ – including or perhaps especially if it more properly pertains to others

- every real-world constraint is ignored or overridden, regardless of the real-world consequences

- an insistent focus on the short-term, with awareness of the longer-term often conspicuous only by its absence

- much of the social concepts of power and suchlike revolve around evasion of responsibility

- much of the social concepts of power and suchlike revolve around demands to be the sole centre of others’ attention and activity

- and definitely, but definitely, no sharing – often derided as ‘socialism’, ‘communism’ or downright treason.

Which, exactly as for a two-year-old, is not viable unless someone is willing to take on the more adult role of tidying up the childish mess.

It’s a culture-type that I’d typically describe as a paediarchy – ‘rule by, for and on behalf of the childish’ – and whose structures and strictures inevitably create an economics that is ‘The Worst Possible System‘. But in a culture in which people are massively rewarded for behaving like two-year-olds, and often actively penalised if they don’t, then where are the incentives to act more like an adult? – because someone has to be there to clean up the mess that that ‘kiddies’-anarchy’ makes of everything… The blunt reality is that unless we do end those disincentives, and somehow get everyone to ‘grow up’ at least to the level of a three-year-old, the harsh arithmetic of diminishing-returns and suchlike will send the entire global-economics into a downward-spiral from which even the most paediarchal of ‘adults’ are not likely to survive. In short, Not A Good Idea…

Okay, I’ll admit that on much of this we’re still in weak-signals territory at present, but from my reading of the signs as a professional futurist, it looks like we’re already very close to a non-recoverable tipping-point. The kind of tipping-point, in fact, that shifts from change in which we still have some choices, versus change that’d be forced on us whether we like it or not, and quite possibly in the worst possible way. Yes, I’m acutely aware that the social-changes that all of this implies are already almost impossibly large as far as most people could conceive of them, but again, the blunt reality is that the sooner we get started on this, the more chance of choice we’ll be able to retain. In other words, at present it is kinda still our choice – but not one that we’d be wise to put off for long. Not long at all.

Which is where Really-Big-Picture Enterprise-Architecture – or RBPEA for short – comes into this picture: an enterprise-architecture for the entirety of ‘the human enterprise’ at a literally global scale.

Applying POSIWID – ‘the purpose of the system is [expressed in] what it does’ – then it seems pretty clear that what we have right now is a culture that’s ‘designed’ to dissuade anyone from growing up much beyond two years old, and which, in the longer-term is also drawing us closer and closer to collective suicide because we’re refusing to grow up beyond the possessive temper-tantrums of a two-year-old.

In which case, what architecture would we need to help pull us back from the brink, and create something that actually works?

Taking child-development as a guide, it seems likely that it wouldn’t need to be all that much different from what we already have – yet, exactly as with child-development, there are some crucial shifts in perspective and awareness that must somehow take place before this will work. These include:

- capable of understanding ‘Other’ as equal

- need to share within social-context

- start from needs rather than wants

- awareness of personal responsibilities within a social context

Which, in child-development, is what we’d expect to see starting to happen in a normal three-year-old. In other words, not actually that much of a jump from a two-year-old – no matter how self-obsessed and possession-crazed the latter may be right now. But without that shift happening, with everyone, everywhere, at a truly global scale, we’re dead. Hence why this is kinda important…

In essence, RBPEA is exactly the same as for enterprise-architectures at a more everyday scope and scale – the same core principles, the same core processes, the same core information-flows and more. It’s about sociotechnical systems, yes, rather than solely-technical systems – but the same is true of every other enterprise-architecture anyway. The only real key difference is that the scope and scale are much (much) larger, highlighting constraints and corollaries that could often otherwise be hidden from view; and what’s at stake is much (much) greater, too.

The first fundamental here, perhaps, is Richard Feynman’s blunt warning, in the last sentence of his addendum to the Rogers Report on the Challenger disaster:

For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.

If we don’t heed Feynman’s warning, what we’re likely to get is our own contextual-equivalent of this:

Where it gets tricky is that, yes, we can sometimes get away with ignoring reality: we can continue deluding ourselves, for a while, if we’re foolish enough to do so. That possibility of delusion is a direct corollary of the key assertion from the previous post in this series, that the only absolute rule is that there are no absolute rules.

The possibility for such delusion is especially prevalent wherever people try to apply simple binary true/false logic to statistical uncertainties. Hence, for such people especially, we really do need to emphasise two essential points:

- ‘high-probability’ does not mean ‘will always happen’

- ‘low-probability’ does not mean ‘will never happen’

Or, as Feynman also warns in his Rogers Commission addendum:

When playing Russian roulette the fact that the first shot got off safely is little comfort for the next.

The key point about that paradox of “there are no rules” is that there are still rules – it’s just that there are other things going on as well, all of them intersecting with each other. Consider entropy, for example, the so-called ‘arrow of time’, ‘the winding-down of the clockwork of the universe’: that sounds like an absolute rule, doesn’t it? Well, yes and no, both at the same time, as several of us explored in some depth in the posts and notes on ‘Reframing entropy in business‘ and ‘More on reframing entropy in business‘. For example, living-systems live only because they pull off a remarkable trick, leveraging variances in entropy to create what is, in effect, local reversals of entropy – at a species-level or whole-of-system level, at any rate, if not ultimately so for any individual entity or element in the system.

And the whole thing is fully fractal: the more we try to pin it down, the more confusing it gets… Hence, for example, yes, there is linear-causality – yet that linear-causality also contains non-linear complexities and ‘chaos’ within itself. Rules and algorithms only work well on ‘tame-problems’ – and yet in any real-world context, every seemingly-‘tame’ problem will also include ‘wild-problem’ elements hidden somewhere within it. In the same way, some kinds of ‘chaos’ often arise from simple-seeming rules:, to quote Douglas Hoftstadter, “It turns out that an eerie type of chaos can lurk just behind a facade of order – and yet, deep inside the chaos lurks an even eerier type of order”.

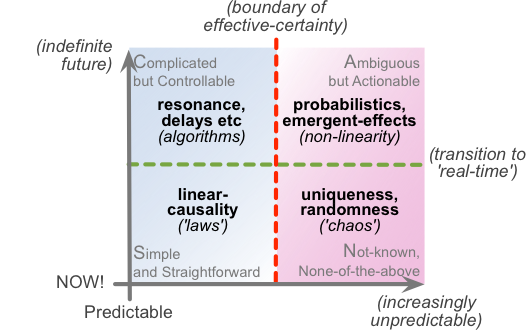

In effect, every point contains every other point, and the impacts of every other point, in a myriad of different ways – only some of which could be said to be certain and predictable. We can use a SCAN crossmap to illustrate the core elements of that fractality:

Hence to work with this point about ‘every point contains every other point’, we need rules and algorithms for the seeming-certainties, and patterns and guidelines and principles for the inherent-uncertainties – as indicated by another SCAN crossmap:

Among other things, what this tells us is that a legal-system based on rules for supposed ‘certainties’ of outcome is never going to work well in the real-world – because in the real world, by definition, there will always be gaps, loopholes, exceptions. Adults learn how to bridge the gaps with responsibility; the ‘childish ones’ hunt for loopholes to evade responsibility, and to enable irresponsibility.

Which means, in practice, that a core requirement for RBPEA is that we need to turn much of the current legal-system on its head: shift the basis of ‘the rule of law’ from rule-based to principle-based – where ‘the spirit of the law’ has explicit priority over ‘the letter of the law’. Apart from anything else, it makes the law much, much simpler to understand and to enact. The ‘letter of the law’ never gains status of anything more than a recommendation or a guideline: instead, we shift the burden onto the defendant (which, ultimately, is everyone, not just one single person!) to explain how an action or inaction supported the principle embodied in the respective law – or, if not, what could be done to bring actions back more into line with that intent.

What’s interesting is that that shift in emphasis creates almost no difference in any context of adult responsibility. What it does do, though, is cut off almost all avenues for game-plays via ‘legal-loopholes’: it mandates adult-responsibility, rather than – as with present rule-based law – providing all too much support for childish evasions of responsibility.

Another aspect of this is that a viable RBPEA needs to make it clear that responsibility pertains to everyone – not solely to those who can’t (mis)use the law to help them evade their own part in the mutual interlocking responsibilities that make a social and economic context work. For example, we need to make it clear that there is no right to not-care: not-caring is not something to be considered praiseworthy – as it too often is at present – but rather as a symptom of a serious social-development disorder known as sociopathy.

Likewise – though this still seems to be way too far into the too-hard basket as yet for most people to be able to comprehend – a necessary corollary of “the only absolute rule is that there are no absolute rules is that in a viable economics there are no ‘rights of possession’. Structurally speaking, ‘rights’ are just another kind of rule, and possession itself is little more a two-year-old’s view of the world, not an adult’s – as is indicated in that more-than-a-hint of dysfunctional childishness behind every possessive cry of ‘Mine!!!’. Instead, we need to shift to a stewardship / responsibility-based model of ownership: we ‘own’ something because we take responsibility for it, not because we have purported ‘rights’ to ‘possess’ it, regardless of whether we care for it or not.

(On the surface, a responsibility-based economics looks much the same as a possession-based one: people still ‘own’ items of ‘property’, and suchlike. The big difference is that the focus shifts from the ‘wants’ and demands of the individual to the genuine needs across the whole broader collective; from the ‘rights’ of the ‘possessor’ to the maintenance and viability of the social-economy as a whole; from the self-obsessed two-year-old to the calm considered relations between aware adults. Among other things, this immediately invalidates the scarcity-games and hoarding so common in current economics, that are in turn the direct cause of so many of its dysfunctions. More on that in a later post, anyway.)

One of the corollaries of that point is that everything built on top of ‘rights’ of ‘possession’ is inherently invalid in and/or irrelevant to a viable responsibility-based economics. The fundamental fact here is that there is no way to make a possession-based economics viable or sustainable. (The only way it can be made to seem to work is as an infinite pyramid-game – hence the endless obsessions with ‘growth’ and suchlike, which is merely a means to delay facing the fact that the fundamental economics doesn’t work. The blunt fact is you can’t have infinite growth on a finite planet, or anything else with effectively-non-negotiable limits – and we’re hitting harder and harder up against those limits right now…)

What this should tell us straight away – though seemingly very few people have got the message as yet – is that futzing-around with trying to fix up the finance-system or the banking-system or the currency-model or barter-type models is inherently a complete waste of time, effort, energy or anything else. Because all of them are built on top of ‘rights of possession’ – which not only doesn’t work well, but actually cannot work well, if at all – we really do need to stop wasting our time with every one of those inherently-futile fudges and fix-ups, and get on with the real task instead. And that’s that the failure-point is so deep and so fundamental that the only realistic and viable option is to scrap the whole darn lot – scrap the entirety of possession-based economics – and start again from what does work, namely interlocking mutual responsibilities. We could summarise this visually as follows:

Ultimately, as I’ve also explained in some depth in various RBPEA posts, we need to understand that there are no rights – the entire concept of ‘rights’ needs to be reframed, from ‘rules’ imposed on others for personal benefit alone, to, again, interlocking mutual responsibilities across the entirety of the socioeconomic system. Popular though they are with so many people, in reality the entire ‘rights’-discourse is a dangerously-misleading paediarchal delusion: we need to shift the discourse from from a childishly self-centric ‘What are my rights?’ to a more adult wholeness-aware ‘What is the overall intent and need?’.

I’ve overrun as usual, so probably best stop here for now, although there are several other key themes for RBPEA that I need to address in further posts, such as:

- feelings as facts

- the dangers of ‘anything-centrism’

- object-based, subject-based and ‘should’

- wants and needs

The core point to understand, though, is that all of those themes described above fit into that general category of “you can’t argue with physics”. Reality Department has been making it very clear for a long time now that all of them either are or derive directly from non-negotiable constraints imposed by Reality Department itself: and as per that Feynman quote earlier, “nature cannot be fooled”. If we think otherwise, we’re only fooling ourselves…

Or, to put it into a more direct architectural context, any large-scale architecture that ignores any of the themes above will be non-viable and/or non-sustainable, and will fail over the longer term. You Have Been Warned…?

More soon on these themes, anyway.

Tom, there a couple of things that I really like about this post, because (and I may have missed these in earlier writings) they are pointing toward alternative views, and parts of the foundations for a mirror image system that might be able to attain coherency viable.

For instance, the idea of spirit of the law vs. letter of the law is a simple conceptual flip, which could be accomplished in fairly short order, with a high-fidelity amplifier (in the homeostatic sense of the word).

Responsibility-based ownership is also powerful. It helps me with a previous problem I had when I perceived that you were advocating that no one owns anything, which seemed like a recipe for 2-yr-old-istic anarchy.

The way I’ve been phrasing a similar idea (I think?) is that the “relationship of possession goes both ways”. Or maybe I’m thinking “ownership” in your terms. The basic idea is that the more one possesses (owns?), the more that person is owned by those things (securing them, maintaining them, traveling around to visit them (that cabin by the lake, that resort condominium, that collection of antique automobiles, that yacht, etc.))

Now, don’t get me wrong. I have no problem with the existence of yachts. I’d actually like to have a whiteboard chat with you on a yacht sometime, which I think would be conducive to some excellent ideation. Where I get stuck is in designing a system where talented yacht-builders would be motivated to create such items without the buyer/owner of such a “possession” in mind. But then I think about Airbnb and Uber, and I think maybe some institutional structures are coming into being, that through various mash-ups and mutations are starting to move in a useful direction.

Ya think?

Glad you found this useful, Doug – many thanks. 🙂

@Doug: “It helps me with a previous problem I had when I perceived that you were advocating that no one owns anything, which seemed like a recipe for 2-yr-old-istic anarchy.”

Yeah, I can see all too well how that kind of impression can arise. I’ve actually been very careful throughout these years about drawing a distinction between ‘kiddies’-anarchy’ – the 2yr-old version (perhaps best typified by a self-styled ‘anarchist’ at college a few decades back, who asserted that “all property must be liberated – but don’t you dare touch my stuff!” 😐 ) – versus real-anarchy, the kind of responsibility-based model typified by the Diggers or, in more recent centuries, the Quakers. ‘Kiddies’-anarchy’ is what we definitely don’t need; the Quaker-style anarchism is what what we do need.

@Doug: “…relationship of possession goes both ways”

In other words, people possessed by their possessions, almost in an exorcism-level sense? – yes, exactly. Yet what works is not a rejection of ownership-responsibilities either: that way leads to another variant of ‘kiddies’-anarchy’, one dominated by the delusion that everything is Somebody Else’s Problem. Instead, it’s closer to a proper interpretation of the Buddhist concept of ‘non-attachment’, where non-attachment is also, at the same time, non-detachment. It’s another one of those fractal-paradoxes – subtle in some ways, yet crucially important.

@Doug: “Where I get stuck is in designing a system where talented yacht-builders would be motivated to create such items without the buyer/owner of such a “possession” in mind.”

Yeah, understood. My understanding of it is that people would continue building boats anyway, in a quite literal sense of ‘whatever floats your boat’. 🙂 And I do see some people taking that all the way to a yacht, or more – some of the ‘big-rig’ ships, for example. The difference would be in how it’s used: not solely as ‘a plaything for the rich and powerful’, but something that many more people could enjoy, as an expression of who they are. (Another comparison example: think of all the people working as volunteers to keep a steam-railway running: the question “Who owns this?” gets very messy unless you think of it in terms of responsibility-based ownership.)

@Doug: “But then I think about Airbnb and Uber…”

Ouch. – because when I think of Airbnb, and even more of Uber or Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, I see a system in which all of the risks are carried by largely-powerless individuals, and most of the profit ends up in the hands of the coordinating-company’s shareholders, who take no risks at all (other than the inanities of hype-bubbles, but that’s another story). In short, I don’t so much see Uber as an example of responsibility-based ownership, but potentially some of the most exploitative and dysfunctional end of capitalism-gone-wrong – in other words, exactly what not to support here… True, there are some aspects of it that are probably worth retaining in various future “mashups and mutations” – the structural/organisational model for crowdsourcing, for example – but the one-way-profit model is definitely something that we need to drop out of the picture (or drop it down into the sewer where it belongs, to put it bluntly). Rant rant rant – well, you know what I mean, anyway… 🙂

Dunno, Tom, guess I have to do deeper research. My understanding of the Uber model is that it bypasses the taxi company normal business models, and the company owns the vehicles and lease them out to drivers, or do a fare split, with drivers rotating to keep the cabs on the road more of the time. http://yourbusiness.azcentral.com/taxicab-companies-make-money-12180.html

Uber says their fee is 5%-20%, and the driver owns the car and makes the “subsystem” of driver and car available at the driver’s discretion. https://get.uber.com/drive-uber/sacramento/p2p/?utm_source=AdWords_Brand&utm_campaign=search|mobile|drivers|sacramento|country-1|city-41|keyword_uber|matchtype_e|ad_69616133320|sitelinks1&utm_medium=kenid_7fea22f0-a09c-5c48-5aa3-0000670f4443&gclid=CjwKEAjw9bKpBRD-geiF8OHz4EcSJACO4O7T58_xpDrvOHAFrg6mriEBcet-pCemYYS1Asjs_heUsBoCugzw_wcB

A few cities have the taxi medallion system where there is a huge capital investment for the privilege of being a driver, and at least in the NY system medallions, though issued by the city, are traded (sold and resold) on a kind of open market.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxicabs_of_the_United_States

This seems to me to be a good test case for an alternative system for getting around a city on a point to point and ad hoc basis, while adhering to some version of the non-possession, non-2-yr-old model. Can we envision a dispatching system, small payload vehicles, drivers (until and unless driverless vehicles become the norm), vehicle maintenance, fuel, insurance (?!) are provided, with no money or currency system, and no possessive ownership? Seems like a fairly simple and accessible brainstorming exercise, no? I suspect that, as much as you’ve thought about this you’ve already done this, and maybe even blogged about it.

Sorry, I meant to say “taxi company normal business models, WHERE the company owns the vehicles”

Hi Doug – apologies for the delay in replying, I got kinda distracted… 😐

Agreed about the taxi-medallion system, and how that gets seriously dysfunctional – we had something similar in Melbourne, as I remember. (A friend in a theatre-group we were in together was later murdered in his own taxi by a couple of hyped-up kids, so I ended up learning quite a bit about the system there, and how well it didn’t work…) But whether Uber is much of an improvement is to me somewhat in doubt: pretty much all of the safeguards that the city-run system should provide are absent for pretty much all of the players – drivers, passengers, police, pedestrians, whatever – except for Uber itself, which seems to have ‘rights’ but not many responsibilities.

As you say, this seems to be a good test-case for developing an alternative that actually works. There would probably be some Uber-like elements – despatching at a city-wide level rather than company-specific, for example – but to me the core is that it needs to start from the mutualities and interlocks between the respective responsibilities. It’s that kind of shift in perspective that I’m really talking about here.

Excellent post, Tom. It describes what’s going on in our (US) government and our commercial institutions today pretty accurately. It’s somewhat galling to me that the people running so many institutions that purport to provide value predicated on enlightened self-interest are happy to leap on concerns de jour, such as income inequality or religious freedoms that allow adherents to religions abridge the freedoms of those who aren’t, to solidify or amplify or cement their own personal wealth and status. It’s scary, but US society is indeed operating at that two-year-old level and very little seems to be on the horizon to change it. One of the things you didn’t address (but might in the future) is how self-perpetuating this all is.

Thanks, Howard. And yep, that’s a pretty good description of way too many social, commercial and other institutions these days. It applies pretty much everywhere, too: the problems might sometimes seem especially severe in the US, but that’s probably only because the symptoms and causes are more visible there, whereas in other countries they can often be more covert – sometimes all too literally under pain of death.

@Howard: “religious freedoms that allow adherents to religions abridge the freedoms of those who aren’t”

Yes, exactly. That’s something I’ll explore in a bit more detail in the upcoming ‘Feelings are facts’ post. (The connection should be more clear by the time we get there.)

@Howard: “One of the things you didn’t address (but might in the future) is how self-perpetuating this all is.”

It’s self-perpetuating as long as a) someone is still willing to tidy up the ‘kiddies’ mess, and/or b) the game-players can continue to hide the symptoms via the illusion of ‘growth’. Once enough people get fed up with tidying up after the ‘kiddies’, and/or the overall system hits up against non-negotiable constraints, the whole game will break down.

The catch is that whilst it’s going into the breakdown, the ‘kiddies’ will become ever more and more strident about forcing everyone else to tidy up their mess – quite possibly with full-on military force and re-establishment of more-overt forms of slavery. My main aim here, with all of the work on RBPEA, is to establish awareness that there are viable alternatives to ‘kiddies’-anarchy’, before the implosion of the possessionist pyramid-game – which is already getting started now, in fact has been for perhaps four or five decades already – gets much further towards the slavery-scenario. We have some time still left – I’d estimate perhaps maybe even a couple of decades before we must get fully started – but the changes it demands are so huge and so fundamental that in practice it really doesn’t leave us much time at all. Already changed status from ‘Important’ to ‘Urgent’, is another way to put it.

We can’t do it all (understatement of the century?), but we can at least do what we can, yes? 🙂

On another point, could you say more about your understanding of the Quaker business model? I don’t have a clear understanding, but I didn’t think that denomination had a vow of poverty or such.

By the way, my “favorite” 🙂 president of the USA (Richard Nixon) was a Quaker. Long personal story there, for another time.

Ah. For Trickie Dickie to describe himself as ‘a Quaker’ would be like Josef Goebbels describing himself as ‘a family man’ (see the film ‘Downfall’, about the last days in Hitler’s bunker…) – there is some level of truth in it, but so far distant from the actual principle that it’s not so much a stretch as a very, very bleak joke….

The core of the Quaker approach to business is personal responsibility, in every sense of the term. Some of the better-known firms include Cadbury’s (chocolate), Rowntree’s (ditto), Fry’s (ditto) and Barclays (banking – before they were wrecked in recent years). There’s a useful summary of Quaker business and business-ethics at http://www.leveson.org.uk/stmarys/resources/cadbury0503.htm

Here is a discussion about the nature and definition of money that has just started, and might prove interesting: http://goo.gl/zv2jKq