A simpler SCAN

The SCAN frame provides a simple means to make sense of complexity and decision-making in almost any context. Yet is there perhaps an even simpler way to describe the principles and practice behind it?

I’ve been nibbling at that question for quite a while, and it’s now gotten to the point where it’s probably worth describing what I’ve come up with so far.

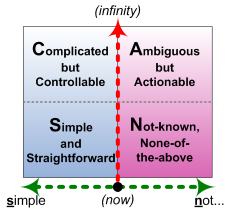

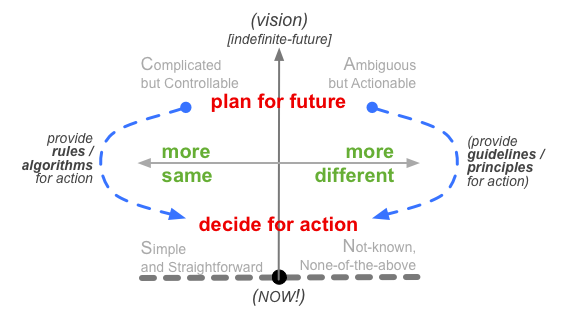

To start with, here’s the sensemaking-version of the usual SCAN frame:

It shows the boundary-conditions: the ‘Inverse-Einstein boundary’ between doing the same thing leading to same results (left) versus different results (right); and the transition from ‘rational’ or ‘considered’ decision-making at distance from the point-of-action (above the horizontal-axis) to emotion-based decision-making close to or at real-time (below the axis). It shows the ‘domains’ implied by those boundary-conditions: Simple, Complicated, Ambiguous, Not-known – hence SCAN.

It works well, and provides a useful focus for cross-comparison with all manner of other ways to make sense of a context. Yet it doesn’t really describe what those distinctions look like in practice.

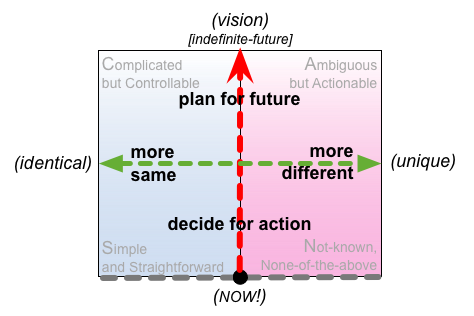

So let’s focus instead on what happens along each of the axes. Which gives us something more like this:

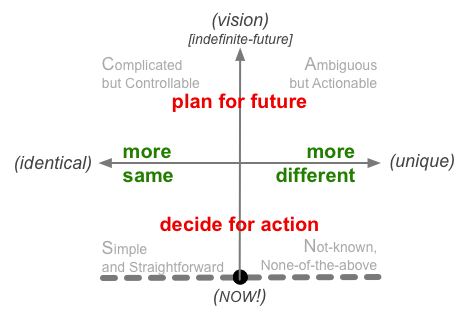

Or, even simpler, like this:

In effect, we’ve changed the emphasis from boundary-conditions (vertical and horizontal) to the spectra (horizontal and vertical) that extend either side of those boundary-conditions. In other words, the actual axes, rather than the effective boundaries that occur (and often move, dynamically) along those axes.

[It’s the same frame, giving us the same implied ‘domains’ in the same relative positions: it’s just a different way of looking at it, that’s all.]

Between sameness and uniqueness

Either side of the Inverse-Einstein boundary, we bounce back and forth between same and different:

- the extreme of sameness is when everything in scope is exactly identical

- the extreme of difference is when everything in scope is utterly unique, sharing no sameness with anything else in that scope

In between, everything has its own distinct mix of sameness and uniqueness.

And the catch there is that methods that assume sameness – as most IT-systems still do, for example – may not work well, or at all, with any kind of difference. Conversely, methods that assume that everything’s unique tend to be very difficult to scale. (See the post ‘Scalability and uniqueness‘ for more detail on that.)

The range and mix of sameness and difference has very real impacts on system-design:

- conventional rule-based machines and IT enable high scaling of sameness, but in practice will often struggle even with small degrees of difference

- humans can handle increasing levels of difference, dependent on skill, but on their own can only work at a human pace

Any system that needs high-scalability (handling large numbers of items at speed), and must also cope with medium to high levels of variation and difference in those items, will usually need a mix of automated and ‘manual’ processes – and the ability to detect when and how to switch between those processes, as appropriate, in accordance with the level of difference and the skill-levels of the people working within those processes.

Note that the real-world always contains a mix that encompasses the entirety of that spectrum, from identical to unique. And since ‘control’ inherently relies on repeatability, which in turn relies on assumptions of ‘sameness’, no automated system will ever be able to provide complete ‘control’ in any complete real-world context. In practice, the illusion of ‘control’ is provided – or propped up – by artificially-imposed constraints on what is considered ‘real’ and what is not, or what is considered ‘in scope’ or not. However, those constraints do not remove the uncertainty: it’s still part of reality, hence still always exists, regardless of those artificial constraints. When difference from the real-world breaches those arbitrary constraints – which, by definition, it must do at some point – then the illusion of ‘control’ that underpins the design of the system will be shattered, and the system itself will fail. No matter how desirable ‘sameness’ and certainty may be, difference and uniqueness are a fact of life: hence we always need to be aware of and design for that fact – and not pretend that it doesn’t exist…

From plan to action

In the other direction, the vertical-axis in SCAN, we work with the tension between the difference between what we plan to do versus what we actually do.

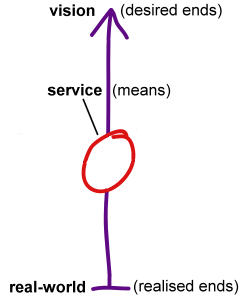

In many ways, this is the same tension as that between desired-ends and realised-ends that, in Enterprise Canvas, underpins and provides the ultimate motivation for any service:

Moving ‘upward’, the vertical-distance here represents effective ‘distance in time’ from the point of action – the moment at which all previous decisions and plans are enacted, applied into real-world action. Or should be enacted, rather, because the reality is that often they’re not: there can sometimes be a very large gap between what was intended, versus what is actually done at the time.

The point here is that there’s another very real boundary somewhere along this axis, driven largely by the fact that the real-world won’t sit around and wait for us to make up our minds what we’re going to do.

This applies to everything: not just to people, but to machines and IT-automation too. Whichever way we do it, there will always a somewhat-tortuous trade-off between speed and complexity: there will always be real constraints on just how complicated any ‘control-law’ can be, even for the fastest of real-time automation.

For rule-based machines and IT, the effect is that we’ll usually have to work out all of those complexities and complications at some distance away from real-time, through analysis and experiment. We then repackage those understandings into rules and algorithms that are compact enough to run at real-time – a translation from Complicated to Simple.

It’s sort-of the same for real-people, though one important difference is that, given sufficient skill, people can also tackle inherent-difference, often all the way to inherent-uniqueness, in real-time action. Decision-making for the latter is supported by guidelines and principles – a translation from Ambiguous to Not-known, something that few machines or IT-systems can handle. Again, these guidelines and principles are developed via analysis and experimentation, at some distance in time from the real-time action.

The aim is that the plan for the future translates as directly as practicable to decisions for real-time action – though the paths to do this translation can vary somewhat, mainly dependent on whether we’re dealing with real-time sameness (‘Simple’) or difference (‘Not-known’). We can summarise those two types of ‘translations’ in visual form as follows:

The real complication here, though, is that, for humans, decision-making at or close to real-time is fundamentally different to that that’s used in most ‘considered’ decision-making: real-time decision-making is primarily emotional, not ‘rational’. For humans, that transition between decision-mechanisms is the core boundary-condition along this vertical-axis of distance-in-time.

Those emotion-based decision-mechanisms are capable of handling only very limited numbers of choices or options in real-time. In practice, the typical limit is somewhere around five to nine options – dependent on a wide variety of factors that I won’t detail here. This is one of the key reasons why action-checklists and sets of principles for real-time use need to be constrained to no more than that size: too many options tends to trigger either a shutdown, a total stop, or a breakdown into what is colloquially described as ‘chaos’ or ‘panic’ – neither of which lead to viable response to the respective conditions.

(Yes, I do know I’m over-simplifying here – but the aim is to keep the description as simple as possible, after all! 🙂 )

Summary

This simpler version of SCAN has essentially the same two axes as before, but with (I hope!) more easily-understood descriptors:

- modality (horizontal-axis, vertical boundary): towards more-same and identicality, or towards more-different and uniqueness

- distance-from-action (vertical-axis, horizontal boundary): from plan-for-the-future to decide-for-action, linking between the vision for the context (indefinite-future) and the real-time NOW!

I hope that makes SCAN even easier to use, anyway. Comments, anyone?

0 Comments on “A simpler SCAN”