Seven sins – 5: The Possession Problem

Enterprise-architecture, strategy, or just about everything, really: they all depend on discipline and rigour – disciplined thinking, disciplined sensemaking and decision-making.

But what happens when that discipline is lost? What are the ‘sins’ that can cause that discipline to be lost? How can we know that it’s been lost? And what can we do to recover?

This is part of a brief series on metadiscipline for sensemaking via the ‘swamp-metaphor‘, and on ‘seven sins of dubious discipline’ – common errors that can cause sensemaking-discipline to fail or falter:

- Seven sins of dubious discipline – introduction to the series

- Sin #1: The Hype Hubris

- Sin #2: The Golden-Age Game

- Sin #3: The Newage Nuisance

- Sin #4: The Meaning Mistake

- Sin #5: The Possession Problem

- Sin #6: The Reality Risk

- Sin #7: Lost In The Learning Labyrinth

- Seven sins – a worked-example

And this time it’s Sin #5, the paediarchal pontifications of the Possession Problem:

This is somewhat different from the other ‘sins’, because it doesn’t arise from mistakes with the modes as such, but from another source entirely: ego. And behind that, all too often, are unacknowledged fears that can be surprisingly hard to face…

In essence, the core of the problem is a fear of uncertainty. When the world becomes too complex for comfort, there’s a natural tendency to cling on to what we know, what we have, what we believe, and claim exclusive ownership of all such things. In short, the problem is one of possession – but in both senses, as both possessing and possessed.

In our context here, in enterprise-architecture and the like, we see this most often in two different forms:

- possession as separation – for example, the concept of separation between ‘Us’ and ‘Them’, between ‘IT’ versus ‘the Business’, or between the ‘sacred turf’ of a sports-ground or suchlike versus ‘the ordinary world’ beyond

- possession as possessing ‘the truth’ – evidenced in ‘religious wars’ between different approaches to architecture, different operating-systems, different development-languages, different vendors’ offerings, or whatever

The first trap is that neither places nor ideas are commodities to be possessed: they simply are. And whilst a notion of stewardship does work as a model for ownership of such things, possession doesn’t: it gets in the way, all the time.

(If you’re interested in how the power-issues behind the Possession Problem play out more broadly in business and the wider society, see my book Power and Response-ability: the human side of systems, and the associated ‘manifesto‘ on power in the workplace.)

The problem stems in part from a misuse of the Believer-mode – or, more specifically, a sub-mode of the Believer that we might describe as the Priest. Like the Scientist, the Believer-mode needs certainty in the form of what it calls ‘truth’. But whilst the Scientist-mode gets there by testing and cross-linking everything to everything else, the Believer simply declares or assumes something to be ‘the truth’ – hence ‘to take it on faith’. To get round the problem that some things will inevitably not fit with that ‘truth’, the Believer-mode again simply declares that anything that doesn’t fit is ‘not-true’, and can or should or must ignored. It then places an explicit yet arbitrary boundary between the true and the not-true: hence, for example, that arbitrary separation between the ‘sacred’ and the ‘profane’ – literally ‘pro-fanum’, ‘that which is outside the temple’.

There’s nothing wrong with that in itself – it’s a useful tactic for structuring relationships between things and activities and responsibilities, as we’ll have seen in every organisation. The problem comes when people think that the boundary is real, that the boundary is itself an integral ‘The Truth’ – and try to possess everything inside it. The Priest sub-mode of the Believer not only tries to possess the belief, yet also tries to possess others’ beliefs too, by forcing others to believe likewise – the classic Bolshevist tactic, for example.

The real reason behind this is that the person stuck in the Priest sub-mode can use that ‘possession’ in order to not face the emotional and other stress concomitant on the possibility that the belief may be invalid. And the amount of emotion so often unleashed against ‘heresy’ – which literally translates as nothing more serious than ‘to think different’ – gives us a rather strong clue that it’s not just about ‘truth’ here. In trying to possess the belief, people end up being possessed by it – which is Not A Good Idea…

(The ‘must-be mistake’ that we saw in Sin #4 can likewise be a problem here, because it’s often also an attempt to claim a Priest-like possession of ‘the only truth’.

For example, for members of the Skeptics Society – which, to be blunt, is often little more than a cult-like religion based on scientism – it’s not unusual to claim that if they can reproduce some supposed ‘supernatural’ event by illusionist means, then that must be the way it was done. They appear to believe that this gives them an inalienable right to harass and ‘expose’ all others as purported frauds.

Yet not only is this abysmal as science – the Meaning Mistake – but it’s also extraordinarily abusive, if not violent. As with the Newage Nuisance, this kind of bullying bluster is another all too common characteristic of the Possession Problem.)

We’ve seen some of this already in the Newage Nuisance and Golden-Age Game, of course, but what makes it even messier here is the creation of boundaries that are put up to protect the ‘possession’. Reality as a whole doesn’t have boundaries: pollution takes no notice of national borders, for example. And as enterprise-architects it’s not just the fences and walls around the organisational silos and suchlike that get in our way – it’s the arbitrary separation of things that’s the real problem, because it prevents us from gaining any sense of the whole.

To give an archaeological example, consider large-scale archaeoastronomy (NASA summary [PDF]) at a site such as the Castlerigg stone circle in northwest England. The circle itself is the bit that everyone sees, as the supposed ‘sacred site’. Yet it’s also a kind of local focus – the foresight, so to speak – for a meshwork of sight-lines that could be to identify specific rise and set of sun and moon and stars, as per that respective astronomical epoch of several thousand years ago. But the other ends of each of the lines – the backsights – are the peaks and notches in the mountains all round the circle, miles away into the distance. The central ‘sacred site’ makes no sense unless we consider the entire landscape – circles, hills, valleys, mountains, everything – to be part of the site as a whole. So although it’s true that there are places that act as focal-points in some sense or other, there are no ‘sacred sites’ as such – everywhere is ‘sacred’ to someone, in some context. It’s all one continuum: creating arbitrary boundaries between the ‘sacred’ and the ‘profane’, the ‘important’ and the ‘unimportant’, will just get in the way, not only of action, but of thinking, too.

For enterprise-architects, the same principle applies to the relationships between organisation and enterprise, to the relationships beyond the organisation, to any ‘enterprise of enterprises’ and so on. That’s one reason why I’m so emphatic in warning against the dangers of any form of ‘something-centrism‘ – whether it be IT-centrism, organisation-centrism, money-centrism, customer-centrism, shareholder-centrism or whatever.

In much the same sense, fixed ideas or theories about the past or future can themselves become boundaries to our thinking, preventing us from seeing a context in any other way. ‘The past’ is subjective, not objective: we can’t go there, and there’s very little that we can test in the Scientist sense – we have no way to tell for certain what people thought, how they felt, what they believed. The exact same applies to any notions of ‘the future’: by the time we get there, to have anything that we can test in an objective sense, it’s not longer ‘the future’ – it’s the present. In a very literal sense, both past and future alike are “a different country”: they did and will indeed do things differently there, and often for very different reasons than those that would apply in the present time.

So discoveries in the present do not necessarily ‘prove’ anything about the past, or the future. To link back to the Newage Nuisance, we may well find interesting ‘energies’ or whatever at so-called sacred-sites; to link back to the Golden-Age Game, we may well find extraordinary astronomical alignments and so on; yet that does not mean that any of it was planned by the purported ‘astronomer-priests’ of some mythical ‘golden age’. Instead, from what little we know of the cultures concerned, and from equivalent cultures in the present, it seems more likely that such things arose more from the intuition of the Artist-mode – simply, that ‘it seemed like a good idea at the time’, and was. It’s perhaps more useful, too, to apply the Technologist’s perspective – to ask “what use is it?” – than to fight over ‘truths’ that probably never existed in the first place…

There’s also an academic discipline called ‘deconstruction‘ that can be useful here. Its task is to pick apart each assertion of ‘truth’, so as to surface any hidden assumptions. More useful still is an expanded variant called Causal Layered Analysis which applies the same questioning up and down the layers, from the everyday ‘litany of complaint’ down to the deep myths and core-beliefs. The aim in both cases is to identify notions and worldviews that are somehow ‘privileged’ – assumed to be fact, but without any actual questioning to verify it as fact.

(One catch to watch here is that the same deconstruction must always be applied to the analysis itself, to check for our own hidden assumptions in the way we do it. Kind of mind-bending in its recursion, perhaps, and often personally challenging, too, but it’s something that must be done if the analysis is to be meaningful.

If we avoid this check, our own worldview becomes ‘privileged’ – presented as indubitable ‘fact’, in the classic Possession Problem style – but we have no way to recognise that we’ve done so. The result is usually some pointless exercise in arrogant ‘Other-blame’, with nothing useful that can be achieved at the end of it.

I’ve come across this misuse of deconstruction often in some styles of social and environmental activism, for example, though it’s also common – if in less overt forms – in much ‘New Age’ thinking too. And likewise in enterprise-architecture, if we’re not careful…)

It then becomes useful – if sometimes embarrassing – to ask what worldviews and assumptions tend to be ‘privileged’ in in or our work-domains, enterprise-architecture and the like. The Golden-Age Game is one obvious example, but there are plenty of others – such as the tendency to regard anything supposedly ‘IT-based’ as inherently better than anything else. Or likewise the Taylorist assertion that managers and management are inherently ‘more important’ than any other aspect of organisation – which turns out to be just plain wrong.

So another potent source for the Possession Problem is that, in part because of the nature of the Believer-mode, and under pressure from their respective Priest-mode, each group and enclave will tend to create, and enforce, its own orthodoxy, its own ‘official version’ of ‘the truth’ – frequently deriding anything and anyone else as ‘the lunatic fringe’. Archaeology has a long history of this, for example; likewise medicine, in fact pretty much every discipline with a strong inherently-subjective base. Which, yes, does include enterprise-architecture – especially at larger scope or scale.

What’s interesting, too, is the process by which yesterday’s ‘heresy’ so often becomes today’s orthodoxy, and onward to tomorrow’s passé ‘primitive beliefs’. As Thomas Kuhn showed in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, it’s something of a truism that science will progress mainly by the death of senior scientists – especially those who’ve had a huge personal investment in some particular theory, and will permit change only ‘over my dead body’, in an all too literal sense… In other words, the Possession Problem again.

The best way round this, perhaps, is to take the long view: ‘truth’ changes over time, but quality is real, and lasts forever. And if anyone tells you they own ‘the truth’ about anything, be wary: it’s almost certainly a problem of possession.

Mapping to ‘swamp-metaphor’ disciplines

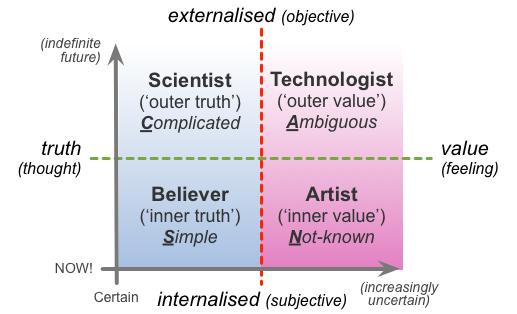

To map the above to the set of disciplines for sensemaking and decision-making from the ‘swamp-metaphor‘:

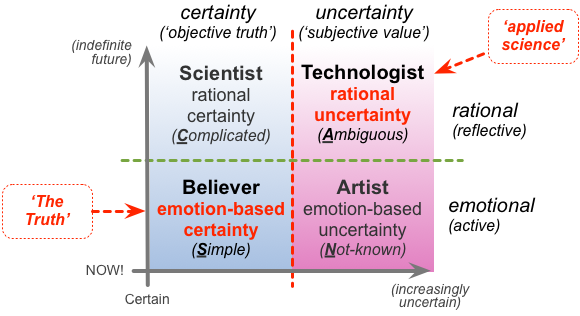

And in turn cross-mapped to the SCAN framework for sensemaking and decision-making:

In terms of that crossmap, what we’re dealing with here is down in the dysfunctional Believer-mode, inappropriately clinging on to its preselected ‘The Truth’:

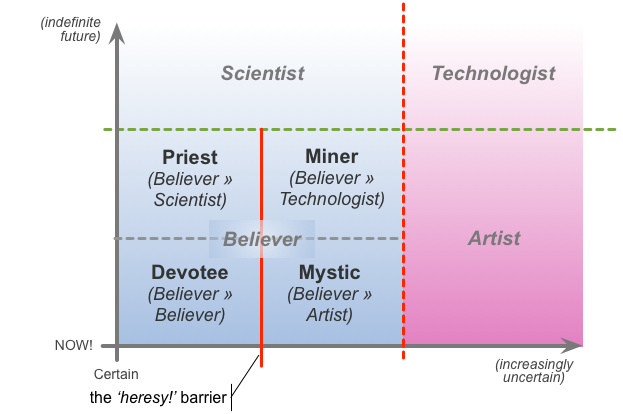

If we apply the SCAN crossmap frame recursively to itself, then within the Believer-mode we can derive the matching four sub-modes:

Or, to summarise each of those sub-modes of the Believer-mode:

- Devotee (Believer » Believer; inner-truth from inner-truth) – holds fast to the selected belief, to apply in action

- Priest (Believer » Scientist; outer-truth from inner-truth) – brings the selected belief down towards action

- Miner (Believer » Technologist; outer-value from inner-truth) – digs ‘downward’ into the belief to find aspects to use

- Mystic (Believer » Artist; inner-value from inner-truth) – extends the belief ‘upward’ to gain new insights

The sub-mode we’re most concerned about here is the Priest. (You’ll find more detail on the other sub-modes in the post ‘Sensemaking and the swamp-metaphor‘.) In essence, the Priest-mode is a Believer that, if it’s not careful, can delude itself into thinking that it’s a Scientist – in other words, mistake its Believer-mode subjective-‘truth’ for a Scientist-mode objective-‘truth’.

To explain why this is so problematic, we need to look a little deeper at how those sensemaking modes work in relation to each other.

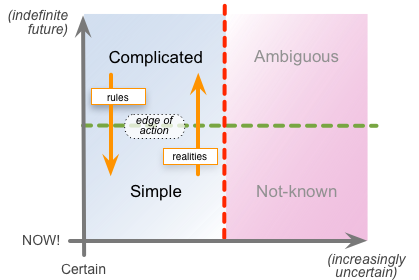

First, let’s go back to SCAN for a moment, and explore the transitions or ‘edges’ between the domains. For the respective domains that we’re dealing with here, that’s the edge of action, between SCAN’s ‘Complicated’ and ‘Simple’ domains:

In our crossmap, the edge-of-action also maps to the edge between Scientist and Believer respectively. Which, following the swamp-metaphor, means that the Scientist-mode will work on rules for the Believer-mode to use; and the Believer-mode will pass back to the Scientist-mode its experiences, so that the rules can be revised as necessary.

(An aside, particularly for anyone of a religious bent: remember that all of this is only a working-metaphor, not a purported ‘fact’. When I describe the Scientist-mode passing instruction to the Believer-mode – or, later below, the Scientist-mode passing instructions to the Priest sub-mode – those terms should not be taken to imply social roles or social priorities, or that religion is somehow inherently subordinate to science. In this context, and unless otherwise explicitly stated, the terms such as Scientist, Believer or Priest are merely labels for sensemaking-modes: nothing more than that.)

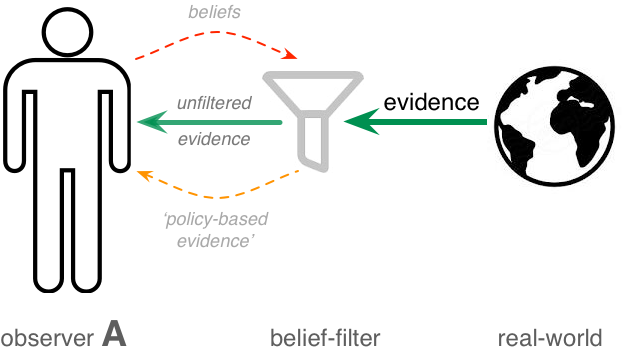

In sensemaking terms, the proper role of the Priest sub-mode is to fine-tune the rules from the Scientist into a form that can be used for the Believer’s specific capabilities that are available at the ‘NOW!’, the exact moment of action. To do this, it filters the full set of rules into a subset that applies for the respective context. For example, we can see this in practice in the relationship between Procedure and Work-instruction in the ISO-9000 quality-standard: there’s a fine-tune stage to adopt the broader principles of a procedure to the detailed work-instruction for a specific machine on a factory-floor. It’s a bit like what happens with mild filtering of real-world information:

…except that instead of real-world evidence, the filtering is applied to the rules and guidance coming ‘down’ from the Scientist-mode.

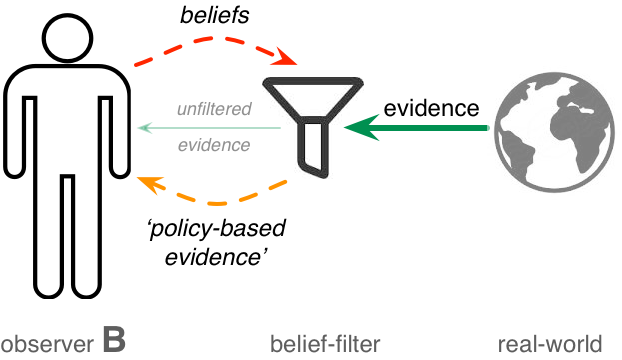

But when we allow our sensemaking and decision-making to get locked in a Priest-mode, we end up running the whole thing the wrong way round. Personal-beliefs – subjective-‘truth’ – come up ‘upward’ as beliefs from the Believer-mode generally, but are reinterpreted as if objective-‘truth’ coming ‘down’ from the Scientist-mode, and then used as the input to the filter. Exactly as with the echo-chamber problem, we end up with self-confirming belief:

…except that, again, rather than highly-filtered ‘policy-based evidence‘, what we get here is highly-filtered rules-for-action, in which the ‘proof’ of the supposed validity of those rules is, in reality, based almost entirely on circular-reasoning. Not A Good Idea…

And yes, it’s worse than it appears (to quote Dave Winer). The Priest-mode sits right up against the most extreme edge of certainty – it’s driven by certainty, and actively rejects anything else. But because it’s the Believer-mode analogue of the Scientist-mode, and the Scientist-mode’s normal role in the sensemaking / decision-making / action loop is to develop and pass rules to the Believer for action, the dysfunctional Priest-mode is an extreme-certainty Believer that is also certain that it has the ‘right’ to impose its beliefs on others. And – because it’s so certain that it’s right – it’s also certain that it has the ‘right’ to ignore any real-world evidence coming from elsewhere in the Believer-mode, or anywhere else at all. This is a key part of what drives the ‘heresy!’-barrier, and why it’s so difficult to break.

(As enterprise-architects, we need to be especially careful not to get locked into the Priest-mode – not least because our work so often has to bridge between different domains of the organisation and more. The dreaded ‘framework wars‘ are probably the classic example here…

For more on this, see the post ‘On sensemaking-models and framework-wars‘ – especially the distinctions between some self-styled ‘guru’s preselected ‘right way to do things’ versus the actual way that works, and ‘three variously-serious problems’ that can impact development and dynamic selection of useful frameworks and metaframeworks.)

The other key driver towards getting locked in the Priest-mode is over-investment of ego in a belief. The danger there is that any doubting of the belief, or its validity, is no longer interpreted just as straightforward critique, a metaphoric ‘threat’ to the belief – instead, it may be interpreted as an existential threat to Self. Hence, again, the ‘heresy!’-barrier – but also a high risk of abuse or violence, to others, or even to Self.

We saw some of the same issues around misplaced-emotion in relation to the Meaning Mistake. The key difference, though, is that in the Meaning Mistake the emotional reaction is almost always ‘hot’: overt anger and suchlike. By contrast, here in the Possession Problem, the emotional reaction, and concomitant abuse of others, usually starts off in emotionally ‘cold’ forms – supercilious, sneering, haughtily shrugging off any doubts about the ‘possessed’ belief, or the purported ‘right’ to possession. If the doubting continues, the response quite quickly switches over to emotional-abuse; and eventually – but often without any warning at all – will launch into full-on ‘righteous’ rage, much more extreme than we’d typically see in relation to the Meaning Mistake. Not fun, for anyone…

From the outside, the Possession Problem might look relatively minor – in fact in most cultures now it’s so much regarded as the norm that it’s almost considered praiseworthy in itself. The reality, though, is that in practice the Possession Problem is one of the most destructive sensemaking ‘sins’ we could fall into – and dangerous not just to ourselves, but often even more so to others as well. As enterprise-architects, we need to be extremely wary of it – perhaps especially in ourselves. Yet another You Have Been Warned item of which we need to take note, perhaps?

In summary:

— the Possession Problem arises from:

- using Believer-mode tactics (“there is only one truth”) in contexts that need Scientist-mode (test and verification of ‘truth’)

- excess of certainty, or fear of uncertainty, leading to inappropriate use of the Believer mode

- excessive investment of ego or Self in any belief

— to resolve or mitigate the Possession Problem:

- balance with the Technologist-mode concept that beliefs are tools, not absolutes

- also use the Technologist-mode to ask “what use is it?” rather than only “is it true?”

- watch for arbitrary boundaries between ‘sacred’ and ‘profane’, ‘Us’ and ‘Them’, ‘mine’ and ‘not-mine’, and so on, and use insights from the Artist mode to create bridges across the boundaries

- use deconstruction and similar tactics to challenge misplaced-possession in all its forms – especially in ourselves

- develop a discipline of low dependency on the purported ‘truth’ of any theory or belief – such as via ‘the EA mantra‘

Let’s move on, anyway – and next on the stack is Sin #6, the often somewhat-strange Reality Risk.

—

(Note: This series is adapted in part from my 2008 book The Disciplines of Dowsing, co-authored with archaeographer Liz Poraj-Wilczynska.)

Leave a Reply