Enterprise-architecture – a further-futures report

We’ve explored the current status for enterprise-architecture [EA]; we’ve explored the changes to the discipline over the past few decades. Time now, perhaps, to assess the future – or futures, rather – of its likely onward development and direction.

This report is in two parts:

- 1: Near-future – 1-10 years

- 2: Further-future: 10-50 years (this post)

First, though, a quick summary of key principles on the focus and role of enterprise-architecture:

- core theme is that things work better when they work together, on purpose

- we develop an architecture for an organisation, but about the shared-enterprise(s) of that organisation’s context

- architecture-work may apply to any scope, any scale, any content, any context

- we provide a balance and bridge between structure and story

As a discipline, EA is a generic toolkit for integration, connection, relations, across an entire context, with fully-fractal assumptions, definitions, tools, frameworks and methods, drawing on key skills such as complex problem solving, critical thinking and creativity.

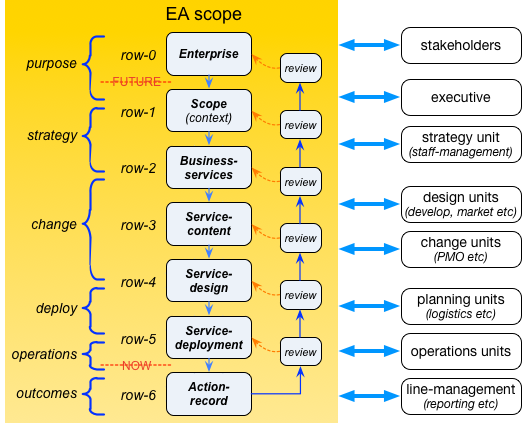

What EA brings to the party is that emphasis on connection – on getting things to work better, together, and ‘on purpose’. As such, it’s probably the only discipline that can or will bridge everywhere across an entire enterprise, across all stakeholders at every level, from strategy to execution and back again:

Crucially, the architect’s role is about decision-support, not decision-making. The architect brings clarity on what the choices are, and why – yet the final choice always resides with the client, not the architect. The further we expand the scope and scale of architecture, the more important those points become…

And architecture is fractal. Over the past few decades we’ve learnt how to do architectures not just at project-scale and department-scale, but whole-organisation scale as well. And in the previous part of this report, we explored some of the types of work that is already being done in ‘big-picture enterprise-architecture’, not just beyond IT, but beyond the boundaries of an organisation too, finding better ways to balance ‘inside-out’ and ‘outside-in’.

Yet if architecture is fractal, then there’s no reason why we should stop at that scope and scale. And there are plenty of urgent reasons now why we can – and should – continue onward from there. So this part of the ‘EA-futures report’ is likewise a direct logical progression from the same methods and suchlike, but at an even broader scope and scale – in other words, ‘really-big-picture enterprise-architecture‘ [RBPEA].

(I’d guess that a fair few people may find this post not so much controversial as laughable. Yet before you laugh too loud, remember my track-record here? – a decade ago, most people in ‘the trade’ still mocked me for suggesting that EA should be about more than just IT-infrastructure…)

Okay, right now there are perhaps only a handful of people worldwide who are working out there in the RBPEA space. But to me it is the future of EA, and it is already happening. Or at the very least, some of the fault-lines that will drive whole-of-society-scale change over the next half-century or so are already out in the open, ‘hidden in plain sight’, and the architectural approaches with which we’d need to address them are becoming more clear as well.

For example, consider sustainability. Although the concept has many different connotations, one key international definition is that:

[sustainability is] meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs

The blunt reality is that, in global terms, we’re not doing well on that one…

More worryingly, we’re not even doing well on how to train and organise the new kinds of work that we’d need in order to do well on that one. For example, to quote from a World Economic Forum study:

our educational system is not adequately preparing us for work of the future

At a societal scale, we don’t even know how to support the people doing that kind of work:

just because a profession is producing something desirable, or even necessary to the functioning of society, doesn’t mean society has figured out a way to pay for the care and feeding of its practitioners

And, to make it even worse:

our political and economic institutions are poorly equipped to handle these hard choices

On the surface, there’s perhaps not much we can do about these themes right now – to be blunt, most of our ‘world’ isn’t ready for that as yet. But even now, we can at least look, and then think carefully about the architectural implications at that same very large scale – so that when the time comes, we are ready to take appropriate action, and fast.

In the nearer future – up to around 20 years from now – probably the main focus will need to be around the skills-challenges, as above, and also doing much more towards implementing a circular-economy model, in manufacturing and preferably more. None of this is actually new: many traditional cultures have been doing this as deliberate practice for millennia, and even in the industrial context there are well-established exemplars such Ray Anderson’s ‘Mission Zero’ at Interface Inc. Ideas such as sustainable-design, eco-design and Nicholas Nassim Taleb’s antifragility could also play a key part in providing principles to guide whole-enterprise architectures in this broader space.

But beyond the 20-year mark – or, increasingly, for RBPEA work anywhere from 10 to 50 years from now? – well, that’s where things are going to get messy…

Back about twenty years ago I coined the concept of a mythquake – the societal equivalent of an earthquake, in which the tectonic plates of the soul and the broader society come into collision with Reality Department. Perhaps the simplest way to describe the core drivers behind this is Richard Feynman’s blunt warning, in the last sentence of his addendum to the Rogers Report on the Challenger disaster:

For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.

In short, a mythquake occurs whenever there’s a mismatch between expectation and reality – and reality always wins in the end. The severity of a mythquake rises steeply with the level of self-delusion – hence, for example, as Feynman also warns in his Rogers Commission addendum:

When playing Russian roulette the fact that the first shot got off safely is little comfort for the next.

In my work on mythquakes, I mapped out a basic severity-scale, from MQ-1 to MQ9, roughly paralleling the physical-world Richter and Mercalli scales for earthquake energy and impact respectively. An MQ-1 mythquake is something we’re all likely to experience many times a day – trivial in real-world terms, though it may not feel like it at the time! – whilst an MQ-3 is the level we and those around us might feel at the loss of identity on losing or moving on from a previous job. An MQ-5 mythquake is what we’d expect to see now with any major financial-crash, such as that in 2008 – large-scale impacts, all the way up to global scale.

Mythquakes at MQ-6 and upward are fortunately rare, but their impacts are correspondingly huge – which is perhaps most people avoid talking about them at all. When I wrote about RBPEA implications of the MQ-7 level societal messes around gender, what I got back was mostly a thunderous silence, with a few accusations of ‘misogyny’ and suchlike thrown into the mix – which completely missed the point, of course. And much the same – though perhaps with an even more thunderous-silence – when I wrote about MQ-8 level delusions about ‘rights’ and the like, and on to the MQ-9 level disasters-waiting-to-happen lurking beneath the many myths and sensemaking-sins about possession. The blunt reality, though, is that when faced with major mythquakes, wilful-ignorance is not a survival-strategy – yet that’s about all that most people seem to be doing about this right now…

Which is why, to me at least, this is a genuine and urgent role for enterprise-architects – because we’re one of the very few disciplines that has appropriate skillsets right now to apply to these lethally-real concerns.

(That they are indeed urgent concerns now should not be in doubt. For example, our current economics not only assumes but requires the existence of infinite-growth – yet even the most basic logic indicates that we cannot have infinite-growth on a finite-planet. It’s already been more than forty years since the ‘The Limits to Growth‘ study showed that even back then we were already hitting up against non-negotiable barriers and constraints at a global scale – and we’ve gone a long way further down the path towards non-survivability since then. Oops…)

So, first, some practical realities:

- the money-system can ‘grow’ to infinity, but the real-world can’t – so we cannot have an infinite money-system that assigns itself ‘rights’ to definitely finite resources

- the money-system itself introduces many lethally-destructive distortions – so we have to find a way to run an economy without money or any other form of ‘metacurrency’

- the concept of ‘rights’ is a literally-lethal dead-end – so we have to find a way to restructure the entirety of our social and economic systems beyond any concept of ‘rights’

- every item or resource we dig up and throw away is something that, in effect, we’re stealing from the future – so any form of planned-obsolescence needs to be understood as a crime against the future

- much of our justice-systems depend on possession-based threats such as confiscation and monetary ‘fines’ – so we need to redesign our justice-systems in ways that do not depend on any form of possessionism

And yes, that’s definitely non-trivial…

Yet in reality most of the underlying principles for what to do about all of this are very simple indeed. For example:

- Bob Marshall‘s ‘antimatter-principle‘, of “attend to folks’ needs”

- reframe all law in terms of ‘principle-first’, not ‘rule-first’

- reframe power as ‘the ability to do work’, not ‘the ability to avoid work’…

- the only relationship that works is from responsibilities, not ‘rights’

- the only outcome that works is ‘win-win’ – everything else is an illusory form of ‘lose-lose’

- everything is interconnected – systems within systems within systems intersecting with other systems

The moment we move away from any of those principles, we create unneeded complexity, unnecessary fragility and, all too often, serious social-dysfunctions; but when we move towards those principles, we inherently reduce complexity, fragility and dysfunctionality. For example, consider what happens when we dump the delusion that the money-economy can ever be made to work:

- we break free from the parasitism that underpins the stock-exchange and suchlike

- we no longer describe a new development as ‘an opportunity to make money’, but as an opportunity for soul-engagement

- we can refocus attention on ‘low-profit’ but highly-important themes such as infrastructure

- we can end the fragmentation caused by privatisation of shared-resources such as tollways and the like

- we can provide support for all of societal needs – such as parenting and elder-care and and artistry and futures-work – rather than forcing all attention onto that lesser subset of skills and activities that ‘make money’ for someone else

In short, applying the principles properly means that we can break our organisations and economies free from the petty parasitism that underpins the present-day fetid swamp of top-down Taylorist disservices:

And turn them round into genuine services, each interdependent with each other, based on viable values–architectures, and in which management is merely ‘just another service‘, no different and no more important than anything else:

And yes, there are many other themes we might consider, even right now, such as:

- we need to refocus education to developing meta-skills and systems, and emphasise life-long learning

- we need to refocus technology in areas where it works best, in predictable or ‘order’-type contexts, and provide better support for humans doing ‘unorder’-type work

- we need to ensure that AI and similar technologies always remain human-comprehensible – not least because the reality of high-order kurtosis-risks such as a Carrington Event means that we need catastrophes to be survivable without the availability of advanced technologies

To illustrate this, and just as a thought-experiment, go down to your local town-centre or shopping-mall, take a look around, and then ask yourself questions such as these:

— What would a shopping-centre be like – be for – if its focus was not about pushing junk that no-one needs, but instead about supporting what people do need?

— What would be the purpose – if any – of banks, insurance, real-estate and many more, if the economy did not depend on money, and hence no need for money?

— What would happen to food-shops if the focus was no longer on pushing junk-food at ‘low prices’, but instead truly concerned about people’s health?

— What would clothes-shops be like if the focus shifted from creating artificial ‘wants’ for poor-quality overpriced tat, to clothing for life – a focus on wearability rather than disposability?

That’s what we’re really looking at here, as the real role for enterprise-architecture in the further-future.

To be blunt, what we live in right now is not so much an oligarchy, or a patriarchy, or even a kleptocracy, but a paediarchy – ‘rule by, for and on behalf of the childish’. In essence, our entire economics is built around the possessive temper-tantrum of a two-year-old – the incessant shrill cries of ‘Mine! All mine!’ and ‘Want it now!’. Kinda dispiriting, really. And the huge danger – the very real danger – that all of face right now is that that paediarchy is inherently incompatible with our long-term survival. Oops…

Yet as enterprise-architects, how do we create the support and structures needed for a shift from the present-day possession-based model, to a more viable responsibility-based model, when there are so many vested-interests in maintaining the dysfunctional systems and structures? Creating the conditions for that change is the professional challenge that we face right now – and for the next fifty years or more.

No doubt we’d love to keep all of those complexities out of our own EA-story, and to be able to wave around a sign like this:

But the blunt reality is that, whether we like it or not, enterprise-architecture will always be ‘relentlessly political‘. We need to face up to that fact – and face up to our responsibilities to take action now, towards a more survivable future.

I’ll leave it at that for now: over to you for comments, perhaps?

Brilliant!

Add in that a entarch must be fearless in its efforts to architect for the future now.

From an EA and sustainability perspective Christian Brockmann’s figure 1 (institutional layers surrounding the construction industry) in his 2001 paper “Transaction costs in relational contracting” (AACE International Transactions; 2001; pg. PM.06.1) makes interesting reading.

In his paper Brockmann “… transfers ideas from (institutional) economics to the field of the construction industry. It analyses the relationship between client and contractor and searches for new ways of working together for a mutual benefit.” As EAs we work in an institutional context, so it helps to have some understanding of the extensive and growing theory of institutions.

Many thanks all, for all of those good points – it really does help us in clarifying what it is that we actually do… 🙂

Tom, politics is how things get done at scale. It’s not something to be avoided, it’s to be harnessed. We make decisions with emotions, and sometimes with a veneer of post-hoc logic rationalisation. Shopping centres are not just about consumerism, they are social centres. Banks are not just about money, they’re about reassurance. Food is for comfort, not just nutrition. Clothes shops are about fashion, which is pure emotion, not about covering up. Marketers and advertisers have always understood this. If your point is that EAs need to catch up, I agree, but they’re not uniquely equipped to do that.

Thanks, Andrew.

Re “politics is how things get done at scale. It’s not something to be avoided”, short answer is “yes, of course, no question”. (I presume you did notice the line in the penultimate para of the article above, that “whether we like it or not, enterprise-architecture will always be ‘relentlessly political‘”?) The question we do need to consider is what’s meant by the term ‘politics’. In my understanding, there are two levels that matter – the immediate human, the scale of the village, and the very large scale, measured in decades and centuries – and the interweavings between those two scales. The one level that doesn’t matter, and is for the most part a disastrous menace, is what most people understand as ‘politics’, namely the childishnesses of party-politics and the like, the endless petty wranglings over the position of deckchairs – or these days, one single chair – on the deck of the Titanic. Most of what passes for ‘politics’ these days is mere rabid paediarchy and possessionism, the self-obsessed squabblings of overgrown two-year-olds – it’s the near-exact antithesis of the meaning of ‘politic‘. Important not to confuse these, or think they’re the same thing…

Re “Shopping centres are not just about consumerism, they are social centres” – they were, yes. These days they are explicitly ‘private property’, where anything other than consumerism is almost literally a crime.

Re “Banks are not just about money, they’re about reassurance” – disagree: these days they’re at best about manufacturing a known-empty delusion of reassurance. If you want to see a solid myth of reassurance, take a long careful look at how banks used to present themselves a century and more ago, before they became, again, mere transactional elements within a cult of consumerism. To be blunt, the entire mess of ‘finance’ behind that that façade is a machine for automated theft – or, at the very least – life-theft – on a truly gargantuan scale.

Re “Food is for comfort, not just nutrition” – in principle, yes. The two now seem to be divorced, almost to the point of absurdity: ‘comfort-food’ aplenty, almost all of which is, again, the near-antithesis of ‘nutrition’. (My parents were GPs: it’s been bleakly interesting to watch how malnutrition has changed over the past sixty years or so, from post-war near-starvation to the present-day’s bizarre mix of endemic anorexia and rampant obesity, often in the same person. The Second World War changed everything for everyday people, by the way: rationing meant that everyone had just-about enough to eat, which for many working-class people meant the first viable diet in their lives. We seem to have reverted back to much the same disaster of malnutrition as in the pre-war period, but from an excess rather than a shortage of increasingly-deadly ‘cheap food’. Odd…)

Re “Clothes shops are about fashion, which is pure emotion, not about covering up” – of course: but why on earth does this need saying? Are you somehow assuming that because I’m asking architects to think, I’m therefore saying that we should not feel, that we should shun feeling entirely? Let’s just say that I’m not that binary… – and nor should any architect be, in my opinion.

Re “Marketers and advertisers have always understood this” – yes. Usually, however, with an acute absence of anything resembling ethics, or awareness of the big-pictures consequences of what they’re ‘selling’. That’s a kinda important difference, perhaps?

Re “If your point is that EAs need to catch up, I agree” – good: we do agree on something.

Re “…but they’re not uniquely equipped to do that” – depends what you mean by “that”, of course. What architects do uniquely bring to the table is the emphasis on how things work together, on purpose – and in the space between the boxes as much as within them, too.

Which is the whole point of what I’ve been writing about, here, for the past ten years. With tools to work in those spaces. And detailed explanations of how to use those tools to work in those spaces. And so on… Yes, there’s a lot of it: some 1200 articles here, plus the dozen or so books, plus all the slidedecks and so on. Yes, there’s so much of it that’s kinda hard to navigate one’s way around it – and yeah, I know that, and I do know that making my stuff more accessible is something I urgently need to address. Yet you’d appreciate that it’s kinda hard to do that with almost no income, almost no support, almost no resources and almost no time, and ever-increasing pressures to do more and more with less and less – not least from the blunt fact of my own fast-approaching mortality?

Hence, rather than merely telling me I’m wrong and then wandering off again, a bit of concrete help here could be kind of useful, you know? For everyone involved – including you? Your choice, of course.

Oh well.

Tom, I appreciate the detailed response, and I totally respect your aspirations and efforts to build tools to improve the way enterprises are run, and the world they interact with. I’ve been reading your blog for a few years, and I get it. My point was that the messiness of the world, including low-level politics, and even marketing, is a given. It’s how people work, and how we work together. It’s neither good nor bad, it just is.

On where you should focus your energies next, my $2 opinion, FWIW, is that your message can get lost in the volume of words. I’d be finding myself a sub-editor, maybe even a social marketer, distil and sharpen up the core messages with a fresh approach for a new audience, and get them back out there with a catchy tool/app/sketchbook/whatever. I don’t know your style, but hey, it worked for Jurgen Appelo…

Thanks, for the reply, Andrew.

Re: “My point was that the messiness of the world, including low-level politics, and even marketing, is a given. It’s how people work, and how we work together. It’s neither good nor bad, it just is.”

Yes, I know this. I said it explicitly in the post above, and I repeated it again in my reply to you. I don’t understand why you continue to assume that I don’t?

Re: “your message can get lost in the volume of words” and “I’d be finding myself a sub-editor”.

Yes, I know. Others complain about this, too. There are three practical realities about this:

— One is that it takes much, much longer – a full order of magnitude longer – to edit something down to the pithy sentences that marketers love: and I simply don’t have that kind of time.

— Next is that it’s very easy to over-simplify this to the level of destructive-uselessness (e.g. Gartner’s beloved ‘Bimodal-IT’), or to ramble on yet leave gaping holes (e.g. TOGAF/Archimate): getting the balance even some way towards right is very, very hard and very time-consuming work.

— The other is that if I leave anything out at all, or fail to cover even the most petty minutiae, I either get dismissed out of hand, or attacked, instantly – and the amount of time and effort that it takes to address those attacks is, again, another order of magnitude greater than writing out the explanation beforehand.

In short, to make something seem simple, ‘obvious’, usable and valid in real-world use is all incredibly hard work. If you’re not willing to do that level of work yourself, please don’t be quite so quick to denigrate those who do?

Re “maybe even a social marketer … it worked for Jurgen Appelo” etc.

Yes, I know. I plead the blunt reality that ten years very hard work on almost zero income (way below minimum-wage, for all of that time, whilst watching a fair few others make fortunes out of that work) – well, it does kinda constrain one’s options, you know? And at so-called ‘retirement-age’, my ability to stomach the sheer vapidity and venality of the commercial world is all but gone: I’d rather do something useful with what little remains of my life. 🙁

Re “sharpen up the core messages with a fresh approach for a new audience, and get them back out there with a catchy tool/app/sketchbook/whatever”

Yes, I know. I’m working on it, as hard as I can – when not distracted by replying to queries such as this, that is…

Apologies if I sound testy: to be honest, I am – though more at the whole darn world, rather than you in particular. As per the post ‘More on not-retiring’, that came after this one – see http://weblog.tetradian.com/2016/09/22/more-on-not-retiring/ – I’m facing the fact that even if I do nothing new at all, and have no time for any kind of paid-work, I still have at least 10-20 years’-worth of work to do just to tidy up what I already have, yet probably no more than 10 years left in which to do it. There are times when the implications of one’s mortality are not exactly easy to face, and for me this is one of them. Expect big changes soon, as priorities necessarily get rearranged.

Thanks for your reply. I agree with you, it is all in the eye (and ear) of the beholder. My apologies for the long comment but I feel the need to fully explain my view. The hackneyed phrase “a picture paints a thousand words” hides a plethora of problems:

1) Most pictures are in 2d & the artist has to rely on shadows & perspective. Art such a graffiti tries to use words but the message gets garbled due to limited space, poor spelling & lack of understanding on the part of the artist and the viewer etc.

2) A word has synonyms & hypernyms hence the use of a word can get misinterpreted – ergo the cryptic crossword puzzle & double entendres

3) The spoken word relies on language, phonetics (eg so & sew), dialects, accents etc & hence can convey the wrong meaning

4) Acronyms which too can be very confusing

5) Sentences need to paint a picture using words, & grammar (punctuation & major form classes such as nouns, verbs etc.)

No wonder the message often gets misunderstood.

In my mind, RBP in both enterprise and information architecture paints the image of a 4d ‘hiernet’ (a structure that is both 3d, made up of hierarchies & networks & spans time. This has & will never change. The secret to unravelling this picture is to have some form of ‘catalyst’ or ‘lens’ (perhaps a TARDIS) which never changes during the journey through the structure. In 1989 I set out to create such a ‘catalyst’ based on my nearly 2 decades of exposure to techniques that were available to me at the time (program language syntax, programming specifications, systems analysis, Codd’s normalisation technique, JSD technique, SDLC, MBA, MBO, IE, SWOT, OO & UML). The result was a really big, fully integrated structure that in order for me to develop an AI vehicle had to use the general ideas of:

~ OO – encapsulation, inheritance & polymorphism, which imho has its roots in the structure of the COBOL language which I learnt to program in 1970

~ The SDLC – by ignoring the use of data flows to try to specify processes & discover the data stores

~ Codd’s work – by realising a structure in 3nf did not portray the real world but an extraction of it

~ IE – by noticing the redundant process of information analysis & data analysis (both having their roots in Codd)

~ SWOT – by ignoring its strategic planning approach as it needed objectives

~ UML – by ignoring it was imho was just a rework of data flows

~ MBO – by studying the structure of objectives

~ MBA – after studying Peter Drucker’s course material & discovering the redundancies in the material

~ Program language syntax – by ignoring the likes of COBOL, Pascal, Basic and using a far more advanced IDE that ran on both Apple & PC

I have therefore looked at the RBP & developed both the Technique & compiler to be able to ‘frame’ it.

Nice Information.

I posted a response a while back on the LinkedIn version of this post at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/enterprise-architecture-further-futures-report-tom-graves.

That note suggests that EA needs to be understood as “systems architecture” — we need to abstract away from “enterprise” and move toward an understanding that it (architecture) is a general system discipline.

My addition, is that we need to evolve to a point of understanding that “architecting” is something we all engage in, and have responsibility for. This is in partial contrast to the viewpoint of paediarchy – ‘rule by, for and on behalf of the childish.’ I think it implies a conscious desire to use that as a architectural steering principle. I don’t think that is correct. I think the reality is that we are running on overload and drifting into anarchy relative to our ability to manage the systems we have created. And the result is unregulated systems at global scale.

There are folks for whom this is advantageous. And treating others like children works for them. But there is also a counter movement.

The solution, I think, is to try to restore democracy and put the people back in change of their systems. They need to understand architecture, and how their actions affect it. That can’t wait 10 to 50 years. It has to start happening sooner. The current unrest indicates it is already in process.

Thanks Joe (and apologies for the tardy reply…)

— “EA needs to be understood as “systems architecture” — we need to abstract away from “enterprise” and move toward an understanding that it (architecture) is a general system discipline” – yep. That’s whole point behind my work on enterprise (i.e. beyond the self-centric ‘the organisation is the enterprise’) and on RBPEA, Really-Big-Picture Enterprise-Architecture.

— “we need to evolve to a point of understanding that “architecting” is something we all engage in, and have responsibility for” – you’ll find no disagreement with me on that. 🙂 That’s exactly the kind of approach I’ve been pushing for a very long time: see, for example, the post ‘Four principles – 2: There are no rights‘.

— “This is in partial contrast to the viewpoint of paediarchy” – not really. The most useful distinction, perhaps, is between non-competence and incompetence (see ‘Competence, non-competence and incompetence‘): when competent people hit overload, they typically move into non-competence, whereas paediarchy is driven by delusions of competence, in other words incompetence all the way through.

— “That can’t wait 10 to 50 years. It has to start happening sooner” – strong agree on that.

— “The current unrest indicates it is already in process” – sort-of. The way I read it is that there’s a sort-of acknowledgement that it has to happen, but it’s still a bit blurry for the majority of the general public (whose ‘education’ has historically been designed/structured to prevent awareness of systems-as-systems). In the meantime, the dominant paediarchy is making a massive pushback to protect its purported ‘rights’ to act as a paediarchy. The clash arises from a reality that pushes us towards a systems/responsibility-type model – otherwise, bluntly, we’re dead, quite possibly as a species – whereas paediarchy desperately wants to hold on to delusions of ‘control’ that do not and cannot work any more. (The one-line summary is that a possession-based economy can only run as a pyramid-game: what we’re seeing right is what happens when a pyramid-game runs up against non-negotiable limits to the size of the ‘game’ – otherwise known as ‘you can’t have infinite ‘growth’ on a finite planet’…)

Hope that makes some degree of sense?