RBPEA: An anticlient’s tale

How does someone become an anticlient – a person who’s committed to the same aims of the same shared-enterprise, but vehemently disagrees with how you or your organisation are acting within it? And, since anticlient-actions can actually kill the entire organisation, what can we do about it, to mitigate against those impacts?

To most people, anticlients are most often seen as a ‘problem’ – something to be silenced, shut down, eradicated if at all possible. In reality, though, we need to listen to our anticlients – they’re trying to tell us something important, that we need to hear before it’s too late. The simplest analogy to explain this is that anticlients are antibodies – the immune-system of the shared-enterprise within which our organisation operates. If we don’t listen to what that immune-system is telling us, we’re likely to get ill – metaphorically speaking – or worse. If the immune-reaction is strong enough, or virulent enough, and we keep on trying to ignore it, pretend it isn’t happening? – well, let’s just say that that’d be yet another all-too-suicidal example of Not A Good Idea…

To make sense of this, though, we first need to understand how shared-enterprises actually operate. There’s a common delusion, especially in business, that ‘the organisation is the enterprise’ – which it isn’t – or at least that everything in the shared-enterprise revolves around the organisation – which it doesn’t. The simplest way to describe this is that the organisation is a ‘how’, whereas the shared-enterprise is the ‘why’ – the story – that brings everyone together. In visual form, the relationships look somewhat like this:

The crucial point here is that – as you can see from that diagram – an organisation’s anticlients aren’t in its direct scope of engagement, its market: they’re out beyond that inner space, either because they’ve always been there, or because they’ve moved out of connection with the organisation. Yet even though they’re outside of that direct connection-space, they can bring huge indirect influence – or, in some cases, direct influence – to bear upon the organisation, ‘from the outside’. One way or another, anticlients can destroy an organisation’s ‘social licence to operate‘ (to use Charles Handy‘s term) – and with it, the organisation’s business as a whole.

The core concept that underpins an anticlient-relationship is what we might summarise as ‘right idea, wrong implementation‘: the anticlient believes strongly in the underlying-story that defines that shared-enterprise, but also strongly feels and/or believes that the way organisation is relating to that shared-enterprise is ‘wrong’, inappropriate, misleading or whatever, or that the organisation has ‘betrayed’ their promise to its clients or others.

One of the points to note here is that anticlients focus more on the shared-enterprise story, and the organisation’s purported promise in relation to that story – literally, its value-proposition, what it promises to do in order to deliver value into that story. If the organisation’s intent or actions are perceived as ‘unfair’ to certain stakeholders or to the story as a whole, that’s when an anticlient-type reaction gets triggered off. Every time we fail to address those reactions, properly, or at all, we further feed the tensions on a kurtosis-risk that could explode at any moment, seemingly ‘without warning’ – especially when an entire industry is feeding that risk, in a process I call ‘pass the grenade‘. Again, these are risks that, from the organisation’s perspective, can be right out there in the most serious category of Not A Good Idea… – and yet scarily-few people in business and elsewhere seem able to recognise that these risks even exist. Worrying, to say the least…

In practice, there are two significantly-different types of anticlient-relationships. The first is what we might call inherent-anticlients – people who would always be anticlients to the organisation’s aims or story in relation to the shared-enterprise. For example, if your business is about doing oil-exploration and oil-exploitation in the Amazon, you are inherently going to have environmentalists and indigenous-peoples as anticlients: it goes with the territory, so to speak. The disagreement with the organisation and its promise is often quite conceptual – a clash of ideas or ideologies – and typically transits quite quickly through the following phases:

- Finding, assessing and rejecting the promise

- Anger and reaction

- Commitment to counter-activism

It eventually settles down into the all-too-visible clashes of action and reaction both ways that we all know, and probably don’t love, from the TV-news and elsewhere. However, it can be possible in some cases to look for and find common-ground enough for a mutual ‘power-with’: Walmart’s engagement with sustainability-activists is one of the perhaps better-known success-stories of this type. In a sense, the relationship was down right from the start, so the only way forward is up.

The other type of anticlients are what we might call betrayal-anticlients – people who had previously engaged with the organisation and its promise, but now feel that (usually) they themselves and that promise have both been betrayed. As such, the disagreement with the organisation and its promise is often quite literally visceral, far less about ideas than about feelings – so much so that the typical attempts by organisations to ‘tackle it rationally’ merely make things worse. To make sense of this, we need to remember that, in these types of contexts, feelings are facts, whereas interpretations and rationalisations about those feelings are not facts – not the other way round, as way too many people still seem to think… The engagement-pattern is significantly different from that of inherent-anticlients, and typically goes through the following phases over a longer period of time – weeks, months, years, even decades or more:

- Searching for the promise

- Finding oneself in the promise

- Commitment to the promise

- Self-doubt and self-blame

- Realisation and disillusionment

- Anger and reaction

- Futility

- Recommitment to the shared-enterprise

- Deep-distrust and counter-activism

In a sense, it’s a bit like Gartner’s beloved ‘hype-cycle‘ – the rise to the ‘Peak of inflated expectations’ as purveyed by the organisation’s promise, and then the crash down to ‘Trough of disillusionment’ as the promise is betrayed. Unlike the hype-cycle, though, there’s no rise back up to the ‘Slope of enlightenment’ or ‘Plateau of productivity’ – not with this organisation, at any rate, though quite often so with the shared-enterprise as a whole.

The key reason for this revolves around the trust-relationship – or lack thereof, perhaps. For inherent-anticlients, the trust-relationship was right down, right from the start, so in a sense the only way forward is up. But for betrayal-anticlients, the trust – or expectation of trust, from the promise – was gained and then lost: and unless clear and respectful action is taken, will keep on following that downward vector deeper and ever deeper, until the possibilities for recovering any kind of mutual-trust are eventually lost forever. That’s when things can turn seriously nasty, for everyone concerned, where even the most minor of disputes can suddenly spark off all-out war: again, Not A Good Idea…

We can see these processes in action in many commercial contexts, such as the disaster-area that arises from too many organisations’ muddled and much-mistaken notions of ‘customer-service’. But to get a better handle on all of that, it can be useful to pull right back to a global-level scale, and see how the same processes also apply out there. So following on from the other posts in this series on using enterprise-architecture and systems-thinking at that Really-Big-Picture (RBPEA) scope and scale – using as societal concepts of gender as a focus-theme to explore power, empathy, equality and inequalities, and violence and abuse – let’s look at anticlient-issues in the same way.

Following the classic feminist slogan of ‘the personal is political’, I’ll walk through my own path, extending over almost five decades, from becoming and then being a committed supporter of the feminist cause, to where I am now with it, as a deeply-despondent betrayal-anticlient of that cause.

Please notice, though, that rejecting that which calls itself ‘feminism’ does not make me ‘anti-woman’, misogynist – far from it, in fact. It’s just that to me, most of what describes itself as ‘feminism’ represents a total betrayal of the underlying principles that it claims to enact – and in exactly the same sense as how much of what calls itself ‘enterprise-architecture’ represents a total betrayal of the underlying principles that that claims to enact. By looking in more depth at the one, we should, I hope, also be able to gain a better insight and understanding of the other – which is the whole point of this RBPEA exercise, after all.

Anyway, here goes – and again, a reminder that this is personal, subjective, and does not in any way claim to represent ‘the truth for all’:

(What follows is a massive edit from the original version of this, which was about 5000 words in this section alone, much of it definitely TMI [‘Too Much Information’]. After the edit, though, it’s perhaps less evident that this isn’t just some kind of whinge that ‘they did it to me’: instead, yes, I’m well aware that I too am a long way from ‘perfect’, that I too have made plenty of mistakes about which I’m very far from proud, and that I almost certainly brought a fair bit of this down on myself through being over-trusting and the like. Yet all of the observation and analysis in what follows comes from a lot of deep-exploration and deep self-questioning over many years and decades: the detailed analysis and observation to back all of this up does exist, and is a lot more solid than most people would probably realise – but this isn’t the place for it here. In the unlikely event that you actually want more detail about any of this, all ya gotta do is ask…)

— Searching for the promise

I didn’t fit. Anywhere. Still don’t. That’s pretty much me, really.

I didn’t seem to fit with any of the then-current social definitions of ‘to be a man’. None of them made any sense to me. By the time I made it to art-school, at age eighteen, I was already pretty much lost. The only term that describes it well was Betty Friedan‘s ‘the problem that has no name’.

— Finding oneself in the promise

I’d come across this concept of ‘women’s liberation’, as it was known then. I saw it not just as being about liberating women from gender-stereotypes, but men too – for everyone. For me, it struck a real chord.

I came across Germaine Greer‘s definition of feminism, that it was “about exploring all the possibilities of being fully human, in a woman’s body and from a woman’s perspective”. I generalised that definition to “about each person exploring all the possibilities of being fully human, each in their own body, each from their own perspective”. That gave an enterprise-promise in which I could see myself – a place where I actually seemed to fit.

One memory from that time, though. Two young women, perhaps a couple of years older than me, talking excitedly on the train about some ‘women’s liberation’ rally they’d just been to in London. I asked them what it was about. Their instant response: “There’s no place in any of this for men!” That last word all but spat. Like acid. Straight in the face.

I guess I should have thought a bit more about that response…

— Commitment to the promise

At art-college and after, lots of reading and more: for example, Germaine Greer‘s The Female Eunuch; Betty Friedan‘s The Feminine Mystique; Starhawk‘s The Spiral Dance and Dreaming The Dark; and perhaps especially Ursula le Guin‘s anarchistic The Dispossessed. Also – and important for later – Erin Pizzey‘s Scream Quietly Or The Neighbours Will Hear, a ground-breaking work on domestic-violence (DV).

From that, certainly seemed that men had a lot to answer for. Even if men too needed to break free from their own gender-stereotyping, women’s needs seemed more urgent, and would need to come first. For men, it would be our turn too, eventually – that was the promise. It seemed fair enough, at the time…

— Self-doubt and self-blame

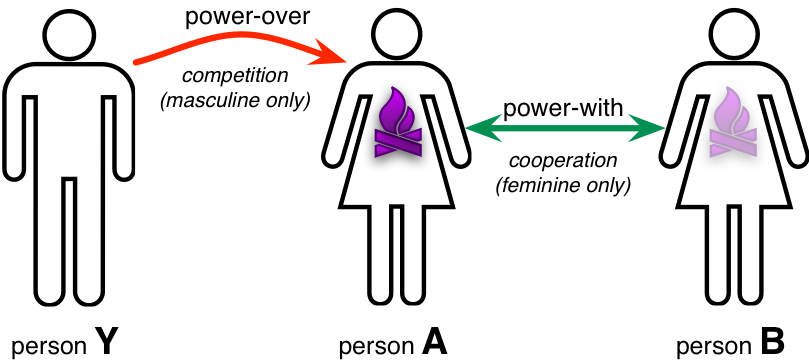

Quite quickly, though, the phrasing changed from “women’s needs come first”, to “men don’t have any needs”, to “men are to blame for everything wrong in the world” – as in Starhawk’s power-model:

I also saw the same in many of the ideas around ecofeminism, and in the takeover, by increasingly-extreme anti-male activists of the Greenham Common ‘Women’s Peace Camp’. I remember a Maoist-style ‘gender-reeducation’ session at Glastonbury, where we, as men, were taught to put ourselves down to prop women up, and to take on the responsibility and blame for everything. Seemed fair enough because, as we were so frequently reminded, “men are the problem, women are the solution”. Oh well…

Quite often, I found myself in the role of ‘male girlfriend’ – someone with whom (or at whom) women could talk, and take on the responsibility for solving their problems for them, so that they could then go back with renewed vigour to the respective ‘unreconstructed’ boyfriend. The role was essentially that of emotional-punchbag and one-way energy-source, somewhat like this:

What I didn’t do was question any of this. As a ‘pro-feminist man’ of that time, I accepted without question that everything was my fault, by definition, whichever way it went…

— Realisation and disillusionment

It wasn’t until some years after I’d moved to Australia, and by then in my mid-forties, that I at last started to ask serious questions about what I was doing. Once I stopped slavishly following ‘the party line’, and instead started to look and think, the whole story came apart. Some of the more extreme examples that I realised I could no longer ignore:

- In almost all feminist materials, systematic avoidance or denial of any responsibility on women’s part – yet without that responsibility, personal power for women cannot exist.

- During two centuries of feminist history, the major issue for each generation was the unintended-consequences of previous success – yet in each case all of this was blamed on men alone.

- Seeing the bleak reality of the ‘maid-culture’ in action – “one woman’s ‘liberation’ is built upon another woman’s entrapment”.

- The work on the revised-Duluth model on resolution of domestic-violence and abuse, and discovering that almost nothing of what we’d been told about DV was true at all.

- A personal realisation that the vast majority of violence and abuse that I’d had to face in own my life had been from women, not men.

- A personal realisation that the most common form of abuse I’d experienced was demands to suppress and silence what I actually felt – almost invariably suppressed by and/or on behalf of women.

- A personal realisation that my by-then lifelong learned-habit of putting myself down to prop others up, and taking on responsibility and blame where others wouldn’t, actually helped no-one at all.

- Being told by a publisher that she would only be allowed to publish my book on gender-issues if I was willing to pretend that I was a woman.

- Assessing feminist ‘deconstruction’ of ‘the patriarchy’, and noticing that the one ideology that they never applied such deconstruction to was their own.

- Noting that on government forms, the only minority-group not listed as a ‘minority group’ entitled to special-assistance was white heterosexual males.

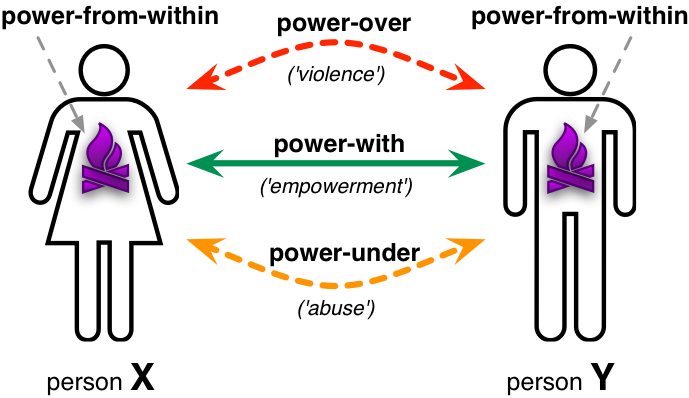

I also re-read Erin Pizzey’s Scream Quietly, and realised that she’d been emphatic throughout that DV was not gendered. It was a real sinking-of-the-heart ‘Oh sh*t…‘ moment, because it became clear that in terms of those societal problems around violence and abuse, what we were actually facing was this:

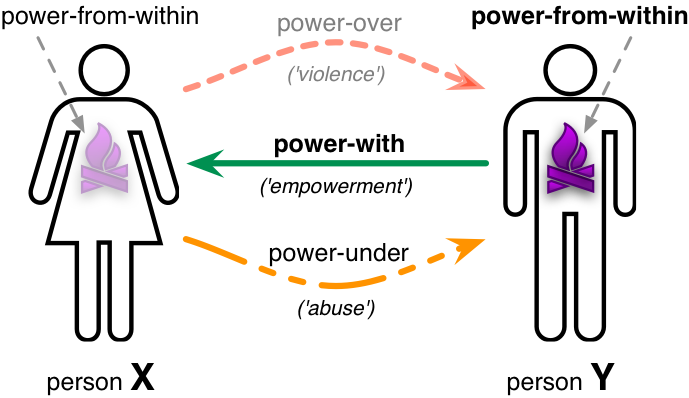

For which the only way out was to build whole-of-system awareness, around personal and mutual responsibility, and understanding those overall interactions as a system, a unified whole-as-whole:

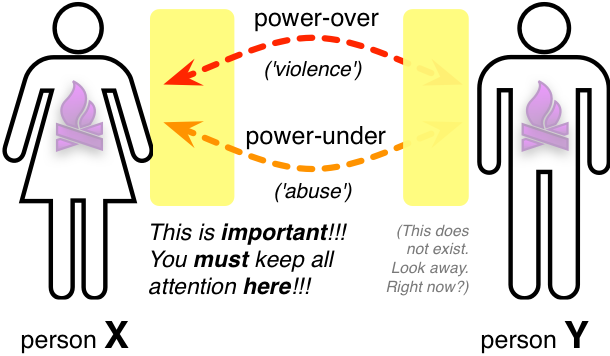

But what we’d been told, and ‘sold’, as ‘The Truth’, was this mess of male-blame and female self-aggrandisement:

And a morass of self-delusion, self-importance and outright lies ‘on behalf of women’, that looked like this:

In short, we’d been ‘suckered’ – big-time. The more I explored, the more I realised that the whole thing was somewhere between societal-scale delusion and societal-scale fraud, and all of it immensely destructive. And in supporting it, all I’d done was to ‘help’ make everyone’s life, including my own, that much worse than it already had been. Not a happy realisation…

— Anger and reaction

Almost none of what I’d been told for all those years was true: none of it. All of those oft-repeated promises that it would soon be men’s turn too: reality was that none of those promises were going to be kept – in fact with the structures and mindsets as they were, there was no way those promises could be kept.

And all of that pain and hell I’d put myself through, in the belief that doing so was actually helping women: reality was that probably all it had ever done was provide some brief entertainment for a few seriously-sick schadenfreude-addicts.

‘Cuckoo-feminism’ was a term I started to use at that time: ‘cuckoo’ as in ‘parasite that lays its eggs in other birds’ nests, that hatch out into monsters that destroy the birds’ own children’. It seemed an all-too-apt description…

For decades, I’d been a totally-committed supporter of the feminist enterprise – but had at last realised that I’d been totally betrayed. Not just me betrayed, but every man, and in many ways every woman too, on a truly global scale. Love for the movement turned to hate, for a while – and then turned to hate for myself, my own stupidity, for having allowed myself to be so deeply ‘suckered’. It was not a good time…

— Futility

After that, I went into a serious downer on this that lasted several years. At the end of that time I gave away all of my research-material, and my sizeable library on gender-issues: there seemed no point to any of it any more. It was all too big for just one person to tackle, and the dysfunctions and the vested-interests too deeply entrenched: any attempt to do anything about it would achieve nothing whatsoever other than further damage to me, and possibly to others as well. Pointless.

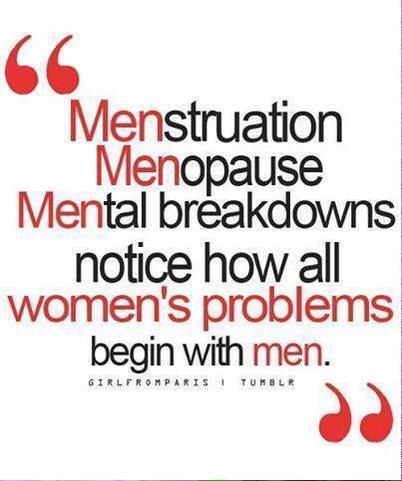

We’d thought of it as a ‘gender-revolution’, but I should have remembered that revolutions literally go round in circles. A perfect illustration of this the other day, in what someone in my EA community presumably thought was a ‘joke’:

- EternalMeQuotes: Sorry guys, I couldn’t resist 🙂 http://t.co/BP7e0U9nRi

This is the image attached to that Tweet:

A few decades back, we had to dissuade men from coming out with exactly this kind of abusive garbage. (In terms of those definitions we saw in the post on power and gender, it’s not only both abusive and violent, but intentionally so as well.) That this now comes from a woman rather than a man, and trashes men rather than women, makes no difference at all to that: there is no excuse for abuse or violence from anyone, to anyone. Unless we hold everyone to that principle – men and women alike – we’d be going nowhere but round in ever-decreasing circles. Which, sadly, seems indeed to be the case.

“Sorry guys, I couldn’t resist”: blunt fact is, yes, you could have resisted. And yet you chose not to do so, and chose to violate others instead – and then expect and demand that others must excuse you for that violence. Because you’re a woman, and therefore ‘incapable’ of being responsible for your own behaviour? Is that the only real legacy from five decades of feminism? Sigh…

— Recommitment to the shared-enterprise

To me it’s not about gender – it’s always about people as people, as themselves. So of course I’ll support individual women – I always have – and individual men, too: but as individuals in all of their individual complexity, their individual needs. I am deeply committed to that shared-enterprise: helping people find their own power-from-within, and their responsibilities in applying that power.

Yet gender is merely one tiny, tiny subset of that complexity: an almost-always-destructive distraction, if we try to make it ‘The Centre’ for every action. And that’s all that feminism has ever been, really: ‘right idea, wrong solution’. People-as-people is the ‘right idea’; gender-specific / gender-only feminism is merely one more ‘wrong solution’ – and a really poor ‘wrong solution’ at that, to the exact extent that it relies on Other-blame.

Oh well.

— Deep-distrust and counter-activism

I don’t hate the feminist-movement any more: it’s become even worse than that. The real opposite of love is not hate – it’s indifference.

That’s most of how I feel about this now: somewhere between indifference about the whole miserable mess, and outright disgust. ‘Women’s liberation’? – reality is that, just like men, the only thing that women have ever really needed ‘liberation’ from is their own stupidity and self-centredness…

For me at least, the betrayals run so deep, for so long, and so often, that when I now see something like #HeForShe, when I see yet more women complaining about ‘sexual harassment’, or ‘glass ceiling’, a woman abused, even a woman murdered, I just don’t trust it any more. Any of it. Unless I know the person in-person, myself, I no longer bother to put in the effort to believe it. In fact nowadays, even for the apparent worst cases, more often I find myself just wondering what kind of state-supported torture she put the guy through before he finally snapped.

Yeah, it really is that bad: the loss of trust really does run that deep.

To be honest, I too am very, very unhappy that I find myself feeling this way – in fact it’s become yet another way in which I beat myself up about what I feel – but the blunt fact is that it is what I feel about this at present. And please, don’t tell me that this isn’t what I feel, that I shouldn’t feel this, can’t feel this, mustn’t feel this, don’t feel this, as so many women (and men too) still insist at me: feelings are facts, and the blunt inescapable fact is that it is what I feel – and I literally do not have any choice about that. Yes, I do have choice about how how I respond to those feelings – which is why it’s called responsibility, ‘response-ability’ – and I’m usually as careful as possible about that: but unless and until I’m ‘allowed’ to accept and acknowledge that what I feel is what I feel, I can’t know what it is that I’m responding to. Those distinctions are utterly crucial, yet few people seem to understand them at all: instead, there are endless attempts to silence and suppress what others actually feel.

(I never did understand why so much of men’s emotional energy is focussed on the inanities of sport. I do now: reality is that it’s one the very few areas of men’s life where they are allowed to be truly passionate about anything at all, where passions of their own are not entirely proscribed. I still don’t understand the ‘what’ of sport, but at least I do now understand the ‘why’. Some of it, anyway.)

The blunt reality, again, is that Betty Friedan’s ‘the problem that has no name’ is a far more accurate description of men’s world than it ever was of women’s. The real feelings and lives of men are and always have been actively suppressed in our cultures, and – let’s be blunt about this – particularly suppressed by or on behalf of women. Which doesn’t work, because – just as for women too – our real feelings are who we are: and trying to force people to not be who they are is always going to be a project doomed to destructive failure right from the start.

Call this misogyny if you like – it won’t make any difference, other than perhaps make things even worse. It’s not about convenient blame-labels, it’s about loss of trust. And it’s all too clear to me now that until women do finally face up to their own misandry, their own violence and abuse, any attention paid to their complaints will likewise merely make things worse, for everyone.

Yet so far most of those women have made it all too plain that they’re not interested in my truth, or in any other man’s – so why should I be interested in theirs? After too many years and decades of incessant and relentless abuse, my willingness to engage at all on those ludicrously one-sided terms is long since gone.

There’s no reciprocity in feminism: in fact there never was any, right from the start. All that I see is that it’s always the same old one-sided demand: women-first somehow morphs every time into women-only, which doesn’t work because it’s women-only, and because its only method for dealing with anything is to try to blame it all on men. Even at best I see it as the same old pattern of false-promises of symmetry, of support – and promise betrayed, yet again, with yet more abuse to cover up the betrayal.

It doesn’t work, for anyone. Not in any real sense, at least.

So why should I bother to engage with it, to support it? Why should I bother? Seriously – why?

The anticlient’s tale: that’s how it feels right now.

Practical applications

(These ‘everyday enterprise-architecture’ parts of the posts of this series probably won’t have much to do with gender as such. Instead, what we’re after here is insights that we can apply right now in our routine, everyday enterprise-architecture practice – though as we’ll see below, difficult as those gender-themes often are, some of these concerns can also go a lot deeper than that…)

There are three key insights from the above that I’d suggest of real everyday importance to enterprise-architects.

The first is that feelings are facts in their own right. They’re not the same as physical-facts, of course: but that difference itself is crucial, because if we try to treat feelings in the same way as for physical-facts, we’ll merely make things worse – especially in an anticlient-type context.

The key here is that trust is a feeling. Anticlient-risks can occur in any context within which trust is an element of interactions across the enterprise. Which, actually, is pretty much everywhere – as you’ll discover quite quickly once you start to do any kind of trust-mapping for service-models and so on.

In a technology-oriented context, there might be a temptation to dismiss as irrelevant anything to do with feelings or anticlients or the like – after all, machines don’t seem to need trust, do they? But from a business perspective, that would be a dangerous mistake, because whilst trust might not be involved in the direct machine-based transactions themselves, it is still crucial to the set-up and follow-up phases – the more human ‘before’ and ‘after’ of the service-cycle:

To give a simple first-hand example that you’d know well, what are your own feelings when faced with one of those infamous ‘Terms and Conditions’ dialogs? If you don’t have any option to challenge or change any of those often very-one-sided conditions, how much can you actually trust that provider? Most of us end up not even bothering to read the yards-long screed of legalese, but just click the button and hope that it’ll work out somehow – because we don’t really have any choice to do anything else. And if that provider does then do something we don’t like – selling our personal data to someone else, for example – then we’re likely to feel pretty angry about it, whether or not it was ‘in the contract’ to which we’d had no real choice but to agree.

In short, when the relationship is set up as inherently unfair, a one-sided contract doesn’t help anyone: all that a contract will do is slow things down – and ultimately the only ones who ‘win’ from a one-sided contract are the lawyers… By contrast, when there’s high-trust, and maintained on all sides as high-trust, there’s no need for a contract anyway: and if anything does go wrong there, all parties sit down together to share out the respective ‘response-abilities’ and sort it all out. High-trust is low-friction, whereas low-trust is high-friction – and often very, very expensive, in many different ways.

The most spectacular example of those otherwise-hidden costs of low-trust is what happens when kurtosis-risk eventuates. This is particularly impressive, if also more than a bit unfair, when an entire industry has been playing ‘pass the grenade’, and the metaphoric ‘grenade’ finally explodes in just one company’s hands – as happened to United Airlines during the ‘United Breaks Guitars‘ incident, when they found themselves being thrown all of the anticlient-anger about other airlines’ betrayal of customers’ trust over deliberately-dysfunctional ‘customer-service’. Yet the overall costs of running a rigged, one-sided system are also a lot higher than they look at first glance, simply because so much effort has to be put into place to create, conceal and maintain the one-sidedness of the system. To put it at its simplest, from an architectural perspective, things run smoothest when they’re most balanced: any imbalance costs extra in effort to keep the whole thing moving.

The next key insight here is that, as mentioned in the ‘On abuse’ post, any form of ‘anything-centrism’ is bad news for an architecture-as-system. In part this follows from that point immediately above – that ‘things run smoothest when they’re most balanced’ – yet it’s also that when we focus only on one part of a system, we actually make it more unbalanced, by placing most or all of our effort in just that one place. If that one theme is allowed to become ‘The Centre’ – the only point where effort is allowed to be placed – then almost by definition the system will eventually find itself in an escalating feedback-loop into cascading failure and catastrophic collapse. In short, Not A Good Idea.

Although the example above relates to gender-issues at the RBPEA scale, the all-too-evident equivalent in mainstream enterprise-architecture is IT-centrism – not just the obsession with IT itself, but also the common assertion and assumption that, whatever ‘the problem’ might be, there’s always an IT-based ‘solution’ for that respective problem, and that, ‘by definition’, that IT-based ‘solution’ must be the best-possible option for that context, because it is IT-based. A mere moment’s careful thought should illustrate just how inane those assumptions really are – yet it’s scary to realise just pervasive they are throughout the industry, and yet how few supposed ‘enterprise’-architects ever bother to question them at all…

The only way to avoid this risk – the only way that works – is to keep our attention balanced as well: we take explicit care not to allow anything to become a sole, exclusive, ‘The Centre’. Instead, we maintain a distinct discipline of asserting that everywhere and nowhere is ‘The Centre’, all at the same time: the hard part, and the real skill of enterprise-architecture, is knowing where to place the appropriate attention at each moment, and what attention to place.

The other key insight is that we need to engage with inherent-anticlients and betrayal-anticlients in different ways, because for the former the trust starts low, whereas for the latter the trust had started high, but has been lost.

If we accept that some group of inherent-anticlients, relative to our organisation and its business-model, have something to show us that we need to know and act on – as in ‘anticlients are antibodies’ – then all it needs is straightforward engagement: start with active-listening, build respect, demonstrate reasons-to-trust, and build upward from there. The key stakeholders on each side would usually be well-known beforehand, or picked up quite easily via social-media and the like. The architectural challenges are all relatively straightforward, around ensuring availability of appropriate listening-mechanisms, suitable soft-skills, and mechanisms for shared feedback and learning. Once respect is in place, it’s not hard to make it into a ‘virtuous-spiral’ from which everyone ‘wins’: the crucial point is to ensure that everyone does ‘win’, and knows it.

Working with betrayal-anticlients is much harder, because the trust-vector is often steeply-downward by the time we’d get round to engaging with them, and we have to find some way to turn that vector around before we can even begin to apply the same tactics as we would use with inherent-anticlients. For an organisation, social-listening mechanisms such as social-media monitoring will be all but essential as a means to catch unacknowledged-complaints before they spiral into non-recoverability. (I especially like Nigel Green’s concept of ‘customer as citizen’ as a way to make sense of this.) Bear in mind, too, that when trust is fully lost, even offers to make things right may at first be interpreted solely as a prelude to yet another betrayal. None of this is easy: but if we don’t address these concerns – especially from those who are not merely the usual ‘chronic complainers’, but from key-influencers who previously had been active in promoting the organisation’s nominal value-proposition – then we would be setting ourselves up for catastrophic-collapse at some unpredictable point in the future. In these contexts, where betrayal-anticlients are ignored or worse, the exact trigger for catastrophic-collapse is unpredictable, but the probability of the collapse itself is all-too-predictable – and that distinction needs to be fully understood!

All of this becomes more difficult again as move out from the scope of a single organisation, and move up closer to the RBPEA scale, to where anticlient-relationship is not to an individual organisation but to a broader social-institution. The complication here is that social-institutions are somewhat amorphous, by their very nature: so if a shared-enterprise is built around an idea, then the respective anticlient-relationship is a feeling-based response to that idea – or, more usually, a felt response to and rejection of the social-institution’s real-world instantiation and implementation of that idea. The difficulty, for the anticlient, is precisely that the item rejected is so amorphous: there’s no one point of attack or response, no place to respond to. In some ways this makes it easier for the followers of that idea to convince themselves that there’s no problem – but what it does instead is cause the rejection of that idea to fester, until resistance can suddenly explode seemingly ‘out of nowhere’. There’s no way to defuse or mitigate the pent-up anger: so when it does explode, it can get very nasty indeed… – and often right out to a fully society-wide scope and scale, precisely because what’s being responded-to is a social-institution.

The personal example I gave above was in relation to the social-institution of feminism as a whole. What it describes is problematic enough: it should, I hope, be clear that there are real unacknowledged-risks there both for the social-institution of feminism, and, hidden behind the feminist term-hijack, for the deeper story around empowerment and self-expression in the far broader non-gendered sense. Yet even all of that – serious as it is – is almost trivial by comparison with the risks and dangers for some of the social-institutions that are deeper still.

All through this series I’ve put in repeated reminders that whilst gender is not the least of our problems at the RBPEA scale, it’s also by no means the worst. It’s a good example to work with for this, yet there are at least two other far-more-serious sources of mythquakes that could destroy the entire culture at a global scale: delusions around ‘rights’, and delusions around possession. Those are probably still ‘too far off the radar’ for most people to recognise as yet, though there are warning-signs enough for those who bother to look. Yet there are plenty of other examples that, for many people, are already a lot more visible and a lot closer to home – including the social-institution of politics within so-called ‘democracies’, and the social-institution of the money-system.

The money-system is a key element in the operation of a possession-based economy: it provides a means to resolve the ‘point-to-point’ problems inherent in barter-transactions, by providing a common abstract intermediary-means for exchange. Yet ultimately its operation is entirely dependent on trust: and that trust has been so much betrayed so often now – by bankers, politicians and others, particularly in relation to state-based fiat-currencies – that trust in the system itself is now all but lost. We can see one type of response to this in the development of alternate-money schemes such as Bitcoin, and in literally tens of thousands of plans and models and even some real-world implementations of ‘alternative-currencies’ – almost all of which, in practice, have served only to highlight the deeper problems within the concept of ‘money’ itself…

When a single bank or a single currency goes into collapse, the outcomes are often extremely unpleasant for (almost…) everyone involved: that point is very well understood, in theory at least, if not necessarily in practice. Yet scale all of that up all the way, to where trust in money itself is lost – not just a single currency, but every currency, the entire concept of money-as-trusted-exchange. Kinda scary, yes? And yet if you look around, and ask a bit deeper than usual, as an architect should, you’ll see that that’s the point, at a fully global scale, that we’re very close to right now. So if that’s the case, what alternative architectures do we have available to put in its place – in a very real hurry, and at a global scale? It might seem kinda abstract right now, but that’s the kind of real RBPEA-type architectural-challenge that we’re up against: and I honestly don’t think that we have much time left before it’s going to be needed for real.

The political-system – well, that’s possibly in an even worse mess. It’s quite probable that right now, in Western-style democracies, trust in the political-system is at an all-time low: not just loss of trust in individual politicians, or political-parties, but trust in the system itself. Much as I described about the social-institution of feminism, above and earlier in this series of posts, the social-institution of ‘democratic’ politics has become so hijacked by lobbyists and vested-interests and ‘more-equal-than-others’ privilege-games that it just doesn’t work any more: not for most people, anyway. In many if not most countries – including, now, the US, UK and Australia alike – it’s pretty much collapsed back into the natural default-state for a possession-economy: some kind of blend between full-blown kleptocracy (‘rulership by thieves’) and full-blown paediarchy (‘rulership by, for and on behalf of the childish’), with only the thinnest and decreasingly-credible veneer of ‘panem et circenses‘ to cover up the theft – but now all the way out to a fully global scale. Now link all of that to some non-negotiable constraints – in particular, global-scale climate-change, the inherent impossibility of infinite-growth on a finite planet, and the increasing systemic fragility of global economics and trade – and it should be obvious that we’re up against a huge, huge RBPEA-type problem that very few people are even beginning to face as yet. (To be honest, I haven’t seen much that’s genuinely new on this since Stafford Beer’s work on ciberfolk, way back in the early 1970s.)

The point here is that fractal approaches to enterprise-architectures can and should be able to go both ways. As here, in these series of posts, we can go up to the RBPEA scope to find new insights to apply back at the everyday enterprise-architecture level; but if we’ve done our EA work right, we should also be able to take and apply our EA experience all the way up to a maybe fully-global scale – it’s all one continuum, all the same spectrum. That, I hope, would be the single most important insight to take away from this series.

Leave a Reply