Services and disservices – 5C: Social example (Media-examples 6-9)

Services serve the needs of someone.

Disservices purport to serve the needs of someone, but don’t – they either don’t work at all, or they serve someone else’s needs. Or desires. Or something of that kind, anyway.

And therein lie a huge range of problems for enterprise-architects and many, many others…

This is the fifth part of what should be a six-part series on services and disservices, and what to do about the latter to (we hope) make them more into the former. This part ended up being far larger than expected (some 12,000 words), so it’s been split into four sections, of which this is the third:

- Part 1: Introduction (overview of the nature of services and disservices)

- Part 2: Education example (on failures in education-systems, as reported in recent media-articles)

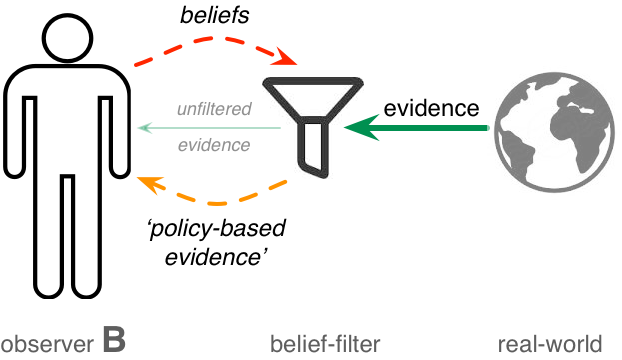

- Part 3: The echo-chamber (on the ‘policy-based evidence‘ loop – a key driver for failure)

- Part 4: Priority and privilege (on the impact of paediarchy and other ‘entitlement’-delusions)

- Part 5: Social example (on failures in social-policy, as reported in recent media-articles)

- Part 5A: Social-example – Introduction

- Part 5B: Social-example – Media-examples 1-5

- Part 5C: Social-example – Media-examples 6-9 (this post)

- Part 5D: Social-example – Implications for EA

- Part 6: Assessment and action (on how to identify and assess disservices, and actions to remedy the fails)

In previous parts of this series we explored the structure and stakeholders of services, and how disservices are, in essence, just services that don’t deliver what they purport to do. We then illustrated those principles with some real-world examples in the education-system context. Following that, we outlined some of the key causes for disservices – in particular, the ‘echo-chamber’ of misplaced, unexamined belief, and ‘power-against’, a dysfunctional misconception of power as ‘the ability to avoid work’ – and derived a set of diagnostics to test for these.

In this post – Part 5 of the series – we’ve started to put all of that into practice, in assessment of real-world services. To complement that previous exploration of education-services, we’ll look at social-services, and the social-policy that underlies them. For reasons explained in the previous section of this post, the example of services from social-policy that we’re exploring here is around identification and resolution of domestic-violence.

The catch there, of course, is that, as with education, these domains are highly ‘political’, so I’d better reinstate the same warning-sign from the earlier post:

I’ve suggested a probable vision/purpose for the DV-resolution enterprise that we can use as a touchstone throughout this assessment:

- that all parties feel safe and comfortable expressing themselves and doing things

And to counter the risk of any potential ‘Misuse, abuse and violence’ arising from the assessment itself, we could perhaps keep reminding ourselves that:

- there is never an excuse for abuse or violence, from anyone, to anyone, including Self

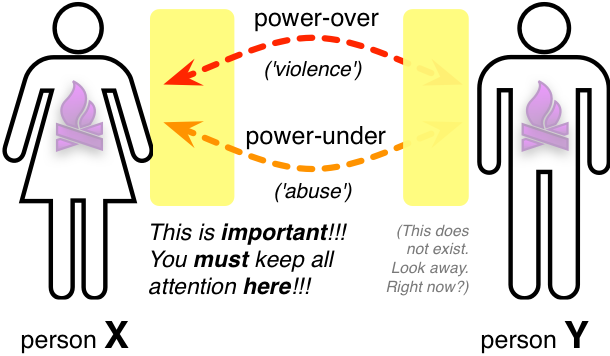

Our starting-point in the Introduction to this post was that the Duluth Model – the supposed ‘standard model’ for the DV context – posits an asymmetric Starhawk-type power-model operating within the DV context, which asserts that males are the only perpetrators of abuse, and females the only victims. By contrast, if the power-relationships are not gendered as such, we’d expect to see evidence of a more symmetric model of power-dysfunctions – such as a ‘race to the bottom’ codependent ‘mess’.

What we’re concerned about here is whether a Duluth-style asymmetric model is being imposed, via an echo-chamber ‘policy-based evidence’ loop, on what is actually a more symmetric context for DV. If so, we would expect to see hints, and more, of a ‘priority and privilege’ structure that looks somewhat like this:

The reason for the concern is that if that is the case, then such distortions could create disservices on a truly vast scale, potentially damaging or destroying literally millions of lives. Otherwise known as Not A Good Idea…

So as with the education-example from Part 2, we’ve been exploring some recent media-examples in the DV context, applying the diagnostics from Part 3 and Part 4 to each, together with some thought-experiments to test out your own responses and understandings – and then inviting you decide what’s actually going on, and what could be done about it.

In the assessments below we’ll refer often to the abuse/violence categories list from Part 4, so it’d probably be useful to re-include the list here:

- A: Coercion and threats → Negotiation and fairness

- B: Intimidation → Non-threatening behaviour

- C: Economic abuse → Economic partnership

- D: Emotional abuse → Respect

- E: Misusing sexuality → Sexual respect and trust

- F: Priority and privilege → Shared responsibility

- G: Isolation → Trust and support

- H: Misusing children → Responsible (about) parenting

- J: Misusing others (third-party abuse) → Social self-responsibility

- K: Minimising, denying and blaming → Honesty and accountability

- L: Lying and dissembling → Truthfulness and transparency

Enough introduction, I hope? Let’s continue from where we left off, after media-example #5.

Media examples (continued)

(Important note: In this assessment, we must, of necessity, explore counter-examples to the current ‘standard narrative’ as promoted by the Duluth Model and its ilk. It’s essential to make it clear, though, that none of what follows should be taken as belittling or denying abused-women’s pain. All it may imply is that there may be a larger picture here, parts of which may be being blocked out by a ‘policy-based evidence’ loop, leading to damaging disservices to some or all stakeholders.

Remember that we’re not dealing with a zero-sum context here: sadly, there does not seem to be any limit to the supply of human suffering… In that sense, the existence of one person’s pain does not diminish or deny the existence of another’s: please keep that in mind when working through the examples that follow below.)

— Media example #6: BBC: ‘Record number of prosecutions for violence against women’

An activist quoted in the article asserts:

“This progress must continue until we have a system where women who experience domestic violence have exactly the same level of confidence as victims of other crimes, that they are heard and believed, the system works for them and protects their human right to live free from violence.”

((Thought-experiment #6.1: Is “record number of prosecutions” a valid or useful indicator of “progress” – and if so, ‘progress’ for whom? In exploring this, consider factors such as Simon Guilfoyle’s warnings on valid and invalid metrics and arbitrary numeric targets, or the potential risks of the Shirky Principle, that “Institutions will try to preserve the problem to which they are the solution”.))

((Thought-experiment #6.2: In the diagnostic we noted that “It’s my right!” is a key-phrase commonly associated with the probable presence of power-against – specifically, in this case, power-against as abuse, ‘offloading responsibility onto the Other without their engagement and consent’. To what extent does the quote above imply that, for the purported victim, the responsibility for “protects their human right to live free from violence” can be ‘exported’ exclusively to others as a Somebody Else’s Problem? What would be the implications of this? – in particular, to the victim’s access to ‘power-from-within’, self-empowerment and self-responsibility?))

((Thought-experiment #6.3: In thought-experiment #5.2 †, we explored the implications of arbitrarily isolating-out DV in general from the broader societal-wide continuum of abuse and violence. In this example, “violence against women” has been further isolated-out from the broader context of DV, exploring only the subset of DV in which women alone are identified as ‘victims’. As before, what are the advantages and disadvantages of isolating out that one specific sub-segment? Which stakeholders within the overall context – if any – would benefit from such an arbitrary separating-out? What are the risks here of an arbitrary ‘anything-centrism’ that actively excludes all other views or perspectives than its own?))

((Thought-experiment #6.4: Apply language-inversion to the quote above, such that men rather than women are arbitrarily singled out for special concern: “This progress must continue until we have a system where men who experience domestic violence have exactly the same level of confidence as victims of other crimes, that they are heard and believed, the system works for them and protects their human right to live free from violence”. Given that from item #2 † we know that both men and women may be victims of DV, and in roughly similar numbers, that revised assertion should be equally valid: yet what is your response? What would you expect any difference in societal response to be? What assumptions and stereotypes would underpin such differences in response?))

((Thought-experiment #6.5: Revisit thought-experiment #5.5 † above, again with a symmetric comparison of the current context of systemic support for women and men as victims of DV. Could either or both “have exactly the same level of confidence as victims of other crimes”? Would either or both experience “that they are heard and believed”? Would either or both feel and experience that “the system works for them and protects their human right to live free from violence”? If there seem to be differences in support-systems and service-provision between those provided for women or for men, what assumptions, social-stereotypes and ‘policy-based evidence’ might underpin those differences? What disservices might arise from such differences? And what, perhaps, could be done to improve the system such that it delivers better services overall?))

— Media example #7: BBC: ‘Scalded husband: ‘No shame’ for male domestic abuse victims‘

A common assertion in DV models such as Duluth is that all male injuries – if any occur at all – arise as the result of self-defence by the woman.

((Thought-experiment #7.1: It’s possible that all abuse and violence, from anyone to anyone, arises from childish ego-defence – yet to what extent, if at all, would it be valid to describe ego-defence as self-defence? If there are fundamental differences between ego-defence and self-defence – particularly in terms of self-responsibility and suchlike – then what are the probable implications if such distinctions are arbitrarily blurred? What are the implications if category-F ‘Priority and privilege’ is applied, such that the ‘right’ for ego-defence to be classed as ‘self-defence’ is assigned to some parties but not others?))

This item provides a clear example of category-A ‘Physical-assault’ / category-B ‘Use of weapon’ violence by a woman, in which ego-defence might possibly apply, but self-defence explicitly does not:

[His partner] Gilbertson went to make a cup of tea but returned with a jug of boiling water which she poured over his head from behind.

Peterborough Crown Court heard she said “there you go”, as she tipped it over her husband.

Although his injuries were not life-threatening as such, they could easily have been so, and were severe enough to require extensive hospital treatment. The burns resulted in permanent scarring all over his head and over much of his upper-body:

The report continues:

The attack, he said, was the culmination of escalating verbal abuse. He had also needed hospital treatment a few weeks earlier after Gilbertson threw hot tea over him as he slept.

This point about escalation is one of the key reasons why allowing power-against to continue unchecked is so dangerous, and why support-systems need to mitigate urgently against any of the respective warning-signs. Because power-against doesn’t satisfy the actual underlying need, but instead gives a delusory feeling of ‘control’ over the Other that quickly fades away, it can be highly addictive. Hence it can spiral very quickly from – in this case – mild power-under category-K ‘Denying and blaming’, to more-serious power-over category-D ‘Emotional abuse’, to near-lethal category-A/B ‘Assault with weapon’. This can occur in any power-against context, from intra-individual (e.g. self-harm), to one-way or two-way interpersonal (as in this case), to multi-way (e.g. familial ‘mess’, workplace-bullying, or dysfunctional-organisation ‘hazing’ culture), to sub-cultural or whole-culture (e.g. gang-feud, rioting or full-on civil-war).

(Some people are surprised to see ‘hot tea’ or ‘jug of boiling water’ classed as weapons, but such ‘domestic weapons’ are actually the ones most often encountered in DV and the like. A weapon of some kind has always been a means by which those who perceive themselves to be ‘powerless’ can ‘level the playing-field’ between themselves and those they perceive to be ‘powerful’. The problem, though, is that perception and reality may be a long way apart…)

Mr Gregory said he agreed to speak about the abuse, and show his scars, to address the stigma surrounding male victims of domestic violence.

“As a man who is a bit older and who isn’t exactly small, there is a perception that you can’t be a victim of domestic violence. But it should be the same message that they put out for women – don’t be frightened, you don’t have to put up with it.”

((Thought-experiment #7.3: Revisit #5.5 †, specifically the section where “someone in the office who’s upset” is a man. Given this example, what would be the indications or symptoms of any “stigma surrounding male victims of domestic violence”? What would be the likely impacts of any such “stigma” of ‘shame’ or the like, in terms of identification of reporting on DV, or provision of support-services? What disservices might be caused by any such “stigma”? In what ways – if any – is such a “stigma” around DV any different for men or for women? Is there any difference in presence or impacts of such a “stigma”, for men, or for women? If so, what cultural assumptions, stereotypes, and/or ideologically-driven echo-chambers underpin those differences?))

((Thought-experiment #7.4: When some form of ‘anything-centrism’ is in force, there is a strong tendency to reject any counter-examples that clash with the assumptions of the respective echo-chamber – usually by asserting that the counter-example is irrelevant relative to the ‘self-evident truth’ of that specific something-centrism, and demanding that attention be returned to the ‘proper’ centre. For example, some people respond to a case such as this example, by saying that this case doesn’t count, that it’s “the exception that proves the rule”, and that DV is exclusively male violence against women and hence that the woman’s actions ‘must’ have been in self-defence. Revisit #6.3 with this case in mind, to explore more about how an echo-chamber’s ‘policy-based evidence’ loop can operate in real-world practice, and how it impacts in contexts of this type.))

— Media example #8: BBC: ‘Male domestic abuse victim: men are scared to come forward‘

Another counter-example to the Duluth-type model of DV, in which the woman’s category-A/B ‘Assault with weapon’ caused life-threatening injuries to the man:

Mark Kirkpatrick was found on a street in Lancashire seven months ago after his former partner Gemma Hollings attacked him with a pole, hammer and a glass bottle. …

When police found him they said he was so traumatised he did not realise how badly injured he was. They said he could have died.

The article again describes another all-too-typical escalation of power-against, from category-D ‘Emotional-abuse’ and category-G ‘Isolation’, to category-B ‘Intimidation’ and category-C ‘Economic abuse’, all the way to near-lethal category-A assault. The image from the article gives some indication of the more visible injuries:

The article continues:

He lied to the officers about what had happened and said he avoided speaking to them about the violence he was suffering.

“In a way I was worried about coming forward, about it getting out, what people would think ‘Oh he’s been beaten up by a woman’.”

In the end he told the police what was happening.

Mark says: “Men are probably scared to come forward because they’re scared what people will think.”

“He lied to the police” is technically category-L ‘Lying’, much as we saw in item #4c † – but the motivation in this case is different, as a protection against expected category-D ‘Emotional abuse’ from others, rather than for category-J ‘Third-party abuse’ against others. “Scared of what people will think” is, again, defensive against expected emotional-abuse, third-party abuse and more.

((Thought-experiment #8.1: Revisit #5.5 †, and consider a variation of that scenario in which the respective woman or man is holding back or even lying, to protect the partner and/or “Scared of what people will think” of the partner or themselves. What difference would this make to what happens in that scenario? What questions would you need to ask, and in what way, so as to elicit the truth of what’s actually going on for that person?))

Looking back Mark explains why he didn’t defend himself. “I get asked that question a lot. Why didn’t I hit her back? I just didn’t. I don’t hit girls. I’m not like that.”

((Thought-experiment #8.2: Many boys and men report having received strong cultural-conditioning about “You don’t hit girls, ever, even if they hit you”; very few girls report having had the equivalent conditioning around “You don’t hit boys” – or against hitting other girls, for that matter. What difference might this make to the respective gender’s perception of the culpability for physical-violence done by them, versus to them, even when the respective actions are the same? Might this lead, for example, to a situation in which females believe that that they entitled to hit males, but the inverse is never allowed? What impact might this have on males’ ability to defend themselves in the face of serious assault – as in this case – and on social perceptions of responsibility and culpability as a result of such self-defence?))

“You don’t hear it that often of men but they shouldn’t have to suffer. No one should – men or women.”

((Thought-experiment #8.3: “They shouldn’t have to suffer. No one should – men or women.” That equality-oriented perspective above contrasts with the Duluth Model, which, as we saw earlier, asserts that only women – and, potentially, children – are ever victims of DV, that men are only ever the perpetrators, and that “men are perpetrators who are violent because they have been socialized in a patriarchy that condones male violence, and that women are victims who are violent only in self-defense”. Revisit #0.3 ‡ to reassess your own perspective on Duluth and similar models: do you still hold the same views as then as to its validity and its strongly gender-oriented approach to DV-mitigation? If not, what has changed for you? Why? And if any change did take place, how did that change occur? – what were the triggers for change?))

— Example #9: Wikipedia: Duluth Model: Effectiveness and criticism

The Wikipedia page on Duluth Model notes that “As of 2006, the Duluth Model is the most common batterer intervention program used in the United States.” It is also used in several other countries, including the UK and Australia. Its use is often mandated by law, and attendance on a Duluth programme required as part of court-sentencing for purported DV by males.

Yet how effective is it in practice? Does it actually assist in reducing recurrence of DV? The studies referenced in the Wikipedia article seem to suggest not:

A 2003 study conducted by the U.S. National Institute of Justice found the Duluth Model to have “little or no effect.”

A 2011 review of the effectiveness of batterers intervention programs (BIP) (primarily Duluth Model) found that “there is no solid empirical evidence for either the effectiveness or relative superiority of any of the current group interventions,” and that “the more rigorous the methodology of evaluation studies, the less encouraging their findings.” That is, as BIPs in general, and Duluth Model programs in particular are subject to increasingly rigorous review, their success rate approaches zero.

((Thought-experiment #9.1: What would your response be if you’re told by others, who use different models and methodologies than your own, that the usage of your models and methods has “little or no effect”, and that “when subject to increasingly rigorous view, their success rate approaches zero”? To what extent would you defend your models and their underlying assumptions? To what extent would you assume that those others are caught up in an echo-chamber of their own, their critiques of your work relying on ‘policy-based evidence’? At what point would you assess those critiques on their own terms rather than solely on yours?))

We might note that if a service’s “success rate approaches zero”, then by definition it is at best providing a non-service, probably a misservice, and arguably even a disservice, at least as a waste of everyone’s time and money – a form of category-C ‘Economic abuse’ of all stakeholders in the context (other than perhaps of those receiving payment for delivering such ‘services’). But the critiques in the article suggest that the potential for Duluth to deliver disservices may extend considerably further:

Criticism of the Duluth Model has centered on the program’s insistence that men are perpetrators who are violent because they have been socialized in a patriarchy that condones male violence, and that women are victims who are violent only in self-defense.

((Thought-experiment #9.2: What’s clear here is that the critiques and counter-critiques are founded in a Kuhnian-style paradigm-clash – in particular between those who view interpersonal violence primarily in ‘top-down’ political terms, more in terms of the collective, drawing on a Marxist-style concept of power-relationships within ‘the patriarchy’, versus those who view it more ‘bottom-up’, more in terms of individuals and their histories, drawing on concepts more from the domain of therapy. Each of these paradigms sees the world in fundamentally-different ways, deriving their own ‘policy-based evidence’ that may often be inherently incompatible with other paradigms. How would you resolve such a paradigm-clash? And, given George Box’s aphorism that ‘all models are wrong but some are useful‘, how would you identify which aspects – if any – of any given model would be useful within any given context?))

The ‘Criticism’ section in the article includes a 1999 retrospective on real-world application of the Duluth Model by Ellen Pence, one of the model’s two co-authors:

By determining that the need or desire for power was the motivating force behind battering, we created a conceptual framework that, in fact, did not fit the lived experience of many of the men and women we were working with. The DAIP [Duluth Abuse Intervention Program] staff […] remained undaunted by the difference in our theory and the actual experiences of those we were working with. […]

It was the cases themselves that created the chink in each of our theoretical suits of armor. Speaking for myself, I found that many of the men I interviewed did not seem to articulate a desire for power over their partner. Although I relentlessly took every opportunity to point out to men in the groups that they were so motivated and merely in denial, the fact that few men ever articulated such a desire went unnoticed by me and many of my coworkers.

Eventually, we realized that we were finding what we had already predetermined to find.

“The staff remained undaunted by the difference in our theory and the actual experiences of those we were working with” – and all counter-evidence not just “unnoticed by me and many of my coworkers” but actively blocked from view, dismissed as others being “merely in denial”. It’s a near-perfect description of a Gooch’s Paradox failure – a self-referential echo-chamber running almost entirely on predefined beliefs and ‘policy-based evidence’:

Yet notice that Pence and her colleagues did find a way to break free from that loop: “It was the cases themselves that created the chink in each of our theoretical suits of armor”, such that “Eventually, we realized that we were finding what we had already predetermined to find.” Although an echo-chamber may run almost entirely on predefined beliefs and ‘policy-based evidence’, the keyword there is ‘almost‘ – and in my experience at least, and as illustrated in Pence’s description, there will always be some way, some ‘chink in the theoretical armor’, via which the crucial real-world evidence can reach through into our awareness enough to disrupt the loop. The hard part, often, is in finding the inner strength and courage to keep those chinks of awareness open… – though there are distinct disciplines that can help in doing so.

((Thought-experiment #9.3: Pence’s example above illustrates a group caught up in their own echo-chamber loop, and then eventually finding a way to break free. In what ways do you risk getting up in an echo-chamber loop, about some aspect of your own work? What is the respective “suit of theoretical armor” that you’d build so as to protect that loop, and why would you build it? What ‘chinks in the armour’ would need to exist for you to break free, and see the world more as it is rather than as you expect it to be?))

The worrying part of Pence’s description is in what it implies about the sheer scale of structural abuses that could be imposed and inflicted by the model itself onto those on the receiving-end of its arbitrarily-selected and – according to Pence herself – seemingly-invalid assumptions. If the extent of misdesign is as severe as Pence implies that it is, then those abuses would seem to include:

- blame of men, solely because they were men – category-K ‘Blaming’

- rejection of the men’s experience, particularly as victims of abuse themselves – category-K ‘Minimising and denying’

- “relentlessly took every opportunity to point out to men that they … were in denial”, when in fact they were not – category-D ‘Emotional abuse’

- enforced ‘political re-education’ – category-D ‘Emotional abuse’ and category-F ‘Priority and privilege: Being the one to define gender-roles’

- making payment of benefits etc contingent on completing the program to the facilitators’ satisfaction – category-C ‘Economic abuse’, category-B ‘Intimidation’ and category-F ‘Priority and privilege’

- making continued relationship with children contingent on completing the program to facilitators’ satisfaction – category-B ‘Intimidation’, category-H ‘Misusing children’, category-G ‘Isolation’ and category-F ‘Priority and privilege’

- using the legal-system to impose all of these forms of abuse on others – category-J ‘Third-party abuse’

And also:

- facilitators receiving payment and more for delivery of these disservices – category-C ‘Economic abuse’ of the state, taxpayers and others

Even more worrying is that, despite Pence’s own critique above being published back in 1999, and other fundamental critiques being published both before and since, the model has continued to be adopted even further throughout the world, seemingly without any rigorous review at all. An excess of misplaced zeal by a small group of activists is understandable, if never excusable as such; but a failure of social-policy on this kind of scale, that would have severe life-damaging impacts on literally millions of lives, would be both incomprehensible and unforgivable. If Pence’s assessment of the model’s inherent invalidity in most real-world cases is correct, then the abuses imposed would probably include:

- cases such as in #7 and #8 above subjected to false arrest and false charges as ‘the perpetrator’, solely because they’re male

- systematic denial of female agency in DV etc, and, for women only, removal of counter-perjury checks-and-balances, enabling extensive use of false-allegations and other forms of third-party abuse

- systemic allocation of support-resources reserved for women only, with men actively excluded from needed support-resources

- broad-scale social-policy on DV and other themes built entirely around male-blame, creating a literal terrorism against men, their children, and ultimately women also

- economic-abuse, isolation-abuse and misuse of children such as skewed property-division and ‘custody’ of children

- court-system, welfare-system, benefits-system and social-services system all set up to inflict third-party abuse, primarily on men, but secondarily on children and women also

- (and more, and more, and more: it’s a very long list…)

(I won’t bother cataloguing the specific abuse-categories for each of these impacts: you can map it out yourself, via web-searches and the like for the respective real-world evidence, but essentially it comes down to various forms of every category of violence and abuse.)

If that is the case, then that would be about as deep into disservices as it’s possible to get. Given that the nominal purpose of the model is to reduce abuse and violence in the community, that would not be a good outcome…

((Thought-experiment #9.3: Note that the above applies to any type of serious misframe: in the DV context, for example, similar types of abuses would also occur for a misframing that was the other way round, a symmetric power-model imposed on a context in which an asymmetric model more closely matched the real-world needs. Given that everyone suffers to some extent from cognitive-bias – that everyone has their own echo-chambers – then what can we each do to mitigate the impacts and effects resultant from each potential yet seemingly-inevitable misframe? For example, within each context, what forms of diversity would we need, with a broad enough range of perspectives to disrupt a potential ‘policy-based evidence’ loop? From where do we find the courage to allow discordant voices to cut across our complacencies, and invite, rather than silence, constructive dissent? None of this is easy: but if disservices are to be avoided, this kind of self-challenge must be done…))

— A final note:

((Thought-experiment #10.1: Revisit #0.1 ‡ to reassess your views in the light of the examples and thought-experiments here: how much, and in what ways – if at all – has your perspective of the DV context changed whilst working through all of the examples and thought-experiments above? What have you learnt about how echo-chambers and their underlying ‘policy-based evidence’ loops work in real-world practice, and about what kinds of questions and modes of enquiry would be needed to test and – if necessary – to counter and resolve them?))

(Continues in Part 5D: ‘Services and disservices – 5D: Social example (Implications for EA)‘.)

Leave a Reply