RBPEA: Wrapping up on gender

In what ways can we use explorations at the RBPEA (Really-Big-Picture Enterprise-Architecture) scope and scale to create insights for practical use in everyday-level enterprise-architectures? For example – in the specific case of this blog-series – what can we learn from an RBPEA-type analysis of societal concepts about gender, that we could use in work-areas that, in themselves, probably have no immediate connection to gender-issues as such?

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this series – some 35,000 words so far, and more than forty graphics – packed into seven, uh, somewhat over-long posts:

- Return to RBPEA – introduction to the series

- RBPEA: On power and gender

- RBPEA: On empathy and gender

- RBPEA: On equality and gender

- RBPEA: a quick note on inequalities

- RBPEA: On abuse and gender

- RBPEA: An anticlient’s tale

It’s time now to summarise and wrap-up the series, and look once more at practical uses for what we’ve learnt from this exploration.

(As an aside, this has been perhaps the hardest blog-series I’ve ever had to write, and so far probably the least-read – not exactly a great return-on-effort, it might seem! Yet I’m also aware of just how long it’s taken for other key ideas I’ve worked on over the decades to come into mainstream awareness and practical use. For example, the notion that the term and practice of ‘enterprise-architecture’ must literally mean ‘the architecture of the enterprise’, rather than merely ‘the architecture of enterprise-wide IT’: to me, that was ‘obvious’ right from the start, nigh on a couple of decades ago, whereas its necessity and inevitability is still only just seeping into mainstream EA now. The same with this series of posts: if the ideas here don’t seem to make sense right now, or clash too much with your current assumptions, come back here again in a few years’ time: I’d all but guarantee that it’ll make a lot more sense by then…)

Let’s quickly summarise what we’ve found from each of the posts in the series:

— In Return to RBPEA we went back over the core RBPEA process, itself drawing on well-established principles and practices for systems-thinking:

- explore a context that is of interest

- identify the conceptual mismatches that occur within that context, and that make it difficult to achieve effective results within that context

- identify the vested-interests that drive and maintain the current dysfunctionalities in the context, and, where possible, devise strategies and tactics to disarm and disengage those vested-interests

- assess the details of the dysfunctionalities in the context, and identify or design workarounds for those problems, and methods to work on the context when the dysfunctionalities are disengaged

- document the end-results in various forms, as appropriate (as the blog-posts themselves, in this case)

And, for this series, we would then take the key insights derived from that process, and show – in a ‘Practical applications’ section to each post – how to apply those insights back at the more everyday-level of enterprise-architecture.

Using the concept of mythquakes as major themes at the ‘really-big-picture’ level, I suggested that gender-issues would be an appropriate theme to work with for this purpose: far enough ‘above’ mainstream-EA to trigger off useful insights, yet still close enough to everyday experience such that insights could arise without seeming too ‘alien’. We also reiterated the personal challenges around this type of work:

- What are you certain is true, is indisputable fact? How do you know it’s true? Who told you so?

- With perhaps a little less intensity, what do you assume is true, even if you don’t know for a fact that it’s fact? In what ways do you trust that it will remain ‘true’? And why?

- What would happen to you, and perhaps to others, if you find out that it’s not true, or is true only under particular circumstances? What would change? And what, if anything, would remain the same?

From there, we moved off into the first of the specific focus-themes, around concepts of power.

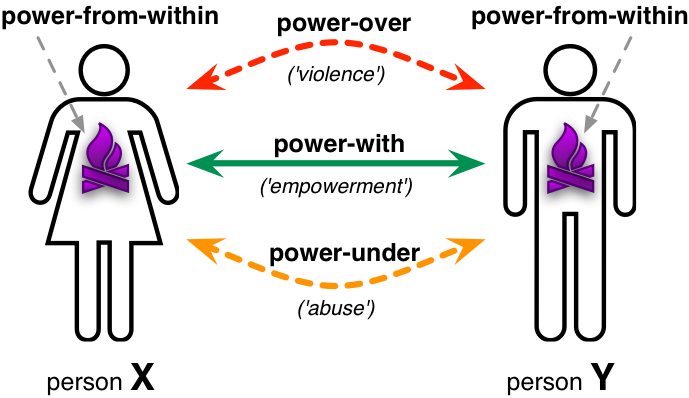

— In RBPEA: On power and gender I outlined some of the common models on power in a social context, and showed how the various attempts to make them gendered had ended up being more of a hindrance than a help. To sort out the mess, I derived a non-gendered power-model that could be summarised as follows:

- Power is the ability to do work, as an expression of personal choice, personal responsibility and personal purpose

(note: power is the ability to do work – not the ability to avoid work) - Work is whatever people choose to do (physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, etc)

- Power-from-within is the ability to source and access human power from within the Self

- Power-with is the ability to assist each other to generate and access power-from-within, and to share that power with others

(alternatively, power-with is the ability to do work, as an expression of shared choice, shared responsibility and shared purpose) - Power-over is any attempt, by anyone, toward anyone, to prop Self up by putting any Other down

- Power-under is any attempt, by anyone, toward anyone, to offload responsibility onto the Other without their engagement and consent

Or, in visual form:

We also briefly explored the common notion of ‘rights’; why and how it tends to create serious dysfunctionalities in the social context and elsewhere – particularly where purported ‘rights’ are inherently asymmetric; and why and how to replace ‘rights’ with sets of interlocking mutual-responsibilities.

— In RBPEA: On empathy and gender we explored the practical implications of two common errors around sympathy and empathy:

- mistaking sympathy for empathy

- mistaking a kind of self-centric ‘pseudo-empathy’ for real-empathy

In sympathy, the Self attempts to merge with the experiences and feelings of the Other – which can be very powerful, but also extremely dangerous for all involved. In general, it should not be attempted without appropriate safeguards and without explicit permission from the Other.

In pseudo-empathy, the Self imagines alignment with the Other – “what I think I would feel if I were in what I believe to be the context of the Other”. In most cases, it’s worse than useless, as its main result is merely a reaffirmation of existing prejudices and serious misinterpretation of the actual context. In my experience of feminist literature and theory, their concept of ’empathy’ almost invariably turns out to be some form of this literally self-centric delusion; the resultant inability to actually empathise perhaps also explains why most feminist theory demonstrates such poor understanding – or even awareness – of men’s real experience.

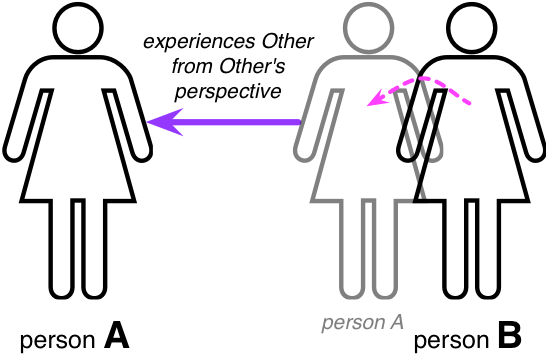

In true empathy, the Self seeks to understand and experience the world from the Other’s perspective, whilst still being the Self – and fully aware of the difference. Unlike with pseudo-empathy, we explicitly guard against imposing our own assumptions on our felt-experience of the Other’s world; and unlike with sympathy, we take care to not merge with the Other – otherwise, again, we’d risk inappropriately distorting our view of that world, and possibly the Other’s view of their world as well.

The whole point of true-empathy is to map the contrasts between the different ‘worlds’, starting from the respectful assumption that the Other’s experience of their own world is at the very least as valid as ours. Once this has been done, contextually-appropriate choices can perhaps be identified: but not before.

An example of the crucial difference here can be found in feminists’ arguments about the Islamic hijab and niqab. Using pseudo-empathy, Western feminists often interpret these garments as ‘proof of patriarchal oppression of women’; a true-empathy approach, by contrast, might well discover that usage is what the respective women choose for themselves – especially in the harsh desert context in which usage originally arose.

— In RBPEA: On equality and gender, we started with an assertion about gender-equality:

- The needs, concerns, feelings and fears of women and of men are of exactly equal value and importance.

We also took an early definition of Germaine Greer’s about feminism, and generalised it to a non-gendered form:

- “It’s about exploring all the possibilities and responsibilities of being fully human, each in their own body, from their own perspective.”

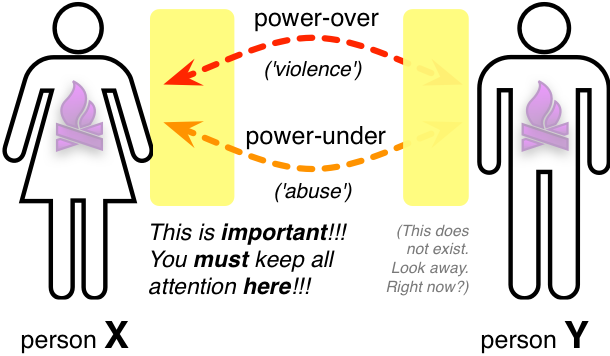

The aim of this post was to explore the extent to which such notions of equality have become distorted in real-world practice into an Animal Farm-style “some are more equal than others” for one gender or the other. Although it’s often purported that gender-equality everywhere is still skewed towards men – ‘the patriarchy’, to use the popular feminist term – almost all of the real-world examples we looked at indicated that in Western cultures it’s usually far more skewed towards women, but in a highly-dysfunctional way that we could summarise visually as:

Far from moving towards a true gender-equality, it seems we’re now moving further and further away from it, at an accelerating pace, but in ways that are actively concealed through tactics such as relentless male-denigration and male-blame at a whole-of-society scale. This creates steeply-increasing kurtosis-risks for society as a whole that are, bluntly, Not A Good Idea…

— In RBPEA: a quick note on inequalities we noted that ‘identical’ is not the same as ‘equal’, and that some non-identicalities are actually highly-desirable: making something less identical can actually make it more equal, in terms of outcomes. Non-identicalities in skills, talents and experiences also provide a key driving force for power-with – the means by which people assist each other in finding their own power-from-within.

However, it’s crucial that power-with relationships are mutual and ‘fair’ – otherwise, by definition, they become inherently unequal. In particular, structural-unfairness – unfairness built-in to the relationship by one-sided rules and suchlike – is always ‘bad-news’, because it will always cause the relationship to fail over the longer-term. Unfortunately, the latter is becoming more and more common in Western cultures, almost always biased against men – such as in the #HeForShe initiative, in which support for women is demanded from men, with only further abuse and/or violence offered in return. Inherently-dysfunctional structures of that type may seem to work for the ‘winner’ in the short-term, but are clearly not viable over the longer-term.

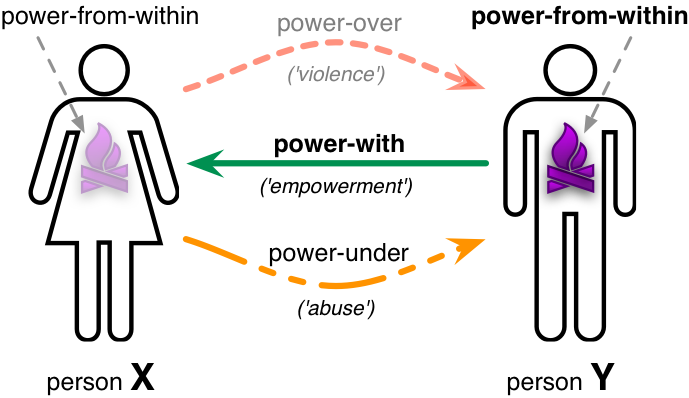

— In RBPEA: On abuse and gender we used the previous definitions on power-over (‘violence’) and power-under (‘abuse’), and the assertion on equality of ‘needs, concerns, feelings and fears’, to explore the common public-perception of gender-violence as something that only men do, and only to women – and that it should be responded to as such.

The one-line summary, though, is that that public-perception turns out to be almost totally false – it has almost no basis whatsoever in real-world evidence or real-world fact. Instead, what we find, from what little real data exists on gender-abuse, is that it is, in essence, a sad yet largely-symmetrical ‘balance of terror’:

The societal perception that gender-abuse is primarily ‘men do it to women’ actually arises from a combination of wishful-thinking, self-delusion, arbitrary ideology, scientific incompetence and outright fraud, all of it on a truly startling scale – a misframing that could be summarised visually as:

No-one doubts that, societally, there is indeed a real problem around male violence towards women – and we need to face up to it. Unfortunately, that’s literally less than half of the real problem – a lot less than half of it, in fact. Until we face up to the whole problem, and tackle it as a whole, anything we do on just one part of that overall problem – as at present – will and can only make things worse. (That fact may well be unpalatable for many, but it is a fact – and no amount of Other-blame will change it.)

The core principle on which all violence-resolution work needs to be based is that:

- There is never an excuse for abuse or violence, from anyone, to anyone, including Self.

Which is not as simple as it might seem, because there are always attempts to excuse or pre-excuse some form of abusive action or inaction by one party or another; and most of the mechanisms that we use to attempt to ‘resolve’ abuse or violence – such as blame or punishment – are themselves abusive or violent. It gets kinda tricky…

Although there are some gendered-overtones, in practice the only way that works is to remove all assumptions about gender from the overall discussion. Labels don’t help: instead, people are people, people make mistakes, people need somehow to learn how to help everyone recover from those mistakes, and how not to repeat them in the future – all of which is essentially the same as for all other enterprise-architecture concerns, in fact.

— In RBPEA: An anticlient’s tale explored a key problem in larger-scope enterprise-architecture: how someone becomes an anticlient – a person who’s committed to the same nominal aims of the same shared-enterprise, but vehemently disagrees with how you or your organisation are acting within it – and what, if anything, could be done to rebuild their trust. To illustrate this, I used my own first-hand experience, over almost five decades, of transitioning from an active proponent and supporter of nominally-‘feminist’ ideals, to (now) a deeply-despondent ‘betrayal-anticlient’ of that movement. The journey I described went through nine distinct phases:

- Searching for the promise

- Finding oneself in the promise

- Commitment to the promise

- Self-doubt and self-blame

- Realisation and disillusionment

- Anger and reaction

- Futility

- Recommitment to the shared-enterprise

- Deep-distrust and counter-activism

In part, the driver towards the anticlient-positioning was the one-sidedness of it all, the lack of reciprocity in the expected/demanded support-relationships – a structural unfairness, exactly as summarised above for the post ‘RBPEA: a quick note on inequalities‘. Perhaps even more, it was a sense of disgust at the outright dishonesty that had underpinned that whole story: the slow discovery that, ultimately, almost none of the claims of feminism turned out to be true, but instead were just irresponsibility and subject-based abuse on a truly massive scale, coupled with a very ‘dirty’ game of “some are more equal than others”. (I’ll admit that it’s difficult to keep the disgust and disappointment out of my metaphoric voice as I write this now…)

(For another non-gendered example of the same anticlient-reactions, take a look at the anger behind the riots happening right now in Ferguson, Missouri and elsewhere in the US, following the acquittal of a white police-officer who’d shot and killed a black teenager. Remember that this is about feelings – not necessarily about purported ‘facts’. In that sense, in some ways it’s not about that individual case, but too many other cases like it, in too many other places across the US, over too many years, leading to a general disgust at and rejection of the mainstream’s implementation of the shared-enterprise of ‘justice’: “right idea, wrong implementation”.)

The core to all anticlient-issues is that feelings are facts – it’s a literally visceral rejection or antipathy. The hardest part of working with anticlients is to rebuild trust, because the trust is usually already on a steeply-downward vector by the time that any acknowledgement of the problem takes place. Anticlient-relationships are particularly problematic when the problem is not so much with an individual or organisation but a more amorphous social-institution (such as feminism, in the worked-example here), because there is no clear point of reference or for resolution. However, anticlient-risks cannot be ignored, because, if left to fester all the way to breaking-point, they always have the potential to destroy the enterprise as a whole.

Practical application

Most mainstream enterprise-architecture would not – and probably should not – have much, if anything, to do with gender as such: but all of this work at the RBPEA level brings back insights that do have direct applications in everyday enterprise-architecture.

From the post ‘RBPEA: On power and gender‘, that set of definitions on power are directly applicable not just in the soft-skills aspects of architecture work, but even in mapping out relationships between IT-systems. For example, in a control-system, an element that runs ‘open-loop‘ is in effect offloading responsibility for the overall system onto other elements of that system – a direct instance of metaphoric ‘abuse’ of those elements.

From the post ‘RBPEA: On empathy and gender‘, the distinctions between sympathy, pseudo-empathy and empathy are crucially important in key architecture concerns such as use-case modelling, customer-journey mapping, ‘outside-in’ modelling and much more.

From the post ‘RBPEA: On equality and gender‘, the gender-oriented equality-assertion that “The needs, concerns, feelings and fears of women and of men are of exactly equal value and importance” could usefully be generalised to:

- The needs, concerns, feelings and fears of all stakeholders are of exactly equal value and importance.

This has direct applications in mapping of stakeholder-relationships and stakeholder-trust, for example, and in investor and beneficiary interaction-mapping in Enterprise Canvas. It’s also a key anchor-reference when mapping out relationships with stakeholder-groups: if the attention paid to different stakeholder-groups is not equal, there need to be good and defensible architectural-reasons why this should be so.

From the post ‘RBPEA: a quick note on inequalities‘, both of its key points have direct applications: looking for useful non-identicalities to leverage, and the very real risks of allowing structural-unfairness to become part of any system – not just human-systems, but IT-based systems as well.

From the post ‘RBPEA: On abuse and gender‘, that core-principle of “There is never an excuse for violence or abuse, from anyone to anyone” is again extremely useful – especially when we generalise it to include relations between IT-systems that, metaphorically-speaking, prop themselves by putting other systems down, or offload responsibility onto other systems without their engagement and consent. (It can sometimes take a bit of imagination to fully understand and apply that metaphor, but once we do, it really is extraordinarily powerful in terms of the insights that it can elicit.)

The other aspect of it is a warning of just how easy it is for a culture of blame and counter-blame to develop within an organisation or team, or across any transaction, as a way to attempt to offload responsibility onto others: but since blame is itself a form of violence or abuse, there’s no excuse for that either! So whenever we see some kind of blaming take place, it’s useful to use that as a trigger to change the incident into group-learning, where the group as a whole take on the shared-responsibility for resolving the situation, rather than attempting to dump it all on one, then another, then another.

Finally, in the post ‘RBPEA: An anticlient’s tale‘, there’s that fundamental warning that anticlients represent very real risks to an organisation and its enterprise, and that they can not be ‘safely ignored’. Learning how to include trust-mapping and trust-response within an enterprise-architecture and its real-world implementation are crucially-important for the health of the organisation and its enterprise.

Leave a Reply