Hidden risks in business-model design

There are a fair few business-model patterns out there that look really great, really profitable – and yet conceal fundamental flaws that can kill the business outright.

(Or, in some cases, it’s not just the business that gets killed… – yep, this yet another all-too-real You Have Been Warned item, folks…)

So how do we spot those risks, those traps?

The short answer, unfortunately, is that we probably won’t be able to see them at all with any standard business-centric business-architecture tool such as Business Model Canvas or the like. Instead, as I described in the previous post here, we’ll need a much broader concept of business-model scope before those risks will come into view.

I was reminded of this the other day when I saw this Tweet from Alex Osterwalder:

- RT @AlexOsterwalder: 7 Questions to assess your business model mechanics #bmgen http://t.co/lbjY47wyrj

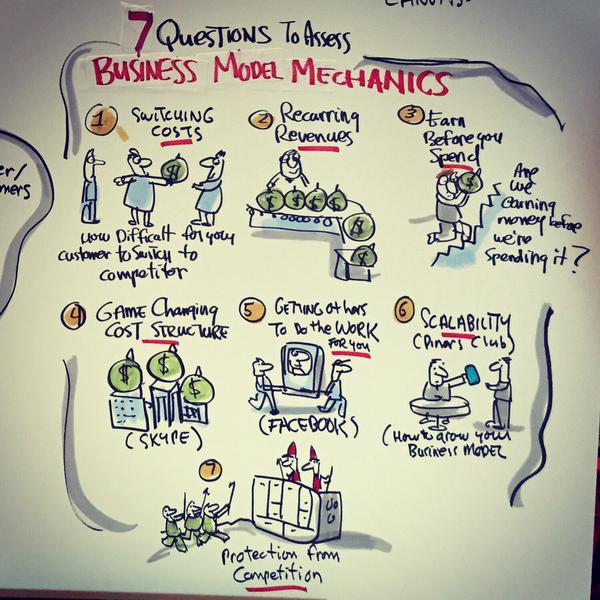

Which pointed to this graphic – presumably by someone doing sketchnotes for one of Alex’s sessions:

Which in turn seems to refer to this blog-post by Nabila Amarsy on Alex’s Strategyzer website:

Which, as per the graphic, describes “seven questions to assess business-model mechanics”. And from those seven items, Alex wrote a follow-on blog-post, expanding on item #5, ‘Getting others to do the work for you’:

Which, unfortunately, falls right into the trap I warned about at the start of this post. In fact, at the surface-level, at least some of his advice there is exactly what not to do if we don’t want our business-model to blow up in our faces in classic ‘pass-the-grenade‘ fashion…

Yet given that Alex is one of the best in the business-model business, what on earth went wrong?

The short answer here is that, in that post, Alex used only Business Model Canvas on its own to describe those business-models – and BMCanvas, useful though it is, just doesn’t cover a broad enough scope to see where those lethal booby-traps lie. If we want to avoid those traps, we must go wider.

Let’s start with the everyday example of shopping for food and suchlike – what’s known in the trade as FMCG (Fast-Moving Consumer Goods).

Back when I was a kid, almost all of the food-shops here in Britain were small and local, and food-shopping was done every day – which it needed to be, because there was no fridge, no freezer and not much storage-space. If you were shopping, you didn’t pick anything yourself, in fact you weren’t allowed to – the shop-assistant did all of that for you instead. And some at least of the shopping would have been delivered for you, by the baker’s-boy, the butcher’s-boy, the milkman or whoever. There wasn’t that much choice, and food was quite expensive, too – with fixed prices for most branded things, the same in every shop.

But as described in the recent BBC series ‘Back In Time For Dinner‘, come the 1960s, the 1970s, suddenly it’s all-change-here. Fridges and even freezers become commonplace, there’s the end of government-mandated Retail Price Maintenance – those fixed-prices – and up comes this real revolution in shopping: the supermarket.

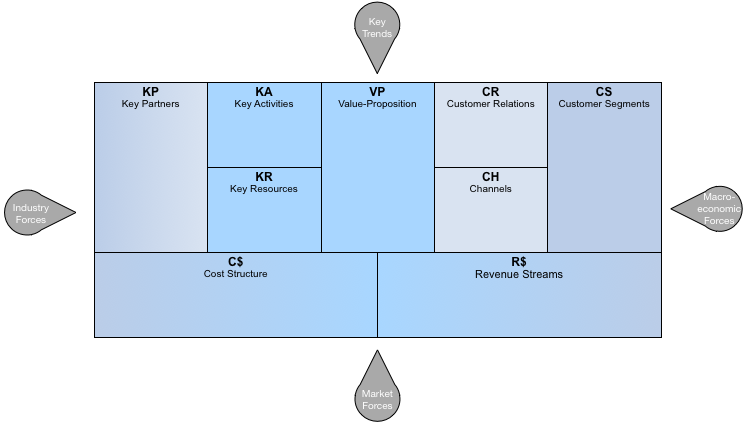

Supermarkets were an instant hit – and using BMCanvas and its accompanying Value Proposition Canvas [VPCanvas] – the white square and circle in the diagram below – it’s quite easy to plot out why:

Relative to that list of ‘7 Questions’ in the sketchnote earlier above, we can clearly see the impact for supermarkets of #4 ‘Game-changing cost-structure’ and #2 ‘Recurring revenues’ and a certain amount of #3 ‘Earn before you spend’ – because suppliers were only paid after quite a big delay. Item #7 ‘Protection from competition’ came mostly from the high investment-costs and complexities not just of the stores themselves but the logistics-operations to support them. Once that logistics-structure is in place, then it becomes much easier to apply #6 ‘Scalability’, and grow in scale – with profits to match.

For the customer, it’s not just that the prices can be lower, from economies of scale and the like: there’s much more choice, and the shopper has the sense of personal-choice too, selecting items on their own, rather than having to explain everything to an assistant. Customer-relations are somewhat different – connecting via brands promoted in mass-media, rather than person-to-person relationships. Yet the big change is in item #5, ‘Getting others to do the work for you’ – that the customer does much of the work, selecting and collating the goods, and then carrying them home.

For a while, supermarkets were hugely profitable – and one supermarket could put a whole High Street of small shops out of business almost at a stroke. Even on its own, that BMCanvas / VPCanvas pairing can show exactly how and why that would happen.

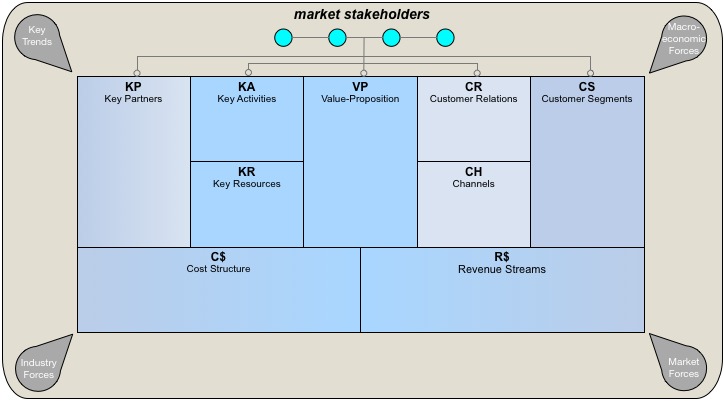

But to understand what happened next, we need one of Alex’s lesser-known add-ons to BMCanvas, the Environment Map:

The one-line summary here is that if something’s hugely profitable, it ain’t gonna be long before someone else finds a way to barge in on the act. Item #1 ‘Switching-costs’ have always been low in FMCG, whilst the shorter-term #7 ‘Protection from competition’ quietly faded away – and suddenly that business-model becomes not quite so profitable any more…

Yes, food is very cheap now, compared to what it used to be, and much more plentiful too – and supermarkets have played a major part in that. But the cost to the supermarkets themselves is those gains all round have largely arisen from a race-to-the-bottom in terms of pricing and more (we’ll look at the “and more” bit in a moment). The reality now is that although sales-volumes are still huge, margins are razor-thin – and supermarkets need every scrap of competitive-advantage they can find.

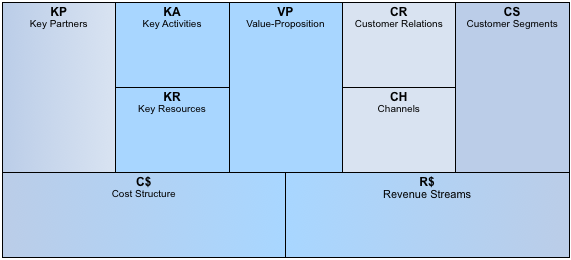

In part, we can gain competitive-advantage by looking inward at the operational fine-detail of the business-model. For that, we need to take what we’ve mapped out on via the raw BMCanvas:

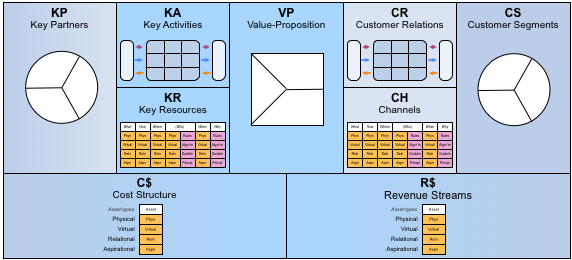

And from there, expand it inwards (‘zoom-in’) to the fine-detail that we need for an implementable enterprise-architecture:

The core concern here, as I warned in the post ‘Why business-model to enterprise-architecture?‘, is that:

Real-world detail can break the best-looking business-model without even breaking out a sweat. We need to know that detail – or at least have a better sense of that detail – before committing ourselves and others to a lot of hard work and ultimate heartache.

Yet a valuable side-effect of that type of in-depth exploration is that it will usually turn up new options that we can leverage in the overall enterprise-design. Hence, for example, the crucial business-advantages to be gained from IT-based automation and track-and-trace throughout the supply-chain, or the subtle marketing-based arts of shelf-placement-at-a-fee for brands, and aisle-planning to maximise unneeded-but-wanted impulse-buys. (We might note that none of these tactics occur on that ‘7 Questions’ list…)

But to tackle the larger-scope changes, and to respond to them in time, we need a solid grasp of futures – a ‘zoom-out’ again to themes such as market-forces, industry-forces, macroeconomic-forces and key-trends, as per Alex’s Environment Map. Hence there’s been the macroeconomic trend towards private-car ownership, supporting the even larger out-of-town hypermarket, with the huge weekly shop that can only be carried by car – more costs carried by the customer. More recently, there’s been the development of self-checkout – reducing the checkout-queues by passing the work of checkout to the customers themselves.

Provide the economies-of-scale, and you’ll get the customers to do the rest of the work for free! Profit all the way! That’s what it looks like, doesn’t it?

Not quite – because it’s actually very fragile. The challenge isn’t just competition against other big supermarkets: if we lose any of those factors that make it work, the entire business-model becomes at risk – and many of these key factors are mostly outside of our control. What happens to out-of-town shopping when cars get too expensive to run? What happens when we offer too much choice, such that smaller-scale supermarkets can seem less overwhelming? What happens when there’s loss of trust after food-tainting scandals in the supply-chain? Right now, what we see happening is that the big supermarkets are increasingly losing out to small chains, to local mini-supermarkets, and even to small specialist stores – so much so that in many medium-sized towns there’s been somewhat of a revival of the supposedly ‘old-fashioned’ High Street.

One of the most interesting challenges is the rise of online grocery-shopping. At first glance this looks great to the supermarket: even more of the work passed on to the customer – and no need to provide parking-space, either! But as summarised in the final episode of the BBC’s ‘Back In Time For Dinner’ series, looking forward at “how we’ll shop, cook and eat over the next 50 years”, the catch is that it cannibalises almost all of the ‘free-labour’ that the in-store customer would already provide: for online-shopping to succeed, the supermarket has do the picking from the shelves, collection of all the items into an order, the final checkout and billing, and probably free-delivery too. On top of that, the store will probably lose most of the in-store customer’s impulse-buys of high-margin items like pastries and chocolate that provide so much of the actual profit. For some of the big supermarket-chains, online-shopping is turning out to be very bad news indeed…

(There’s an interesting parallel here with what’s happened in the book-trade. A few decades back there was the sudden rise of the big book-chains – Borders, Waterstones, Fnac, Dymocks and so on, depending on which country you’re in. Their business-model was that, with the end of fixed-pricing for books, they could offer a wider range at lower prices – and almost at a stroke, they wiped out most of the smaller book-stores. (The background-context for the story-line in the romantic-comedy film ‘You’ve Got Mail‘ describes this period quite well.) The few small stores that did survive did so by providing services that the big-stores could not – such as deep specialist-knowledge and in-person service. But with the arrival of Amazon and suchlike, and ebooks too, the big-bookstores found themselves stuck in the middle: higher costs, higher prices and less choice than online, but not enough personal-service to stand out. Now it’s the business-model of the smaller-bookstores that’s looking healthier: back to the High Street again – especially in extreme cases such as the Welsh Border town of Hay-on-Wye. Interesting times indeed…)

But let’s get back to that note above about “a race-to-the-bottom in terms of pricing and more” – and in particular the “and more” part, because that’s where the real booby-traps reside. To make sense of these, we’ll need to ‘zoom-out’ from the BMCanvas / VPCanvas pairing:

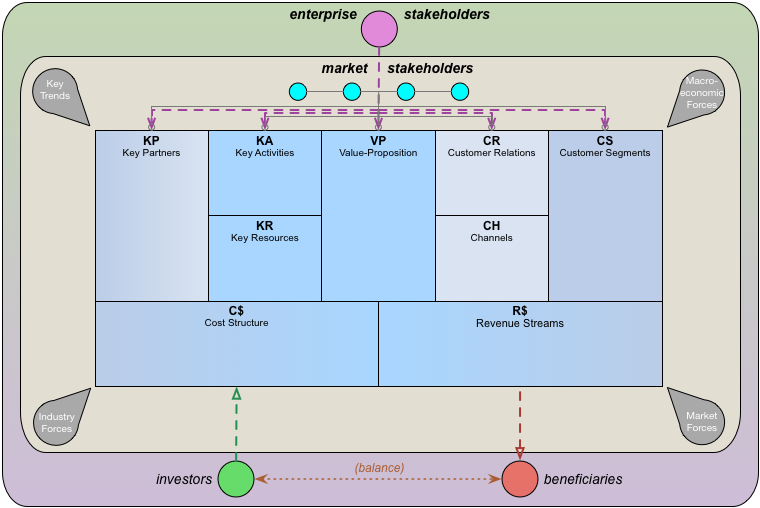

And beyond Alex’s ‘Environment Map’, to at least a whole-of-market scope:

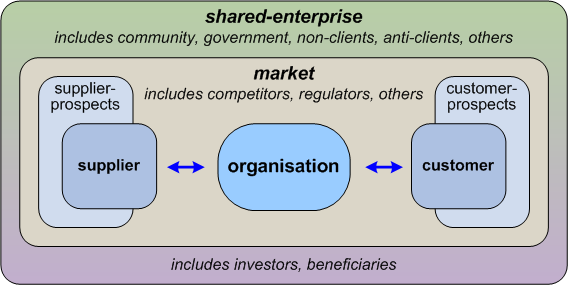

Or, more probably, all the way ‘upwards and sideways‘ to a whole-of-shared-enterprise scope:

The crucial point to understand here – and yet which many business-folk seem, scarily, still unable to comprehend – is that all business depends on trust. The catch is that, even though it’s the central requirement for all business, the factors that affect that trust are not mapped at all in business-centric tools such as BMCanvas – and barely rate a mention even in more customer-oriented tools such as VPCanvas. Oops…

To illustrate the point, some of the most crucial stakeholders for a business are its non-clients and, even more, its anticlients:

Non-clients and anticlients don’t appear in the standard transaction-type business-model, precisely because they don’t transact with it. Yet they do interact with, indirectly – that’s the difference. And because they do interact with the overall business-model, we need to know about them – and, in particular, about how they can impact on that crucial element of trust.

Non-clients don’t transact with the company, but they can influence how others interact and transact with the company – ‘others’ such as the company’s current and prospective customers, suppliers, regulators and others. If their trust is lost, they’ll at best be dismissive and disparaging about the company.

Anticlients have already lost trust with the company – typically because they feel betrayed and/or disgusted by something that the company has or has not done. Unlike non-clients – who are relatively passive in this context – anticlients will actively seek to dissuade others from trusting the company. The costs to the organisation can be huge, yet often most of those costs are at first not measurable in monetary terms – and by the time that they are measurable in monetary terms, much of the damage has already been done. Even for a simple business-model, it’s not a risk that we can afford to ignore; for a business-model for a supermarket or suchlike, it definitely needs to be a high-priority concern.

Happy clients tell a few people that they’re happy – hence the concept of Net Promoter Score so beloved by marketers everywhere. Yet angry anticlients will tell a lot of people, and their reach via social-media is often far greater than we could ever afford to counter via any conventional means of marketing – hence in many cases it’s not Net Promoter Score that we need to worry about, but our anticlients’ implicit Net Demoter Score.

Which brings us back to that list of ‘7 Questions’, and specifically to item #5, ‘Getting others to do the work for you’ – because if there’s one consistent cause of betrayal of trust, that would be it. We might think of this solely from our own perspective, as ‘getting others to do our work for us’: but the common term for ‘using people’s labour for free but not sharing the value’ is ‘slavery’… – probably not a wise idea to base a business-model on that?

It’s not quite as bad as that, fortunately: there are valid ways of ‘getting others to do the work’. (Though probably none that would support a one-sided ‘getting others to do the work for you‘… – a rather important distinction.) The crucial point to understand is that the phrase ‘there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch’ applies to organisations as much as it does to their clients. By now, most internet-users are aware that if some online-service purports to be ‘free’, then it’s probable that they themselves – or, more usually, their attention and/or their data – is the ‘product’ that is being sold on to someone else. Yet scarily-few businesses seem aware that the inverse applies equally to them: that if they’re expecting customers or suppliers to do some of the work ‘for free’, they’d better offer something of value in return – or else they’ll erode away that all-important trust.

In effect, the danger here is of an imbalance between investors and beneficiaries. Customers, suppliers and others who provide their effort or attention need to be understood as investors in the organisation and its business-model – which means that, for balance, they need to be respected as investors, and treated as beneficiaries, too. If we think that our business-model entitles us to translate their investment into money that we then keep solely for ourselves, then we have a business-model that’s literally built on assumptions of ‘right’ to enslave others – which is Not A Good Idea…

So to make that kind of business-model work, there must be some form of valid return for that ‘work-for-free’ investor-as-beneficiary. The return does not necessarily need to be in monetary form – in fact it usually isn’t, other than as prices that are lower than they would otherwise have been. But whatever form it takes, that return must be seen as ‘fair’ – otherwise that downward-spiral of decaying trust becomes almost inevitable. And it must be seen as ‘fair’ by all parties, all stakeholders – not just the transaction-oriented customers and suppliers, but by the regulators and others in the market, and also by those non-clients and anticlients further out in the shared-enterprise.

(Sure, it’s all too easy to set up some kind of short-term scam that short-changes everyone else – but in any true open market, doing so will always come back to bite somehow, especially over the longer term. And yes, there are ways to rig the market too, to try to dump those risks on everyone else – but the global megatrends are such that even those large-scale scams are looking a lot more risky than they user to be, back in the days of the ‘robber barons’ and their latterday ilk. Again, it’s increasingly Not A Good Idea…)

There are many good examples of models that do succeed in getting the balance mostly-right. IKEA, for instance: the customers do quite a lot of the work – picking, selecting, checking-out, transporting, assembling – but they also do get real returns, not just in lower prices, but also in terms of design and materials that are higher-quality than would otherwise be achievable at the price. Customer-service at the UK telco giffgaff is not provided by the company, but by volunteers amongst their clientele – but there’s payback for the ‘free labour’ in the form of more call-minutes and other team-only special-deals. Much the same for volunteers at shows and concerts, in charity-fund-raising and charity-shops, and so on elsewhere: the payback may not be in monetary terms, but there is a payback – otherwise the whole enterprise breaks down.

There’s one special-case of which we need to take especial note: any business-model that aims to build a platform upon which others will depend in various ways. There are a lot of these platforms around, especially online: Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, the various app-stores and so on. Likewise most banking, of course, or the credit-card companies – Visa, Mastercard, Diner’s Card and the rest. Many of these are built around complex multi-way business-models – and yes, some of these are at such scale that they can indeed “make billions”, as per the title of Alex’s article linked-to earlier above. The catch is that the relationship with others in this type of business-model is more like ‘citizen’ than ‘customer’ – and needs to be respected as such. If we don’t offer that respect, and the respective benefits and returns that go with it, the business-model will fail over the longer-term: it really is as simple as that.

One shift in perspective that’s essential here is to realise that we can’t ‘possess’ a platform: as a business-model, it only works if demonstrate that we can and do act as custodians for that platform, responsible to and about every other user of that platform. If we can’t demonstrate such respectful custodianship, users will migrate to another platform – no matter how much we try to block them from doing so with high switching-costs (item #1 in that list) and so on.

In that sense, I worry quite a bit about several of the players in the current platform-space. Amazon and Apple, for example: there’s simply no commercial justification for the huge margins that they charge on their platforms – and, as an active hindrance to free trade and more, they’re increasingly at risk of anti-trust lawsuits and suchlike, with potential for forced break-up of the business. There are other forms of non-monetary misuse: for example, it seems PayPal recently announced a unilateral change to its ‘Terms and Conditions’, in which its US customers must now accept advertising-emails and phone-calls from ‘PayPal partners’ – in other words, other companies to whom PayPal will sell their private information. US customers have no means to opt-out of this: they either accept being bombarded by junk-mail, or lose their means to do business. Ouch…

In effect, this treating platform-users not as citizens, but as bonded-serfs: I can hardly think of a quicker way to create an entire nation of anticlients, who will do anything to break free of that kind of enforced-abuse. Not a clever move, folks: in this context especially, it’d perhaps be wiser to reframe ‘Terms & Conditions’ as ‘Trust & Commitments’ – or, at the very least, think a lot more carefully about the real implications of those ‘citizen’-type relationships.

As a last practical suggestion on this, perhaps take a look at the post ‘Costs of acquisition, retention, de-acquisition‘: it provides step-by-step processes and checklists to test and verify these aspects of the business-model and more. Don’t Leave Home Without It, perhaps? 🙂

Hope this is useful, anyway – and over to you for comment, if you wish.

Tom, the term I find useful to think about these sorts of issues is “moral hazard”. I’m thinking that it is potentially very broad, and at the same time almost universally ignored — or even seen as a positive thing. It came into prominence briefly around the 2008+ melt-down, under the rubric of “too big to fail”, but that kerfuffle has largely died down while the underlying issue is growing again, faster than before. Thoughts?

‘Moral hazard’ – yeah, I’d forgotten that term, and yes, strong agree, it definitely applies, and it’s been all but forgotten of late (as in my case, too… 😐 ). Hmm…

Agreed also, unfortunately, that “the underlying issue is growing again, faster than before”: ‘unfortunately’, because it’s a very real worry… The behaviour is to be expected, I suppose, in a culture that so evidently believes that ‘power is the ability to avoid work – but worrying, to say the least. Watch This Space, I fear?