Business-models between for-profit and not-for-profit

Is money the only possible form of profit? And if not, what does that imply for design of business-models? – and, beyond that, to economics itself?

This is one that I’ve been struggling with, both personally and professionally, for a very long time now. To be honest, I don’t think I’m all that much closer to a viable answer at present: but the struggle and the challenges do seem worth sharing with others, to see if there’s some possibility that between us that we can crowdsource something that might actually work.

What brought this to a head for me right now was a conversation with an Australian colleague, Helena Read, about the work of Muhammad Yunus, founder of Grameen Bank, and author of ‘Building Social Business‘. Note, though, that it’s a rather specific meaning of ‘social business’:

Social business is a cause-driven business. In a social business, the investors/owners can gradually recoup the money invested, but cannot take any dividend beyond that point. Purpose of the investment is purely to achieve one or more social objectives through the operation of the company, no personal gain is desired by the investors. … The impact of the business on people or environment, rather the amount of profit made in a given period measures the success of social business. Sustainability of the company indicates that it is running as a business. The objective of the company is to achieve social goal/s.

This is significantly different to the kind of definition of ‘social business’ that many of my ‘#socbiz‘ colleagues here would use, or the drivers that they would describe within and beyond the organisation. Yet is there some way to bring those definitions closer together? I think there is – though to do so requires us to rethink somewhat our understanding of ‘profit’.

Mainstream economics describes profit – in fact just about every aspect of the economy – almost exclusively in monetary terms. Hence, in turn, we get the strict split into two forms of economic activity:

- for-profit: the sole purpose of the organisation is monetary return to investors

- not-for-profit: the sole purpose of the organisation is ‘something else’, and must not provide monetary return to the investors

Financial-return is often deemed to be the determining-factor as to what type of business an organisation does, and what type of law should apply to govern it. Cooperative businesses may have different business-drivers, but their supposed nominal aim is to ‘make money’ for their members, so they’re classed as a special case of for-profit. Government takes money from others, but isn’t supposed to ‘make money’, so it’s a special-case of not-for-profit. If it’s a for-profit organisation, people should be paid; if it’s a not-for-profit, the apparent ideal is that no-one should be paid. That’s it: the only choices.

(Social-conservatives sometimes take the latter case to extremes, and say that there should be no government at all: every social service and every function of government should be delivered by unpaid volunteers, who will come from, uh, somewhere – though any question as to exactly where that ‘somewhere’ might be, or how it might actually be organised, is swiftly sidestepped as Somebody Else’s Problem…)

All nicely simple, easy to understand, easy to enforce – and ludicrously incomplete. Oops…

In short, it doesn’t work. Or, to be pedantic, it does sort-of work for an increasingly narrow subset of organisations – leaving the rest with business-models that really do not and cannot work well, if at all.

In reality, there’s a whole spectrum of business-models that exist between those two extremes, and financial-return is merely one factor amongst many that we should consider. To me it seems likely that key drivers for this paucity of thought on business-model drivers would include:

- an historical focus on money as a trading-medium in a possession-based culture has led to the monetarist-economics delusion that money is the only relevant factor in economics – a term-hijack that has created perhaps the worst possible system for resource-allocation that anyone could devise

- a steady whittling-away of investor-responsibilities has led to an ‘investor-as-owner’ model (stock-exchanges etc) worldwide that frequently assigns highest ‘ownership-rights’ to investors with most destructive relationships and least responsibilities – scavenger first, symbiote last

But whatever the reason, the fact is that the usual finance-only description doesn’t work well enough to make usable sense at any scale. To make it work, we need to restart almost from scratch, with a rethink of what we actually mean by ‘business’, and a much better understanding of its real drivers.

I’ll use my own case to illustrate this. Start with Business Model Canvas [BMC]:

As is usual with BMC, I’d start with a list of the core ‘things that I sell’ (Value Propositions, shown as yellow ‘sticky-notes’), and build outward from there – Partners, Customers, Channels, Activities, Resources and so on:

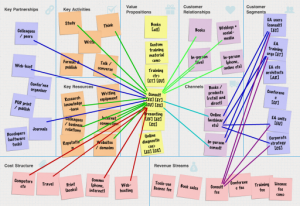

I’d then typically show some of the flows and inter-relationships between all of these various items, to build up a sense of how the business-model actually works – such as in this summary for my ‘Consulting’ value-proposition:

The links to the pink-coloured ‘sticky-notes’ in the bottom-row summarise my financial-costs (Cost Structure, on the left) and financial-returns (Revenue Streams, on the right) – with the difference between them being my profit or loss.

It does all sort-of make sense, for those costs and returns that can be described in financial terms. The catch is that there’s no means here to describe costs and returns that are not financial – yet for many business-models, those are the costs and returns that matter the most.

From the point of view of the business itself, in most cases money is just a side-issue, a necessary requirement in order to do the real business of the business within a money-based possession-economy. Charles Handy summarised this point well with a sporting metaphor: “we don’t play cricket in order to get a good batting-average”, he said; “it’s just that we need a good batting-average to continue playing in first-class cricket”.

We won’t be able to keep going in business without ‘making money’, but as Daniel Pink and others have shown, ‘making money’ is not a good driver for business itself. We need to keep track of money-flow in a business-model and business-operations, but it’s very definitely not the only thing that we should track.

(In reality, the only people who are only interested in what money the business makes are parasite-investors – perhaps not the best people to be defining our organisation’s business-model?)

Worse, for me and, I know, for many others, ‘making money’ is an anti-driver for business – it’s exactly what our business is not about. A personal example: the other day I was in one of the local cafes, working on the structure and story for my current EA book. I finished what I was doing, got up to go, and noticed that the guy at the next table was reading a book called The $100 Startup. Being my usual happily-intrusive self, I struck up a conversation. He’s in his late 40s, having worked in government all his working-life, knows it’s time for a change, wants to start up something on his own, “maybe trucking, maybe a restaurant, I don’t know”. A long way to go to a solid business-model, then. But we talk for a while – some half an hour, perhaps – and I point him to various sources such as Business Model You and What Color Is Your Parachute?, all of which he notes with real interest on his smartphone. He got real value out of the conversation, and so did I – it felt like what I’m in business for, to help people find value in their own work.

The conversation was commercially valuable for him – particularly over the longer-term – and the service was delivered at a real time-cost to me. In the kind of business-contexts where I usually work, I ‘should’ have charged upwards of a hundred pounds or so for that piece of admittedly-unsolicited consulting. Yet it felt important that no money changed hands there: to put it at its simplest, it wasn’t that kind of business. The catch, for me, is that rather too much of my business is this kind of ‘it’s not about money’ business: as I say sometimes, somewhat ruefully, “I’m always working, and occasionally someone pays me”. In this insane economics that we live in, I do need find a way to pay my way somehow: yet most of what I do, and most of what drives me in my work, is such a long long way away from the kind of simple ‘quid pro quo’ that conventional money-based business-models expect, that talking in monetary terms simply doesn’t make sense. It’s not a not-for-profit charity, but it’s also not solely a money-centred for-profit business either: it’s somewhere blurrily in the middle that our current economics-models don’t acknowledge at all. Tricky…

Yet it’s not just that the money side of business gets in the way here: more, it often feels like an outright insult to even bring money into the picture. Imagine that you’re at your mother’s house, she’s cooked a special family meal: would you whip out your credit-card and ask her for the bill, the check? Not a good idea… reducing the relationship there to monetary terms really doesn’t work, in fact is an almost-guaranteed way to damage or destroy the relationship. There are very different values and forms of value at play in that interaction.

And that frequently extends to business too: the whole money-mess often feels personally obscene. As one colleague wryly put it some years ago, about the consultant’s life, “are you a prostitute, or a pimp?” – as a consultant, do you sell your own ‘personal services’, or do you procure and sell the ‘personal services’ of others? When I do consultancy-work, I’m not selling some abstract impersonal ‘thing’, what I’m selling is me – and converting that relationship solely to money really does have that obscene feel of prostituting myself, in the worst possible sense. Yuck…

In fact that almost perfectly summarises that rigid split between ‘for-profit’ versus ‘not-for-profit’:

- for-profit: body, mind and soul are sold to ‘make money’ = prostitution

- not-for-profit: everything of life must be given away ‘for free’ = destitution

Prostitution or destitution: often seems like those are the only two options that a money-based economics can offer us. Not a good choice to face: no wonder our economics is in such a mess… In short, we really need a better range of choice than that!

Which, in turn, means we really need to rethink and reframe what we mean by ‘business-model’ – restarting right from scratch.

I described the core principles for this some while back in my post ‘Modelling mixed-value in Enterprise Canvas‘, and it’s worth revisiting those principles here.

Start from the core idea that everything is or represents a service – an entity that delivers services of some kind, and also (usually) consumes services of some kind. An ecosystem of any form – business or otherwise is a web of interacting, interdependent services. This applies at every possible scale, from the smallest mote to an entire ecosystem as a whole.

A service serves. The underlying ‘why‘ or purpose for the service may be purely mechanical (as in non-living systems, following ‘laws’ such as those that underpin entropy), or partially or explicitly intentional (as in living-systems, which almost by definition are capable of creating some form of local reverse-entropy, if only at the species-level). In a business context, the ‘why’ may only be implicit (as in POSIWID), but preferably has some explicit intentionality to it (such as vision and strategy).

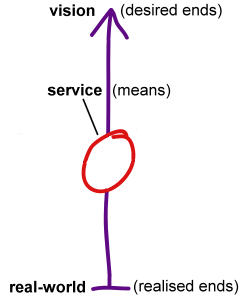

The ‘why’ for a service creates a tension between the desired-ends (definite and/or indefinite future) versus the realised-ends (what has been or is at present being achieved). This tension can be described in terms of values, as both drivers for action and criteria for success-in-action. The service represents a means via which a striving towards the desired-ends is made possible – and also a means via which the values can be expressed in real-world practice:

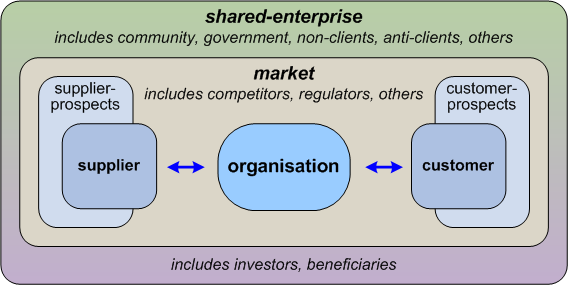

In a shared ecosystem, shared, interdependent and/or mutually-supportive values link the various players in the ecosystem together. Or, to put it the other round, the values of each player in the ecosystem must in some way support the shared-values of the ecosystem as a whole. (Note that this includes relationships such as predator/prey, or scavenger-as-recycler.)

Each player – each service-entity – engages in exchanges of value with other players: it is a provider of services (to ‘customers’) and a consumer of other services (from ‘suppliers’). (The player may also have partners with whom it has relationships as both ‘provider’ and ‘consumer’.)

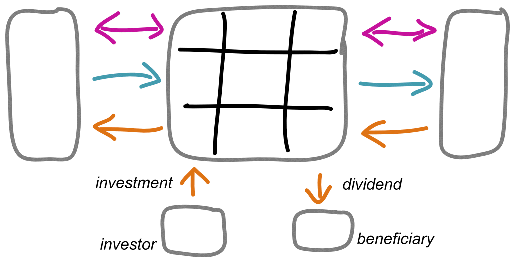

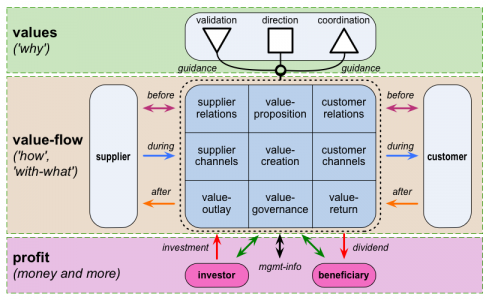

To make better sense of that flow of value between players, it can be useful to partition the service into a three-by-three matrix of ‘child-services’ – the matrix being formed from a time-dimension (before, during and after the main service-transactions) and an orientation-dimension (inbound [service-consumption], self [value-creation] and outbound [service-provision]):

The arrows in the diagram indicate the emphasis of value-flow at each stage, which also often carry different types of assets and value. In a business-context, the stages would typically emphasise:

- ‘before’: relational/aspirational-assets – establish shared-connection and shared-purpose for value-transaction, based on this service’s ‘value-proposition’ [BMC: Customer Relations, implied Partner relations]

- ‘during’: usually exchangeable assets (physical/virtual), in terms of this service’s value-proposition [BMC: Channels, implied Partner channels]

- ‘after’: usually exchangeable assets (physical/virtual), for completions in relation to the value-proposition [BMC: Revenue Streams, Cost Structure]

If we translate this into a conventional business-model, we provide a product or service to a customer (‘during’), who then pays for it (‘after’ – ‘revenue stream’); and we obtain a product or service from a supplier (‘during’), and then pay them for it (‘after’ – ‘cost structure’). Note that the forms of value are usually different in the respective stages and value-flows: goods or services in the ‘during’ stage, versus payment or some other form of ‘compensation’ in the ‘after’ stage.

An essential point here, though, is that the forms of value are always in the context of the values or overall drivers for the service: the distinction between ‘value’ (‘horizontal’) versus ‘values’ (‘vertical’) is perhaps somewhat subtle, but is crucial here:

— The service’s vision and its concomitant values provide the the ‘why’ or reason that customers and suppliers choose to ‘do business’ with the service.

— Declaring that the service’s only vision is “to maximise financial returns to stockholders” tends to be a fairly serious disincentive to those who would be the source for those ‘financial returns’… it kinda devalues the service’s ‘value-proposition’ for others.

To validate the value-proposition, we need a vision that includes our business-partners and their aims – not one that treats them solely as objects to be milked into oblivion – and that links the various value-exchanges into a ‘story’ that has meaning for everyone involved.

In practice, the service often needs the assistance of other services – ‘guidance-services‘ for validation, direction and coordination – to help it on track to its vision. In Enterprise Canvas sketch-notation we’d typically show the guidance-services like this, as another set of related services ‘above’ the service that we’re interested in, and each tagged with the respective symbol:

The guidance-services intersect with the business-model, but are usually not regarded as central to the business-model itself. It’s very different, though, when we look at the other ‘external’ relationships in Enterprise Canvas, the links with the service’s investors and beneficiaries: a business-model is not complete unless it also describes its relationships and interactions with investors and beneficiaries. We typically show these ‘below’ the respective service-in-focus:

For example, these investor/beneficiary relationships are central to the split between for-profit and not-for-profit. That split assumes that the only relevant form of value is money, and that ‘profit’ is therefore defined as the monetary-value extracted by or for the beneficiaries from the operation of the business-model. Hence:

- for-profit: investor invests money (BMC: input to Cost-Structure), receives monetary-return as beneficiary (BMC: output from Revenue-Streams); primary external focus is on balance between investment and return (‘the [stock]market’)

- not-for-profit: investor invests money (input to Cost-Structure); no return in monetary form, therefore beneficiaries deemed not to exist (or are viewed as the ‘consumers’ of provided services – the transaction/’during’ interactions, not the backchannel/’past’ interactions); primary external focus is on investment (‘fundraising’)

In both for-profit and not-for-profit, staff are usually viewed solely in terms of Cost-Structure: employees are classed as monetary ‘costs’, whilst volunteers are categorised as ‘zero-cost employees’.

All of which should tell us that a monetary-only business-model is woefully incomplete…

To understand the business-model properly, we need to describe:

- all forms of value and value-interactions that apply in that business-context

- the interchanges (transforms) between forms of value

- the relationship of each form of value and value-transform to the vision and values for the service (‘the business’ or ‘the enterprise‘)

- the stakeholders from whom and/or to whom each form of value is provided

- the effective value-relationships between each of the stakeholder-groups

- the effective overall value/values balance for each stakeholder-group, to underpin a concept of ‘fair exchange’ in relation to the enterprise vision and values

The last point is extremely important: in the longer-term, a business-model is viable only if it provides ‘fair exchange’ for all of its stakeholders.

The service ‘creates value’ by the way in which it does value-transforms, in line with the values of the service and in relation to the values of the overall shared-enterprise or ecosystem. The service’s Value-Proposition is therefore much more than just a description of product-attributes or the like: it has to demonstrate how its various value-transforms provide ‘meaningful value’ and ‘fair exchange’ for all of the service’s stakeholders.

Again, the simplistic monetary-only ‘profit = price minus cost-of-production’ is woefully-inadequate for this. I won’t go into the detailed reasons here (because this article is too long already…), but in essence we need to summarise the exchanges and transforms in terms of the full set of asset-dimensions:

- physical asset-dimension: physical objects, physical ‘things’ – independent, tangible, exchangeable, alienable

- virtual asset-dimension: data, information – nominally-independent, abstract/non-tangible, non-alienable, ‘exchanged’ via copy

- relational asset-dimension: relations/connections between people – interpersonal/dependent on both parties, both parties are tangible, non-alienable, non-exchangeable but potentially replicable

- aspirational asset-dimension: anchor-point for ‘belonging’, motivation etc (e.g. as represented by brand) – personal / dependent on both parties; one party tangible, the other (e.g. brand) usually not; non-alienable, non-exchangeable but potentially replicable

Most assets and asset-interactions (service-flows) involve multiple asset-dimensions. For example, a printed-book is a composite of physical (the book itself) and virtual (the information contained in the book); money is a composite of virtual (information about quantity and money-type) and aspirational (‘belonging’ to the implied brand of a fiat-currency) and occasionally physical too (as cash – coin or notes). A composite has to be managed in terms of all of its asset-dimensions: hence a printed-book must be managed as both physical (inventory, storage etc) and virtual (copyright, version-control etc).

Assets pass through the horizontal flows between services in Enterprise Canvas:

Importantly, though, the types of assets that typify each of the ‘before’, ‘during’ and ‘after’ flows across and between the services:

- before-flows: primarily relational and/or aspirational assets

- during-flows: primarily exchangeable asset-types – physical and/or virtual

- after-flows: primarily information and/or money (virtual/aspirational composite)

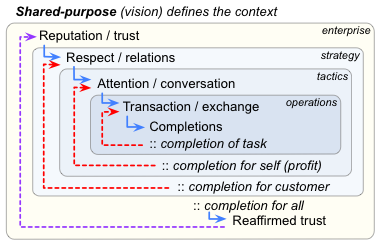

We see much the same happening within the related Service Cycle: aspirational-assets (reputation and trust), then relational-assets (respect and relations), virtual-assets (the information to support attention and conversation), then physical and/or virtual-assets (the transaction, in the ‘during’-flow); and then the reverse order to close the whole cycle.

Other flows in Enterprise Canvas – such as with the guidance-services, and management-information flows between service-‘layers’ – tend primarily to be information (virtual-assets):

The ‘investment’ and ‘dividend’ exchanges with investors and beneficiaries may be any type of asset. In a commercial business, this may often be money, but that is not always so at all – as described in more detail in the post ‘Every organisation is ‘for-profit’‘. We could perhaps summarise this visually as follows:

Which also lines up with a visual summary of the organisation in relation to its market and broader shared-enterprise:

To summarise everything above:

- the usual sharp-edged distinction between ‘for-profit’ and ‘not-for-profit’ is often wildly-misleading – especially for larger-scope concerns such as enterprise-architecture and business-architecture

- almost all real-world business-models lie somewhere on a spectrum between ‘for-monetary-profit’ and ‘not-for-monetary-profit’ – often in a much more blurry form than current assumptions of legislation expect or allow

- in order to make full sense of how a business-model actually works, we need to understand and track all of its asset-types and asset-transforms – not solely the monetary flows

- whole-of-context model-types such as Enterprise Canvas and its Service Cycle can help in this, by providing a frame in which those asset-flows and asset-transforms can make sense

Once again, there’s no particular point I’m making here, other than that I hope this is useful towards building a better understanding of business-models, and the broader business of organisations in general.

Over to you for comment, perhaps?

I find it interesting, maybe troubling, that this, one of your most important observations about enterprise, has provoked no comments. Maybe it’s just the time of year.

You start by saying:

“This is one that I’ve been struggling with, both personally and professionally, for a very long time now.”

I think this may be because, at least in my opinion, you are looking through the wrong end of the telescope.

In your earlier essay, you say “all organizations are ‘for-profit'”. I think this is a needlessly “business-colored” way to frame the issue. It may be a useful way to open the conversation with people whose perspective is dominated by the idea of “business”, but as I have noted elsewhere it’s often the connotations of words rather than their denotations that affect how we think about the details of the concepts we use these words to describe, and “profit” carries considerable connotative baggage.

“Profit” is an instance of the class of things that we variously call “goal”, “purpose”, “intent”, or “desired outcome”. At some point, we, as a community of professional enterprise architects, are going to have to pin down exactly what we use these words to mean, and how they relate to one another, but that’s a substantial exercise, and for the time being what we generally understand these words to be about should be suitable enough for me to make my point.

In a nutshell, I’d argue that “profit” is not the proper class to be considering, nor is it a proper name for the class, given that connotative baggage. “Profit”, for any reasonable definition of the word, is only one of many possible “desired outcomes” for an enterprise, at least for enterprise in the sense of “ambitious undertaking”.

But first, a parenthetic observation. We, as a community of enterprise architects, are almost obsessed with models. I have argued elsewhere that we ought to be at least as obsessed with principles, but that’s a discussion for another place and time. We also have a similar “almost obsession” with universals, especially universally applicable models.

The confluence of these two “almost obsessions” has a downside, and that is an unduly common predisposition to let the models we make assume precedence over the things they are models of, or worse, things they were not meant to be models of. There are many appealing reasons that we do this, all understandable in terms of human nature, but appeal and sensibility are explanations, not justifications. When we divorce models from their raison d’etre as representations of something that we have simplified in ways carefully chosen to make the model tractable as an explanatory or exploratory mechanism, we put their usefulness and value as models at risk. One of the most common ways we do this is to recast the way we think about real world situations so they fit the models we have become enamored of. This is nicely illustrated by one of my favorite folktales, one version of which is called “Zumbach the Tailor”. Just as Zumbach makes the customer accommodate the suit rather than vice versa, we look for ways to make the real world accommodate our model, rather than vice versa.

In this case, the (universal) model is “profit”, and the real world situation is a diversity of desired outcomes. I suggest that not every desired outcome of an enterprise is best thought of as some form of “profit”, and corollary to this, the essence of every enterprise may not be best modeled by an Osterwalder/Pigneur Business Model Canvas, even if it is ideal for modeling the business/commerce aspects of the enterprise. Acknowledging this observation requires that we resist the temptation to make “business” into a “Zumbach suit” by claiming that “business” also means “primary concern” (e.g., “the business of the Army is fighting ground wars”), and that this sense of the word automatically applies to all uses of the word.

Finally, I have to push back a bit on the idea of “sole purpose”. I don’t think any enterprise has a “sole purpose”, at least in the sense of a single, atomic (i.e., unstructured) desired outcome. Enterprises by their nature generally pursue complex outcomes within complex constraints on what constitute acceptable means of achieving these outcomes, and it is the interactions between these that make enterprises nontrivial undertakings, and thus an appropriate subject for the application of architectural thinking.

len.

Many thanks for the reply on this, Len – and especially so as I was likewise a bit disappointed that, yes, as you put it, it was one of my “more important observations” but had previously “provoked no comment”.

A quick explanation about the link between this and the ‘Every organisation is ‘for-profit’‘ post. Reality is that I actually wrote most of this post maybe as much as a year ago: it was sitting in my WordPress ‘Drafts’ folder, and I realised that I needed to finish it and get it out there. The result, though, is that some parts kinda clash with the nominally-‘earlier’ post – exactly as you’ve seen. Sorry…

I still don’t get why you think I’m “looking through the wrong end of the telescope” – but that’s more my fault than yours, I’d guess? 🙁

All I can guess here is that, once again, we have a clash on terminology. At present the only way I can interpret what you’ve said above is that you still seem to prefer much narrower, ‘term-hijacked’ versions of key terms than I would use – in this case, particularly for ‘profit’ and ‘enterprise’ – or, as above, kinda complain that I’m confusing things by not assuming or complying with the respective term-hijacks, by not assuming that ‘profit’ is only about money, or that ‘enterprise’ is a near-synonym for ‘the organisation’. The whole point of my work here is that they’re not the same, and that (mis)using them as if they are the same causes all manner of scope-myopia and conflation-problems that can be very difficult to resolve unless we do drop the term-hijacks. (This is the exact same problem as with IT-centric ‘EA’ pretending to claim the entire scope of EA – but let’s not go round those loops all over again, especially as we largely agree on that anyway! 🙂 )

I take your point about the twin ‘obsessions’ of models and universalities: yeah, real problems there… Yet both obsessions are valid in their own way: the problems arise when people mistake them for ‘truths’ rather than tools. In the case of Business Model Canvas, for example, I personally don’t regard it as ‘the truth’ about business-architecture (though I know that some people do): I used it above because people know it and are familiar with it and would understand the examples in those terms, but yes, I’m well aware of its constraints and limitations – resolving those was a large part of what Enterprise Canvas was about, after all.

@Len: “‘Profit’ is an instance of the class of things that we variously call ‘goal’, ‘purpose’, ‘intent’, or ‘desired outcome’.”

No, it isn’t – and that’s really important here. It’s not a member of that class at all: the return of profit is a desired-outcome, but if we treat profit itself as a desired-outcome, in the same sense as ‘goal’ or ‘intent’, we’d be seriously confusing the issues here. As a comparable example, in most cases people really don’t need ‘money’ as a goal: they need money as a means towards some other goal – not as the goal itself. (And if they do treat money itself as a goal, they tend to get themselves and/or others into all manner of nasty messes – as can be seen all too clearly all around us…)

The other point – as explained in some depth in the ‘Every organisation is for-profit’ post – is that we must break out of the term-hijack of viewing profit solely in monetary terms. (For example, consider ‘profit’ in the Biblical sense, as “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?”) I could be a bit blunt and suggest that the one of us here who’s thinking in “a needlessly ‘business-colored’ way” is not me at all…

@Len: “Finally, I have to push back a bit on the idea of ‘sole purpose’. I don’t think any enterprise has a ‘sole purpose’, at least in the sense of a single, atomic (i.e., unstructured) desired outcome.”

Again, you’ve put up a (presumably-unintentional) straw-man here, interpreting what I’ve said in terms of a common yet fundamentally-inappropriate term-hijack – as illustrated by your next sentence, around “Enterprises by their nature…”. I need to hammer this one really hard: ‘organisation’ and ‘enterprise’ are not the same. In praticular, trying to describe ‘the organisation’ as ‘the enterprise’ – as per ISO42010 and suchlike – will guarantee a descent into an irreconcilable mess of circularities. Keep them separate, keep them separate, keep them separate!

Once again: an enterprise is an emotive construct, a ‘why’ – that which underpins people’s being enterprising. For practical purposes, I define an enterprise as having a singular purpose – that’s its definition, that an enterprise is circumscribed and delimited by a single idea or ‘vision’ or ‘promise’. There is a recursion here, of sorts, in that within a single vision, there are often correspondences to or interdependencies with or on other enterprises – in much the same sense as ‘systems-of-systems’, for example – but an enterprise itself is always singular. That’s core to ISO9000:2000, by the way: the moment we lapse on that assertion of singularity, the whole quality-system is placed at risk of collapse, through loss of clarity on relative priorities for policies and principles.

By contrast, an organisation is a structural and/or legal construct, a ‘how’ and/or ‘with-what’ – that which organises people towards the shared aims of their ‘enterprisingness’. And yes, an organisation may connect itself to many enterprises, in the sense described above (though it risks loss of clarity in doing so). Every person certainly does connect to many enterprises, both personal and collective – that’s part of what makes organisation so darned hard! 🙂

But again, it’s really, really important to get clarity on this one – otherwise the architecture ends up going round in circles on its own circularities, going nowhere.

We’re clearly not communicating. I understand the idea of (and have long and regularly argued against) “term hijacking”, and am simply astonished that you would assert that that’s what I’m doing here.

You must have forgotten the long piece I wrote on how enterprise and organization are different things, and I am at a loss as to why I deserved this lecture on something we have long agreed on.

Really — dismissing my entire argument as term hijacking. I have clearly failed to express myself clearly.

Rather then repeat myself, I’ll just leave it as, you’ve completely missed the points I was making.

len.

Hi Len

“We’re clearly not communicating.” – sadly, I fear that’s true. Other than how I’d interpreted your previous comment, as per above, I have no idea what you’re saying. Which is not good. Oh well.

“I have clearly failed to express myself clearly.” – applies just as much to me, obviously – probably more so than to you, in fact. Again, my apologies.

As you say, best to leave it there for the moment, until we can find a suitable hook or example where we can each understand what the other means.

But at the very least, thanks again for engaging, anyway – much appreciated.

OK, I’ve given this some more thought, and I’ll try to explain my reasoning.

First, it seems to me that you are proposing to redefine “profit” by generalizing its current widely accepted meaning. Look the word up in any dictionary. Its primary definition is almost always about money, specifically about the excess of revenues over costs.

My observation was that the strong connotations associated with the current widely accepted definition of “profit” makes your proposed repurposing of the word a challenging enterprise at best. You are certainly free to try to do so, but one might ask if this is necessary. Are there no other words that are already closer in meaning to your generalized concept, and whose use for that purpose will not require that we find another word to represent the (useful) conventional meaning of the repurposed word?

It is not “term hijacking” to point out that a word already has a widely accepted meaning, that that meaning is useful, and that if the word is repurposed, we must adopt another word to denote the useful concept this word is already widely used to represent.

Nor is the use of the word “profit” to mean “difference between revenues and costs” or something like that a form of “term hijacking”. It is using the word as it is defined, and not some secondary or tertiary definition.

Since you have not actually proposed a specific definition for your generalization of “profit”, I can only try to make an informed guess at what it might be. It seems to have something to do with “benefit”. A benefit is a result or outcome that is perceived to be of value.

The question I am implicitly asking is “must we assume that an intended outcome is always of value?”. Or is it enough to simply focus on the achievement of an intended outcome regardless of its perceived value? What is beneficial to one party may not be perceived as such by another party. It seems to me that “value” is a perspective-dependent property of an outcome.

It is in this sense that I question whether some generalization of the idea of “profit” is the right way to think about why we create organizations to realize enterprises, and that I think that some generalization of the idea of “outcome” is a more encompassing concept.

Did that help?

len.

Hi Len – again, many thanks for the effort you’re putting into this. I know I’m not exactly the easiest of people to work with, and this is a really challenging one – yet it’s also absolutely fundamental if we (not just you and I, but the whole, collectively) are to have any chance of breaking out of some really lethal roadblocks in enterprise-architecture and beyond.

@Len: “First, it seems to me that you are proposing to redefine “profit” by generalizing its current widely accepted meaning.”

This is really important: I’m not the one doing the redefining. All I’m doing is reaffirming an existing more generalised meaning, with a much longer history than the money-only one (as can be seen from that quote earlier from the King James edition of the Bible). The ‘profit=money’ notion is a later term-hijack, arbitrarily constraining the meaning to a very narrow subset – and one that, if we do allow that term-hijack to go unchallenged, makes it all but impossible to describe how anything other than a money-oriented ‘enterprise’ actually works. (Historically, the ‘profit=money’ term-hijack closely parallels the equally-daft term-hijack of ‘economics=money’. The literal meaning of ‘economics’ is ‘the management of the household’, encompassing everything needed in order to manage a household – of which the money is only one minor part, and often the easiest part at that…)

Interestingly, the difference is very clear in two different definitions in Business Model Generation. On p.14, he states that “A business model describes the rationale of how an organisation creates, delivers and captures value.” (That’s pretty close to your ‘informed guess’ about “something to do with ‘benefit’. A benefit is a result or outcome that is perceived to be of value.”) Yet in the last paragraph of p.15, he instead says that “a business model … show[s] the logic of how a company intends to make money.” In other words, and without any preamble or justification, he’s arbitrarily constrained ‘value’ to ‘money’ alone – a classic term-hijack, that in fact makes it impossible to describe how the business-model actually works, in terms of its overall value-flows and the like. (That’s a key reason why Business Model Canvas tends to be problematic in practice, especially at a whole-enterprise-architecture scope.)

@Len: “It seems to me that “value” is a perspective-dependent property of an outcome.”

Yes, it is. And so is ‘profit’ – even in monetary-only form. One of the huge problems of a money-oriented view of profit is that gives a spurious sense of precision, certainty and ‘objectivity’ to something that is none of those things at all. Only by pulling back out, and exposing the term-hijack for what it is, do we start to create options to deal more openly and honestly with the real ‘messiness’ that purported ‘profit’ actually implies.

@Len: “I think that some generalization of the idea of “outcome” is a more encompassing concept.”

This brings us back to a point that you hadn’t responded to as yet, namely that ‘profit’ is not a member of the same set as ‘goal, purpose, intent, outcome’. If you try to treat it as an instance of that same set, then yes, you’re going to fall straight into the kind of circularities I warned about above, because they are fundamentally different. Profit – and especially monetary-profit – is a side-effect of achieving a goal or suchlike. If we treat it as a ‘goal’ in its own right, it will distract from the actual goals etc that must be achieved in order for that profit to arise. Charles Handy put it well in a cricket analogy: “we don’t play cricket in order to get a good batting-average – even we need a good batting-average to be able to play in first-class cricket”. The monetary-profit of a business is like the batting-average – but the batting-average isn’t the reason why people engage in the ‘enterprise’ of cricket.

Does that make anything any clearer? – or have I merely stirred it into impenetrable murk all over again? 😐

One more try, to see if I can describe this visually.

If the term-hijack is not in place, and we have clear distinctions between values (determined by the shared-enterprise), value (determined by the services and and service-flows of the organisation) and profit (value of any appropriate form returned to the many-and-various stakeholder-groups), what we end up with is a description of ‘organisation-as-service’ that looks like this:

But if the ‘profit=money’ / ‘money-is-the-only-value’ term-hijack is in place, we end up with a Taylorist-style notion of ‘the enterprise’ (organisation as ‘machine-for-making-money’ for a single self-selected group of stakeholders who claim to be the exclusive ‘owners’ of the entire shared-enterprise), which, structurally, looks something like this – in an all-too-literal sense, back-to-front and upside-down:

Which can be highly ‘profitable’ in a monetary-only sense in the short-term – but is guaranteed to cause failure, and even full-on disaster, in the longer-term. It also actively enables the disenfranchisement of all stakeholder-groups other than the putative ‘owners’.

To be blunt, it’s more accurately described as ‘a machine for legalised theft’ – especially life-theft – and often on a truly vast scale. Which is not a good or viable basis for either an enterprise or an economics, is it?

Which is why I argue that, as enterprise-architects, we need to challenge its horrendous built-in delusions – preferably before it kills us all…

OK, I see where you’re coming from, but I still think you’re acting like Zumbach the Tailor.

It’s not a “term hijack” when an entire culture redefines a word. You may take personal offense at the way the meaning of the word has evolved, but it happens all the time. Witness, for example, the misuse of “infer” to mean “imply” that has become so widespread as to have effectively redefined the word. “Profit” may have meant what you want it to mean in biblical times, but such usage today is legitimately characterized as archaic. Regardless, the fact is that your campaign to use the word the way you want to is unlikely to prevail. Again, you are free to do so, but no matter how frequently you remind people of what you want the word to mean, the simple fact is that most people are going to interpret it the way most people already do. “Profit” is not a term of art for enterprise architecture, it is a word in common usage and one that has a meaning similar to that common usage as a term of art in other disciplines.

That’s all I’ve been trying to say. You’re tilting at windmills on this, and you’re free to do so, but I don’t expect you to be successful in changing the way most people think about profit.

You go on to say:

“This brings us back to a point that you hadn’t responded to as yet,”

One thing at a time…

“namely that ‘profit’ is not a member of the same set as ‘goal, purpose, intent, outcome’. If you try to treat it as an instance of that same set, then yes, you’re going to fall straight into the kind of circularities I warned about above,”

Yet somehow I manage to avoid falling into these dreaded circularities.

“because they are fundamentally different.”

From a Zumbachian perspective, perhaps.

“Profit – and especially monetary-profit – is a side-effect of achieving a goal or suchlike”

A side effect? Most side effects are to be ignored unless noxious, in which case they are to be mitigated or eliminated.

I think for most businesses, profit is not a “side effect” of some other intended outcome. It is a necessary adjunct. The achievement of the desired outcome without the concomitant achievement of monetary profit is usually considered failure. Considerable effort is usually expended ensuring that monetary profit does indeed occur, and only a fool imagines that this happens without design. So yes, I suppose in some strict sense monetary profit is a “side effect” of something else happening, but that something else is usually very carefully designed specifically to produce profit.

This is what I meant by “sole purpose” being a bogus concept.

You are certainly free to think of monetary profit as socially undesirable, but I am wary of building that idea into a concept of enterprise architecture, or framing enterprise architecture as a discipline in a way that takes this position as axiomatic. And before you write me off as a capitalist pig,

consider that I can make such a statement without implying anything at all about my position on profit.

If you’re saying that “benefit” is a side effect of some other outcome, I agree with you; that’s in fact the central message of my comment. As I said earlier, “value” or “benefit” is a perspective-dependent property of an outcome. What’s more, it may change over time. That’s why a concept of enterprise architecture being driven by “profit” or “benefit” or “value” is build on a foundation of quicksand. The thing that is less perspective-dependent is the set of desired outcomes of an enterprise (typically realized through the activities of one or more organizations). Value or benefit may shape the nature of these desired outcomes, but unlike outcomes, these are things that really exist only as people’s feelings.

len.

Yeah, okay, it’s clear we’re talking at almost complete cross-purposes here: I don’t feel heard, at all, and I suspect you may feel the same about me. The key point, for me, is that whatever term we might choose, we need some term to describe these concerns: and if there are major term-hijacks in place – just as with IT-centrism and ‘enterprise’-architecture – then that leaves us dangerously stranded. To me what you’ve said above smacks of what the NLP folks describe as ‘arguing for your limitations’: yet if that’s the way you’d prefer to see it, that’s the way you’d prefer to see it – though I admit I could do without the repeated ‘Zumbach’ putdowns… (Sigh…)

I’m really disappointed that you’ve taken this tack, that (to my mind) you choose to constrain the views to such a narrow and closed perspective, and – to be blunt – seemingly choose to mock me instead, rather than actually looking at what I’ve said, and grasping what it actually implies, at a much larger scope and scale than mere commercial ‘stuff’. But again, that is your choice, not mine.

For what it’s worth, I’m actually not that interested in businesses per se for this piece. What I am interested in is identifying principles that apply to all types of enterprise, at every scale: which is not – as you seem to dismiss it – a Zumbach folly, but a necessary exercise in exploration of how fractal systems actually work. One of the tests for the validity of those principles would, yes, be how well they apply in commercial organisations (so-called ‘for-profit organisations’): but if we were to constrain it solely to that minutely-narrow subset of organisations and enterprises, we would be missing the main value of that exercise.

In exactly the same way that IT-centric ‘EA’ was and is a largely-pointless dead-end, focusing a larger-scope ‘EA’ solely on the money-only ‘for-profit’ subset of organisations is likewise a largely-pointless dead-end. To be blunt, we have far bigger fish to fry than those time-wasting energy-sinks, and not much time in which to do it. Mock me if you will: but recent-history has already proved that I was right about the limitations of IT-centrism, and I think you’ll discover in the longer-term that I’m just as right about this one too. Obviously you don’t think so right now: but, once again, that is your prerogative, of course – I do acknowledge that.

But yeah, disappointed…

Best leave it at that for now, I suspect?

You are clearly not hearing what I am saying. This last comment makes no sense at all to me, whatever you are reading into my words is nothing like what I am thinking as I write them.

You write:

“focusing a larger-scope ‘EA’ solely on the money-only ‘for-profit’ subset of organisations is likewise a largely-pointless dead-end”

I can’t believe that, after all we have talked about over the past several years, this is what you think I believe.

“Obviously you don’t think so right now: but, once again, that is your prerogative, of course – I do acknowledge that.”

You are so wrong in concluding this that I simply don’t know how to proceed.

And for what it’s worth, I am not mocking you.

len.

Len – again, thank you for your persistence, tolerance, whatever.

“…that I simply don’t known how to proceed.”

Same here. I don’t know what’s (not) going on here between us this time, but from both sides this whole interaction has turned out as a tragedy of crossed-wires, misunderstandings, mis-hearings, mis-readings, misinterpretation and general miscommunication. And everything we’ve each done to make it work better seems only to have made it worse.

It’s not been intentional on my part, and likewise I’m certain it’s not been so on yours. Just seems more that we’ve each started out on the wrong foot this time, with no way to disentangle the resultant mess.

Best to just respectfully write this one off, and start again from some other direction some other time?

No, I am not going to give up. I will keep trying because it is extremely important to me that we understand one another.

Boiled down to its essence, my original comment tried to make three points:

1) It is my opinion that the use of the word “profit” to denote a generalized concept of profit is likely to result in confusion and misunderstanding because of the connotational baggage the word now carries. It might be easier to make your point if you were to use a different word to denote this generalized concept.

2) It is my opinion that this generalized notion of profit is a kind of outcome that may be sought by the stakeholders of an enterprise; i.e., there are other outcomes besides “profit” (for any meaning of the word “profit” other than “outcome”) that may be sought by enterprise stakeholders, and that I think that outcomes, rather than the value stakeholders ascribe to these outcomes, provide a more stable basis for developing an architecture.

3) A single enterprise may (and in my opinion usually does)pursue multiple outcomes. We may refer to this set of desired outcomes as “the” desired outcome of the enterprise, but the use of the collective noun does not imply atomicity. Outcome in the most general sense may include observance of and adherence to a specific set of constraints on the way other outcomes may be achieved. I.e., the question “did you follow these rules?” is a form of “did you achieve this outcome?”.

Unstated, but assumed on my part, were the following:

1a) This observation about the risk of using the word “profit” to denote some generalized concept of profit is not a criticism in any respect of such a generalized concept.

1b) This observation neither says nor implies anything about the role of profit in enterprises or organizations.

1c) I agree that monetary profit is a poor metric for judging the success of an enterprise, and that many enterprises, and thus the organizations that realize them, pursue other outcomes besides monetary profit. For the moment, please resist the urge to insist that profit is not an outcome.

1d) Organizations and enterprises are different kinds of things, and the relationship between organizations and enterprises is many to many. An organization is typically the means by which an enterprise is realized.

1e) This observation about the use of the word “profit” neither says nor implies anything about the scope of applicability of “enterprise” or “organization”.

2a) The value that stakeholders ascribe to an outcome must be understood by an enterprise architect because there may be alternative outcomes that do a better job of delivering the desired value, and it is the responsibility of the architect to consider these alternatives. However, “value” is not tangible in the sense that an outcome is. What the enterprise, as an undertaking, and the organization(s) realizing the enterprise, deliver is outcomes, and various stakeholders will perceive these outcomes to have perspective-dependent value to them. It is because of this perspective-dependent nature of the value of clearly defined outcomes that I believe that an architecture should be shaped by outcomes. The same outcomes may have different values to different stakeholders.

2b) One of the most difficult challenges an architect faces is achieving stakeholder consensus. It is hard enough to achieve consensus on desired outcomes; it is much harder to achieve consensus on the value of these outcomes.

2c) This observation about the relationship between outcomes and the value of outcomes does not in any way minimize or denigrate the importance of value. It is a practical consideration about what is the more tractable and stable first order driver of an architecture.

3a) It is in this sense that I consider “profit” whether in the sense of “monetary profit” or more generally some form of “benefit” to be a kind of outcome. Note that consistent with observation 2 I consider “benefit” to be different from “value”. An outcome can be anything the enterprise (and thus the organization(s) that realize(s) the enterprise) is designed to achieve.

3b) In a very real sense, the system-nature of an enterprise means that all outcomes are “side-effects” of all other outcomes. A proper architecture of the enterprise almost necessitates that they be delivered as an integrated package, though a flawed architecture, or a flawed implementation of a proper architecture, will likely deliver a flawed “package” of outcomes.

Does this help?

len.

Some afterthoughts:

Re 1e): scope of applicability is not just about size, it is also about the nature of the enterprise’s undertaking.

Re 2b): It may, in my opinion, be neither necessary nor desirable to achieve stakeholder consensus about the value of outcomes. Note that “may not” does not mean “must not”.

Re 3a): Outcomes may be discrete or continuous. An outcome may be anything that the enterprise (and the organization(s) that realize(s) the enterprise) has been architected (and thus designed) to be, have (as a property) or do.

len.

Many thanks, Len – yes, it does help.

And yes, this is going to need a lot of very careful thought and… well, you know, kinda hyper-cautious, hyper-precise, all the ‘t’s dotted and the ‘i’s crossed, all that kind of stuff? 🙂 And with that level of care and sheer head-banging, it may well take me at least a couple days to pin it all down…

Because of that, I’ll need to split this into four parts, posted as four separate comments – this intro, and then one for each of your three themes above: the word ‘profit’; profit as outcome; and enterprise and multiple outcomes. (As I go through those three themes, I’ll also include into the exploration the add-on notes from your comment immediately above.)

—

Intro

One of the challenges here is clarity on the audience for this discussion.

Personally, I tend to assume that, unless I indicate otherwise, my main audience is people who work either with various forms of enterprise-architecture, or with ‘architecture’-like themes (e.g. big-picture strategy, or – closer to implementation-contexts – themes such as devops) typically at or close to an enterprise-wide scope. The language I would use in that type of context is both much more general (concerning ‘universals’ etc), yet also demanding much more precision, than the kind of language I would use for, say, a mainstream presentation, or in talking with executives and software-designers.

On this blog, I usually don’t write for a mainstream business audience. One of the outcomes ( 🙂 ) of that is that I’m usually much more picky and pedantic in the way I use terms than perhaps many (most?) people might expect. If they then try to translate what I’ve said as if it were as messy and careless as they tend to use terms, then yeah, it’s not going to make sense to them. But if they choose to do that – having been explicitly told that ‘professional-type’ language is in use, in exactly the same way as in other disciplines – then that’s in no way my fault, is it? In which case it is not fair that people then blame me for their failure to understand what I’ve said.

Just as a simple example, the casual blurring of function versus process versus capability versus service etc that’s endemic in mainstream business really doesn’t matter to them – they know what they’re talking about (well, sort-of, some of the time, anyway). But it drives architects and others crazy, because we need to be precise about what we’re doing as we move towards implementation. For our purposes, we need to be much more precise, with explicit, clearly-identifiable and, often, recursive definitions that make sense and essentially remain the same in every context – otherwise we have no means to describe key architectural concerns such as substitutability, trade-offs and the like.

Going the other way, terms such as ‘charge’, ‘spin’, ‘charm’ and ‘strangeness’ have very specific meanings in nuclear physics – and anyone who wants to play in that space hard darn well better learn those terms, and why they’re used in that way. And also not blur those context-specific meanings with the more everyday colloquial ones – otherwise the conversation will quickly lose any sense at all.

So right here, right now, for this purpose of this comment-stream, the way I understand what’s happened is a kind of jumping-around between colloquial and precise usage of key terms. In part this has been forced on us by other people’s blurry and incorrect usage of terms – in particular, in the ‘for-profit’ versus ‘not-for-profit’ split which is what this post initially aimed to address. But it doesn’t help…

So in what follows, I’m going to be hyper-pedantic, explaining my reasoning every step of the way, explaining why I use particular terms, and why I use them in that way and for that purpose. The functional logic of the argument builds up from those usages – and the argument will only make sense with those usages. If you try to force-fit any other usage into the same argument, it will not make sense – or, at best, will make a scrambled and dysfunctional sort-of sense that largely misses the key points and, sometimes, some very subtle yet utterly crucial nuances that I’m trying to explain.

In short, if anyone insists on enforcing colloquial or other (mis)usages where they don’t apply, don’t blame me if it doesn’t make sense…

With that said, let’s move on to your specific points.

First, I think you have made this into something much bigger than I ever intended.

You start with:

“One of the challenges here is clarity on the audience for this discussion”

I don’t see this as a challenge at all, and the simple points (not “themes” as you call them) I was trying to make are (in my opinion) independent of the audience.

I do understand that sometimes it is appropriate to adopt Humpty Dumpty’s stance:

“I don’t know what you mean by ‘glory,’ ” Alice said.

Humpty Dumpty smiled contemptuously. “Of course you don’t — till I tell you. I meant ‘there’s a nice knock-down argument for you!’ ”

“But ‘glory’ doesn’t mean ‘a nice knock-down argument’,” Alice objected.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said, in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

As you say:

“But if they choose to do that – having been explicitly told that ‘professional-type’ language is in use, in exactly the same way as in other disciplines – then that’s in no way my fault, is it? In which case it is not fair that people then blame me for their failure to understand what I’ve said.”

I have to admit, this sounds a bit Zumbachian to me — “I have perfectly crafted the suit, and if it does not fit it is because you are not wearing it properly”. I learned a long time ago that blaming the listener for their failure to understand me was not an effective way to improve my ability to communicate my ideas. And that was the essence of my observation, and that is all it was, an observation. You can insist that people understand that you are using a word in a particular way, but that doesn’t guarantee that they will. They likelihood that they can or will do so depends on the particular word and how you are using it.

I also doubt that listeners deliberately “choose” to ignore your insistence that they understand you a certain way. More likely they find it difficult because you are asking them to understand a word in a way that is different from the way they have always understood it. It is like telling a right-handed person, “you must do this with your left hand, or else it will not work”. This may be true, but it doesn’t make it easy.

That is all I was trying to say. You can use words any way you like, but if you want to successfully communicate, it helps to take account of how people are likely to hear you. A mathematician who expresses a proof in a personal notation, no matter how well explained it might be, creates a barrier to other mathematicians understanding the proof. It doesn’t matter if the proof is correct, or how significant it is, it is simply more difficult to understand if expressed certain ways rather than certain other ways.

I have tried repeatedly to make this simple observation clear to you. That’s all I’m trying to say.

You close with:

“In short, if anyone insists on enforcing colloquial or other (mis)usages where they don’t apply, don’t blame me if it doesn’t make sense…”

Once again, as clearly as I can express it, nobody is (certainly I am not) insisting that you adopt colloquial usage. For the umpteenth time, I am simply saying that words that are in common use have connotations that can be difficult to “forget” in any context. I am not saying that you must only use “profit” a certain way, but rather that if you want to denote a concept importantly different from the nearly universal current understanding of the meaning of the word, you might be more successful using a different word. You have made it clear that you consider this an unacceptable imposition on your prerogatives. OK. Just don’t be surprised when people misunderstand you. And blaming them for misunderstanding you will not help them understand you.

My response to much of what follows will be variations on this “theme”. I don’t want to sound dismissive, because much of what follows is valuable, but a lot of it is irrelevant to the simple points I was trying to make.

In particular, the unstated assumptions 1a) through 1e) are also largely irrelevant to the simple point I was trying to make. I made them explicit simply because you somehow concluded that I believed otherwise, though I cannot find anything in what I did say that implies that I believe otherwise, and I have repeatedly and consistently expressed these positions in other conversations we have had.

More later.

len.

Usage of the word ‘profit’

@Len: “It is my opinion that the use of the word “profit” to denote a generalized concept of profit is likely to result in confusion and misunderstanding because of the connotational baggage the word now carries. It might be easier to make your point if you were to use a different word to denote this generalized concept.”

To explain this, I’ll use the first of those two Enterprise Canvas diagrams I posted in that comment earlier above:

Before I go into the detail (your points 1a to 1e), two points I need to emphasise:

x) The word ‘profit’ is somewhat forced on us by the ‘for-profit’ versus ‘not-for-profit’ distinction that’s being explored in the main part of the post. As a result, we need to be especially careful to be clear as to whether we’re using a monetary-only meaning of ‘profit’, or a broader sense of ‘extracted-value’ (see next point) – of which only the latter is meaningful when we need to generalise the respective concepts to an ‘any type of enterprise’ context (i.e. ‘for-profit’ and ‘not-for-profit’ and ‘government’, etc, etc).

y) In terms of the Enterprise Canvas diagram above (used for illustrative purposes only – please keep Zumbach at bay, if you would? 😐 ), what I’m focussing on is the service’s relationships with its stakeholders in the roles of ‘investor’ and ‘beneficiary’, and the respective value-flows described as ‘investment’ and ‘dividend’. (In this context, ‘dividend’ is arguably an even more ‘hijacked’ term than ‘profit’… – but that and ‘profit’ seem to be the only terms available to me for this purpose right now.) Leaving aside ‘investment’ for a moment – other than that in the ‘for-profit organisation’ case, monetary-investment is often deemed to confer exclusive ‘ownership-rights’ over the organisation – the ‘dividend’ flow represents extracted-value: a proportion of value-return from the service-consumer transformed, extracted and delivered to the beneficiary. Crucially, these are not the same as the ‘horizontal’ value-flows across the service, nor are they the same as the ‘why’-values that underpin the relationships between the service and all of its diverse and disparate stakeholder-groups.

@Len: “1a) This observation about the risk of using the word “profit” to denote some generalized concept of profit is not a criticism in any respect of such a generalized concept.”

From what you’ve said elsewhere, there is a need for a clear term that denotes that ‘generalised concept of profit’ – as indicated clearly by the point that if a ‘not-for-profit organisation’ does not return some kind of value to its non-transacting stakeholders, then why would it exist? Historically, the word ‘profit’ did indeed hold that generalised meaning until relatively recently, and in many contexts still does. For colloquial purposes, we need to acknowledge the current common tendency to presume that ‘profit’, and therefore the risks of misunderstanding if we allow people to apply that scope-narrowing term-hijack when we’re describing a broader context. But for architectural purposes, there really isn’t any alternative term (in English, anyway) that precisely describes that ‘extracted-value flow’ relationship between service and beneficiary.

@Len: “1b) This observation neither says nor implies anything about the role of profit in enterprises or organizations.”

This post explicitly does address “the role of profit in enterprises or organisations”, and in their various relationships with their stakeholder-groups. That’s the whole point of this post.

@Len: “1c) I agree that monetary profit is a poor metric for judging the success of an enterprise, and that many enterprises, and thus the organizations that realize them, pursue other outcomes besides monetary profit. For the moment, please resist the urge to insist that profit is not an outcome.”

On the first part of this, yes, we’re agreed. The catch is that we need some means – some generalised means – to describe, first, the nature and metric of ‘success’ both for an enterprise and for an organisation in relation to an enterprise (your point 1d, shortly), and second, the return of extracted-value to the service’s stakeholders. These are not the same things – whereas treating “monetary profit [as a] metric for judging the success of an enterprise” does treat them as the same. Disentangling the resultant mess is one of the architectural challenges we frequently face at present when working at a whole-of-enterprise scope and scale.

On the second part, no, I’m sorry, but I must insist that profit is not ‘an outcome’: to be pedantic – and we need to be pedantic here – it must be seen as a by-product of an outcome, not an outcome in its own right. Or, if you absolutely must insist that it ‘is’ an outcome, then it’s essential to acknowledge it as an outcome of a fundamentally different type than either the outcomes in the ‘horizontal’ value-flow or the values-oriented ‘success-outcomes’ of the enterprise as a whole. (Again, for illustrative purposes, the Enterprise Canvas diagram above does help to clarify these distinctions.)

Monetary (or other) profit is a ‘desired outcome’ (if you insist) of specific beneficiary-stakeholders. The moment that it’s taken to be the desired-outcome of the organisation (or, worse, the shared-enterprise), we’d be set on the path to failure – because it’s not the outcomes that we need in order to guide the operation of the organisation and its services, which operate in a literally different plane. (Hence why I’d argue it’s best to view monetary or other ‘extracted-value’ is a ‘by-product’ of those other service / organisation / enterprise outcomes).

@Len: “1d) Organizations and enterprises are different kinds of things, and the relationship between organizations and enterprises is many to many. An organization is typically the means by which an enterprise is realized.”

Yeah, we mostly agree on this one. Yet there’s a kind of trick here that I suspect you may have missed, and hence setting up an argument that doesn’t actually exist. It’s a trick that I’d suggest should be specific to architects, but it provides a way out of the otherwise-impenetrable tangle that that many-to-many relationship creates, especially when we start to get into recursive relationships between organisations (organisation-includes/intersects-with-organisation) and between enterprises (enterprise with enterprise) as well.

The trick is this: we declare that an enterprise (in the sense of the term that we both agree on, distinct from ‘organisation’ etc) is always singular. An enterprise has one guiding vision, one set of guiding-values, which devolve to principles, and so on, recursively and all that. It’s a fudge: an assertion, for our purposes in architecture and the like.

In other words, I’m not claiming it as some supposed ‘absolute truth’ – don’t worry about that. But do note that all of the Enterprise Canvas material, about values versus value, service-relationships and all that, all devolve from and rely on that one assumption. To put it the other way round, if we don’t use that admittedly-arbitrary assertion, it soon becomes all but impossible to work out or describe what the heck is going on in the organisation/enterprise relationship. So yeah, in strict technical sense, it’s a fudge: but it’s a useful fudge. 🙂

Once we’ve accepted that assertion that ‘an enterprise is always singular’, then we can apply all those many-to-many relationships and so on. But not before: that’s crucial. Not for theory, but simply for sanity… 🙂

@Len: “1e) This observation about the use of the word “profit” neither says nor implies anything about the scope of applicability of “enterprise” or “organization”.” // “Re 1e): scope of applicability is not just about size, it is also about the nature of the enterprise’s undertaking.”

For the most part, agreed.

The catch is that in this context – so-called ‘for-profit’ versus ‘not-for-profit’ – the use of the word ‘profit’ supposedly does say and imply something about the scope, applicability and nature of the organisation(s) and/or its/their related enterprise(s). What this post asserts is that, to make sense of what’s actually going on in those contexts, we first do need to acknowledge that the colloquial-usage makes certain assumptions, which – to make it work – we need to deconstruct and generalise.

That’s about all for this one, really.

Profit as outcome

@Len: “2) It is my opinion that this generalized notion of profit is a kind of outcome that may be sought by the stakeholders of an enterprise; i.e., there are other outcomes besides “profit” (for any meaning of the word “profit” other than “outcome”) that may be sought by enterprise stakeholders, and that I think that outcomes, rather than the value stakeholders ascribe to these outcomes, provide a more stable basis for developing an architecture.”

I’ve dealt with much of this under ‘1c)’ in the previous reply-comment (“Usage of the word ‘profit'”). I’d add again that, for illustrative purposes the Enterprise Canvas frame provides a useful means to clarify some of the distinctions that are essential here.

@Len: “2a) The value that stakeholders ascribe to an outcome must be understood by an enterprise architect because there may be alternative outcomes that do a better job of delivering the desired value, and it is the responsibility of the architect to consider these alternatives. However, “value” is not tangible in the sense that an outcome is. What the enterprise, as an undertaking, and the organization(s) realizing the enterprise, deliver is outcomes, and various stakeholders will perceive these outcomes to have perspective-dependent value to them. It is because of this perspective-dependent nature of the value of clearly defined outcomes that I believe that an architecture should be shaped by outcomes. The same outcomes may have different values to different stakeholders.”

Again, my reply to ‘1c)’ should have covered much of this already, though I’ll add that I strongly agree re “The value that stakeholders ascribe to an outcome must be understood by an enterprise architect” and the rest of that sentence.

Where we may part company a bit is around the relationship between ‘value’ and ‘outcome’: in a viable service, its outcomes are always in context of the values of the respective shared-enterprise (i.e. the ‘vertical’ links through the service, in Enterprise Canvas).

This leads to some potentially-horrible nuances and pedantries around outcomes and value. The best way I can summarise it is that outcomes should, in principle, not be perspective-dependent – an outcome is simply an identifiable result of what happens. The desirability (or not) of an outcome – and hence its perceived ‘value’ – is perspective-dependent. If we treat the value and the outcome as the same thing – or worse, clutter up that mess with the further perspective-dependent mess of perceived ‘profit’ – then we’re not going to have any chance to make sense of what’s going on. This is another Tom’s Pedantries that really do matter here…

@Len: “2b) One of the most difficult challenges an architect faces is achieving stakeholder consensus. It is hard enough to achieve consensus on desired outcomes; it is much harder to achieve consensus on the value of these outcomes.” // “It may, in my opinion, be neither necessary nor desirable to achieve stakeholder consensus about the value of outcomes. Note that “may not” does not mean “must not”.”

As in your addendum there, I’d argue that we actually don’t need to achieve consensus about desired outcomes. We do need to achieve balance on outcomes, and some consensus on balance on perceived-value of returns from outcomes – but that’s not the same thing at all… 😐

On “‘may not’ does not mean ‘must not'”, I just wish some of the ‘profit=money’ crew would understand that point: many of them do seem to cling on to the notion that no balance is needed at all… 😐 (But yes, I know we agree on that point too.)

@Len: “2c) This observation about the relationship between outcomes and the value of outcomes does not in any way minimize or denigrate the importance of value. It is a practical consideration about what is the more tractable and stable first order driver of an architecture.”

I’m not sure here as to which you mean as the ‘more tractable and stable first order driver’?

If you mean ‘profit as outcome’ (in whatever way we might determine profit’), then no, I strongly disagree: it’s a by-product, an outcome of a whole slew of non-linear and non-transitive transforms, and cannot meaningfully be used as a driver at all.

But if you mean ‘values’, then yes, those are drivers – and usually easy to identify as such, as well. It can sometimes be tricky to identify appropriate success-metrics that link back to those values – all the problems with ‘targets’ and suchlike, as Simon Guilfoyle describes so well – but if we can do that properly, it works really well.

The key distinction is that values provide anchors for lead-indicators, whereas ‘profit’ and the like can at best only provide lag-indicators. Should be obvious just from that as to which is more appropriate and more stable as a driver for an architecture.

Okay, enough on that – move on to the last one.

Enterprise and multiple outcomes

@Len: “3) A single enterprise may (and in my opinion usually does)pursue multiple outcomes. We may refer to this set of desired outcomes as “the” desired outcome of the enterprise, but the use of the collective noun does not imply atomicity. Outcome in the most general sense may include observance of and adherence to a specific set of constraints on the way other outcomes may be achieved. I.e., the question “did you follow these rules?” is a form of “did you achieve this outcome?”.”

I’ll admit this is the response I have most difficulty with, for several reasons.

Re “A single enterprise may (and in my opinion usually does)pursue multiple outcomes”, I’ve partly answered this one in my response to your ‘1d)’ above. I don’t disagree that we can choose to look at it that way: my practical complaint is that if we allow that in modelling of enterprises, it soon becomes all but impossible to make any sense of what all the interdependencies are. It also really does make it way too easy to again get confused between ‘organisation’ and ‘enterprise’ – which is not a good idea, as we both know. Hence why I take a somewhat Gordian Knot approach to the whole thing, and arbitrarily define ‘an enterprise’ as ‘something that has a single vision-based purpose’. Outcomes then arise from an organisation’s contextualised response to that ‘vision’ or ‘promise’ – with, in practice, an effective synonym for that contextualised-response being the term ‘strategy’.