Keep the focus on the right market!

If enterprise architecture at present is perhaps too WEIRD and too WIRED, how would we describe current management models? And if they’re as mistaken and misfocused as enterprise-architecture still seems to be, what impact does that have on their organisations and enterprises?

This one’s come up from several different directions over the past few days, but perhaps particularly from this quote from Greg Satell’s recent Forbes article, ‘5 Business Secrets You Probably Never Thought Of:

Bob Sutton’s new book, Scaling Up Excellence, written with Huggy Rao, tells the story of a firm that sought to inspire greater cooperation and information sharing, while lessening emphasis on short term results. Yet when Sutton and Rao visited the company, they found that the firm’s top executives all had the company’s stock price as their screen savers.

Yeah, we see that a lot: no real surprises there. Yet if I were chairman of the board, I would fire the whole lot of them straight away – because that one fact alone would tell me that they weren’t doing their jobs properly – that their focus was on entirely the wrong place for the organisation’s real needs. Not just the wrong place – the wrong darn market!

The reason why is that, for guiding the actual operations of a company, the stock-price is perhaps the least-useful item of information there is. It’s not a lead-indicator, but a lag-indicator – a metric of outcomes, not inputs or actions – and in many ways one of the most ‘laggy’ of lag-indicators at that. It may be of interest to the stock-market, of course – but for the company, and for the executives who are supposed to be guiding the company, it tells them almost nothing at all. Nothing they can use, to guide the company forward into the future.

And if – as ‘the market’ no doubt tells them – what they should focus on is financial-performance on behalf of ‘the owners’, they’re still going at it the wrong way round, because of a crucial systems-type paradox: in order to achieve best success in something, keep the focus on everything except that ‘something’. We might describe this as the Runner’s Paradox, because a runner who wants to win a race needs to focus, for most of the time, on everything except the race. Focus on diet, for example; breathing; balance; stretching; mental state; positioning; poise; and much, much more. Even on the race day, and perhaps even more during the race, the runner still need to keep the focus on everything except the race itself. Only after the race does the race itself become significant for the runner – and by then it’s already too late to do anything about it. The same applies to companies too…

So where does it all go so wrong?

Why is the focus so often completely on the wrong place?

And if it is the wrong place – the wrong market – then what’s the right market to focus on?

Okay, yes, I’ve already written a lot about various aspects of this on this blog. Some previous examples (in no particular order) include:

- Money, price and value in enterprise-architecture

- Money as the ‘information-shavings’ of the economy’

- Why Economics 101 is bad for enterprise-architecture

- Quality-systems and enterprise-architecture

- Business Model Canvas beyond startups: Part 1

- Every organisation is ‘for-profit’

- Costs of acquisition, retention and de-acquisition

- Anticlients are antibodies

- Yet more on ‘No jobs for generalists’, Part 3c: The impact of ‘the owners’

- A problem of possession

- Services, customers and citizens

Given that I have already written a lot about it, I won’t go over all of that again here. 🙂 For here, we’ll stick to just that one question: if the stock-price isn’t much use, what should management focus on, from an enterprise-architecture perspective?

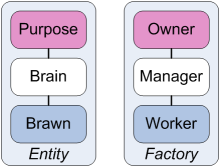

Probably the simplest place to start is the neo-feudalism that underpins Taylorism and much of the associated business-law – the classic ‘one-way hierarchy’ that’s become so deeply embedded in business-consciousness that it’s often assumed to be ‘the natural order of things’:

Which leads, in turn, to this type of service-oriented concept of how an organisation works and how it relates with its business-context, in its role as ‘a machine for making money’ for its nominal ‘owners’:

This structure is fractal and recursive – hence the silos and hierarchies of business-services, and the hierarchies and organisation-structures of management, from line-managers to middle-managers to top-executives, at the supposed ‘top’ of the hierarchy-tree. Since all the other managers are kind of ‘buried’ deeper and deeper within the hierarchy-tree, the top-executives are only ones who have a primary relationship with ‘the owners’: and hence – in a stock-market context, where relationships with stockholder ‘owners’ are usually somewhat distant and ‘hands-off’ – the apparent importance of the stock-price.

On the surface, it looks like it would work well – from the perspective of ‘the owners’ and the executives, at any rate. And back about a century ago – maybe even half a century ago – it did work well for those specific stakeholders. But the catch is that, in practice, it can only be made to sort-of appear to work well in a very specific special-case:

- monopoly or near-monopoly business-context

- low rates of change in product, service, market and/or business-context

- little to no risk of technological or other disruption

- legal-system providing active support for neo-feudalism

In present-day business-contexts, organisations’ ability to hold on to those special-case conditions is fading fast. Even the old legal-system of exclusive ‘rights of possession’ for ‘the owners’ is coming under challenge, not least because it’s becoming more evident that any assertion of ‘possession of all assets’ in a knowledge-based organisations – where the primary assets are the knowledge and skills of the organisation’s employees – is all but tantamount to assertion of ‘right’ to slavery. That kind of assertion is not a wise idea…

For anything other than that one type of special-case, that ‘investor-first’ notion of business-structure is likely to prove bizarrely back-to-front and upside-down, compared to what’s actually needed in the kind of real-world conditions we face in current business-contexts:

- active disruption or fragility of monopoly-positions

- high rates of change in product, service, market and business-context

- high risk of technological or other disruptions, in almost all industries

- increasing legal and social pressures to disrupt oligarchic neo-feudalism and the ‘rights’ to avoid social-responsibilities (such as via externalities) that underpin it

The distortions that that classic Taylorist-type model imposes on all of the organisation’s other relationships become so extreme that its ability to cope with the types and rates of change now typical in most markets, products, services and technologies can easily become stretched beyond viability.

To make the model work – and, in particular, to enable it to cope with rapid changes in market, in technologies and in overall business-context – we in effect need to turn the whole frame the other way up.

The first part of this is to break away from the obsession with ‘shareholder-value’ – “the dumbest idea in the world”, as Jack Welch once put it:

On the face of it, shareholder value is the dumbest idea in the world. The idea that shareholder value is a strategy is insane. It is the product of your combined efforts – from the management to the employees. Shareholder value is a result, not a strategy. … Your main constituencies are your employees, your customers and your products.

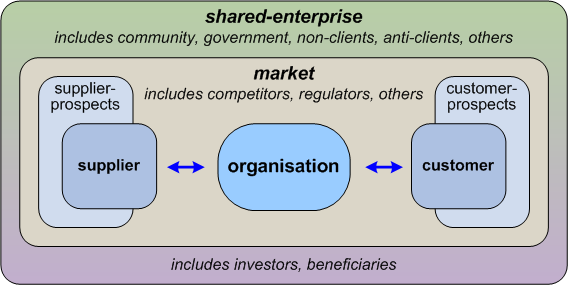

Hence, at the very least, the executives need to focus less on the stock-market, and instead focus much more on the market that their customers and suppliers are in – not least because it’s the only source of financial-returns and the like, that can ultimately be extracted on behalf of the ‘owners’ as ‘shareholder-value’:

Yet even this ‘the market’ is still not the most important market that executives need to focus on. The business-market itself exists only in context of an even larger market, a shared-enterprise that accretes around a kind of shared-story:

Stock-holders and other financial-investors are merely one small subset with this overall shared-enterprise – and, from an enterprise perspective, need to be viewed and understood solely as equal peers with all of the other stakeholders in this more ‘outward’ market.

Crucially, the shared-enterprise determines and defines what value is, within that overall enterprise and its markets – of which money-based ‘shareholder-value’ is, again, only one amongst many. We ignore this fact at our peril… Even if they’re supposedly forced to defend all decisions in terms of ROI for ‘shareholder-value’ and suchlike, executives need to engage with these supposedly ‘external’ stakeholders and their much broader range of values than money alone.

And the key point here, perhaps, is that we need to pay attention to the Runner’s Paradox: we deliver best ‘shareholder-value’ by paying attention first to everything except ‘shareholder-value’. Johnson & Johnson summarised it well in their classic business-Credo:

Service to customers comes first…

Service to employees comes second…

Service to management comes third…

Service to the communities comes fourth…

Service to stockholders comes last.

In current practice I’d suggest a key tweak to that, because, as above, it’s advisable to consider that ‘the communities’ – the shared-enterprise – actually come first, before all others. But essentially that Credo is about the right way to view it: the way that works.

Which, ultimately, brings us to the kind of view of business-structure – organisation-as-a-service, a service to all stakeholders in the overall shared-enterprise – that’s encapsulated in the Enterprise Canvas framework:

It is, as we’ll note, the other way up to the Taylorist view: oriented always to the future, rather than the past – and with money and the like as an outcome, rather than the first and only driver. Also, crucially, values are not subsumed into ‘management’ – as in the Taylorist model – but are acknowledged as necessarily somewhat orthogonal, such that management too is subject to those values. Coordination is likewise not subsumed into management, making it possible to retain the efficiency-advantages of silos, yet also bridge across them as and wherever that may be required.

In Enterprise Canvas, the priorisation of the markets aligns exactly with the dictates of the Runner’s Paradox:

- values – enterprise-market

- value-flow – business-market

- investment and return – stock-market

The stock-market and other investors are, in essence, viewed solely as providers of finance and financial-services – with no inherent difference in stakeholder-relationship from that of provision of any other type of service. In other words, provision of finance does not and should imply automatic ‘ownership rights’ over and above every other stakeholder – especially as such purported ‘ownership’ via the stock-market may, in these times of high-frequency trading and the like, may actually last only for milliseconds or less.

By contrast, in the upside-down Taylorist model, the financial-investors are usually deemed to be the only ‘owners’, and certainly the only beneficiaries. In terms of its priorities of attention for the different markets:

- the stock-market always comes first

- the business-market comes a grudging second, as a necessary source from which to extract revenue

- the shared-enterprise is deemed to be irrelevant, and ignored or silenced as much as possible

The (non)-relationship with the shared-enterprise is perhaps best summarised in the infamous assertion, often attributed to Milton Friedman, that “the business of business is business” – ‘making money’ for stockholders, with no other driver or responsibility either acknowledged or permitted. Joel Makower comments, in a 2006 article, ‘Milton Friedman and the Social Responsibility of Business‘:

In a 1970 ‘Times‘ magazine article, the economist Milton Friedman argued that businesses’ sole purpose is to generate profit for shareholders. Moreover, he maintained, companies that did adopt “responsible” attitudes would be faced with more binding constraints than companies that did not, rendering them less competitive.

Yet as Makower warns:

We know better now. For example, we understand that ignoring environmental and social issues can be bad for business. Companies that pollute their local communities risk poisoning their customers. Ignoring the state of the local school system risks depleting the pool of qualified workers. Abusing workers risks higher turnover and training costs, not to mention greater difficulty attracting the most qualified candidates.

Perhaps most important is that, as business-writer Charles Handy warned in his classic RSA lecture ‘What is a company for?‘, the organisation is ultimately dependent on the shared-enterprise, and society as a whole, for what he described as the organisation’s ‘social licence to operate’. Without that societal approval, there is no business – and without the business, no profits for its stockholder ‘owners’. As society itself undergoes major change, Taylorists and other neo-feudalist executives might well be wise to take more note of that one rather important fact.

In short, for best business success, and even for best returns to shareholders, keep the focus on the right market! – the enterprise, and the business. Not the wrong one – the stock-market.

Simple as that, really.

Implications for enterprise-architecture

For enterprise-architects, this one is going to be tricky. Obviously.

And not least because most enterprise-architects at present still work within Taylorist or similarly neo-feudal organisations, where one false move or misplaced comment can lead to loss of job, or worse.

Very tricky, in fact…

Yet it’s not something we can afford to ignore: because if the executives focus too much on the short-term share-price, they are going to drive the organisation over a cliff, sooner or later – at which point the architects’ jobs would be lost then anyway.

And it is part of our task as enterprise-architects – even for those working solely on ‘the architecture of the enterprise-IT’ – to be fully aware of and support how the organisation works in a systemic sense, as a whole: which means that, ultimately, all of our work must support an enterprise-first approach, whether or not that’s what executives say they want.

In many cases, we’ll probably have to do it ‘by stealth’. For example, we might build ‘executive dashboards’ that might show the stock-price front-and-centre as required, but tag it solely as a lag-indicator; and instead emphasise the lead-indicators – from the shared-enterprise and the business-market – that enable practical decisions to be made, and that will ultimately show up as factors in the short-term fluctuations of the stock-price.

For the lead-indicators from the business-market, the key – as Jack Welch also put it – is “execution, execution, execution”. We need real-world performance-metrics that indicate the status of themes that can be adjusted at executive level: as Simon Guilfoyle warns, performance against predefined targets is a classic example of exactly what not to use for this…

For lead-indicators from the enterprise, the real key concern is current sentiment, and other indicators of the organisation’s ‘social licence to operate’. Social-media tracking of anticlient activity is probably a key example of this; also real (not ‘laundered’!) indicators and outliers customer-service activity, if the risk of the organisation’s own expensive equivalent of ‘United Breaks Guitars‘ is to be avoided.

But what if your executives dismiss all of this as ‘irrelevant’? Well, one option is to gently remind them about the other stock-market – where animals are rounded up and sold for slaughter? That metaphor might just help to sober them up enough to see that that headlong rush into the stock-market might not always be a wise idea…! 🙂

Over to you for comment, anyway?

Leave a Reply