What’s the scope of a business-model?

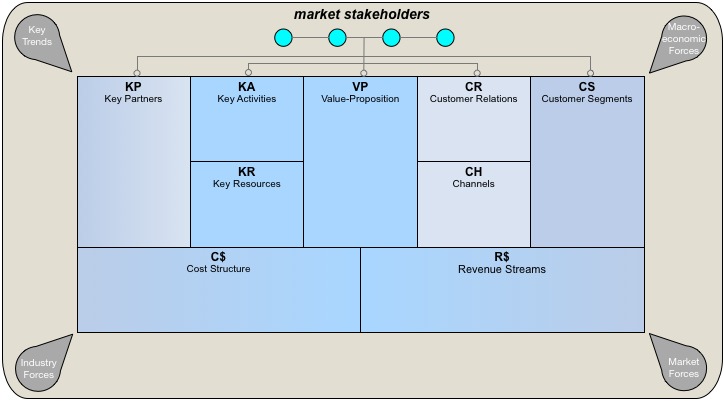

I’ve long been a fan of Alex Osterwalder’s work. There can be no doubt that he’s had a huge impact on business-architecture – particularly for startups – with tools such as his Business Model Canvas [BMCanvas] and, more recently, Value Proposition Canvas [VPCanvas].

And…

(I’d prefer to use ‘And’ here, not ‘But’ – because there’s nothing wrong as such with any of his work, for what it was originally intended to do. Unfortunately a lot of us do often need to move beyond those initial constraints…)

And… there are some significant gaps and ‘gotchas’ that we probably do need to address – particularly when we need to apply that work in the broader realms of business-architecture and beyond.

For our purposes in enterprise-architectures and the like, the two main concerns would be these:

- Costs and returns are described solely in monetary terms – which means, without adaptation, we can’t really use the tools for anything other than the monetary-oriented aspects of commercial-organisations only.

- Although there’s some mention of ‘zoom-out’ to broader context, and ‘zoom-in’ for finer-detail, there’s not enough guidance to provide the full detail that we’d need for real-world implementations and crosschecks.

(There’s another important concern around why the standard description of BMCanvas has not been a good fit for existing organisations, rather than startups, but let’s leave that for another post.)

We can look at both of those concerns somewhat in parallel, using a cross-reference to ideas and principles from the Enterprise Canvas framework. (Enterprise Canvas tackles similar concerns to BMCanvas, but Enterprise Canvas is aimed more at enterprise-architecture and beyond, whilst BMCanvas is optimised for business-models and business-architectures.)

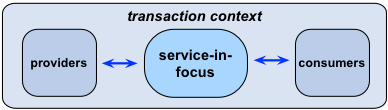

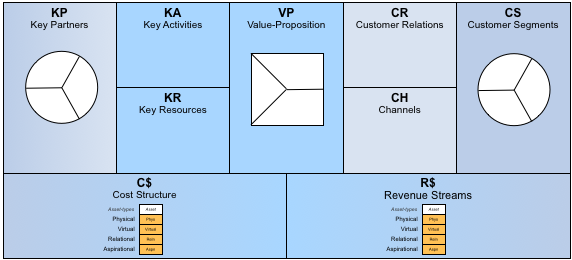

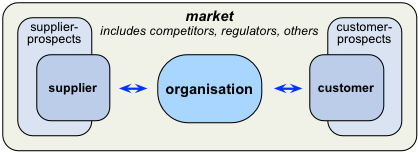

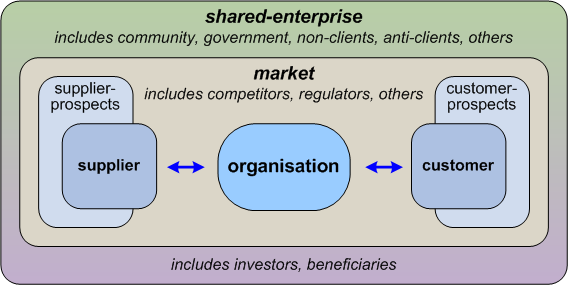

Let’s start with a colour-coding that’s part of the Enterprise Canvas ‘market-model’, indicating the organisation for which we’re doing the business-model, and its respective customers and suppliers:

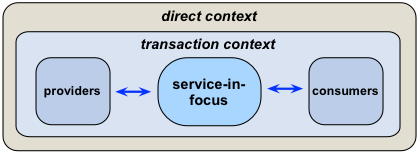

We then add another colour to indicate the immediate transaction-context, including the elements that would be described as ‘Channels’ and ‘Customer Relations’ in BMCanvas:

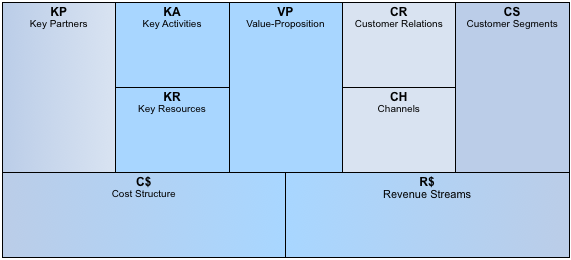

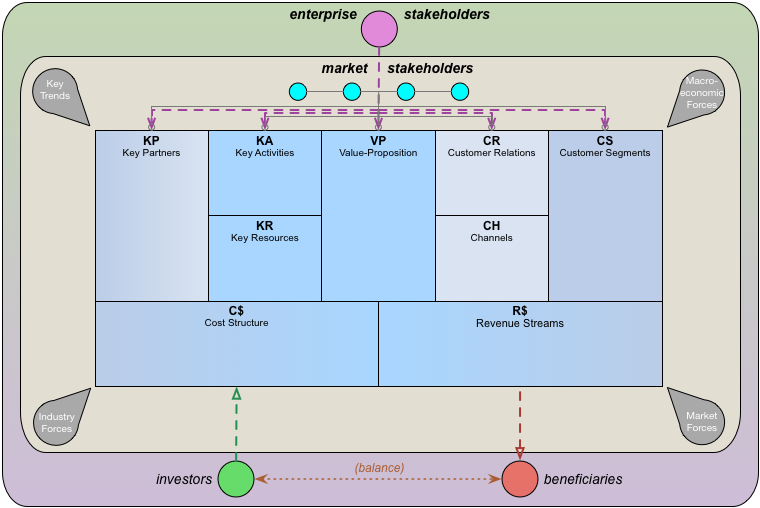

If we then apply that colour-coding to the standard BMCanvas, this is probably what we’d get:

We do have to apply sort-of transitional-tints in a couple of places:

- ‘Key Partners’ encapsulates both the partners themselves (usually as suppliers / providers) and the channels and relations via which we connect with them

- ‘Cost Structure’ and ‘Revenue Streams’ are part external (where value-flow comes and goes) and part internal (what we do with the value-flow)

But it works well enough to illustrate the point – that we can meaningfully link BMCanvas and Enterprise Canvas in this way.

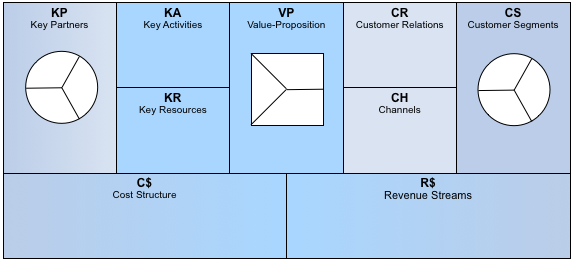

For one aspect of the detail, we need to zoom-in. To do this, the only tool offered for BMCanvas at present is VPCanvas, which consists of two parts – the Value-Map, which goes in the ‘Value-Proposition’ cell of the Business Model Canvas, and the Customer-Profile, which goes in the ‘Customer-Segments’ cell:

(For the detail on these two elements of the VPCanvas, and how to use them, see Alex’s book Value Proposition Design.)

A few moments’ thought should indicate that, in essence, exactly the same applies on the supply-side of the business-model, the ‘Key-Partners’ cell. Because of the way that partners, relations and channels are all blurred together somewhat in this cell, it’s a bit messier to apply the Value-Proposition Canvas directly there, but we can at least apply the Customer Profile to our requirements and needs, to explore our own ‘pains, gains and jobs-to-be-done’:

So far so good. But here we hit against that other concern, that in BMCanvas, costs and returns are described solely in monetary form. It’s a common enough mistake to make in business, but unfortunately it is a mistake, and it’s one that must be resolved if we want, for example, to use BMCanvas for ‘not-for-profit’ organisations, or even to understand the real meaning of ‘value-proposition’.

To illustrate the point, note this definition that’s shown in very large type on p.14 of the Business Model Generation book:

A business model describes the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers and captures value.

Yet on the very next page, if in normal text-type, we get a different definition:

a business model … show[s] the logic of how a company intends to make money.

The catch is that ‘value’ and ‘money’ are not the same: for example, there’s a very big difference between ‘value for money’ and ‘value is money’. Even at best, money is merely a symbol or indicator of perceived-value. And once we move beyond the most simplistic levels of the business-model, it’s absolutely essential not to treat ‘money’ and ‘value’ as synonyms.

Which is a problem here, because that’s exactly what BMCanvas does in its ‘Cost-Structure’ and ‘Revenue-Streams’ cells: it describes costs and returns solely in monetary terms – rather than the value-flow terms that we actually need in order to map out and literally ‘validate’ a complete, implementable, testable business-model.

To make it work, we need to go back to that initial definition of ‘business-model’: “A business model describes the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers and captures value“.

Value.

Not ‘Money‘.

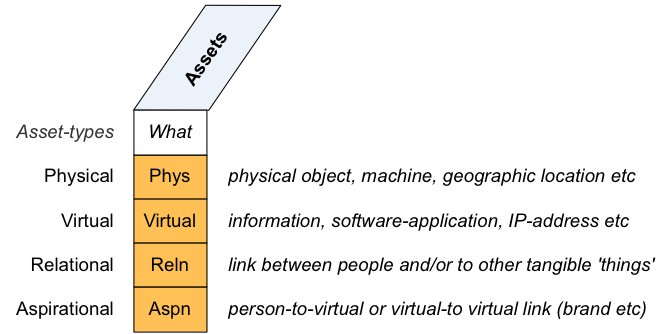

In Enterprise Canvas, we typically map value-flows in terms of a set of asset-dimensions – physical, virtual, relational and aspirational. (There’s more detail on this in posts such as ‘Services and Enterprise Canvas review – 6: Exchanges‘ and ‘Fractals, naming and enterprise-architecture‘.) In effect, ‘value’ is always associated with the ‘aspirational’ dimension – but because of the way the the asset-dimensions interweave with each other, it’s generally best to map those dimensions together as a unified whole:

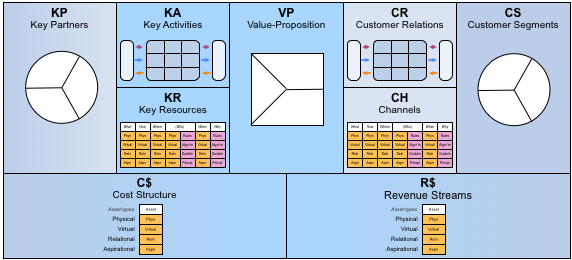

And that’s what we need to track in the ‘Cost-Structure’ and ‘Revenue-Streams’ – value-as-value, not ‘money-as-arbitrary-depiction-of-perceived-value’:

If we focus only on money in those two cells, it’s impossible to describe a meaningful business-model for anything other than a commercial ‘for-profit’ organisation – and even then, the business-model would be missing key elements, as we’ll see later. Yet once we shift the attention there to value in the generic sense (of which money, yes, can be considered to be one possible subset, yet only one subset), then we can use the same framework to describe a business-model for any type of organisation in any context: commercial, government, research-unit, charity, social-club, whatever.

(The overall context within which the organisation operates – the respective shared-enterprise – determines what ‘value’ is within that context, and hence the value-costs and value-returns that we need to track in those two cells. More on that in a moment.)

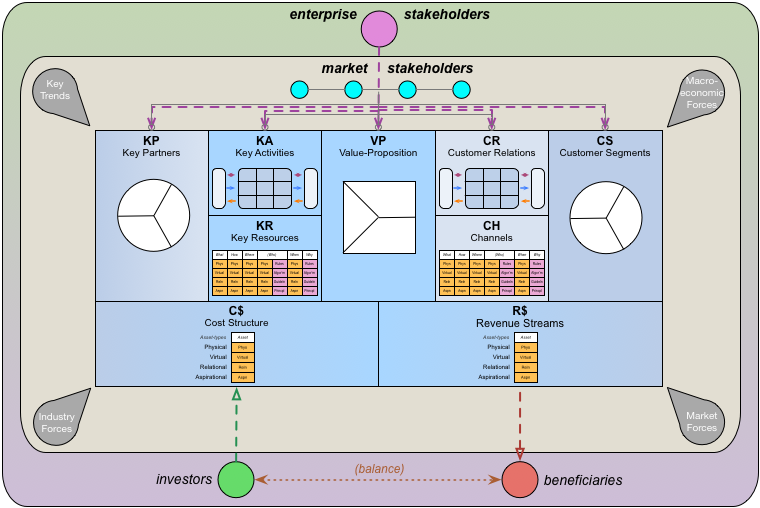

To complete the zoom-in, we’d need to apply other models or views to each of the cells in the BMCanvas:

For simplicity’s sake, I’ve shown above just a couple of standard Enterprise Canvas views (‘service-core’, and ‘service-content’) for the other cells – ‘Key-Activities’, ‘Key Resources’, ‘Customer-Relations’, ‘Channels’. In reality, though, we might need to use any or even all of the thirty or so tools even within Enterprise Canvas, and probably any or many of the hundreds more from elsewhere that are typically needed as we go deeper down into domain-specific detail.

And the whole thing is fractal anyway: we may need to keep zooming-in, and zooming-in again – elements nested within elements, and interacting with other elements, almost to infinity.

In short, the BMCanvas/VPCanvas combination is a very useful simplification, yet we need always to remember that it’s only a simplification – and that sometimes, to understand what could make or break a business-model, we do need to be able to do a dive right down into the depths of the detail.

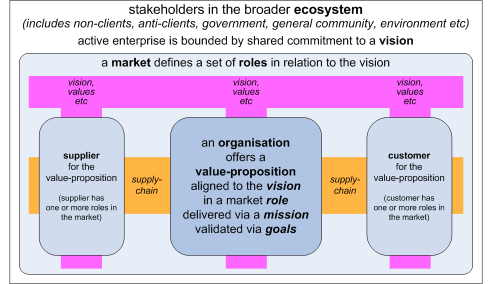

One key part of this where BMCanvas/VPCanvas get it exactly right is that the value-proposition is central to the business-model. The catch, that too many people seem to miss, is that the notion that “value-proposition is the fancy name for your products and services” (to quote Steve Blank) is fundamentally misleading, even just plain wrong. Instead, the value-proposition is how you propose to deliver value to the entire shared-enterprise – not just to you and/or your customer, but to and/or for every stakeholder in that overall context.

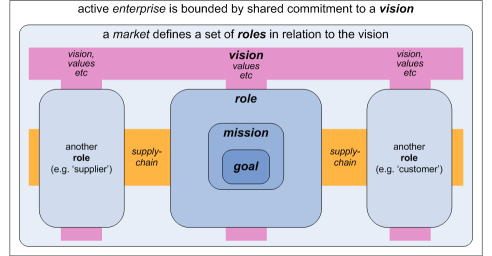

The bit that’s missing from the BMCanvas/VPCanvas pairing – and that, if we’re not careful, can cripple the business-model in seemingly-‘inexplicable’ ways – is that a business-model is not just about value-flow between provider and consumer, and thence the possibility of extraction of some of that value-flow as ‘profit’. In addition to that ‘horizontal’ flow of value along the supply-chain, there’s another whole dimension here, a kind of ‘vertical’ anchor of shared-vision and values that link all the various players together within a shared-enterprise:

The vision and values of the shared-enterprise define what value is within that overall context, along with the relative priorities of those respective forms of value. The value-proposition connects the organisation to its customers, suppliers and others, via its reference to those values – and compliance to those values, too. In most contexts, we’d typically choose to work with only a subset of those values – yet it’s always in context of the whole. In that sense, for a commercial-organisation, monetary-profit – and, in particular, continuing monetary-profit – is a side-effect of “how [that] organization creates, delivers and captures value” for the shared-enterprise as a whole.

To make sense of this, though, we’ll need to zoom-out from the root-level BMCanvas / VPCanvas. This is somewhat described in the respective books, but in most cases we’ll need to go further – often much further – than is summarised there.

To illustrate this, let’s use a painfully real-world example – the business-model for a drug-pusher.

We start with the plain BMCanvas/VPCanvas pairing:

It’s really easy to map out the basic business-model for our drug-pusher. Using VPCanvas, we can map out the customer pains and gains and ‘jobs-to-be-done’ – party-time, perhaps, or relief from loneliness or even life itself; we can describe our ‘value-proposition’ in terms of the products and services we could deliver to resolve those needs; we can summarise and test the fit between our products and various customer-needs. With the rest of the BMCanvas, we can outline the key partners, activities, resources needed, channels, customer-relations. And we can estimate the monetary costs; the probable revenue returned; and the profit from subtracting the one from the other. Profitable indeed. Very profitable…

Except it’s not quite as simple as that, is it?

(Fortunately…)

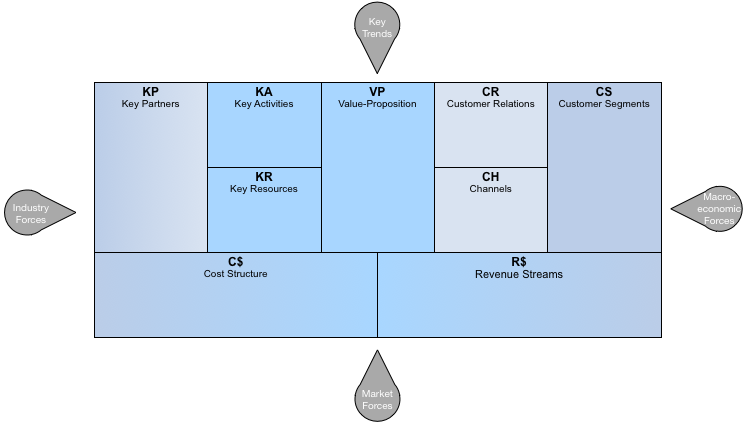

To make sense of this, we need to zoom-out. The Business Model Generation book does make a start on this, with what it calls the Environment Map:

The focus-areas in the Environment Map are ‘Key Trends’, ‘Industry Forces’, ‘Market Forces’ and ‘Macroeconomic Trends’. They’re all nice futures-type concerns: for our drug-pusher, that would include new designer-drugs coming down the pipeline, for example, or new manufacturing techniques, new distribution-channels opening up, that kind of stuff.

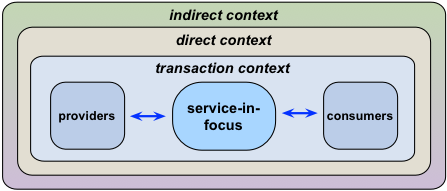

But yet it kinda misses the point – perhaps in particular, that the ‘environment’-context is not just about what might be happening in the future, but what is happening right here, right now. To illustrate this, let’s lift the colour-coding from another part of the Enterprise Canvas context-map, first in its generic more-abstract form as the basic business-model’s direct-context:

And in more specific form as the business-model’s market-context: the stakeholders in that broader market:

So as we zoom out from BMCanvas itself, we can see that the BMCanvas Environment Map is, in essence, just a subset of information about what is or could be happening within that market-context. Those themes are still here, but what probably concerns us much more is the impact on our business-model of those other stakeholders that now come into view:

Hence, for example, one group of regulator-stakeholders that our drug-pusher needs to worry about is the police. The cost of getting caught could well be jail – or worse, in some jurisdictions. That’s a real cost – yet it’s not a cost that we could meaningfully measure in monetary terms alone.

Another group of stakeholders out there in the market, for our drug-pusher, is ‘the competition’ – other drug-pushers, and more, all the way back up the drugs supply-chain. The cost of getting into a turf-war with some of those could well be that of getting shot. That’s a real cost – yet it’s not a cost that we could meaningfully measure in monetary terms alone.

In both cases, those are real costs, real factors that deeply affect the (literal) viability of our drug-pusher’s business-model – yet they’re not costs that we could meaningfully measure in monetary terms alone. On the bare BMCanvas, the drug-pusher’s business-model looks very profitable indeed: but perhaps not so profitable to those coming to the morgue today to collect yet another corpse…

There are ways round this, of course. In perhaps too many cases, our drug-pusher could buy off the police, the judges, even the local lawmakers, and convert those respective risks to a simple monetary cost on the balance-sheet. Turf-wars can sometimes be turned aside by diplomacy or deals, or perhaps a few strategic assassinations… – all of which might again be marked down as a monetary cost. In those terms, we can perhaps still somewhat-kludge the description of the business-model such as to make a monetary-only view still seem to somewhat make sense.

But there’s another whole layer to this, that may mean that even that kind of kludge won’t work. In Enterprise Canvas, this is the broader shared-enterprise or, in more abstract terms, the indirect-context for the respective service:

In market terms, this sits ‘above’ or ‘beyond’ the market itself:

And it includes a whole swathe of other stakeholders who share some kind of connection with the shared-enterprise-as-story – and about whom we might use the not-entirely-joking definition that “a stakeholder is anyone who can wield a sharp-pointed stake in our direction”:

The catch is that although the connection with them is usually only indirect, from a business-model-perspective, they can still cause the business-model to fail – and fail in ‘unexpected’ and ‘inexplicable’ ways, if we’re not aware of those stakeholders and their potential impacts on that business-model. But if we are aware of them, and work with them, they can also help our business-model to thrive, in ways that we and others may not expect at all.

Those stakeholders will certainly include any ‘outside’ investors and beneficiaries – who, again, are likely to invest and to take returns in many different forms, often much broader than money alone.

Those stakeholders would include government in the broader sense.

Those stakeholders would include families of employees and the like.

They include the communities in which the organisation operates, or in which the families of employees and others might live.

They include people who connect only as a ‘citizen‘, rather than an actual or potential customer or supplier.

They might include people who connect with this shared-enterprise only through someone else’s co-branding.

They might include non-clients – people who have been clients in the past but now aren’t, or who could be in the same nominal market but unable to engage, in a different country or whatever.

They might well include anti-clients – people who are committed to the same shared-enterprise, but who strongly disagree with the way that the organisation operates within it.

And the connection here is always about value and values – only peripherally, if at all, about mere money, in fact in many cases bringing money into the picture only makes things worse. Our drug-pusher might be able to buy off the police, the judges, the entire ‘leadership’ of local-government – but at some point, something’s gonna snap out there in the broader shared-enterprise, and our drug-pushers will suddenly find themselves coming face-to-face with their own equivalent of the events described in the post ‘When leadership takes risk‘.

A business-model always involves more than mere money: when designing a business-model, we forget that fact at our peril…

And when we take it right out to that broader scope, we can summarise all of this visually as follows:

So whilst mapping out a business-model might at first seem to look as simple as this:

Yet in practice, and in reality, the mapping not only might but will need to both zoom-in and zoom-out quite a long way, to something that looks more like this – the real scope of a business-model:

In short, we must remember that whilst simplicity is useful, reality is rarely as simple as that simplicity portrays. And always, always, always remember that a business-model involves much more than money alone – and that we need to track the full flow of values and value throughout the entirety of that business-model.

Hoi Tom

Good points. The value proposition is not the product, it is the proposal of the firm which overall value the company creates for its customers but also to its most important partners and stakeholders. The value proposition is just a proposal which has to be fulfilled by all other building blocks as well and not just by the offering.

The revenue model is the way how the company captures the value it creates in money terms. However, we are humans and therefore we do not only work for money but also for meaning. And the value proposition has to give meaning not only to the customers but also to the employees. Therefore, we need the human side in business models as well. Therefore, I have introduced a team & value element in the business model. The human values are core to the delivery of any value to customers and also for any change. We can only innovate the business model when we integrated the values and corporate culture into the innovation process. Take a look here http://blog.business-model-innovation.com/2009/10/culture-and-the-business-model-we-are-humans/ or at the full canvas http://blog.business-model-innovation.com/tools/ with all the elements that create and captures value.

Cheers Patrick

Thanks for this, Patrick – and yes, very strong agree about “we need the human side in business models as well”.

As you can see in the post above, I do take the scope of stakeholders further out than you perhaps would, but the general principle that it extends far beyond the organisation itself applies for both of us.

I would love to talk with you further on this: meet up somewhen soon, perhaps? Thanks again, anyway.

Tom,

I’m writing a kind of response to your post on my blog, since the topic of value creation and capture is important and I think you are right with your points. However, I do believe that we should not expand the scope of the business model too much. By saying so, I am totally aware that a business is deeply entrenched in society, in competition and technological innovations. But the business model should just describe a business so we can see the configuration how the business creates values. I introduced the business model as a unit of analysis in my Ph.D. in 2001, since we had no unit of analysis to understand how digital media are changing the businesses. And I was very much surprised that there was no definition what a business is. And therefore I introduced the business model as a unit of analysis of strategy. Most of the building blocks you see by Alex are already introduced by me some three years earlier.

It is important to notice the limitations we set deliberately. The business model as it is known today is for strategy making and not for enterprise architecture to build the IT systems to support the business.

The original concept of the business model came from the IT architects with their thinking in data models and enterprise models but moved during the first New Economy to the level of strategy. Therefore it was important to me to focus only on the relevant parts for strategizing. For competitor or stakeholder analysis we have enough tools but we had no tool to understand how a business really works.

Cheers Patrick

P.S. Would be lovely to meet. I’m based in Zurich and currently I do not have any plans for the UK.

Thanks again for your comments, and yes, agree with what you’ve said on your blog.

To me there are two different concerns going on here, and I fear we’re managing to confuse each other about how they interact! 🙂

One is the business-model as model of the basic transactions and interactions. The audience for that is people working in ‘the business’, usually at fairly high-level, where the whole point is simplicity for attention/time-starved people. And the scope is quite narrow: often no more than Alex’s somewhat over-simplified notion of ‘how the business makes money’. To me, that’s where Alex’s work most clearly applies – it’s easy to digest, and flick through alternate options. It’s great at getting people started, but the danger is that – as per the post above – it kinda glosses over a lot of very real problems and risks that can kill a business-model in ‘unexpected’ ways.

The other is the business-model as an overview or central-theme within a much larger picture – closer to Alex’s initial definition of ‘how an organisation creates, delivers and captures value’. The audience for that is the poor saps who have to make sure that the grandiose schemes of a BMCanvas can actually work in real-world practice – people such as enterprise-architects, channel-designers, business-analysts, process-designers and all that. These people often need to reach out to a much wider/deeper scope – a full ‘zoom-in’ and ‘zoom-out’, to use Alex’s terms – all the way out to anticlients and kurtosis-risks, and all the way down to fine implementation-detail, though always guided by the key principle of ‘Just Enough Detail’. That’s where most of my work applies: it’s about taking those often over-simplistic models and making sure that they can actually work without getting impaled on some hidden ‘gotcha’ at some unexpected point of scope and detail.

To me your work sits somewhere between those two: arguably more ‘real’ than Alex’s, but (given your business-oriented audience) also wisely avoiding any hint of risk of ‘analysis-paralysis’. Would that be about right?

(An important point, by the way: to me enterprise-architecture is not solely about IT – as too much of ‘EA’ currently still is – but about the literal ‘the architecture of the enterprise’ as a whole, looking outside-in as much as inside-out. In other words, whilst ‘classic’ ‘EA’ has a much narrower scope than business-architecture, the EA I work with has a much larger scope – a very important difference.)

You say: “Therefore it was important to me to focus only on the relevant parts for strategizing. For competitor or stakeholder analysis we have enough tools but we had no tool to understand how a business really works.”

Yes, agreed: there were plenty of tools for the deep-detail levels, but not enough for the ‘business-model’ level. What I’m illustrating here is that there’s another whole gap ‘above’ even the business-model – the broader context within which the business and business-model would operate. What I’ve been working on – and published in the book ‘Mapping The Enterprise’ and the many blog-posts here on Enterprise Canvas – is a means to link all the way from really-big-picture to really-small-detail and back again, and also all the way from strategy to tactics to operations and back again.

The hardest challenge – and this comes back to your point about “I do believe that we should not expand the scope of the business model too much” – is to manage the ‘Just Enough Detail’ constraint. It’s the classic Goldilocks balance: not too little, not too much, but just right. Yet we need to be clear at all times that the scope is always the whole enterprise, all the way out to really-big-picture, and all the way down to the smallest-detail: every time we constrain our view of that scope, we need to know that we’re arbitrarily constraining it, know why we’re constraining it, and know what the risks and implications are of so constraining it. If we don’t do that, we would inherently and by definition be placing our assessment of the business-model at risk – and the business with it.

Seems to me that there’s a real opportunity here if we can find a way to incorporate into business-model work this ability to go into the big-picture/small-picture at need, but without frightening anyone about the sheer scale of it. (The whole of the scale of the enterprise does need to be addressed by someone, eventually, but it doesn’t all have to be done at once by one team! 🙂 ) One way to do that would be to build a clean bridge between your business-model work, and my work on whole-of-enterprise architecture with Enterprise Canvas and the like. A suitable topic for a meetup, perhaps?

I’ll write separately about options for a meetup in Zurich – and thanks again, anyway.

Good work Tom. I find value proposition is a function of understanding the business model of the other – employee, customer, shareholder etc.

I’m often in negotiations where we are modelling up the other’sbusiness model to understand our relationship to their success/goals. It’s surprising how often this process changes the perception of value on both sides of the table

Thanks, Peter – and yes, good point about “It’s surprising how often this process changes the perception of value on both sides of the table” – that’s been my experience too.

(Would like to talk more with you about your work on this – perhaps when I get back to Australia again, which I’m aiming to do later in the year?)