Insights on SCAN: The dangers of belief

And now, the last part in this brief series on insights about the SCAN sensemaking / decision-making framework that arose whilst working on our clean-up, for more general use, of the tools in the inventory. This time it’s about how existing beliefs seduce us into preventing ourselves from doing the sensemaking we need to do during real-time action.

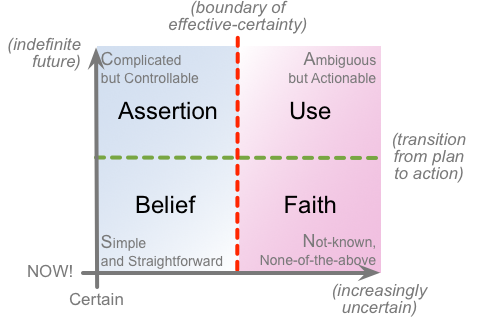

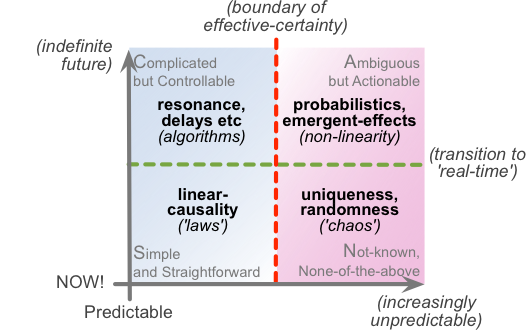

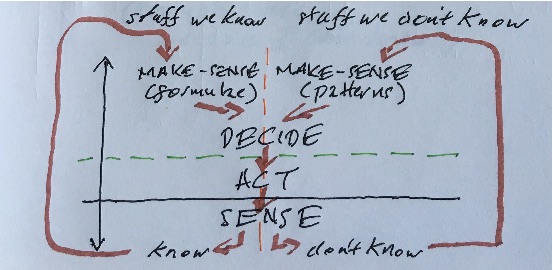

In part this links back to the previous post about SCAN and the Sense / Make-sense / Decide / Act (SMDA) loop – in particular, the distinction between ‘stuff we know’ and ‘stuff we don’t know’ links into separate paths for sensemaking, respectively with predetermined formulae versus inherently-uncertain patterns and guidelines, and how those then connect with the respective modes for sensing within and just after the action. Yet it also connects, perhaps even more, to the decision-making crossmaps for SCAN – about Assertion versus Use, and Belief versus Faith:

I’ll admit that I’ve left these somewhat out of the picture for the past few years, to focus much more on the sensemaking side of SCAN instead. But the decision-making side is also important, as described in posts such as these:

- Belief and faith at the point of action

- Decision-making – belief, fact, theory and practice

- Decision-making – linking intent and action [1]

- Decision-making – linking intent and action [2]

- Decision-making – linking intent and action [3]

- Decision-making – linking intent and action [4]

- Rules, principles, belief and faith

- SCAN as ‘decision-dartboard’

In all cases, all actions, the relationships between sensemaking, decision-making and action still remain much the same, though very much in a fractal or recursive sense, the same pattern repeating at every scope and scale:

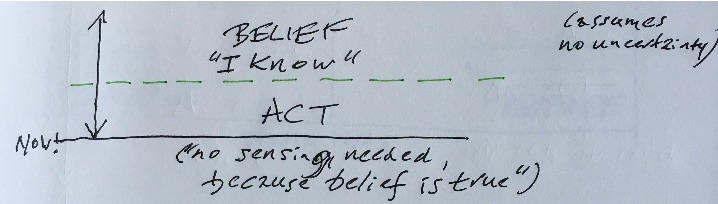

As summarised in the SMDA crossmap for SCAN, sensemaking takes place somewhat away from the action, ‘above the line’ – the horizontal green dashed-line on the frame. Decision-making takes place just before the action – in effect ‘on the line’. And then the action itself, at the moment of the ‘NOW!’ – though shown on the frame as a distinct space, a distinct block of time, in part to allow for that recursion of the pattern:

But because of the recursion, there’s still sensemaking and decision-making that will need to occur ‘below the line’, at or within the real-time action. One reason why it’s useful to separate these out is that when we get close to the action, the mechanisms we use for sensemaking and decision-making will necessarily change, not least because there’s less time available in which to do it. And in humans at least, the mechanisms we use themselves will change, actually using different parts of the brain: the cortex for ‘considered’ assessment ‘above the line’, versus a switch to much more reliance on the limbic-system for decisions within real-time action, ‘below the line’.

For here, the key distinction is about modes of decision-making within real-time action – a distinction that we could describe as the difference between belief versus faith. I’ll likewise admit that ‘belief’ and ‘faith’ aren’t great as terms, but they’re the closest I could find in English that match up to the concepts we need, about real-time decision-making for the supposedly-known, and the accepted-unknown:

What I’ve termed belief is the type of decision-making we can use close to the action, when things are supposedly certain-enough to enable us to rely on predefined work-instructions and the like. All of the thinking should have been done beforehand, to develop those work-instructions, so we can proceed in the belief that those work-instructions are correct and complete. There’s also often a fair amount of ‘I’ there – “I believe” – which, as we’ll see, gets to be important when we come across anything that doesn’t fit the belief.

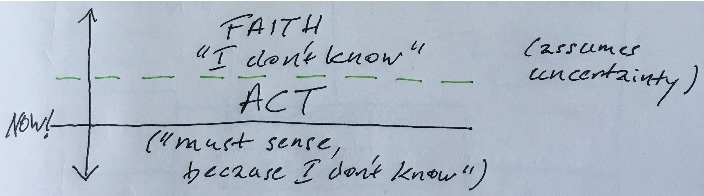

What I’ve termed faith is the type of decision-making we can use – or must use – when we’re close to the action, but in which we either know beforehand, or discover within real-time action, that things are not certain-enough to safely rely on predefined work-instructions and the like. We cannot do all of the thinking and sensemaking beforehand, ‘above the line’, to deliver predefined ‘answers’; instead, the best we could have done is to provide patterns, guidelines, principles and other suchlike ‘seeds’, as anchors around which some kind of usable and useful sense might coalesce. In contrast to the self-centric ‘I’ of “I believe”, here we’re all but forced to look beyond ourselves, to something greater than ourselves, and take it on faith that somehow, within this unknown space, we will have the guidance that we need.

In a sense, what’s going on here with faith-decision is sort-of the same as with belief-decision – which is perhaps why the two terms ‘faith’ and ‘belief’ are so often seen as interchangeable. Yet the feel of each is very different: belief here is very much about ‘I’, the pseudo-certainty of the self and self-centrism, self looking outward at the world; whereas faith here incorporates a deep-acceptance of inherent-uncertainty, unknowability, ineffability, of that which is greater than a mere self-centric ‘I’, and instead accepts the world beyond coming inward to the self. Difficult to describe in words – yet a different feel that is quite distinct within experience.

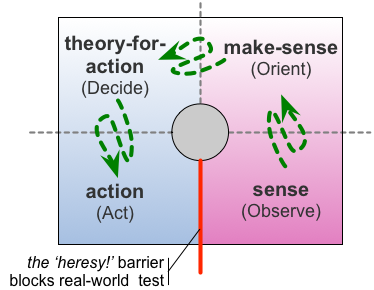

When we allow this ‘outward-in’ mode that I’ve labelled faith, the pattern of sensemaking, decision-making and action follows much the same pattern as in the larger-scope SMDA loop, with faith-type mechanisms providing the core for sensemaking and decision-making, then the action, and sensing that takes place after the action:

The diagram above shows this as the full content for a a single iteration. In engineering terms, though, this can be understood as still a closed-loop, as the sensing from one action feeds into and informs the next.

When the belief-based decision-making is done properly, it works in much the same way, using a brief sensing of the real-world to check that the belief was valid for the current loop, and, if not, to swing over to the faith-based side to decide on action for the next.

But there’s a hidden trap here: there’s a tendency or risk to use the belief itself as a substitute for sensing. After all, by definition the belief must be true, yes? – otherwise we wouldn’t have been told to use it to guide our action. In which case, why bother with the extra effort and time-cost of sensing? – it’ll only slow us down…

And we see people fall for this trap time and time again, in business as much as elsewhere – especially if they’re under pressure to ‘produce, produce, produce!’.

Without sensing, the action can run only open-loop – endlessly repeating the same action, whether or not it matches appropriately with its real-world context. In any machine environment, there must be some part of the overall system that does the sensing, and can steer the ship against the changing tides – otherwise the system will fail, and often apparently ‘without warning’.

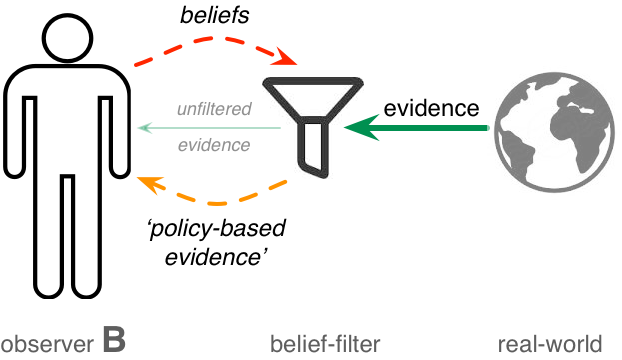

In a human context, it can often be even worse, because belief is often embedded via emotion – in effect, the circular-reasoning that a given belief is ‘The Truth’ because it is believed to be true. If that happens, risk falling into a self-reinforcing, self-circular echo-chamber loop of ‘policy-based evidence‘ and the like, where any real-world evidence that might arise is first screened through a filter of existing beliefs, and almost all contrary evidence is blocked from view:

And since the belief is ‘The Truth’, if there is any contradiction between the real-world and the expectations of the belief, it is therefore the real-world – not the belief – that is deemed to be ‘wrong’. The further the real-world diverges from the expectations of the belief, the greater the emotional intensity – in effect, an increasingly-amplified fear of uncertainty. This emotion can easily spiral into yet another self-reinforcing feedback-loop, as evidenced in the outright hatred thrown at any purported form of apostasy or heresy – the latter being a term which merely means ‘to think differently’. We see this even in the classic science-development sequence of ‘idea / hypothesis / theory / law’, where the over-certainty of ‘law’ provides an active ‘heresy-barrier’ against any new ideas:

No doubt it seems much easier and more comfortable to avoid all of that emotion by hiding away in that self-centred, self-righteous, self-confirming echo-chamber. Not so wise, though, if doing so drives self-reinforcing delusions about the real-world – because such delusions can indeed become deadly in an all too literal sense. The fate of 17th-century admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell provides a useful cautionary tale in this regard…

The advantage of open-loop Belief-centric decision-making is that it runs faster – sometimes much faster – than a proper sensing-checked SMDA closed-loop.

The disadvantage is that it is, at best, very brittle, and can often be just plain wrong – with no means to test why, how, or even whether, it is wrong.

Overall, Belief-based decision-making, without crosschecks, is comforting, fast, and very dangerous, especially in conditions of rapid and/or large-scale change. It also has a huge risk of dependence on Other-blame or Other-abuse as a means to maintain any literally-unrealistic beliefs. In politics and religion in particular, there is often an almost total reliance not only on unexamined Belief, but on intense Other-abuse in order to prevent examination of those beliefs. Not A Good Idea…

SCAN-mapping is helpful here because it provides a checklist to help highlight known warning-signs:

- pressure to run the SMDA loop so fast that it can only be run open-loop, with little to no time available for sensing and/or review

- any tendency towards self-confirming Belief, with explicit exclusion of conflicting evidence

- absence or exclusion of any means to collect any evidence that contradicts the Belief

- inadequate or non-existent support for the Faith uncertainty-oriented side of the full SMDA loop

- inadequate or non-existent means to switch from Belief to Faith, and back again, within the design or structure of the overall system

You Have Been Warned, and all that…?

Hope this has been useful, anyway – and over to you for comments and suchlike, should you wish.

Leave a Reply