Two words

There we were, my colleague and I, discussing the possible merits and value for me of going to yet another conference. This time business-architecture rather than ‘enterprise’-architecture, and reasonably-priced too – unlike so many conferences these days. Looked good.

Yet as the ideas bounced back and forth between us, a sad realisation slowly arose: that there was no point in my going. It’s gone past that point now. I should have heeded my own warning and advice back at the end of last year, and properly moved on from the ongoing shambles that is ‘enterprise’-architecture and its equally-disastrous derivatives. That would have saved me several months of further misery…

There seem to be just two words that summarise where I’m at right now: anhedonia, and rōnin.

The first of these – anhedonia – came up in a tweet a few days ago via Sinan Alhir. The tweet consisted of just that one word, and a link to this image:

It’s not quite correct as a translation: anhedonia literally means ‘without pleasure’, and that’s a more accurate description of how I feel at present about the whole EA-farrago of the past few years – nigh on a whole decade now, in fact. It’s not at all that I don’t care – in fact probably the real problem is that I care too much. But pleasure? Not much. Not now. Not for a long time.

A full decade ago, back at Australia Post, we’d established early on in our enterprise-architecture work that IT-centrism was a dangerous mistake, and that EA would succeed only when it was a literal ‘the architecture of the enterprise’, with everything in that enterprise as an inherent aspect of that scope.

At the end of that gig, I moved back to Britain, in the expectation that the EA-disciplines there would be more advanced than we had on-hand back in Australia.

I was wrong.

Very wrong.

It turned out that seemingly anywhere outside of the ‘small countries‘, so-called ‘enterprise’-architecture was so backward that it still promoted IT-centrism as ‘a good idea’. I was mocked and more, very hard, and very often, for suggesting that EA could even be anything but IT-centric. Since then, working with, or in parallel with, various other folks such as Len Fehskens, Kevin Smith and Stuart Boardman – to name a handful of that all-too-few – it’s now taken the whole of that decade, with a lot of pain and a lot of patience (or as much of it as I could muster, which I’ll admit sometimes wasn’t much…) to get the ship-of-fools that is mainstream ‘EA’ to turn enough away from its previous path to avoid running itself right onto the rocks. To date, anyway – though the struggle still goes on…

It’s become a duty. An unending chore. Month after month, trying and trying to get people to just see the simple, basic, fundamental, in-your-face errors that typify so much of current so-called ‘enterprise’-architecture. Just to give one simple example, by now it should be more than self-evident, to every competent enterprise-architect, that the bewretched BDAT-stack cannot be used as the basis for a viable architecture for anything more than the most basic of IT-infrastructures. And yet it’s still used as the base for most existing ‘enterprise’-architectures and ‘EA’-training. Why is it seemingly so ‘impossible’ to get people past that one asinine mistake? Why oh why oh why???

And just when it looks like we may, just possibly, just-perhaps be beginning to at last get the message to start to sink in, along come a new of bunch of – yes, I’ll be blunt and say ‘idiots’ – who think that a shift from IT-centrism to ‘business’-centrism (or, more usually, just money-centrism) is somehow an improvement? Oh gawd…

What it feels like right now is best summarised by the words of singer/songwriter Roy Harper, in his satirical song ‘Hors D’Oeuvres‘:

You can lead a horse to water

but you’re never going to make him drink;

you can lead a man to slaughter

but you’re never going to make him think

Sigh indeed…

Which, I will admit, does drive me rather too often towards a feeling best described in visual form:

But the work is not pointless, of course: there’s a very real point to it, and an urgent one too – though few people seem to see or understand that as yet. And working to resolve that list of human needs – “someone to love, somewhere to live, somewhere to work, something to hope for” – will always continue onward, at every scale, regardless of what society we live in.

So yes, there’s a point to it, and the work needs to be done – by someone, at least. And for quite a long while now, one of the seemingly-so-few of those ‘someones’ has been me.

Yet there’s a catch – a huge catch. Or several of them, rather.

One is that – particularly with the work on RBPEA (Really-Big-Picture Enterprise-Architecture) – the scope and scale I’m working on, or for, is so vast and so problematic that it’s still not really practical, or feasible, or whatever, to attempt to do much in the form of design or implementation. What I’m working on most at present is tools and guiding-principles, trimming, clarifying, simplifying, creating metaphors and examples that, if at all possible, are simple enough for at least some people to begin to understand. The catch there is that once people at last do get it, their usual immediate response is “Well, it’s obvious, isn’t it?”

They don’t see any of the vast amount of pain and effort that went into making it seem ‘obvious’.

Which means that, to them, I seem to have done almost no work at all. None worth paying for, anyway…

Which means that I don’t get paid.

Ouch…

To make it worse, another problem that I face in this is that most of this work is about futures – about getting ready for literally fundamental changes, all the the way up to a literally global scope and scale, that are now-undoubtedly heading our way Real Soon Now, whether we’re ready for them or not. It’s futures-work that must be done, by someone – otherwise there’s literally no future for anyone. (Or no future than anyone would want, rather.) The catch there, though, is that because it’s about the future rather than the Now, no-one seems willing to pay for it…

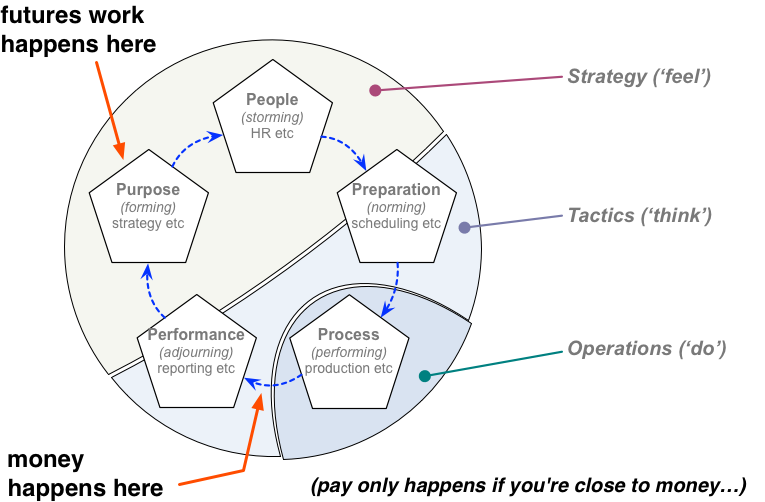

I described this dilemma in some depth some while ago in the post ‘What futurists do, and why‘. Or, to summarise it here in visual form:

So why not just stop doing it? – that’s what people ask me. Why not go back to doing mainstream ‘enterprise’-architecture like everyone else, and do this big-picture stuff as a part-time thing, an unpaid hobby or suchlike? Well, yeah, sort-of: except that the very real urgency behind all of this ‘big-picture stuff’ – which scarily few people seem to have understood as yet – means that it really does need to be done as a full-time activity, by a lot more people than are doing it at present. Someone has to do it: seriously, we’d be suicidally crazy if we don’t. Sometimes I wish it wasn’t me: but right now, it is. Oh well…

And ‘go back to doing mainstream enterprise-architecture’? – there are a couple of serious catches there too. Of which the most self-evident is that the only – I repeat, only – so-called ‘enterprise’-architecture roles or contracts that I see in this benighted country are for various aspects of IT in banks or other financial-institutions. And since my IT is around a decade out of date now, it kinda makes little sense to even bother to apply for such roles – let alone spend the hour upon hour explaining to recruiters and others what it is that real enterprise-architects (rather than, say, project-managers or solution-architects) actually do. Then there’s that definitely non-trivial ethics-problem: all of the research I’ve done on RBPEA indicates that the money-system is itself one of the fundamental drivers towards societal failure and full societal collapse – and the real need is to dismantle the damn thing, not prop it up still further beyond its long-expired use-by date.

Just to add to the (non)-fun, many people still seem to expect – if not demand – that because I’ve been advocating a future based on post-money / post-possessionist economics, I therefore ‘should’ and ‘must’ do everything ‘for free’. In that future world, yes, I would very much hope to do so – though we should note that type of context, ‘for free’ would have a very different meaning to that it holds at present. Yet right now, to make this work, I somehow still have to be able to ‘make a living’ within this insane culture’s insane ‘economics’ – and there doesn’t seem, as yet, to be any way for me to do so.

The reality is that all of the above leaves me more than a bit stuck: I just don’t know which way to turn any more. I’ll admit I’m probably one of the world’s worst self-marketers, which I know doesn’t help – perhaps especially since big egos and bullying seem to be all but de rigueur in so much of this field. And yes, I do know it’s been an ongoing problem for me for some years now, as I commented back in the post, ‘“I’m sorry, but I just can’t afford it”‘ – but it’s getting worse almost by the day now, as my few reserves dwindle away into near-nothingness with no apparent relief anywhere in sight. Sigh…

Which brings me to the second of the two words here – rōnin. According to the Wikipedia entry:

The word rōnin literally means ‘wave man’. That, however, is an idiomatic expression that means ‘vagrant’ or ‘wandering man’, someone who is without a home. The term [also] came to be used for a samurai who had no master. (Hence, the term ‘wave man’ illustrating one who is socially adrift.)

(The Wikipedia entry also comments that “In modern Japanese usage, the term also describes a salaryman who is ‘between employers'”.)

Well, I probably wouldn’t describe myself as much of a ‘warrior’, in any sense of the term. But ‘wandering man’, “one who is without a home”? – yeah, that would seem to fit me well enough, in a fair few senses too. ‘Masterless’, certainly, ‘one without a master’ – I’ve always been too much of an anarchist to accept from anyone any arbitrary orders that don’t make real-world sense. And likewise “a salaryman who is ‘between employers'” might fit, I suppose – at least in the sense that although I’ve never yet been a ‘salaryman’, I’ve always been ‘between’, in one sense or another.

Yet of all of the descriptions above, “one who is socially adrift” is probably the most accurate meaning for me there. Almost from the very beginning, I’ve always felt or found myself in the role of the Outsider, one who does not fit whatever it is that’s there to fit to. I’ve never felt that I really belonged anywhere, or with anyone – or, perhaps the inverse, that it’s seemed there’s never been any place or person that’s particularly wanted me to belong there. (Whether that’s factually ‘true’ or not barely matters here: the core is that feelings are facts in their own way, as discussed here on this blog at various times.) For example, to me it certainly feels that, right now, perhaps none of that ‘list of human needs’ really applies within my own life – “someone to love, somewhere to live, somewhere to work, something to hope for” – and for some of that list probably haven’t done so for a lot longer than I’d like to remember. So yeah, “one who is socially adrift” is all too accurate: a rōnin in that sense at least. And yes, that too feeds that sense of anhedonia – perhaps especially now.

One part of the description of the rōnin that doesn’t make sense to me, though, is that it’s a status that’s supposed to be something shameful:

One who chose not to honor the code was ‘on his own’ and was meant to suffer great shame. The undesirability of rōnin status was mainly a discrimination imposed by other samurai and by the feudal lords.

To me, I’ll admit, I see it as more the other way round: that it’s the status of ‘possessed’ by some self-styled ‘feudal lord’ or ‘master’ that should be the real source of shame. Why on earth would anyone give up all of the choices in – or even of – their own life, to some parasite who steals the surplus-value from everyone else’s labour, as a purported ‘feudal right’? The whole notion of a ‘master’ was a sick con-trick in feudal times, held together by little more than shaming and social-discrimination; the similarly sick joke of ’employment’ is probably no better in these times, in fact in many ways arguably worse – much of it held together by the equally sick myths and manipulations of the money-economy. Shame indeed, and entrapment too, for almost everyone: but it seems that, for now, we’re stuck with it, whether we wish it or not.

Whether supposedly ‘shameful’ or not, that role of the Outsider is essential, because without it, no social change is possible – or response to change, when change is forced upon us, as it certainly will be somewhen Real Soon Now. And as part of that role – as I’d described in the post ‘What I do and how I do it‘ – I’ve long since had a clear, distinct step-by-step process that I’d used each time I came into a new discipline or domain:

- explore a context that is of interest

- identify the conceptual mismatches that occur within that context, and that make it difficult to achieve effective results within that context

- identify the vested-interests that drive and maintain the current dysfunctionalities in the context, and, where possible, devise strategies and tactics to disarm and disengage those vested-interests

- assess the details of the dysfunctionalities in the context, and identify or design workarounds for those problems, and methods to work on the context when the dysfunctionalities are disengaged

- document the end-results in various forms, as appropriate

That blog-post described four discrete domains in which I’d applied that process: I’ve probably done it for many more, if on a smaller scale. Yet what’s missing from that process – an absence that’s caused me much pain and more, as I’m just beginning to realise now – was this final step:

- identify when to finish, and move on

The mistake I’ve made here over the past few years is that I’ve allowed myself to be dragged back, and dragged back, and dragged back, to the trials and travails of mainstream ‘enterprise’-architecture – literally years now since I should have moved on to fields anew.

Hence the omnipresent anhedonia of the present time – the signal that it’s time for the rōnin to come back to the fore within my own story. Something new beckons: I don’t know what it is as yet, though no doubt it won’t be far off now.

And no reason why the wandering rōnin should not come this way again, of course: no doubt that that’ll happen from time to time, especially if people ask for it. But if so, please do respect the fact that all work has its costs in some sense or another – and I’ll no longer carry those costs for you.

In enterprise-architectures as elsewhere, it’s time for more realism about how the world really works – because unless you do provide real support for the futures-work that’s done by people like me, you will have no viable future. You Have Been Warned, perhaps?

Tom: I am sure that you are aware that it goes very much against the grain for middle-level managers to make the kind of selfless tradeoffs that realizing a RBPEA requires. Beside sublimating self-interest, it also requires a commitment to persistently work at it, for which most ‘salarymen’ in today’s corporations don’t feel they have the time or latitude. Impermanence of business and operational models and the need to get what can be gotten now all conspire against RBPEA. However fulfilling it might be to be able to help an enterprise realize a near-optimal architecture, we have to recognize that such a state probably has the life of a free Higgs bosun and immediately upon coming into existence it will begin to revert to the chaos from whence it came. Perhaps we will need to be content to nearly-optimize smaller units within larger entities, assuming the external factors beyond the control of the unit management as givens.

A little on the skeptical side, I know, but I have worked in too many places and built too many things designed to improve the way that things were managed that died immediately after completion because doing things right is too hard. As you observed, we need to “identify when to finish, and move on.”

Howard: “I am sure that you are aware that it goes very much against the grain for middle-level managers to make the kind of selfless tradeoffs that realizing a RBPEA requires.”

Yes, I am – though I’m not sure that that’s really the point here?

What I am saying above – and even more in the following post, ‘Idea-parenting’ – is that it’s unwise for organisations to trash the people working on the future, for the simple reason that without these people, trying to deal with the future when it hits is likely to be a heck of a lot harder than it would otherwise be.

The key about RBPEA is that it’s not just about big-picture stuff beyond the corporation “for which most ‘salarymen’ in today’s corporations don’t feel they have the time or latitude”. The big-picture scale is simply an extreme test-bed to cross-check principles that look as if they work at the ordinary corporate-and-within scale, but actually don’t: IT-centrism, for example, or money-centrism. The whole idea is that we take the learnings from the RBPEA analysis in order to apply those learnings in our existing everyday EA-work. That’s why, in most of my RBPEA posts, there’s a section on ‘Implications for enterprise-architecture’: it’s all one continuum, and a lot of the RBPEA insights are very practical and very important for the viability of mainstream, commercial, corporate business-enterprise.

I’m well aware that the big-picture stuff is way outside of most people’s scope. But I’m also aware that when the sh*t really does hit the fan big-time – which, even if we’re lucky, will almost certainly happen within the smaller end of single-digit decades, we’d better darn well be ready for it – otherwise it’s gonna get really nasty, to the level of non-survivability for many, if not most. Kinda important, yes?

Yet since most people seemingly really really don’t want to know about any of that, one way to get them somewhat-prepared, ‘by stealth’, is to give them tools that will not only be useful then, in the not-so-far-future, but also really helpful and really useful right-here-right-now. That’s what this is all about. The catch – and that’s the complaint here and in the next post – is that it’s darn difficult to develop those tools at all, because of the scale of dysfunctionality that we have to struggle against, every single darn inch of the way. I wish it were otherwise, but yes, it ain’t. Just sometimes we have to let off steam about it, that’s all?

@Howard: “Perhaps we will need to be content to nearly-optimize smaller units within larger entities, assuming the external factors beyond the control of the unit management as givens.”

Optimising locally whilst ignoring the larger-scope impacts is a classic (mis)-management error that was fully, openly and urgently identified what, some sixty, seventy, eighty years ago? For example, Stafford Beer and other ‘operations-research’ folks since the 1940s at least; Shewhart and Deming both go back at least to the 1930s; some of the early railway-companies worked this one out on their own back in the 1830s, or not much later than that, anyway. This is an error that managements should know by now that they should not make: getting that point over to management should be fundamental concern for every architect and the like, whatever label they stick in front of the word ‘-architect’.

Tom: I just start reading the book of Jony Ive: “Jony Ive: The Genius Behind Apple’s Greatest products”. Even though the industry design (ID) consultancies have been practiced and well accepted by corporations for many years, the designers contracted to do the work will still have to make concessions most of the time for the final work products they deliver. The executives and the business managers have the final say of what they want. It is a very frustrating experience that the ID designers have to accept and live.

EA often wants to draw parallels from building architecture, but I believe we can learn more from the industrial/product design (ID) practices, because they serve the same customers as EA does and they are a well established profession.

ID is to design a product line or a family of product lines. If EA is about enterprise design, it thus faces a bigger huddle to get the services accepted by the executives. If that is what it aims at, the huddle may be too high, and hence your two words.

Most of the corporate EAers, if not all, work in CIO organizations. When we work for a boss, we work by his priorities. Most of the companies do not want people to innovate things outside of their stragety. Therefore, neither EA consultants nor corporate EAers have much weight to steer the direction.

I have been working on the tooling of handling the domain of RBPEA in your term for a couple of years. Like you said, it is vastly challenging in scale and scope. After many redesigns and recodes, I believe a tooling break through will need the following three things

1. A holistic model of the entire enterprise of many kinds. Not just a collection of many models and architectures we usually list.

2. A mathematical and engineering/technical treatment in handling the complexity of the model

3. A clever and intuitive design of the user interface that connects the EA work products to the daily work life of the executives and managers.

And finally, with the tool, it will still take a disruption in the practices and business for the true EA services to be formally accepted.

Before that happens, EA needs to endure.

@Colin: “I believe we can learn more from the industrial/product design (ID) practices”

Very good point. Milan Guenther’s work on ‘Enterprise Design‘ develops quite a lot on that theme, as I remember?

@Colin: “I believe a tooling break through will need the following three things:” (holistic model, mathematical treatment for model-complexity, manager-friendly user-interface)

Strong agree on the first and last of those three, though I’m not sure what you mean by ‘mathematical treatment’ – some forms of complexity seem unlikely to be amenable to that type of approach?

Do keep me informed on where you get to with that, anyway – I’m very interested.

@Colin: “Before that happens, EA needs to endure.”

Which it isn’t: the IT-centric term-hijack is almost total now, and certainly getting worse by the day (though the absurdity of that term-hijack is becoming more visible day by day, too).

Which means that we need a Plan B – an alternative term for ‘EA’ that is easily understood as the equivalent of what EA should mean, namely the literal ‘the architecture of the enterprise’. We ain’t there yet, but feels like we’re maybe getting a bit closer. The need is clear now, anyway – which it wasn’t even a year or two ago.

What a good reading Tom!

Unfortunately it is with a bit of bitter taste that I have to admit that having being really passionate on EA for at least 20 years, now I feel a sad feeling. My experience agrees with your diagram and especially in the points where money happens and where future work happens. Unfortunately the company metrics and rewards are strongly oriented to the present and as such the perceived value of EA towards the future is completely disregarded. We are all humans and driven mostly by rewards/incentives and penalties/disincentives. The current flavour of work/management style disproportionally rewards the present, very short term and penalise the future. More often than not, the future is only the last powerpoint slide at the end of the deck and it is like the happy ending of bedtime stories.