Questions on belief

“What do you believe?” “How do you know that you believe? “How can you prove that you believe that?” What…?

Okay, yes, I probably made a mistake, being so foolish as to publish a video in the Tetradian on Change series on YouTube, about ‘Religion is a private matter‘, and the implications of that point in contexts of change.

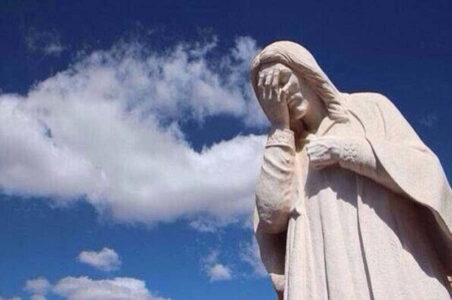

Because boy oh boy, did it trigger off some, uh, interesting responses on LinkedIn… Fair enough, some sensible comments too – even wise comments, some of them. Yet too many were so far up into face-palm territory that I really do need put up this graphic again:

Sealioning and more, some of it, too. Oh boy, what fun. So yeah, I found myself straight back in the ‘grumpy old guy’ state, from back about two years ago – see ‘Intimations of arrogance from a grumpy old guy?‘ and ‘Intimations of arrogance – an addendum‘ for more on that. Bah.

For example, one of the commenters came up with the phrase “I care about you”, followed by this, uh, trivial little list of questions:

- What is fact?

- What is belief?

- What is religion?

- Who determines what is a fact?

- Can you arrive at facts without belief?

- What is a private matter?

- Who determines what should be a private manner?

- What does it mean to impose?

- What does it mean to punish others?

- What is social unrest and social damage?

- Who determines what is social unrest and social damage?

- Why should we minimize social unrest and social damage?

- Who determines what we should and shouldn’t do?

- To what end and why?

- Is this your belief?

- How do you know?

Yet although I now definitely doubt that those questions were asked in good faith, they arguably are worth exploring – so these were my responses on LinkedIn:

– “What is fact?” – literally, ‘a making’, ‘that which is made’. In practice, that which stays the same regardless of belief. For example, whatever I might believe about the assertion “I care about you”, it is fact that those words were written on this platform by some entity that purports to be ‘[the commenter]’.

(Note also that, in that sense above, feelings are facts, whereas beliefs or assertions about those feelings are not facts: see post ‘RBPEA: Feelings are facts’.)

– “What is belief?” – an assertion about the truth of something; likewise, a choice to hold that assertion as true. For example, I choose to believe that the assertion “I care about you” is actually true, and not intended as sarcasm or as a passive-aggressive putdown.

– “What is religion?” – literally, ‘that which binds’. In practice, a structure of belief that guides actions. Such a structure is often referred to as a ‘creed’, from the Latin ‘credo’, ‘I believe’.

– “Who determines what is fact?” – ultimately, ourselves, by testing belief against fact (see below). In practice, to save us some effort, we often tend to take on advice from others as to what is fact or not, using that advice as belief – but the responsibility to test that belief always remains. (This latter point particularly applies to anything that is inherent-difference, such as allergies and the like: what is safe for one person may not be safe for another.)

– “Can you arrive at facts without belief?” – short-answer: no. Longer-answer: we arrive at fact by testing belief – as per that previous definition of ‘fact’, we test to see if the respective ‘it’ stays the same regardless of belief.

– “What is a private matter?” – anything that is inherently personal, and usually beyond our direct control or choice (such as feelings, for example, and also faith as distinct from religion (see e.g. ‘Belief and faith at the point of action’ and ‘Rules, principles, belief and faith’).

– “Who determines what should be a private manner?” – there’s a distinction here between what determines ‘private matter’, versus who might attempt to determine such. The what is that it’s a matter associated with the individual but beyond collective or even individual control (e.g. compare eye-blink reflex, which we can learn to control, versus knee-reflex, which we generally can’t – no matter how much others might demand that we ‘should’). The ‘who’-question is entirely dependent on those distinctions, and largely moot.

– “What does it mean to impose?” – literally, ‘to place upon’. In this context, a demand (maybe backed up by threats of some kind), that others should hold the same beliefs, whether or not those beliefs make sense in practice (i.e. fact-as-experienced) to the individual(s) being imposed-upon. For example, note the crucial distinction between ‘training’ (literally, to force onto a predefined track) versus education (literally, ‘outleading’, assist the individual to find their own meaning and practice).

– “What does it mean to punish others?” – short-answer: to apply sanctions to the Other, because of ‘failure’ by the Other to comply to demands imposed upon the Other.

– “What is social unrest and social damage?” – unrest: literally, ‘the absence of rest’; colloquially, ‘social unrest’ is a shared (i.e. social) lack of peace and tranquillity. Social damage: the means to achieve and maintain social ‘peace and tranquillity’ have become impaired – for example, social division and interpersonal anger have arisen. (The respective means are both individual and collective: e.g. see my work on responsibility as ‘response-ability’.)

– “Who determines what is social unrest and social damage?” – again, note that key distinction between what and who. What determines the existence of social unrest etc is identifiable factors such as degree of social cohesiveness, availability of and access to shared-resources etc (see e.g. my work on enterprise-effectiveness). The ‘who’ comes into the picture in terms of what individuals choose to believe and perceive about those facts (see e.g. ‘Beware of ‘Policy-based evidence’’.)

– “Why should we minimize social unrest and social damage?” – short-answer: because the alternative is usually unpleasant for everyone involved – maybe not to all in the short-term, but almost invariably so in the longer-term. (As with many of your questions, there are longer and more detailed answers, but those may be very long indeed, and this is not a suitable forum for such answers.)

– “Who determines what we should and shouldn’t do?” – ultimately, always each individual. As per ‘private matter’ above, this is ultimately not a choice, even for the individual – no matter how much others might demand that it be so.

– “To what end and why?” – as determined by personal and shared purpose, though arguably POSIWID applies (see Wikipedia on ‘POSIWID’). There’s another whole discussion needed here around spirituality – ’ a sense of meaning and purpose, a sense of self and relationship with that which is greater than self’ – but I’ll address that in a later video.

– “Is this your belief?” – regarding everything above, yes.

– “How do you know?” – in terms of ‘How do I know what I believe’, I practice careful self-observation, not least because there are (or I perceive there to be) many layers of belief, (self)-delusion and so on, within me, and likewise within others. It’s complicated… :wry-grin: I observe how that beliefs that I hold affect and/or influence my interactions with the world and with/for/about others. I do what I can to amend ‘my’ beliefs that do not align well with Reality Department, although, again, it is not always something that I can ‘control’.

For me, the crucial part of ‘How do [I] know’ is that I test each belief. For example, up until now, I have responded to your questions on the belief that they were asked ‘in good faith’ – that you really did mean “I care about you”, as your reason for asking those questions. However, I must now test that belief. The test will be to ask you to give your replies to your own questions. To me, your response – or lack of it – will determine whether I can continue to believe that I can trust you to ask questions ‘in good faith’.

By that point, I’d answered all of his questions, and, as per just above, asked him to show good-faith by providing his answers to the same questions. He didn’t. Instead, he came back with three more questions:

- What do you use to test beliefs and practice self-observation?

- And on what basis, are the things that you use to test beliefs and self-observation reliable such that you can know anything to be fact, objectively true, & reality?

- Are these things your authority for knowledge?

Hmm…

Yeah, at this point, the sealioning-alarm went off full-blast. But okay, again, worth writing some responses to post here. Before that, though, it’s worth throwing in a reply to a seeming throw-away line that came after the questions in that comment:

— “I’d like to explore how consistent or inconsistent your belief model is.”

There’s a huge trap right there. Yes, we need consistency, wherever we can get it. Yet by definition, we’re dealing with a context that is ‘the everything’, yet about which we cannot have other than incomplete knowledge. Hence, by definition, we cannot have absolute consistency across the whole – and any demand for such is, by definition, not only a fool’s errand, but often a dangerous one at that.

Instead, we must identify any inconsistencies that we find, and identify ways to work with those inconsistencies. For example, in my post ‘Declaring the assumptions’, I highlight the limitations of those assumptions, and inconsistencies that can arise if others try to use different assumptions in the same mix.

Perhaps the best summary would be ‘It’s complicated…’ – lots and lots of complications and nuances that I don’t want to dive into here because I simply don’t have the time or energy to do so. The key point is that there’s a balance that needs to be found – a classic ‘It depends‘ and ‘Just enough detail‘ – and getting that balance right is crucial here.

Anyway, back to those follow-on questions that he asked for:

— “What do you use to test beliefs and practice self-observation?”

Self-observation: various forms of meditation, ‘watching the thoughts’ etc; watching for (own) emotions misused as a substitute for or shield against proper observation and reasoning; deep awareness of and action on Gooch’s Paradox (“things not only have to be seen to be believed, but also have to be believed to be seen”); and relentless self-doubt.

(See also the post-series on ‘Seven Sins of Dubious Discipline’, starting at ‘Seven Sins of Dubious Discipline’.)

Testing of beliefs: standard scientific-method (see WIB Beveridge, ‘The Art Of Scientific Investigation’); test for alternatives via engineering-type methods such as TRIZ (e.g. inversion, scale up or down, test at extremes, and other forms of ‘lenscraft’); also methods to use in mass-uniqueness and inherent-uncertainty (see e.g. ‘On mass uniqueness’ and ‘Insights on SCAN – The dangers of belief’.)

— “on what basis, are the things that you use to test beliefs and self-observation reliable such that you can know anything to be fact, objectively true, & reality?”

Short-answer (and probably the only ‘correct’ answer) on ‘objectively true reality’: none. In a strict technical sense, there is no possible way to do so. (See e.g. Paul Feyerabend, ‘Against Method’.)

Instead, as in any technology, my guiding concern is usually less about ‘Is it true?’ in the classic scientism sense, and more on ‘Is it useful?’ – value-focus, not ‘truth’-focus. Again, as in my reply for Q&A #1, Gooch’s Paradox applies: seeing is believing, perhaps, but we first have to sort-of believe it in order to be able to see it. Hence the crucial distinction between asserting that something ‘is true’, versus proceeding ‘as if true’., and then test, test, test, relentlessly, guiding by doubt (science’s ‘falsification-principle’) and self-doubt, every step of the way.

(See also, again, ‘Insights on SCAN – The dangers of belief’, and the chapters in ‘Art of Scientific Investigation’ on the use of chance and intuition, and the hazards and limitations of reason.)

— “Are these things your authority for knowledge?”

Short-answer: my authority for action, yes. As my authority for ‘truth’, probably not – but then I don’t acknowledge any other ‘absolute-authority’ for that, either.

(People whom I would acknowledge as guides who can point me towards something resembling ‘useful-truth’, yes. A strong liking for the advice of Lao Tse, for example, and likewise the classic ‘Advices and Queries’ document of the Quakers, though many, many others too. In each case, though, the classic warning applies: it is unwise to mistake the finger pointing at the moon for the moon itself…)

I acknowledge my responsibility to be ‘self-authoring’ (i.e. the human form of, literally, autopoiesis). I also acknowledge that I’m not especially good at it, and probably never will be – though I challenge myself always to get better at it, even when others don’t or won’t… (e.g. see ‘How do you think?’ and ‘Intimations of arrogance? – an addendum’).

After all of this, the commenter came back again with yet more questions, overall in a form suspiciously close to ‘I demand that you do my thinking for me, and it’s all your fault if I don’t understand it even if I can’t be bothered to read anything or do any of the required work at all’. Yeah, right…

And then he ended with the remark “I don’t understand why you’re running out of patience”.

At which point, yeah, I admit that I really lost my patience… I pointed him to those two posts mentioned earlier above:

Followed by this somewhat short-tempered response from me, echoing what I’d said in those two posts:

Come back to me only when you’ve actually done the work to answer the questions in those posts, and in your comments above. Do not ask me any other questions until you’ve done so.

My guess is that it will take you perhaps 10–20 years to be able to do so in anything resembling an intellectually/spiritually-honest form. I am unlikely to still be alive by that time.

That, bluntly, is why I’m running out of patience: it’s because I’m literally running out of time.

Next?

Oh yes, one other thing that seems relevant here.

Whilst working on this, I was reminded of one of the great Christian apologias: ‘credo quia absurdum est‘, ‘I believe because it is absurd’. To me at least, there’s a lot of sense in that: a key source of deep-anchoring and deep-exploration.

And yet there’s also that counterpoint from Voltaire: ‘Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities’. Ouch…

Leave it at that for now, I guess. But hope it’s useful to someone, anyway.

Without scientific or rational thinking process, can anyone define facts, reason etc?

Facts and reasons can be considered as references from scientific and rational communities or from people who endorse it.

When a person has a no backing on facts, then he simply believe it depending on his urgency and priorities. In other way, beliefs can be a prior-knowledge. For example, we don’t wait for bus or train in a paddy field, instead we wait in a train station as we have prior knowledge that the train comes in a train station. If the train does not come, our brain would search for another prior knowledge for the reasons.

In a scientific context, the phenomenon leads to principles, but religions do it in the reverse order. So, the religious beliefs are more of a sum of tribal thinking.

Largely agreed, LG, though we could perhaps note that what’s generally considered to be ‘scientific thinking’ is not the only rational thinking-process. ‘Scientific’ thinking is a relatively recent development – perhaps only four or five hundred years, in the West at least, though arguably much longer in some cultures, such as the astronomy of classical India. And yet clearly some form of continual-review and assessment has been going on since the dawn of (human) time: consider the craftsmanship of swordsmiths in Japan a thousand years ago, the wayfinders of the Pacific islands, the engineers of the Inca and Toltec pyramids. For record-keeping and retrieval, consider the teller-sticks of Medieval Europe, the quipu of the Incas, or the way in which illiterate women at the time of the French revolution created their own records of executions through patterns in the knitting. You’re right in that this is very different from the ‘I believe because it is absurd’ attitude of (some) religions, but it’s also very different from ‘scientific rationality’ in how it guides assessment and and improvement, and how those improvements are conveyed to the next generation. It’s neither side of C.P. Snow’s classic ‘Two Cultures’ of science or religion, but kind of sideways-on to both, as craft (see e.g. ‘The craft of knowledge-work, the role of theory and the challenge of scale‘). And, for that matter, also sideways-on to art (see e.g. ‘Sensemaking and the swamp-metaphor‘ and ‘Sensemaking – modes and disciplines‘.)