What I do, and why

“Are you the guy who writes books?”, asks the young woman behind me in the cafe.

Well, yes, I am – but much as for her, it’s taken me a moment or two to recognise her, and then remember the context in which we last spoke, a couple of weeks back. A nice memory.

I’ve no idea how that initial conversation had started – they just seem to happen, somehow – but it had soon shifted to writing. It had become clear, quite quickly, that she herself wanted to write, but had no idea where to get started, or how.

What kind of writing did she like, I’d asked. Which authors? Stephen King, she’d said. So look at the way Stephen King structures his stories; how his characters develop, what challenges they face. Look inside, too, to explore how it feels to be each of the characters – their drivers, the fears they each face within themselves. For every aspect of the story, observe, orient, decide, act. All of it iteratively, recursively – each person’s story weaving through each of the others’, creating a shared tapestry of meaning and desire and denouement. Simple as that, really.

And where to start? One example: just look around the town – again, simple as that. This an old town here, with more than two thousand years of history in every small locale, layer upon layer, literally under our feet, everywhere around us. So just pick somewhere to start: anywhere would do – anywhere at all, any place that seems to announce itself, say ‘Hello’ in its own strange way. Or, as Robert Pirsig once advised one of his students, choose a building, start with the top-left brick, and build outward from there.

We’d talked for a while, and then she’d had to go out on an errand for the cafe. I’d had to leave too, soon after, so I’d left a £5 note with her friend, to pay towards getting her a good notebook from the Paperchase store around the corner: make it special, get her started, provide that bit of extra motivation.

It worked.

When we met at the cafe again, as above, she was almost wildly excited. She’d gotten started, all right. Written her first short-story; then another, and another. Her friends liked what she’d written, the right Stephen King-like frisson of fear. No doubt, there’d be some years of hard work ahead of her, to make it work as well as she really wanted – but she now had the momentum to do it, and the motivation too. A real sense of aliveness in her, that hadn’t been there before. Literally changing her life, for the better – and all of it started up through just one brief conversation.

I live for moments like that…

And creating conditions under which those moments can happen – not just for individuals, but for organisations too – is what I do, and why I do it.

Yet describing what I do, and how I do it – and exactly how it delivers its very real value – well, that’s where it gets hard… A constant search, throughout too many years now, to find a good way to reframe the way that I work, in a form that actually makes sense for anyone else…

There’s structure to it – but it’s not the usual kind of structure that most people seem to expect in this type of work.

There’s a distinct process to it – but it’s often not a linear step-by-step process, in the usual sense. Yes, there are step-by-step elements in it, and to it – but the overall process is almost anything but linear in nature.

The answers we need do arise in the process – but it’s not about ‘answers’ as such. Indeed, often its most important attribute is that it helps people find the right questions – the ones they didn’t know about, the ones that they most needed to find for themselves.

It’s sort-of predictable – but only in the sense that it does lead to real outcomes, as above. The catch is that often we won’t and can’t know beforehand exactly what each outcome will be. In effect, it’s dominated by the three-part ‘Enterprise-Architects’ Mantra‘, of ‘I don’t know‘, ‘It depends‘ and ‘Just enough detail‘ – which means that uncertainty and suchlike will be an inherent part of the story even before we start.

And whilst it does indeed solve real business-problems and the like, it’s not a ‘solution’ as such – at least, not in the sense so beloved by the big–consultancies and their ilk. In some ways it’s not even about ‘problems’, either – instead, it’s more about making sense in and of a context-space, within which that dichotomy between ‘problem’ and ‘solution’ is itself one of the key barriers against making sense.

All of which not only makes it hard to explain, but kinda hard to teach, too…

The real core of it, perhaps, is about skills – about what skills are, why we need them, what happens in skills-development, and how development of skill is inherently different from training. I probably started serious work on it in my mid-teens, some fifty years ago, but my first formal writing on it was published forty years ago this year, in my Masters thesis at London’s Royal College of Art, on ‘Design for the education of experience’.

(My somewhat-extreme test-case for that research-thesis was a self-teaching guide for the then supposedly-‘unteachable’ skill of dowsing. But the published version of that book went on to become something of a bestseller: overall, it’s sold something like a quarter of a million copies, in about ten different languages, and has never been out of print in the four decades since it was first published. Which kinda proves that there might be some value in the theory of skills behind it?)

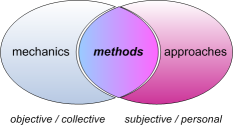

As summarised in the post ‘Methods, mechanics, approaches‘, the crucial distinction between training and skills is in how they view the role of methods, the means via which action is taken and guided towards some desired outcome:

— In training, methods are assumed to be context-independent, and that each method will lead always to the same outcomes, regardless of who or what applies that method. Because of this, everyone is taught the same method. (For computer-based machines, such training is typically termed ‘programming’.) In effect, method is the sole centre of focus, with context either ignored or deemed irrelevant.

— In skills-based work, methods are assumed to be somewhat context-dependent, and that use of the same methods in different contexts may or will lead to different outcomes. Which means that different methods will likely need to be applied, dependent on the context – human or otherwise – in order to achieve the equivalent outcome. Which means, in turn, that we can’t just teach the same method in each case, because it may well work only with one person in one context – and that agents that cannot adapt to context, such as many if not most current computer-based technologies, cannot be relied upon to deliver the desired outcomes. In effect, the appropriate method to use in each context arises from a context-specific mix of ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ factors – respectively the ‘mechanics’ and ‘approaches’ in the context – and hence the key focus needs to be on those factors, rather than on specific methods that arise from them.

In training, we push the predefined methods in to someone or something, almost literally forcing them onto the same track of action, mindset and more. And because training is method-centric, the methods, by definition, are always ‘right’ – and anyone or anything that does not achieve the desired outcome from that training is presumed to be ‘wrong’ or ‘at fault’.

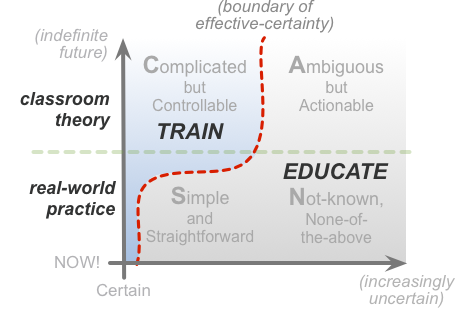

For skills, we lead the appropriate methods out from someone or something: education in its literal sense of ‘out-leading’. Ultimately, for skills-based methods, there’s no such thing as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ – just ‘better’ or ‘worse’ in terms of reaching towards desired-outcomes. And, crucially, working with the real-world takes priority over any predefined ‘the method’…

No doubt training is always the ‘easiest’-seeming option – and certainly the cheapest, which is one reason why it’s so popular. But the reality is that, in the real-world, context is king – which is a key reason why training tends to work better in theory than it does in real-world practice. In SCAN terms, the distinction looks somewhat like this:

In practice, and particularly so in a whole-context field such as enterprise-architecture, we’ll need to cover the whole of the context-space – not merely the easy bit that can be addressed by training…

Yet as my old friend Geraldine Beskin, at Atlantis Bookshop in London, pointed out to me the other day, there’s another entire dimension to this, about purpose, about desire – about what we want to do, rather than merely what we can do. In other words, drivers that seem, or are, somehow ‘greater than self’. Linked to that are concerns such as competence – that the methods we use will change according to our experience and maturity within that skill. And, moving more to the ‘mechanics’ side of the equation, there are other ‘external’ elements such as inherent-uncertainty and ‘variety-weather‘ – the ways in which the set of factors that define the variety of a context are themselves subject to variety.

So the methods we need in each context will depend not just on ‘objective’-mechanics and ‘subjective’-approaches, but on these broader ‘external’ drivers too:

In effect, that skills-model is the core of my work: everything extends outward from there. Tools like SCAN and SCORE and Enterprise Canvas; the overall approach of context-space mapping and suchlike; they all represent different ways of tackling the same core issues, about sensemaking, decision-making, action and review. In that sense, there’s a solid consistency of metastructure and metatheory that underpins all of it.

The catch, of course, is that it doesn’t conform with the mainstream expectations set up by the big-consultancies and training-organisations and the like – in fact, much of it is almost exactly opposite to those expectations:

— Emphasis:

- mainstream approach: focus on repeatable training for repeatable methods in repeatable contexts

- my approach: focus on individual-oriented understanding and skills to elicit context-specific methods for use in often either partially or wholly non-repeatable contexts

— Order versus unorder (SCAN: Simple / Complicated versus Ambiguous / Not-known):

- mainstream approach: focus on order and ‘control’, and avoid, ignore or dismiss the existence of unorder in the context

- my approach: always address order and unorder together, within the context as a unified whole

— View of context-space:

- mainstream approach: partition into ‘problem’ and ‘solution’, then provide prepackaged ‘solutions’ for preselected ‘problems’

- my approach: keep partitioning to a practical minimum, and work with client to assist context-specific solutions (or, for ‘wicked-problems‘, metamethods for dynamic ‘re-solution’) to emerge from the context

— Authority:

- mainstream approach: the client has the need and the questions – the role of the consultancy is to provide the expertise and the answers

- my approach: the client has the expertise and the answers, though often without conscious awareness of such – the role of the consultancy is to guide the questions that will elicit that knowledge, according to context-specific need

It’s true that the mainstream methods do work, if everything in the context-space is entirely predictable, and always amenable to prepackaged ‘solutions’. Which, however, is a big ‘if’ in many (most?) present-day real-world contexts…

Hence the reason that I take the approach that I do: it’s because it’s the only way that works in all aspects of all contexts – rather than that work only in certain arbitrarily-selected subsets of some types of context, and don’t work well with anything else.

(Or, worse, that only work in certain contexts but pretend to work in other contexts where they actually don’t and can’t – such as in the IT-centric term-hijack of the ‘enterprise-architecture’ term, and similar screw-ups-for-everyone-involved…)

And given the amount of effort that goes into getting things to work properly, and well – that “things work better when they work together, on purpose”, and suchlike – I’d much rather that that effort went into something that actually worked!

So that’s what I do, and why I do it. Makes sense, I hope?

If not, let me know, perhaps? Over to you for comment and suchlike, anyway.

Thanks for the insight into “the why”!

This is a useful post for someone who’s just had an engagement with Tom, helping me to step back and reflect on what’s just been done. I think our small team had tacit expectations of what training or consultancy would be, and though Tom talked through the Venn diagram early on, I’m only now able to understand its significance. Also, overcoming those expectations and getting to the point where we started generating useful outputs in just a few days itself represented a rapid pass through the storming-norming-performing steps that fit to Tom’s wider five-phase model.

Learning about and working through Tom’s enterprise canvas and other approaches was different from standard training, and suited my journeyman role. However, I still struggled to absorb these as mechanisms and fit them to things learnt as an apprentice (e.g. data flow diagrams, UML, the TOGAF ADM). Maybe these are professional equivalents of a mother tongue, giving us the cognitive structures or schema that we have to use to think.

Anyway, I hope Tom realises he achieved his purpose as stated here with our team, kindling that impetus to buy a new notebook and get the ideas for our novel down. We are now better able to work consistently and productively in an ambiguous or not-known “it depends” space.

Thanks!

Many thanks for this, Joe – hugely appreciated! And thanks also for the sessions with you and your colleagues: I learnt a lot, as I always hope to do. We’ll keep in touch, anyway.