Technology-adoption and time-horizons

This one’s a follow-up to a recent post, ‘Technology-adoption, Wardley-maps and Bimodal-IT‘, which adds the theme of time-horizons for strategy.

The starting-point was a kind Tweet-comment by Ralph-Christian Ohr about that post of mine:

- RT @ralph_ohr Great post by @tetradian on why we have to think tri-modal, rather than dual #innovation – similarities to my model. bit.ly/2a5D0P8

To which Jairo H Venegas sent a quick Tweet-response:

- RT @jairohvenegas: @ralph_ohr we may apply bidirectional bridge H2 to solve the puzzle #3Horizons #Innovation #Strategy cc @tetradian https://t.co/ykxVC2mVF3

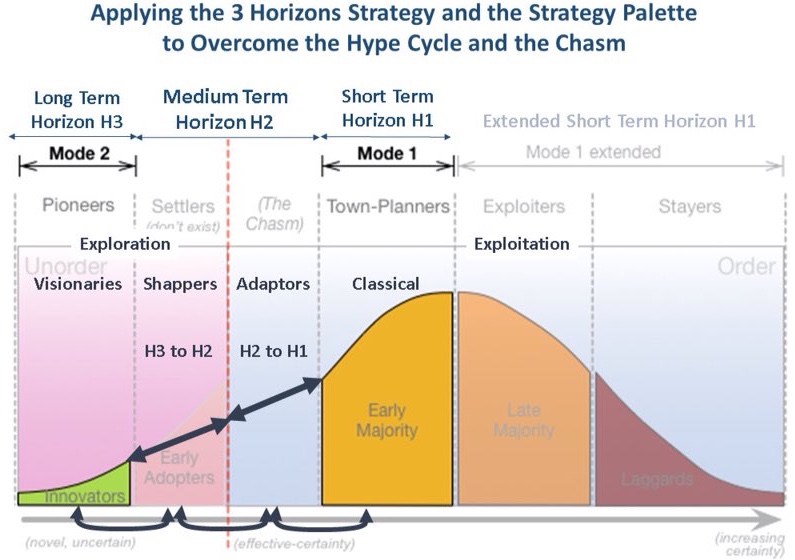

His Tweet points to this modified version of one of the graphics from that previous post of mine:

I’ll admit that at first I just went “What the…???” – and then realised that I needed to do a decent search on ‘3 Horizons Strategy’, because I didn’t have a clue what it was. Oops…

‘Oops’ indeed – I certainly should have known about this one, because it seems to be one of the core models for mainstream strategy:

- McKinsey: ‘Enduring Ideas: The three horizons of growth‘

- Paul Hobcraft: ‘The three-horizon approach to innovating‘

- Tim Kastelle: ‘Linking Innovation to Strategy, part 3‘

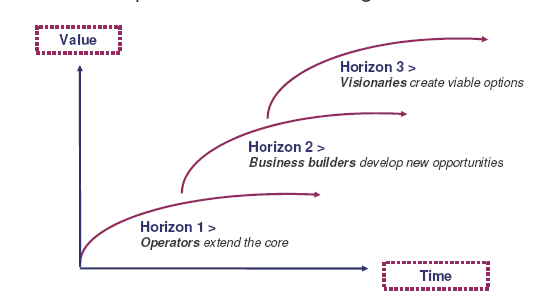

The ‘Three Horizons’ idea seems to have started with a 1999 book, Alchemy of Growth, by Meghai, Coley and White, and is perhaps summarised in its simplest form by this graphic from Paul Hobcraft:

Often there are other tags or attributes put on these time-horizons, and even specific times too:

- Horizon 1: Extend; Current products; Short-term; 0-18 months

- Horizon 2: Build; Next-generation products; Medium-term; 12-36 months

- Horizon 3: Create; Emerging products; Long-term; 24-72 months

But those time-distances in months are all a bit blurry and uncertain, and some writers argue that the horizons should be seen as relative rather than absolute anyway, so we probably don’t need to go into any depth on that.

Which leaves us with Venegas’ four labels and his link-arrows and bridges across the Rogers and Wardley roles.

The labels themselves – Classical, Adaptors, Shappers and Visionaries – do all sort-of make sense relative to each other (though I’m presuming here that ‘Shappers’ is actually ‘Shapers’). Likewise the link-arrows and bridges do (mostly) make sense; and likewise too for ‘Exploration’ with Unorder, and ‘Exploitation’ with Order.

The catch, though, is that the mapping to the underlying Rogers technology-lifecycle doesn’t work – and that kind of invalidates the whole thing…

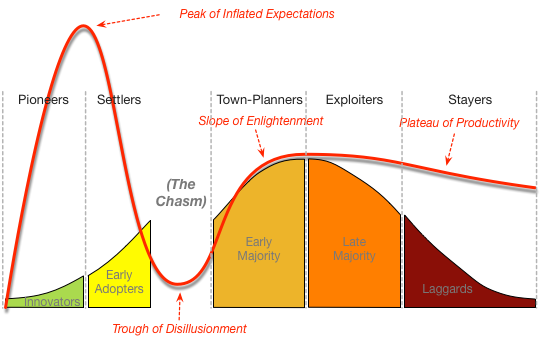

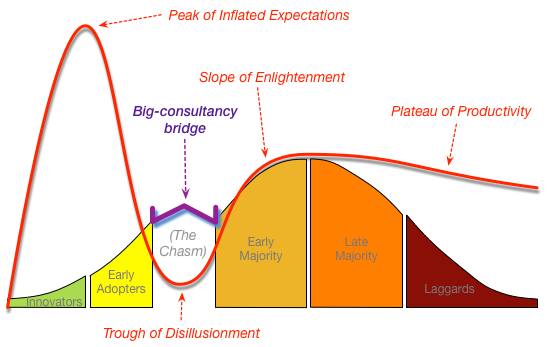

The most obvious problem is that Venegas has placed the Adaptors role in the space denoted by Geoffrey Moore’s ‘the Chasm’. But the catch is that the Chasm isn’t a role – it’s a dysfunctional artefact of a dysfunctional response to the dysfunctional excess of hype developed in the Horizon 3 area, Rogers’ role of Innovators:

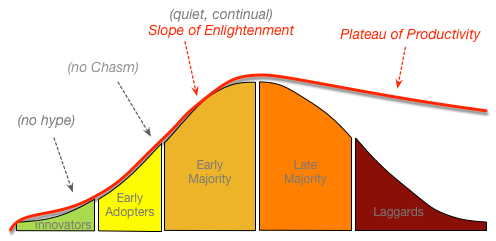

The point here is that if the hype is kept properly at bay, there’s no ‘the Chasm’:

Which, in turn, would mean that if things were done properly, there would therefore be no Adaptors in Venegas’ mapping. Which doesn’t quite make sense.

What also wouldn’t make sense would be to cross-map the Adaptors with the ‘big-consultancy bridge‘ over the Chasm:

The reason why that one doesn’t make sense is that, as explained in the ‘Bimodal-IT’ post, the one thing that the big-consultancies try to avoid having to do is context-specific adaptation – they make their money by putting pre-scripted cookie-cutter ‘solutions’ in place, not point-by-point customisations.

Either way, that mapping just doesn’t work as-is. Sorry…

Another option, though, would be to move the mapping one step further, over on the far side of the (preferably-nonexistent) Chasm, to give us this:

- ‘Visionaries’ : Innovators : Pioneers

- ‘Shapers’ : Early Adopters : Settlers

- ‘Adaptors’ : Early Majority : Town-Planners

- ‘Classical’ : Late Majority : Exploiters

And to me at least, that does make sense. Definitely useful.

The other question is about the time-horizons themselves. Assuming that, as per the other ‘Bimodal-IT’ article, the group we’re really talking about here are the executives who are supposedly responsible for strategic choices. Their natural habitat is in the world infested by the big-consultancies – namely the Early-Majority / Town-Planners space. A key characteristic of this group is that they’re always desperately hungry for The Next New Shiny Thing that might give some kind of competitive-advantage – which is why they’re such easy targets for big-vendor hype – but they’re also deeply change-averse – because they’re supposed to hit their predicted ‘targets’, quarter after quarter, in what is in reality an increasingly-unpredictable world. To be blunt, these are the people who’ve actually killed anything resembling real-strategy in most large organisations. And the one thing they don’t have is a realistic concept of time – or, in particular, of the future, or of futures, with all of its inherent-uncertainty.

Hence, for example, the typical depiction of those time-horizons would be roughly as follows:

- Horizon 3: 24-72 months

- Horizon 2: 12-36 months

- Horizon 1: 0-18 months

- Horizon 0: NOW! to past

(The Horizon 0 maps to the ‘Classical’ group, the Exploiters, the people focussed on ‘keeping the lights on’ and suchlike. Also a more realistic view of how long it takes to develop a new technology could well be five to ten times longer than those periods listed above, but they’ll do for now.)

Yet with those executives, we’re not dealing with a sensible, structured, Rogers-like relationship between distinct roles and responsibilities, each passing the baton from one stage to the next. Instead, to be blunt, in too many cases we’re dealing with people who have the distractability of a two-year-old hyped-up on red food-dye, and – if we’re lucky – an attention-span that’s maybe as much as that of a gnat. And their concept of the Three Horizons would usually be – at best – something more like this:

- Horizon 0: forget it, it’s Somebody Else’s Problem

- Horizon 1: current quarter

- Horizon 2: next quarter

- Horizon 3: whenever the next annual planning-cycle might be

In other words, their notion of ‘Horizon 3’ wouldn’t stretch out even halfway towards any ‘normal’ Horizon 1, let alone towards anything more realistic. There’s no way that a real-world technology-adoption lifecycle will even begin to make sense for a mindset like that. And yes, these are the people who are supposedly in charge of ‘strategy’ in most large organisations – the kind of people who seriously believe that “Last year plus 10%” is a genuine strategy.

Yeah. Ouch…

So the short answer to all of this is that yes, Venegas’ mapping is definitely nice, and clever, and pretty, and maybe even useful for crazies like us in enterprise-architecture and the like. Yet right now, exactly as with so much of my own work, it’s unlikely to help much, if at all, with the people who really need to understand and act on what that mapping says – namely those so-called ‘strategic’-executives. And the reason why it won’t help is that they just won’t get it. Not just won’t get it, but can’t get it; or even more, dare not get it – because their status, jobs, income and bonuses. in so many cases, will depend on not-getting it, but in focussing instead solely on the supposedly-‘controllable’ short-term.

So whilst Venegas is not ‘wrong’ as such, I don’t see any easy way out of this one. There’s a thin chance that some of those executives might eventually start to understand some of the more accessible types of practical tools, such as Wardley maps; I’m hoping that I might soon be able to add some of my tools such as SCAN and SCORE into that category too. But the reality, I fear, is that the only thing we can do is wait it out, in the same bleak sense that it’s sometimes said that “science proceeds by funerals” – maybe not literal funerals as such, in this case, but at least until evolution takes enough of a toll amongst the short-termist dross. Whether any of us can afford to wait that long is another question, of course…

Oh well.

Comments, anyone, perhaps?

Thought-provoking integration of ideas, Tom – thanks for mention and picking this issue up!

I definitely need to mull over your thoughts. For the time being, I thought it may be helpful for you and other readers to point to a book excerpt where the terms “Visionaries”, “Shapers” etc. incl. their contexts were originally introduced: http://media-publications.bcg.com/pdf/Your-Strategy-Needs-a-Strategy-chapter-01.pdf

Many thanks for that, Ralph – would value your comments on this.

(Have duly downloaded your paper – thanks for that! – will read properly as soon as sanity permits… [am at a conference in Copenhagen for the next few days].)

Hi Tom,

We cross pathways again, been a little while. What else can that creative, fertile mind of yours think through some more on the 3H if y<ou pick up on Steve Blank's creative thoughts of linking the BM to the 3H- Known (h1), Partially Known (h2) and Unknowns (h3), layering in Lean Management in H2 & H3 and Process Management in H1.

Start here: https://steveblank.com/2015/06/26/lean-innovation-management-making-corporate-innovation-work/

Await some further Tom thinking

Takes for the article Tom. Insightful as always. Just one left-field point. It seems your first diagram suggests a contradiction of the second law of thermodynamics… :-). Perhaps there is an increasing disorder in the market over time that offsets the increasing order you suggest in your diagram?

Entropy, ah, entropy – you’ve touched on an old firestorm here, Darryl… 🙂 – see ‘Reframing entropy in business‘ and ‘More on reframing entropy in business‘.

A lot of people regard my position on entropy as completely wrong and back-to-front, but it does exactly follow the logic of the Rogers model. In essence, the final stage is most-ordered – not least-ordered. This is because the final stage has reached its own order, from which no amount of force applied will be able to shift it – which is what many people describe as ‘disorder’ but is more accurately ‘extreme self-order’. It’s significantly from the ‘order’ in the middle stages, which is the kind of order that we can use and that we think we can ‘control’. Hence the sequence in effect goes from unorder (potential for useful-order) to useful-order (what most people call ‘order’) to non-useful order (what those people call ‘disorder’).

To link the cycle back from ‘disorder’ to unorder, we need to intercept the entropy accumulation at least somewhat before the final stasis, and shake it up a bit, or catch it at just the right moment, to split it into components that can be reused in a different way. This is actually the same counter-entropy trick that all living-systems use to keep individuals or whole species alive – though to describe that one will take a lot more time and space than I have available here! 🙂

Hope that makes some sense, anyway?

Thanks Tom. Yep, that makes sense. I think scale has a part to play in this conversation as well, but let’s not go there. I’ll end up talking about Chaos Theory, and I’m already out of my depth! 🙂

Great take Tom, thanks for the comments.

The challenge here is to bring these concepts to the daily practice of decision makers including Board and C-suit members, those genuinely compromised and involved in extending the lifespan of their organizations beyond short term results.

I think that tools exist for that purpose, for illustration I point to my ‘Innovation Kaleidoscope’

https://twitter.com/jairohvenegas/status/768195574566903808

that links organizational Ambidexterity, 3 Horizons, and the strategy palette with management styles underlining the directional role of instilling longevity into organizations by simultaneously exploiting existing business while exploring new business along time horizon.

Both exploitation and exploration are equally important, challenging and apparently contradictory because entail different mindsets, business models, organizational set-ups, incentives, initiatives, and KPIs just to name a few critical elements.

Thanks, Jairo. That’s definitely a useful model – do you have a text-based description as well as the graphic?

“Both exploitation and exploration are equally important, challenging and apparently contradictory because entail different mindsets, business models, organizational set-ups, incentives, initiatives, and KPIs just to name a few critical elements” – yes, exactly. And that’s the challenge, isn’t it? 🙁 🙂

I probably need to write yet another blog-post on this, to answer the point that both you and Darryl bring up here, about entropy and the confusions around unorder, order and disorder. It actually does go the direction stated in the diagram here, from unorder to order, with what’s commonly called ‘disorder’ actually being the most extreme form of order, a final self-organised stasis. More later on that, anyway – but thanks again for doing that diagram that you put up on Twitter about this.

Great discussion. In addition my take: From an innovation/strategy point of view, I prefer to draw on a threefold mapping, as outlined here: http://integrative-innovation.net/?p=1157

Whereas H1 fully relates to exploitation (i.e. operations and commerzialization phase), H3 entirely maps onto exploration (i.e. discovery and validation). H2 can be considered a “bridge” that is mostly missing in the innovation practice – encompassing scaling new ventures up and closing the gap (or “chasm” or through of disillusionment) towards established day-to-day business, in terms of market as well as internal adoption. As mentioned nby Jairo above, all three phases or horizons pose dedicated requirements, and address particular types of people – both adopters and internal innovation resources.

From my experience, this mapping goes well with the corporate practice, since H1 and – meanwhile fortunately – also H3 are usually addressed by corporate activities. However, in most cases no systematic scaling activities are factored in – entailing lots of activities but lacking impact or market success.

After mulling over this for some time, I have some slight reservations against mapping three horizons one-on-one onto the strategy palette. The main reason can be taken from the referenced excerpt in my previous commment: while the adoption life cycle refers to market acceptance and innovation maturity, the strategy palette defines dedicated strategies for “archetypical” environments. Even though I found the idea compelling at first sight, I’m not sure a one-on-one mapping is valid, i.e. in my opinion exploration doesn’t necessarily has to start off with a visionary approach/in a predictable and malleable environment and exploitation doesn’t necessarily have to come down to a classical approach operating in a predictable and non-malleable environment.