Services and disservices – 2: Education example

Services serve the needs of someone.

Disservices purport to serve the needs of someone, but don’t – sometimes through incompetence or failure in operation, sometimes through incompetence in service-design, and sometimes even by intent.

And therein lie a huge range of problems for enterprise-architects and many, many others…

This is the second part of what should be a six-part series on services and disservices, and what to do about the latter to (we hope) make them more into the former:

- Part 1: Introduction (overview of the nature of services and disservices)

- Part 2: Education example (on failures in education-systems, as reported in recent media-articles) (this post)

- Part 3: The echo-chamber (on the ‘policy-based evidence‘ loop – a key driver for failure)

- Part 4: Priority and privilege (on the impact of paediarchy and other ‘entitlement’-delusions)

- Part 5: Social example (on failures in social-policy, as reported in recent media-articles)

- Part 6: Assessment and action (on how to identify and assess disservices, and actions to remedy the fails)

In Part 1 we explored in some depth the structure of services, what services are, how they work, how they serve, and the feelings that are associated with true service. Likewise we explored how disservices are, in essence, just services that don’t deliver what they purport to do, and, again, the feelings that are associated with that failure to provide on-promise. All clear enough so far, I’d hope.

But at this point, yeah, we’re gonna need a real-life example. Several of them, probably. So let’s do that.

As we go on, we should begin to recognise the sheer scale of disservices around us – and many of them politically-explosive, in a lot of different senses. Not fun – and probably not wise to dive into straight away? So perhaps best, or wisest, to start with a relatively-innocuous example: the education-system.

Education example

What is ‘the education-system’? The usual first answer to that question would be to look at the system in terms of structure. Every country or culture does it in somewhat-different ways, or splits it into different partitions, but a typical example might be as follows:

- pre-school (optional: before 5yrs) – basic pedagogy

- primary school (mandatory: 5yrs-11yrs) – common-curriculum

- secondary school (mandatory: 11yrs-16yrs) – partitioned-curriculum

- post-secondary (mandatory/optional: 16yrs-18yrs) – specialist vocational/technical or academic

- tertiary [initial] (optional: 18yrs-21yrs) – specialist apprenticeship or bachelor-degree

- tertiary [extended] (optional: 21yrs+) – deep-specialist postgraduate academic or research

- adult (optional: 21yrs+) – vocational, professional or academic, often cross-disciplinary

From which we get pre-schools, schools, training-institutes, universities and so on. Straightforward enough.

But whilst we could derive content and building-plans and all manner of other things from this, what it doesn’t tell us anything about is why the education-system should exist. What’s the purpose of education? In a very real sense, who or what does it serve, and in what way? If we don’t know that, what’s the point of it all? And yet, worryingly, that’s a point that often seems to get missed…

If we use the generic label of ‘student’, so as to cover all age-groups and needs and so on, we could probably summarise ‘the purpose of education’ in two parts:

- develop the full potential and skills of each student – about the student as individual, as a person in their own right

- enable each student to contribute to and share within their context, to the best of their ability – about the individual in relation to the collective, contributing to and being part of a community, a company, a country, a culture or whatever

For both of these core aspects, there will always be some element of ‘same and different‘. In some ways every student is and/or needs to be the same as everyone else, or do things the same way as everyone else – we need them to learn the same languages and cultural-cues as others, in order to communicate with others and to belong to a community. And also every student is different, unique, each with their own distinct abilities, challenges, ways of seeing the world, and much, much more – which itself is part of their contribution to that community.

In short, what we’re dealing with in education – much as also in healthcare, for example – could best be described as ‘mass-uniqueness‘: everyone both same and different, both at the same time.

Which is where we need to bring in to this picture a crucial distinction between training and real-education, for which the simplest summary is this:

- training aligns with and emphasises sameness – metaphorically pushing students onto fixed trains of thought and action, on predefined tracks

- real-education (‘education’ in its literal sense) aligns with and emphasises difference – literally ‘out-leading’ each student’s unique capabilities and responses

Since by definition every student is both same-and-different, within a context that is also same-and-different, what’s required for the ‘education-system’ is actually not education alone, but an appropriate mix of training and real-education. For every student. Each of whom is, again, both same-and-different to every other student, and hence needs their own same-and-different mix of training-and-education.

In other words, decidedly fractal.

And hence tricky, to say the least… – yet that is the service-requirement here.

Which means, in turn, that any ‘education-service’ that fails to deliver to that requirement for ‘same-and-different’ is likely to deliver some degree of disservice to at least some of the stakeholders in the service-context.

In short, the inherent risks of disservice in a conventional-style ‘education-service’ are pretty high, even before we start. Which means that, as architects for a service, we need to pay very conscious attention to those risks – otherwise we’re likely to find a lot of people getting decidedly upset, without necessarily knowing why they’re getting upset. Not fun…

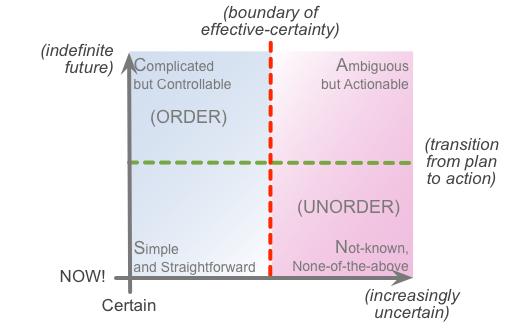

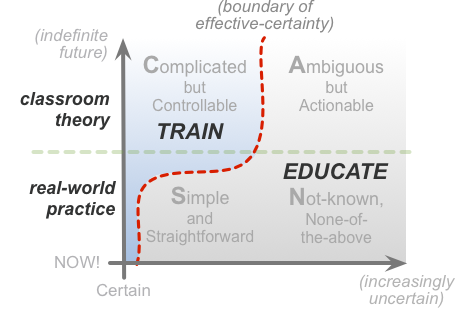

Just to make this even more complex, there’s another crucial distinction here between theory and practice – between what seems to work in the classroom or the lab, versus what actually works out there in the unordered ‘messiness’ and real-time pressures of the real-world. For example, if we think of this in terms of the SCAN framework:

What we note in practice is all too many illustrations of Yogi Berra’s adage that “In theory there’s no difference between theory and practice; in practice, there is!” – where the assumptions inherent in all training don’t work as well in the real-world as they purportedly do in theory, and hence that real-education is needed to cover the gaps and inherent-uncertainties in the rest of the context. What we get from that is a SCAN crossmap that looks somewhat like this:

Which again leads to another paired set of emphases:

- training emphasises content – is ‘content-first’, content applied to context

- real-education emphasises context – is ‘context-first’, content derived from context

The development of skill follows a related pattern, starting with an emphasis on step-by-step training at the start, but requiring increasing levels of real-education, self-education, self-awareness and self-assessment, as competence in the respective skill develops onward from trainee to apprentice to journeyman to master:

We could also note a crucial difference in regard to tests and testing:

- training emphasises true/false tests – compliance or non-compliance to the assertions of the training-content, relative to an external standard

- real-education emphasises qualitative tests – better/worse or good/not-so-good, often relative to a personal standard

From a service-provision perspective, the advantage of training is that it’s efficient, and predictable: we teach the same material to every student in the same way, with the same predefined content applied to the same predefined types of context. It’s also what we need when each student must work the same way, and/or arrive at the same results or actions, such as with laws of mid-range physics or chemistry, or core cultural requirements such as language and social-norms. And because it’s content-first, with compliance to content a key concern, it’s also (relatively) easy and (relatively) cheap to teach, and to test, via rote-learning, tick-the-box tests and so on.

The hidden disadvantage of training is that, because it’s ‘content-first’, it will inherently tend to create cognitive-bias, in which the real-world context is filtered and misinterpreted in terms of the predefined content, leading to ‘policy-based evidence‘, circular-reasoning and all manner of other real-world problems. Countering that risk is one of the reasons why true ‘context-first’ education is so important, especially in skills-development – including social-skills.

The advantages of real-education (i.e. education in the literal sense of ‘out-leading’) tend to be somewhat hidden, whilst its disadvantages are often all-too-visible. For a start, real-education is neither easy nor cheap, in almost any sense – a fact which brings tears to the eyes and tears to the heart of many an administrator. Perhaps worse, for many stakeholders, many of the outcomes of real-education are inherently unpredictable – a point that can be near-anathema for those who, for any reason, need to hold to some notion of a predictable, controllable, ever-certain future.

In short, training and its simplistic ‘certification‘ may be very popular amongst many of the stakeholders of the ‘education-system’; but the inherent-uncertainties of the outcomes and even the existence of real-education can be very unpopular indeed. All of which, without proper understanding of how education actually works, can set the stage for an awful lot of disservices…

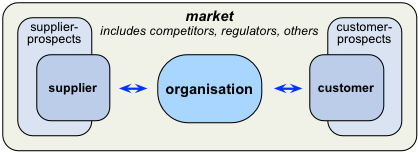

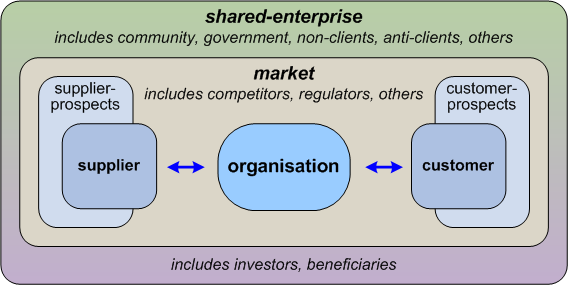

The next question would be to ask about who are the stakeholders for the ‘education-system’ – because the enterprise here is a lot more complex than that of a simple supply-chain. That point should become clear as soon as we ask the question “Who is the customer?” – is it the students, the parents, potential employers, local community, local-government, national- or federal-government, taxpayers, who? In short, for any service-provider in this space, we’re not likely to be dealing with a service-context that’s as simple as this:

Or even like this:

But inherently something more more like this:

And note that each service-provider is always in context of every stakeholder in the respective shared-enterprise. Which in effect also means that every service-provider must provide appropriate services for every stakeholder in that shared-enterprise. In many cases the respective services may span only the outer elements of the service-cycle, and may be either explicit or implicit – but they’re an inherent requirement of service itself, and they always exist in some form or other, whether we’re aware of them or not. Which, if we’re not aware of them, as service-architects and service-designers, leaves plenty of scope for serious disservices…

So let’s list out some of the players in the ‘education-system’ shared-enterprise, and their likely roles, needs and drivers:

- students – want, need or required to develop competences etc, as per the earlier ‘The purpose of education’; later-stage students may also invest, or be required to invest, financially or otherwise, as ‘customers’ or service-consumers of the respective service-provision, in expectation of future competence, financial-return, status and/or other more social forms of recompense

- teachers, lecturers, instructors and content-providers of automated ‘education-systems’ – prepare and deliver training-content and/or real-education context for students, typically in return for pay and/or status, or other more social forms of recompense

- administrators – manage scheduling, costs etc, typically in return for pay and/or status etc

- examiners, testers and content/test-providers of automated ‘education-test systems’ – prepare and deliver test-services for students, aligned to prior training and/or education, typically in return for pay and/or status etc

- auditors and inspectors of education service-providers – verify quality and compliance of education-services, typically on behalf of other bodies (government, professional, academic, investors etc), and typically in return for pay and/or status etc

- parents and similar familially- and/or socially-related ‘concerned parties’ – provide personal, financial and other support to the student, typically in expectation of familial and/or social returns

- employers, later-stage education service-providers and similar ‘concerned parties’ – may provide personal, financial and other support to the student (post-secondary, tertiary or adult), typically in expectation of enhanced-capability returns

- social-investors, including taxpayers etc – provide financial and other investment to the service-provider and/or student, typically in expectation of social returns

- financial-investors – provide financial investment to the service-provider, typically in expectation of financial returns

- broader community – provide social support and social ‘licence to operate’ for students and/or service-providers, typically in expectation of broader social gains and/or compliance to and support of social/cultural norms

To assess service-provision for each of these stakeholders, and for all stakeholders collectively, we need to compare every action (and, for that matter, inaction) against the overall enterprise-purpose, namely to develop the full potential and skills of each student, and to enable each student to contribute to and share within their context, to the best of their ability. The straightforward test here is that:

- the outcome will be true-service to the extent that actions and inactions do align with that overall shared-purpose, across all stakeholders and stakeholder-groups;

- the outcome will be disservice to the extent that actions and inactions do not align with that purpose, but instead service the needs of a single stakeholder, stakeholder-group or subset of stakeholders and stakeholder-groups across the overall shared-enterprise.

So how does this work in practice? One concern that we might explore would be the current mix of training versus real-education throughout the end-to-end service-provision of the overall ‘education-system’:

- pre-school – some training, but mostly real-education, helping each student find and express more of who they are

- primary school – training-element gradually increasing, to near-dominance as predefined ‘common curriculum’ by the end of the primary-school stage

- secondary school – primarily training (‘teach to the exam’), with real-education elements either prominent or even present only in specific subject-areas and electives

- post-secondary – primarily training (‘teach to the exam’) for vocational/technical or academic

- initial tertiary – a more even mix of training and real-education, in order to push skills-development, but in the specific subject-area only

- extended tertiary – training mostly assumed complete, hence much stronger emphasis on real-education, but in the specific subject-area only

- adult – contextual mix of training and real-education, depending on the need and current maturity-level (vocational, professional and/or academic)

In short, as we move further into the overall ‘education-system’, true/false ‘fact’-based training is ramped up more and more, with real-education – especially real-education in relation to anything other than a specific selected subject-area – increasingly either abandoned or, in some cases, even actively suppressed. (The reasons for the latter are varied, but the most common is the purported need to ‘teach to the exam’, which itself is typically based on a true/false training-type model.) We also see an increasing emphasis on narrow-focus specialism, all the way to the end of extended-tertiary – only at the post-tertiary ‘adult’-level does the possibility of cross-disciplinary study become as common as it was in the pre-school years. The result is that by the time students leave school, their critical-thinking and self-assessment skills, and abilities to make sense of whole-as-whole, may not have been developed much beyond those of a six- or seven-year-old – perhaps particularly in social contexts, but more generally as well.

Okay, there may be certain stakeholders who might consider the suppression of holism-awareness and critical-thinking skills to be a benefit rather than a drawback. Ideologues of any kind would be likely to feel that way, for example, as it means that their chosen ideology could not be doubted or questioned, regardless of how much damage the ideology itself might cause for the broader culture. Likewise for the supposed beneficiaries of ‘divide-and-rule’: an inability to see whole-as-whole makes awkward questions and comparisons less likely. But for most practical contexts, such as employability and the like, a lack of capability for self-education and self-development of skills and so on soon becomes a huge problem for almost everyone – especially in a world where robotic step-by-step tasks can increasingly be carried out by literal robots at much lower cost and complexity.

This imbalance between training and real-education also means that the student may have serious difficulties catching up again when the studies do require such skills, such as WIB Beveridge indicates in his classic The Art of Scientific Investigation:

Elaborate apparatus plays an important part in the science of today, but I sometimes wonder if we are not inclined to forget that the most important instrument in research must always be the mind of [the researcher]. It is true that much time and effort is devoted to training and equipping the scientist’s mind, but little attention is paid to the technicalities of making the best use of it.

In an all too literal sense, a schools-‘education’ that in effect suppresses essential life-skills and, for later life, research-skills – the ability to work with real-world uncertainty, rather than pretend that it doesn’t exist – is doing everyone a serious disservice. It’s certainly not helping, anyway.

Which means that, from a service-architecture perspective, it’s something that we do need to review and reassess, to bring it closer towards the purported purpose of education and the education-system.

Another key point for which we need to watch carefully is the balance between all of the different stakeholders. For example, what happens when one or other of the stakeholder-groups asserts or imposes its priority over the others? To see some of the effects and outcomes, let’s look at examples reported recently in the media:

— Media example #1: BBC: ‘CBI head calls for GCSEs to be scrapped’

This needs perhaps a bit of explanation, as it’s somewhat a Britain-specific example. ‘CBI’ is ‘Council for British Industry’, probably the most influential employers’-organisation in Britain; and ‘GCSE’ is ‘General Certificate of Secondary Education’, the standard exam-series for the end of secondary-school, at around age 16. To quote the BBC article:

The head of the CBI says a date must be set in the next five years to scrap GCSEs and introduce an exam system with equal status for vocational subjects.

John Cridland, director general of the employers’ group, says England’s exam system is narrow and out of date.

He proposes a system in which the most important exams would be A-levels, including both academic and vocational subjects, taken at the age of 18.

He says that for too long “we’ve just pretended” to have an exam system that values vocational education, when in practice, exams have operated as stepping stones towards a university degree.

And he adds:

“Non-academic routes should be rigorous and different to academic ones, but not second best.”

The lack of a strong vocational education at the moment means that many pupils are poorly served, he says, as not all children are suited to a narrowly academic approach.

In effect, he’s saying that the current secondary-schools ‘education’-system is structurally doing a disservice to any student whose expected career does not centre around an academic-style path – and in the process, also doing a disservice to business’ needs for appropriately-skilled staff.

But where does this skew towards academia come from? There’ll no doubt be plenty of factors, but one of them at least will be that teachers themselves go through that career-path, and hence, through cognitive-bias, will naturally tend to over-emphasise the importance of their paradigm and worldview. And another factor, rather deeper-rooted and harder to challenge, is the nineteenth-century British class-system, and its later resurgence and reflection under the guise of Taylorism – the deep-myth of ‘the elite’.

The fundamental principle of the class-system was that the aristocracy own everything, and purport to have the ‘right’ to control and direct all others’ lives, for the aristocracy’s benefit. This was expressed, for example, in the distinction between ‘public-schools’, which were largely reserved for the children of the aristocracy, and other ‘lesser’ schools – where they existed at all – for everyone else.

(Note for Americans and others: In Britain a so-called ‘public school’ is, confusingly, what would elsewhere be called a ‘private school’, often with high fees that effectively limit it solely to the families of the wealthy. The ‘public’ label arose because such schools were expected to be the training-grounds for ‘public servants’, the administrators and army-officers of the Empire – kind of a proto-MBA, one could say? In some ways the same ‘public servant’ label does still fit, given the predominance of Old Etonians and the like in British government and elsewhere: but whom they really serve, and whether this is actually to the nation’s real benefit, is an assertion that some would doubt…)

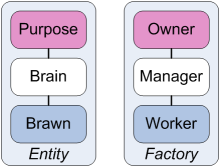

By the late nineteenth-century, this social-split had morphed somewhat into the current Taylorist model, with its distinct boundaries between ‘owners’, ‘managers’, and ‘workers’:

As far as the wider range of schools are concerned, the ‘owners’ and their children are still almost literally a class to themselves. Which, for the rest, leaves the remainder of the Taylorist split: managers who think, and don’t do; and workers who do, and don’t (or ‘shouldn’t’) think.

Which leads, in turn, to the over-emphasis on the academic-style paradigm, as the supposedly only-available means of ‘upward social mobility’ for children in general – because ‘academic’ is equated with ‘think’, which in turn is equated with ‘manager’, which in turn is equated with ‘socially-better’.

And that notion of ‘better’ is in turn based somewhat on a crucial social-delusion, that ‘power’ is not ‘the ability to do work’ (as in physics and the like), but somehow ‘the ability to avoid work’ – or the ‘right’ to entrap others into doing your work for you.

Which is a pretty serious social-disservice… – and probably not a wise one for schools to promote, though we see it all too often in notions such as certain schools claiming that their students are ‘the elite’ solely on the basis of the school’s excessive academic bias.

In Britain, a near-permanent split between ‘academic’ and ‘non-academic’ streams takes place as the result of an exam at the end of primary-school. Back when I was a kid, the exam was known as the ’11-Plus’, and was considered by perhaps too many to divide the students into the ‘successes’ who went to the High Schools or Grammar Schools to follow the academic stream to university and managerhood, versus the ‘failures’ who were sent to the Secondary Modern schools, or later, the Comprehensives, and were deemed destined only for near-servitude as secretaries, salesmen and shop-assistants.

(As it happens, I was one those who was categorised as a ‘success’, and went on to grammar-school and the like. But I certainly didn’t feel a ‘success’ back then, and I still don’t now. So much for other people’s arbitrary labels…)

But in some towns – and ours was one of them – there was a third option: the Technical High School. These were secondary-schools that focussed on vocational training and education – in effect, developing the students into a much more valid ‘elite’ of the trades, aiming towards apprenticeship and beyond. The attitude there was not this debilitating and skewed categorisation into ‘successes’ and ‘failures’, but instead something much more real and honest: “the 11-Plus shows that the academic-style is not your strength – so let’s find out what your strength is, and help you develop it”.

It’s that third way that fits most strongly with what John Cridland describes above – and yet these days the route to there is all but blocked by that otherwise-bizarre obsession with the belief that “academic is best for everyone”. The blunt fact is that, for many if not most students, the academic path is not best for them – and the respective education-services need urgently to change to better reflect that fact, to avoid doing lifelong disservice to probably the majority of school-students and the broader socioeconomic communities beyond.

Which brings us to:

— Media example #2: BBC: ‘Ofsted purges 1,200 ‘not good enough’ inspectors‘

In Britain, Ofsted is the government-funded body that’s tasked with monitoring quality of education delivered by schools, and ensuring compliance to government expectations and government standards. As one might expect, it’s become a classic example of a political-football, with standards and requirements almost randomly changing with each change of government. In line with the ideology of the current government, it’s also largely outsourced – leading to governance-problems in its own right, as well as those it creates for the often-unwilling recipients of its services.

It’s infamous for its Taylorist-style approach to ‘quality’, with classic systemic flaws such as arbitrary numeric targets (critiqued in inimitable fashion, though for a different context, in Simon Guilfoyle’s post ‘Spot the difference‘) and ‘league-tables’ that somehow assume that the same criteria will always apply to inherently-‘same-and-different’ schools and contexts. In short, an all-but-guaranteed disservice. (Not entirely their fault, of course, since these absurdities are forced upon them by government-policy.)

What this example adds is the implication that not only were the test-methods not up to scratch, but neither, apparently, were many of the testers:

National Association of Head Teachers general secretary Russell Hobby said: “You look back and say, for the last few years we’ve been inspected by a group where 40% weren’t up to the job.

“If people could say, ‘It’s tough but fair,’ then fine, but it was tough and unfair and tackling that should have been a priority.”

The head of Ofsted replied that:

“We stand by the inspections that we have done in the last few years.

“The teaching profession is always being asked to improve and reform, and Ofsted is no different.

“We see an opportunity to improve our services and we are going to take it.”

And added that “that this move should not be seen as an admission that [Ofsted’s] inspections were substandard”. No surprise, though, that the teaching-profession sees it otherwise:

Dr Mary Bousted, general secretary of the Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL), said: “It is unacceptable that these inspectors have been judging school quality – and coming to conclusions which, too often, lack validity or reliability.

“Ofsted is consistently behind the curve – tinkering with an inspection system which is no longer fit for purpose. As the CBI today argues, we need radical reform of inspection to enable the development of innovation and creativity in our schools.”

Which links back to Media Example #1 above – but focussing solely on the inspection-regime, rather than on what schools themselves might need to do to bring their services more into line with the CBI’s suggestions. Which is another characteristic of disservices that we see all-too-often: that the responsibility for fixing disservices is always made out to be Somebody Else’s Problem…

Continuing on with the theme of inspection of quality of education, this brings us to:

— Media example #3: BBC: ‘University inspections face major overhaul‘

This is similar to the Ofsted example above, but with a different review-body:

The plans aim to create a way of ensuring quality at a time of increasing consumer pressure from students and doubts about standards in some new private providers.

An annual survey published this month by the Higher Education Policy Institute showed that less than half of students believed they had had good or very good value for money from their courses.

The shake-up is expected to propose different levels of supervision for different parts of the higher education sector. Universities are said to be resistant to a “one-size-fits-all” monitoring system.

That last point is probably wise, given that crucial concern we saw earlier above around ‘same-and-different’. Yet the same Taylorist-style error, about trying to directly-compare things that are inherently not alike, again rears up in another part of the proposals, with apparently-unexamined political-ideology again the driver:

…the plans are expected to “embed” the idea of a way of measuring the quality of teaching in universities. The Conservatives’ election manifesto promised a way of comparing university teaching standards as well as research.

And likewise similar ideology applied to the management and governance of the inspection-regime itself:

Last October, a public tendering process was announced to run the university inspection system from 2017. But it now seems that it is going to be a different kind of system from the one currently operated by the QAA.

The proposed changes are also likely to raise questions about the independence of a regulatory system that no longer has regular external checks.

Yet there’s also another twist, around claimed ‘priority’ for some stakeholders relative to others:

There are questions about whether there will in effect be a two-tier system – with a more light-touch approach for established universities and more robust scrutiny for those outside this group.

All of which indicates that there’s a real mess of disservices going on in this space – some of them overtly ‘political’, others maybe even outright intentional. All of which constrains and limits and maybe even damages the real shared-enterprise aims for education – summarised earlier above as “develop the full potential and skills of each student”, and “enable each student to contribute to and share within their context, to the best of their ability”. And ultimately those who probably suffer the most from those disservices are the students themselves:

The questions about how university standards are monitored come as students are being increasingly voluble about challenging the quality of their courses.

The increase in tuition fees has brought into sharper focus value-for-money questions about teaching standards, contact hours and how degree standards compare between different institutions.

Which brings us to:

— Media example #4: BBC: ‘Four in 10 students say university not good value – survey’

Here in Britain, there’s been a major change in how university-courses are funded. Previously, all courses were state-funded, but some years back the government changed this, such that students now have to pay some or all of their tuition costs. As this BBC article states, “When tuition fees were trebled to £9,000 in 2012, the fundamental relationship between the student and their university changed” – and with that change in relationship has come a significant difference in students’ service-expectations and levels of service-satisfaction. Before the change:

Universities UK said the last national student survey found 86% of students were satisfied with their course.

Whereas after the change:

Four in 10 of the first students to pay higher fees do not believe their courses have been good value for money, a survey for BBC Radio 5 live suggests.

Just over half say their university course has been good value and about 8% are undecided.

We can also see some of the metrics and drivers that influenced satisfaction (or not) with the service-as-delivered:

The survey found there were differences of opinion between students doing different types of courses.

Two-thirds of those studying science, technology, maths and engineering [STEM] – subjects that require a lot of practical teaching and staff time – said their courses had been good value.

And 44% of humanities and social science students, which tend to receive less direct teaching time, said they felt their courses represented good value.

Some 58% felt their courses had left them at least somewhat prepared for the future.

It’s instructive to turn those figures round: that around one-third of the STEM students felt that their course had not been good value; more than half of humanities and arts courses said the same about their courses; and over 40% felt that their courses had left them unprepared for their future. Okay, the whole concept of ‘value for money’ is inherently flawed and inherently problematic, and confusions around price, value, worth and cost merely add to the mess – but either way, that’s a lot of dissatisfaction, a lot of disservice…

Perhaps more subtly, but in a way that also links back to ‘Media Example #1′ earlier above, the shift towards student-funded courses is also distorting students’ choices for study:

Mr Hillman also noted that as fees went up, students were tending to choose subjects “more obviously linked to jobs”.

And whilst it’s probably true that “Degree holders also continue to earn considerably more than non-graduates over a working lifetime and employers are predicting a double-digit rise in graduate vacancies this year”, the new monetary pressure does force the students to focus on their future far more in monetary terms – towards a more-active engagement in the money-economy (rather than, say, the social-care economy, or the sharing-economy) – than they might otherwise desire or choose.

In both senses, that distortion of choice and capability represents, to at least some degree, a disservice relative to both sides of the education-system’s purpose: the skills and development of the student as an individual, and in terms of the natural contribution towards the society and its needs. The money-economy and its ‘owners’ might well benefit from such a distortion – but it’s questionable as to whether the same might be said for the students, or for society in general.

Practical implications for enterprise-architecture

What we should be able to see from all of the above is that misservices and disservices are disturbingly common: so much so that for many people in education and elsewhere, a sense of having received ‘good service’, in terms of the purpose for the shared-enterprise, is experienced as more the exception than the norm. Each of those media-examples above illustrated that point all too well.

And every disservice represents a risk to the service-providers within that shared-enterprise: either as a direct-risk in terms of value-flow and the like, an indirect-risk in terms of shared-enterprise themes such as ‘social licence to operate‘, or a more-subtle kurtosis-risk that can build and build in the background and then suddenly explode without warning.

Which, if we’re working as enterprise-architects or service-architects in that context, is likely to be kinda important to us…

As indicated in the previous post in this series, there are probably an almost infinite number of ways in which an intended service can end up delivering a disservice to one or more stakeholders or stakeholder-groups: if we try to define them all, we’d soon find ourselves drowning in too much detail, to be able to do anything useful about it at all. Which is what usually happens, which is why the problems just get shoved into the ‘too-hard’ basket, which is why so many otherwise good services stutter and fail into a near-unmanageable mess of disservices. Nothing we can do about it. Oh well.

Yet there is a way out of that fatalism and futility – that’s to realise that, beyond unavoidable breakdowns and the like, there are just two common causes for any kind of disservice. So if we can learn to watch for those two causes, and design our way around them, most of our disservices could potentially disappear at a stroke.

(That’s the theory, anyway: the practice can be more than a bit more tricky, of course, as we’ll soon discover! But the point is that it can be done – we don’t and shouldn’t need to pretend that it can’t.)

The first of these core causes is one that we’d alluded to earlier above: cognitive-bias, particularly in a form I describe as ‘the echo-chamber’. We’ll explore that in Part 3 of this series.

The other core cause is that some stakeholders attempt to assert or impose priority and privilege above all others – or, more specifically, some form of priority or privilege over others that is unwarranted in terms of the overall purpose for the shared-enterprise. Those assertions are often backed up by some decidedly-dysfunctional tactics that we really ought to describe as abuse, or even as violence. More on that in Part 4 of this series.

Those types of causes of disservice can often coincide or interact. This occurs perhaps especially in any context that is highly emotive and/or highly ‘political’ – of which a classic example is social-policy. We’ll explore some examples of this in Part 5 of this series.

And finally, in Part 6 of this series, we’ll outline a practical ‘how-to’ for enterprise-architects and others – checklists, frameworks, practices and processes to help us identify potential disservices, and design means to mitigate them before they can cause harm to the overall enterprise.

Enough for now on this set of examples: time to move on to more of the practical detail.

Unless you have any comments so far, of course?

Tom, I hope you don’t mind if I add this material to your exploration of the services and disservices of education. I expect you can remove it if you feel it distracts from what you’re trying to do. I’m a Godin fan, myself, and I think this is important work: http://sethgodin.typepad.com/files/stop-stealing-dreams-print.pdf

I do apologize for the USA context.

Many thanks for this, Doug – it’s important. (And yeah, I’m definitely a Seth Godin fan too. 🙂 )

Please, no need to “apologize for the US content” – sure, some of the details are US-specific, but in broad-brush terms it’s much the same in Britain and Australia at least: kind of a globally-shared stuff-up, in too many ways. Oh well…

For another nominally-US-but-all-too-applicable-elsewhere critique, there’s Postman and Weingartner’s 1969 classic ‘Teaching as a subversive activity‘ [PDF] – reading it now, almost 50 years later, and still there’s painfully little improvement… (Likewise for Paul Goodman’s ‘Compulsory Miseducation‘, which really is 50 years ago now…)

Even within the stakeholders you listed, there are different groups. Both students and parents can be partitioned into the engaged, the neutral, and the disengaged. Education is probably the best example of the ‘same and different’ issue given the different permutations of stakeholders and how utterly treating everyone the same has failed.

Yep. Not much else needs to be said to that last point, sadly….

(Other than that we really really really need to find a way to sort out that miserable mess before it destroys yet another generation’s lives… 🙁 )

Really interesting series as always, I’m curious where it will lead to 🙂

Anyway one small comment to the example you give here, especially to the mix of real-education vs. training in schools: I believe that schools are actually not the only “education service providers”, there are at least also parents who should provide the service. I also believe that parents are better equiped to give real-education than training. So when you sum up the service provided by schools and the service provided by parents you get much balanced view.

Thanks, Ondra – yes, strong agree that the real ‘education-system’ is much broader than that which most people – perhaps particularly politicians and administrators – seem to see as ‘the system’. This does seem to be fully recognised by teachers at pre- and primary-school level, but seems to be all but forgotten by the time of secondary-school – in fact most parents are more like actively shut-out from their children’s schooling, rather than included – other than for purposes of blame when their ‘fails’ at something, that is…

“I also believe that parents are better equipped to give real-education than training.”

Yes, probably so – though kind of an indictment on the system-design, that the people who purport to be the professionals at this are not “better equipped” to do it, whereas the nominal-amateurs are?

“So when you sum up the service provided by schools and the service provided by parents you get much balanced view.”

Agreed. It then becomes an interesting question, though, as to what exactly it is that parents are paying for… – and, in this insane economics, whether the culture as a whole should be paying parents to provide those real-education services? 🙂

Just a quick response (as I don’t want to distract you from the core of the series with discussing only one partial example :)) – by “better equipped” I also meant the conditions under which parents provide the “service”, this is that they educate just a few children that they know very well. Those conditions are much more suitable for the “unique” side of the “mass-unique” education requirement…

(just not to make wrong impression: I don’t mean it as an apology for teachers, I just try to point out that it is more complex:)

To your last question: I believe that it should 🙂 And I guess it is quite in line with your statement (in mythquakes series or in RBPEA or somewhere) that raising children or more generally motherhood should of course be considered as work:)

PS: and sorry for my English, I wasn’t trained enough in it 🙂

Hey Tom — As a known advocate for the death of the concept of money, it is somewhat startling to hear you say:

“what exactly it is that parents are paying for”

and

“the culture as a whole should be paying parents”

I know this is a tangent for this particular series of writings, but maybe we can come back to the question of what it means to “pay” for education under any circumstances?

Did I just “pass the hand grenade”? (Trying to learn your language as we go 🙂 )

Okay, Doug, nice catch! 🙂

Shortish-answer to first question: In an (at-present) somewhat-idealised and, for the most part, definitely future economics, we would (and, I would argue, must) expunge the concept of money and ‘quid-pro-quo’ exchanges, what I sometimes describe as ‘double-entry life-keeping’. At the present time, though, the economics definitely does run as a money-based possession-economy – and I’m realist enough to acknowledge that fact, especially as we’re describing disservices in the present (‘as-is’) rather than future (‘to-be’).

At some point, yeah, we need to greatly expand the concept of ‘pay’, or even (and preferably?) reframe it entirely: yet right now we do have to work with what we have. Whether we like it or not… 😐

On “Did I just “pass the hand grenade”?” – short answer is no, not really: your question is entirely valid, and one I did need to respond to, as per above, but it isn’t ‘pass the grenade’ in the sense that’s referenced in the post above. There, ‘pass the grenade’ refers to an industry-wide kurtosis-risk in which there’s an ‘everybody’s doing it, so obviously it doesn’t matter’ attitude to some major disservice that is being done to various other stakeholders: airlines’ and telcos’ infamously-poor ‘customer-service’ is a classic example. When the kurtosis-risk does eventuate for one of the industry-players, that player often incurs all of the rage that would otherwise be addressed to other players in the same industry – the ‘United Breaks Guitars’ incident was a classic example of this, where United ended up ‘wearing’ all of the anger about others airlines’ equally-poor service. The tragedy is that the rest of the industry carries right on delivering the same disservices, because it was Somebody Else, rather than them, who took the damage. I call this ‘pass the grenade’ because it’s as dangerous as Russian Roulette but without the visibility of the danger, and because it’s like ‘pass the hot-potato’ but without the immediacy of the warning-pain.

Thanks!