Seven sins – 1: The Hype Hubris

Enterprise-architecture, strategy, or just about everything, really: they all depend on discipline and rigour – disciplined thinking, disciplined sensemaking and decision-making.

But what happens when that discipline is lost? What are the ‘sins’ that can cause that discipline to be lost? How can we know that it’s been lost? And what can we do to recover?

This is part of a brief series on metadiscipline for sensemaking via the ‘swamp-metaphor‘, and on ‘seven sins of dubious discipline’ – common errors that can cause sensemaking-discipline to fail or falter:

- Seven sins of dubious discipline – introduction to the series

- Sin #1: The Hype Hubris

- Sin #2: The Golden-Age Game

- Sin #3: The Newage Nuisance

- Sin #4: The Meaning Mistake

- Sin #5: The Possession Problem

- Sin #6: The Reality Risk

- Sin #7: Lost In The Learning Labyrinth

- Seven sins – a worked-example

Let’s start with Sin #1, the over-exuberance and ‘This is The Answer!’-ism of The Hype Hubris:

This arises from what we might, in our more polite moments, describe as a triumph of marketing over technical expertise. (There are some other epithets for this that are rather ruder, if often rather more accurate.) It’s not just enterprise-architecture that’s at risk here: pretty much every field of study with a strong subjective or emotional element is plagued by a relentless pursuit of hyped-up glamour in which style takes priority over substance. “Never mind the quality, feel the width!”, to quote the tag-line from an old TV comedy…

Glamour sells, but it isn’t real. Like junk-food advertising, it promises sustenance, but never really delivers, leaving us unsatisfied and wanting more. Yet because the hype seems to be all that’s on offer – or at least all that’s easily available – we can get sucked back into it, again and again. More to the point, we trick ourselves into falling for it, time after time after time. And it’s our responsibility to learn to not do so – to recognise the hype for what it is, and move on.

One friend has a habit of visiting a certain fast-food franchise once every few weeks or so. He complains every time about the difference between the glossy airbrushed adverts and the grey flabby vapidity of the real ‘un-food’. The resultant stomach-ache can last for days, he says.

He insists that he only goes there to remind himself of why he doesn’t go there. He hasn’t yet noticed that he does indeed go there – time and time again…

Fair enough, the hype and the glamour are often the ‘hooks’ that grab our attention in the first place, gaining our interest enough to get us started. But at some point – and preferably sooner rather than later – we need to wean ourselves off the pre-digested junk-food, and get down to the real meat of the matter.

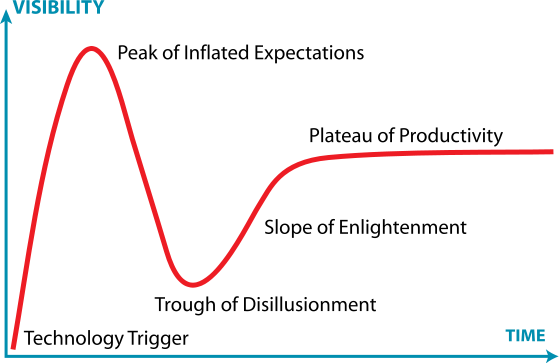

In technology circles, of course, the warnings about this sin are supposedly well-known, as per the infamous Gartner ‘hype-cycle’ sequence:

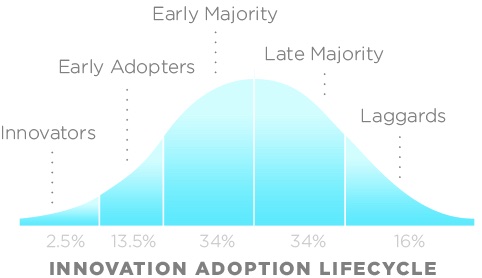

Which aligns well with Rogers et al’s technology-adoption lifecycle:

Which tells us that early-adopters are probably the ones who are most at risk of getting burned by the Hype Hubris. Which, unfortunately, is where much of our work as enterprise-architects tends to reside…

Yet it’s not only the quality of our own work that’s at risk here, because there’s also a darker side to the hype-machine. It’s not just that those who do the ‘boring’ detail-work, often for decades, have almost no way to publish or gain credit for their results: worse, we’ve seen all too many cases where they’ve been misused, plagiarised, derided, then ignored, in a subtle yet singularly nasty form of ‘life-theft’. When rip-off artists are rewarded handsomely for taking us all for a ride, whilst ‘the little people’ who’ve been stolen from are actively penalised, there’s then no incentive to do real work. And when hype is allowed to masquerade as reality, quality suffers, for everyone.

In short, to use the old advertising metaphor, the sizzle ain’t the sausage: the hype can sometimes have a useful role to play, but in itself it isn’t real. So when someone tries to sell us the sizzle, we need to look for the sausage: if the substance isn’t there, it’s time to walk away.

Mapping to ‘swamp-metaphor’ disciplines

To map the above to the set of disciplines for sensemaking and decision-making from the ‘swamp-metaphor‘:

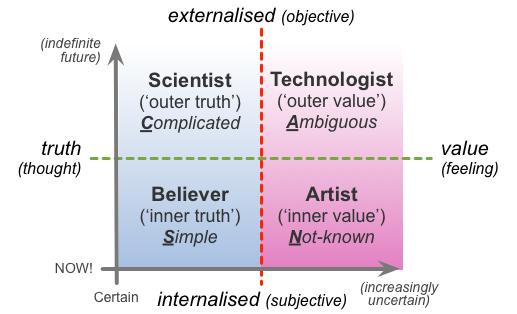

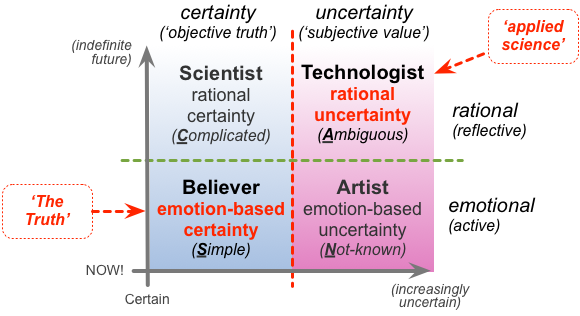

And in turn cross-mapped to the SCAN framework for sensemaking and decision-making:

And also the ‘edges’ or transitions between modes or domains within the dynamics of the sensemaking process:

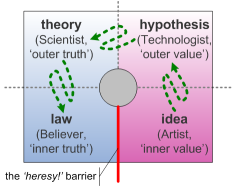

What happens in the Hype Hubris is that there’s first a transition from the Technologist-mode down into the Artist-mode via the edge of innovation, to elicit some new idea or information. There’s then the usual idea-hypothesis loop (Artist :: Technologist) to develop some useful innovation – the hype-cycle’s Technology Trigger.

If the development were to follow the classic science-style sequence of idea-hypothesis-theory-law, the idea-hypothesis loop should be followed by an hypothesis-theory loop (Technologist :: Scientist), to verify and validate everything:

But what happens instead is that the Hype Hubris gets caught up on the ‘applied-science’ mistake, believes that because technology is supposedly ‘applied-science’ it therefore doesn’t need any further testing, and thence does a diagonal jump to the Believer, bypassing the Scientist-mode altogether:

At which point the Believer asserts that it has found ‘The Truth’, ‘The Answer’, and promotes it with all the emotion that it can muster, driving hard all way to the hype-cycle’s ‘Peak of Inflated Expectations’, and meanwhile rejecting everything else as ‘heresy’.

Once the Peak has been reached, reality starts to set in, marked by increasing transitions over the edge of panic, and the hype slowly deflates all the way down to the Trough of Disillusionment – though often with a lot of damage having been done along the way…

At the Trough, the hype is finally broken, and the supposed ‘The Answer’ becomes acknowledged to be, at best, something that might be useful as an answer in certain contexts – the start-point for the hype-cycle’s Slope of Enlightenment. At this point, the Scientist and Technologist are at last allowed back into the picture, to identify where the whatever-it-is actually can be useful, driving steadily upward toward the Plateau of Productivity – where hype is rigorously restrained.

We might note, too, that those who are most susceptible to the Hype Hubris – the more addictive of the Early Adopters – are rarely to be seen at the the Plateau of Productivity. Instead, they’d stopped at Geoffrey Moore’s ‘Chasm‘ – the gap between Early Adopters and Early Majority, that also coincides with the hype-cycle’s Trough of Disillusionment. They’ve have long since rushed back to the start of the hype-cycle again, in search of the emotional high of The Next Big Thing – and, never reaching the Plateau of Productivity on any innovation, will likewise never achieve its real value either. Not A Good Idea…

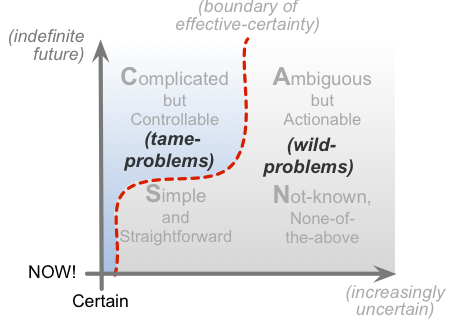

We can also assess the Hype Hubris in terms of tame-problems and wild-problems:

In the Technologist-mode (aligned with the SCAN ‘Ambiguous’ domain), and even more in the Artist-mode (‘Not-known’ domain), everything is contextual, with many wild-problem elements: every innovation has constraints, limits, contextualities, ‘it dependses’ and all of the other uncertainties in the ‘EA-mantra‘.

But to the Believer-mode (‘Simple’ domain) and Scientist-mode (‘Complicated’ domain), everything is and must be certain: everything is, by definition, a tame-problem. Once something works, it is, again by definition, The Truth.

The catch for the Believer-mode is that it must take its assertions and assumptions to be ‘true’ – the whole point is that it can and will take action on those beliefs because it has neither the need nor time to test them. (Testing ‘truth’ is the Scientist-mode’s job, but it needs time to do it – a luxury that isn’t available in real-time action.) Yet the Believer also has to deal with the real-world somehow – and Reality Department encapsulates a lot more uncertainty and wildness than the Scientist-mode would either like or expect. The result is that the Believer-mode gets squeezed, with far more transitions across the edge of panic than the guiding Scientist-mode would either believe or allow. Which leads to a lot of emotional pressure on and in the Believer-mode. Which means that, if we’re not careful about this, something’s gonna give…

All too often, the way out, for the Believer-mode, is to succumb to the Hype Hubris, and let belief take priority over reality: “This is The Answer! anyone who disbelieves is wrong, a failure, will get Left Behind!”. What it doesn’t do is go back to the Scientist-mode to check – because that would risk bursting the bubble of belief. In effect, we end up with not one but two ‘heresy-barriers’: one against testing validity, the other against testing ‘truth’ (in the Artist-mode and Scientist-mode respectively, though both usually in collaboration with Technologist-mode). Instead, it locks itself into a self-confirming echo-chamber, “where seldom is heard / the discouraging word” – and any ‘inconvenient truths’ explicitly excluded until they eventually start to force their way into awareness after the Peak of Inflated Expectations.

Again, it’s Not A Good Idea… – the only way that does work is to allow the dynamics of sensemaking and decision-making to take their natural course, and flow freely between the modes as the context demands.

In summary:

— the Hype Hubris arises from:

- allowing Artist-mode exuberance to overrule the discipline of the Artist-mode itself

- allowing Believer-mode need for certainty and belonging – ‘This is The Answer! I have joined those who know that this is The Answer!’ – to overrule and override Artist-mode dynamics of exploration

— to resolve or mitigate the Hype Hubris:

- go to Scientist-mode to check facts and sources

- cross-check in Technologist-mode by questing and testing usefulness of the ideas and assertions

- acknowledge and mitigate the emotional-needs of the Believer-mode – particularly around fears of facing the Chasm

If we apply those mitigations, we should have a better chance of building a better bridge across the Chasm, between the Peak of Inflated Expectations and the Plateau of Productivity, without having to go all the way down to the Trough of Disillusionment…

Anyway, enough on the Hype Hubris for now: let’s move on to another closely-related ‘sin’ – Sin #2, The Golden-Age Game.

—

(Note: This series is adapted in part from my 2008 book The Disciplines of Dowsing, co-authored with archaeographer Liz Poraj-Wilczynska.)

Without discounting the “need for certainty and belonging” aspect of Believer-mode, I wonder whether speed/convenience (laziness?) might be part of the picture as well.

Yes, it (speed/convenience/laziness etc) is indeed part of the picture, but it tends to be a bit less less prominent in the Hype Hubris than in others of the ‘seven sins’. For example, we see that sloppiness of thinking somewhat in Sin #2, the Golden-Age Game; but where it really comes to the fore is in Sin #3, The Newage Nuisance. More on that in future posts in the series, anyway.