Seven sins – 2: The Golden-Age Game

Enterprise-architecture, strategy, or just about everything, really: they all depend on discipline and rigour – disciplined thinking, disciplined sensemaking and decision-making.

But what happens when that discipline is lost? What are the ‘sins’ that can cause that discipline to be lost? How can we know that it’s been lost? And what can we do to recover?

This is part of a brief series on metadiscipline for sensemaking via the ‘swamp-metaphor‘, and on ‘seven sins of dubious discipline’ – common errors that can cause sensemaking-discipline to fail or falter:

- Seven sins of dubious discipline – introduction to the series

- Sin #1: The Hype Hubris

- Sin #2: The Golden-Age Game

- Sin #3: The Newage Nuisance

- Sin #4: The Meaning Mistake

- Sin #5: The Possession Problem

- Sin #6: The Reality Risk

- Sin #7: Lost In The Learning Labyrinth

- Seven sins – a worked-example

Let’s continue this sad story with Sin #2, the over-certainty and otherworldliness of The Golden-Age Game:

This has its source in what we might gently deride as “a bizarre blend of super-science and super-religion”, but its core symptom is an over-focus on some idealised ‘otherwhen’ – past or future – distracting attention from needs to happen in the real-world present.

In the enterprise-architecture context, the Golden-Age Game would typically occur in a form in which the ‘otherwhen’ is some imagined ‘perfect future’ – all centred around IT, of course, or some other type of technology. (The Singularity folks perhaps come most to mind at this point, though almost every technology-vendor’s hype would fit the bill pretty well too.)

Yet since our work is naturally focussed somewhat towards the future anyway, it can sometimes be hard to spot the syndrome and its symptoms amidst all the other clutter and confusions that we have to deal with. Instead, it’s easier to make sense of what’s going on in the Golden-Age Game if we look for its occurrence in other areas – and one of the best for this is the Game’s all-too-frequent eruptions within certain self-styled ‘New Age’ subcultures, for whom, usually, the ‘otherwhen’ is some imagined ‘perfect past’.

The idea is that somewhere in the distant past – you pick when and where, there’s plenty to choose from – there was just one culture, one civilisation, one faith or whatever, with a special elite class of priest-scientists, separate from mere ordinary mortals, who somehow ‘knew it all’. They’d created the perfect utopia, which is ready and waiting for us now, if only we can find the way…

It’s a lovely dream, perhaps. Yet that’s all it is: a lovely dream. And in most cases its hidden purpose is to distract attention from our real responsibilities in the here-and-now. Which is why, if we’re not careful, chasing that dream can become a serious sin…

There’s no doubt that there is real value in the quest for the ‘Golden Age’: the hope that there can even be such a place – either in the outer world, or within ourselves – is a crucial, essential driver for personal and social change. Yet we need to balance that quest with realism, and with a great deal more honesty and self-honesty than the hype-ridden hagiography of this field will usually allow.

A colleague and I were at a conference in Glastonbury – where else? – where we’d been presenting our concerns on this issue. A well-dressed, middle-aged man came up to us afterwards, exuding self-confidence. “You’re quite wrong, of course”, he boomed, in the rolling, unctuous tones of the much-practised orator, “We know everything about Atlantis and the Golden Age. It’s all in the ancient Hittite scrolls.” A perfectly-timed pause. “Though only the Great Masters can read them, of course.” He offered us an indulgent, supercilious smile, turned, and walked away.

We both sighed, releasing a breath that neither of us knew we’d held, and glanced at each other with stunned expressions on our faces. “I rest my case, perhaps…?”

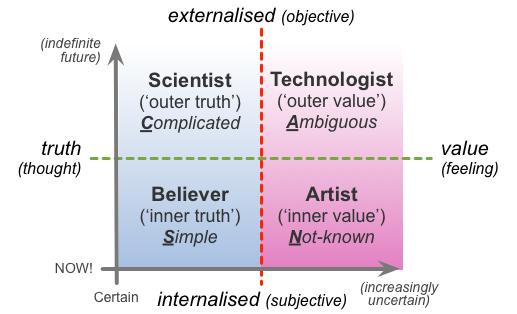

What’s going on here is indeed about ‘super-science and super-religion’ – or more accurately a muddled blurring between the modes of the Scientist and the Believer. The latter needs, above all, to believe in something, deeply, passionately: that’s its role. The Scientist needs concrete facts: that’s its role, too. But in the Golden Age Game, beliefs are treated as fact, and facts are filtered to fit in with the assumptions of the belief. Neither mode is used correctly; and whenever any kind of challenge occurs in one mode, the game jumps across to the other mode whilst still purporting to use the first mode’s rules. “It is fact because I believe it to be true; since it is fact, it is therefore true, hence must be believed by all” – that’s essentially the kind of reasoning that happens there. Round and round the garden we go: no checks, no balances, no questions – and no question of usefulness, either. And behind it, all too often, a subtle unacknowledged arrogance: “we followers of the Golden-Age are also, by definition, members of that special elite, the ‘Chosen Ones’, whilst all other ‘unbelievers’ are not”…

When we do check those claims against real-world analogues that were active throughout those periods of the past, such as Australian aboriginals, or the Amazonian peoples, it’s true we do often find a deep knowledge that can be far outside of what’s known in mainstream techno-scientific culture – which is why drug-companies and others fund expeditions to ‘research’ or, more bluntly, steal as much of that knowledge as they can. Yet that knowledge is also highly contextual – in other words, it lives as much in the Technologist mode as in the Scientist or Believer – and always derives in part from the personal experience and inherent-uniqueness of the Artist mode. And though the respective lore may well have been passed down through an unbroken line of elders or grandmothers – who may well guard that knowledge with care, for reasons of health and safety if nothing else – there’s no real evidence for anything resembling the Golden Age’s beloved priesthood-elites (or, for the future-oriented Golden-Age, technology-elites). Just ordinary people, living their lives in their own particular way, with their own particular, peculiar responsibilities. Just like us, in fact.

The ‘truths’ of the Scientist and Believer modes have no inherent meaning on their own – and especially not when they’re mangled in Golden Age myths. To reach anything that anyone can use, they need to be balanced with the Technologist-mode’s awareness of appropriateness. And as practitioners, we can also use the Artist-mode to find more from sensing within the landscape, for example, than could be learned from a half-imaginary translation of some half-invented ‘ancient scroll’.

So whilst few people would doubt that there are real mysteries yet to be explored, the Golden-Age Game distracts from that deeper exploration. Its purported marvels consist of little more than a handful of past mysteries or future possibilities, taken far out of their real context, contorted by clueless ‘cultural imperialism’, narcissistic nostalgia and self-centred delusions of grandeur, and blown up out of all proportion by wishful-thinking, hype and hope.

More than hope, perhaps. There’s a Welsh word hiraeth that describes this well: woefully mistranslated as ‘homesickness’, it’s more “a longing and grieving for that which is not, has never been and can never be”. We do need to respect that grief: when we look deeply into it, it hurts more than most can bear. Yet building Golden-Age myths to hide from the hurt just does not help. Take that alone-ness, that crushing sadness, and work with it to build something real instead.

There is nowhere else, no-when else, to which we can run away from the perils and problems of the present. If it can be said to exist at all, the only possible Golden Age we can experience exists in what we create, here, and now.

Mapping to ‘swamp-metaphor’ disciplines

To map the above to the set of disciplines for sensemaking and decision-making from the ‘swamp-metaphor‘:

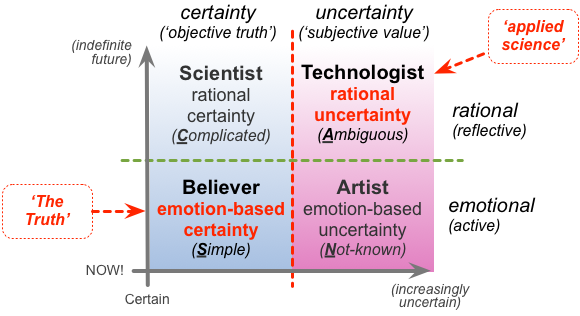

And in turn cross-mapped to the SCAN framework for sensemaking and decision-making:

Unlike in the Hype Hubris, this ‘sin’ is less about poor management of the ‘edges’ or transitions between modes, but more about what is, bluntly, sloppy thinking – persistently using the wrong mode for the respective sensemaking-tasks, and, worse, using the sloppy thinking itself a purported ‘proof’ and ‘justification’ for the sloppy thinking. Not A Good Idea…

As described earlier above, the core emotional driver behind the ‘sin’ is much the same as in the Hype Hubris: fear of uncertainty. In this case, somewhat as in the Hype Hubris, but with even more intensity, there’s also fear of loss of ‘control’ or loss of perceived-status – whether real or self-imagined – and fear of or desire for change in the present. The combination of strong emotion and purported ‘The Truth’ places it firmly in the Believer-mode – and very much anchored there, blocking all further sensemaking.

As with some others of the ‘sins’, the Golden-Age Game is essentially a ‘find the lady’ shell-game or switcheroo with the sensemaking-modes, within which the person being duped is as much the Self as it is any Others. The shell-game uses both of the key mode-errors available in misuse of the model:

The way the shell-game works is as follows:

- a suitable belief is arbitrarily selected (Believer-mode), aligned to the person’s context and emotional needs

- the belief purports to be tested and verified in the Scientist-mode, but solely within the constraints provided by the belief, and with the belief’s assertions imposed as ‘fact’ (i.e. circular-reasoning)

- the validity of the belief, and elements within the belief that are inherently-uncertain (e.g. facts about future or far-past) or that imply value-concerns rather than ‘truth’-concerns, are nominally passed to the Technologist-mode for evaluation – but the ‘applied-science’ error is invoked, imposing Scientist-mode methods on a Technologist-mode sensemaking-context, to purport that these elements are ‘the truth’ and therefore beyond question or doubt

- since all elements of the belief can thus purport to be proven as ‘The Truth’, sensemaking falls back exclusively into the emotional comfort of the Believer-mode, defended by unbreakable and unchallengeable walls of circular-reasoning

One really dangerous variant of the Golden-Age Game that we see all too often in enterprise-architecture and the like – and perhaps especially in the futures domain – is an over-reliance on deus ex machina pseudo-‘solutions’. Deus ex machina is “a plot device whereby a seemingly unsolvable problem is suddenly and abruptly resolved by the contrived and unexpected intervention of some new event, character, ability or object” – or, in a technological context, an assumption that some problem seemingly irresolvable in the present will somehow be magically fixed by some so-far-nonexistent future technology. In effect, it’s a serious form of abuse, “offloading responsibility onto the Other in some ‘otherwhen’, without their engagement and consent” – dumping our problems of the present onto the people of the future, or blaming the people of the past, so that we can avoid facing those problems ourselves.

We also see a more near-future form of the Golden-Age Game, coupled with the Hype Hubris, in the plethora of ‘packaged-interventions’, where it’s assumed that simply inserting some new technology-based ‘fix’ into a societal challenge such as persistent poverty or poor education will magically solve the problem all on its own. As Kentaro Toyama documents in detail in his book Geek Heresy, that just doesn’t work: in fact it usually makes things worse, magnifying rather than reducing any existing disparities or inequalities. Instead, as the book’s description puts it:

even in a world steeped in technology, social challenges are best met with deeply social solutions.

For enterprise-architecture, and even more for the RBPEA (Really-Big-Picture Enterprise-Architecture) level, Geek Heresy is probably one of the best descriptions of what happens when the Golden-Age Game is allowed to run rampant in a sociotechnical context, and what needs to be done instead to sort out the resultant mess. Strongly recommended: in my opinion it should be mandatory reading for all enterprise-architects – perhaps even more so than the omnipresent ‘EA-frameworks’ that themselves probably contribute more to that mess anyway.

In summary:

— the Golden-Age Game arises from:

- blurring between Believer-mode (belief, and desire for sense of belonging to something ‘special and different’) and Scientist-mode (beliefs mistaken for facts)

- desire for, or fear of loss of, presumed ‘priority and privilege’ as one of the self-selected ‘Chosen Ones’

- desire to claim credit and status in the present for work done or to be done by others in the past or future (the purported ‘Golden Age’), without doing the work itself

— to resolve or mitigate the Golden-Age Game:

- maintain clear distinction between Believer and Scientist modes

- balance with Technologist and Artist modes to establish context, meaning and use

- acknowledge and mitigate the emotional needs of the Believer-mode – particularly around fear of loss of social or professional credibility and status

Do remember, by the way, that although it’s always easiest to see these ‘sins’ in others’ thinking, it’s all too likely that we also fall for the exact same mistakes too. The people’s behaviour we most need to watch is our own – not necessarily that of others…

Anyway, that’s probably enough on the Golden-Age Game: we’ll move on now to another ‘sin’ that somehow manages to make even worse mess of everything – Sin #3, The Newage Nuisance.

—

(Note: This series is adapted in part from my 2008 book The Disciplines of Dowsing, co-authored with archaeographer Liz Poraj-Wilczynska.)

Leave a Reply