RBPEA: Why imagine a world beyond money

In the previous two posts in this series on background behind futures for enterprise-architecture (see video), we explored the idea of a focus on value, rather than money, as the anchor for our architectures; and then set out to imagine a world beyond money. But why? What’s the value in doing this?

One of the core concerns of enterprise-architecture and the like is about management of resources, particularly at larger scale and over longer periods of time. Another core concern is about guidance of change, often across the entire scope of an enterprise. For these and other concerns, probably our most common concept is to describe everything in monetary terms: price, cost, budgets and the like. In business-architecture, the money – where it comes from, where it goes – is often almost the only thing we’d be expected to think about. Money as the main metric for everything; money as the main means for managing resources.

Yet how well does it actually work, to satisfy all of those needs?

In those previous two posts we saw that money doesn’t work well as ‘the metric for everything’, the sole measure of value: as we saw, there are too many important things that get hidden from view if we focus only on money. So maybe the same might apply to the money-system itself, as a means for managing resources? Maybe there are some hidden assumptions there that we might need to bring to the surface?

In which case, let’s explore this with another practical experiment…

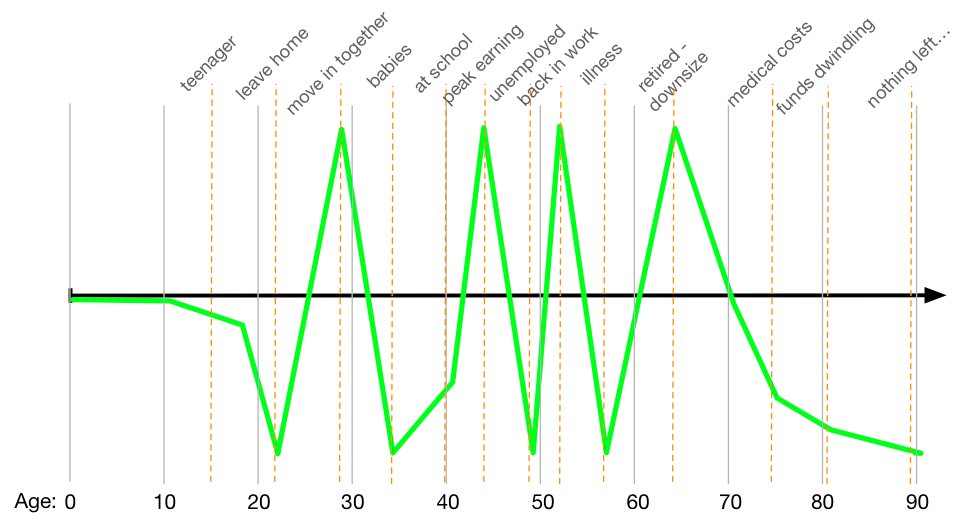

First, let’s imagine the key steps in the stereotypic human life-sequence – from child or teenager still living at home, to first leaving home, to moving in with a partner, to having kids, the kids at school, the kids themselves leaving home, and onward to retirement and old age.

(This experiment often works better if we make this personal: so imagine that this is you we’re describing here – your own history so far, and your expectations for the future.)

Given that, let’s apply that test of ‘What do you need?‘: what were, are or would be the resource-needs that you or others have, for each stage in that life-sequence?

For example, as a teenager, most of your needs would have been met by someone else – your parents, most usually. (Note we’re talking about needs here, not wants – the wants of a teenager are often limitless!)

So when you first leave home, what are your needs then? What are the changes? For most people, it’s probable that your needs would suddenly skyrocket: you’d need somewhere to live, the deposit for the rent, and the furniture and bedding and kitchenware and all the other sheer stuff that makes a household work.

What happens when first you move in with a partner? What are the changes at this stage? For most, it’s probable that your needs would plummet, as you not only gain economies of scale – two for the price of one, for a lot of things – but you probably too much of everything from when you each lived on your own.

Keep walking through that life-sequence: what happens when babies start to arrive? When the children go to school? On and on through the whole of that sequence… And perhaps throw in a few periods of illness or unemployment along the way, just to add a bit more detail. What are your needs, at each stage?

Once you’ve explored that sequence, map it out as a simple graph, with age in years as the x-axis, and level of needs, from low to high, as the y-axis. (If you prefer, map the y-axis in terms of expenditure, of monetary outlay to satisfy those needs – in our money-based economics, it comes to much the same thing.)

My guess is that your graph will look something like this, with wild swings from one extreme to the other:

For the next part of the experiment, describe or imagine the actual or probable resource-availability for each stage in that same life-sequence – teenager, first leaving home, moving in with a partner, and so on. Again, perhaps add a few periods of illness or unemployment along the way, to make it a richer picture.

The simplest way to do this is to map it out in terms of monetary income – what pay or other income you have, at each stage. Model this as your own household-income, you as an individual, as a couple, as your own immediate family: keep others out of the picture at present.

Once you’ve explored that life-sequence in terms of likely resource-availability, map the result out in the same way as for the previous graph. Again use age-in-years as the x-axis, but this time, rather than resource-needs or expenditure as the y-axis, show resource-availability or income.

My guess is that this time your graph will look something like this:

Again, a lot of wild swings there, often from extreme to extreme.

For the final step in this exercise, compare resource-needs to resource-availability throughout that stereotypic life-sequence. The simplest way to do this is to put the two graphs together – a combined graph, with a red trend-line representing typical resource-needs at each point in the life-sequence, and a green trend-line representing typical resource-availability at the same points in that sequence. Hence if we combine those two example graphs above, what we’d get is this:

Yeah – it’s an almost perfect mismatch. Whenever we least need resources, we’re most likely to have them; and whenever we most need resources, we’re least likely to have them. To put it another way, what this shows us is that the natural tendency – the ‘gravity’ – of our entire economy is to move resources to wherever they’re least needed.

As a means of managing shared resources, it’s not merely a poor system – it’s arguably the worst system that we could possibly devise. And yet that’s the inherent nature of the system that we live in at present, day after day, year after year, for all of our lives.

Ouch…

To make our economics at least seem to sort-of work, we need to counter that natural-gravity of the system. Hence the huge infrastructure of banking, insurance, tax and more, to try to move resources around to when and where they’re actually needed. Hence also money itself, as a sort-of standardised means to measure, monitor and manage that time-shifting of resource-needs and resource-availability. Yet that infrastructure is colossally expensive: put all together, it already accounts for around half of all ‘economic-effort’, and still rising fast. All of it dangerously fragile, wide-open to all manner of misuses. And all of it is colossally inefficient, given that all of its effort is pushing against the natural-gravity of the entire system.

In short, as a means for managing our shared resources, our current money-based economics doesn’t work. Not well. Not for most people. Probably not for anyone, in the longer run.

Ouch…

We definitely need to do better than this.

Which is why we need to imagine a world beyond money.

The next question, of course, is how.

Which is where enterprise-architecture comes back into the picture…

Implications for enterprise-architecture

We’ve seen in the previous posts that we can imagine a world beyond money.

We’ve seen here why we’d need a world beyond money.

The next question is how we could build a world without money. Or, from our perspective, the architectures for a world beyond money.

Which, for most of us, might seem an impossible task. Way out of scope for anything we might do.

Actually, no.

Because money isn’t actually the real problem here. Nor is the money-system, or anything built upon it.

It’s not even anyone’s fault: there’s no evil ‘Them’ to blame here.

It’s just us. All of us, doing what we do. But doing what we do, in context of a bunch of unquestioned myths about ‘how the world really works’.

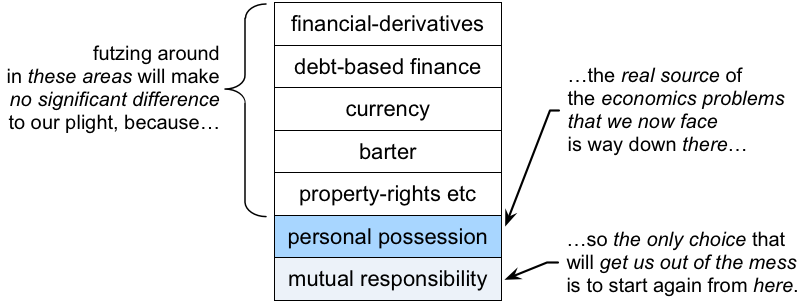

Hence as architects, the one most useful thing right now that we can do about this is to worry less about what’s happening on the surface, and instead start to explore the hidden assumptions behind those myths.

The catch is that the myths we most need to explore and resolve are a lot further down than we might expect:do echo out into every part of every architecture are a lot further down than we might expect:

Yet the effects of those unexamined myths do echo out into even the most IT-centric of ‘enterprise’-architectures – so even up there at the surface levels, the outcomes of those deep-level explorations can deliver huge benefits to the efficiency and effectiveness of our everyday architectures. Hence, again, this matters for our work.

As in the graphic just above, the key emphasis around concepts of ownership – in particular, the crucial distinctions between possession, versus responsibility or stewardship. For example, it doesn’t take much exploration to recognise that there’s no way to make a possession-based economics sustainable in the longer-term – whereas a responsibility-based economics can be made sustainable indefinitely. And again, getting clear on what works and what doesn’t at larger scales can provide real value to the architectures we build for our organisations.

But where do we start? How do we find the ‘How‘?

One worthwhile place, perhaps, is with what we’d explored in the previous two posts: that concept of value, from the ‘A taste for value’ post, and that key question of “What do you need?”, from the post on ‘Imagine a world beyond money’. And apply all of that, to look at ‘the economy’ as a whole.

So let’s do that, in the next and final post in this series. See you there!

Leave a Reply